The Economist, May 16th 2015

Original Here: Reforming Cuba: Be More Libre

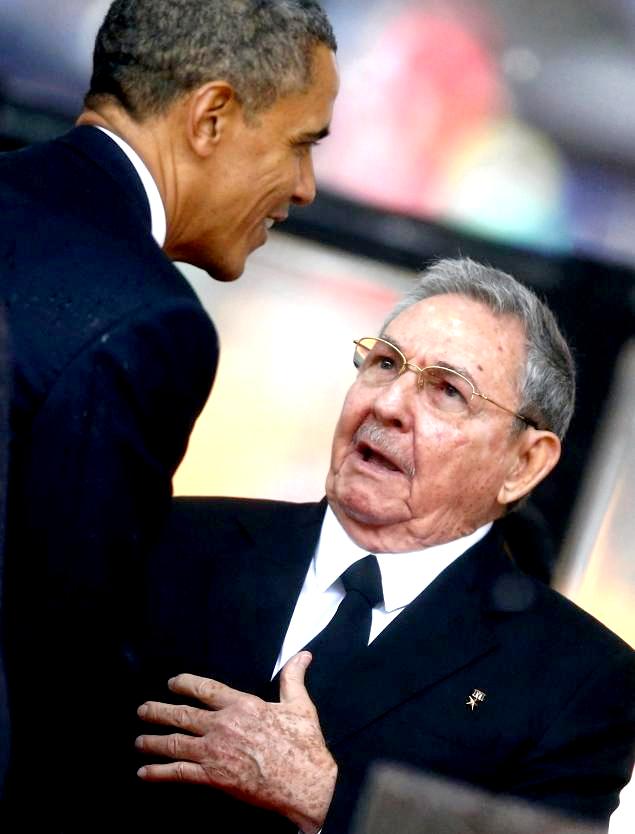

IT HAS been five months since Cuba and the United States announced that they would end their long cold war, but Cuba’s president, Raúl Castro, is still basking in the afterglow. On his way home from Russia this week he stopped off at the Vatican to see the pope, and said he might return to the Catholic faith. Later François Hollande paid the first-ever visit to Cuba by a French president; he was granted an audience with Fidel Castro, Raúl’s ailing brother, who led the revolution in 1959 and ruled until 2008.

But beneath the bonhomie lies unease. Cuba’s creaky revolutionaries spent half a century blaming the American embargo for all the island’s woes. Now they resist American capitalism for fear of being overrun. The result for most ordinary Cubans is not too much change but too little (see article). The island is poorer than many of its neighbours. Doctors earn just $60 a month—after a 150% pay rise. Food and other basics are in short supply. Boat people still flee to Florida’s shores.

Cuba deserves a proper democracy and a robust market-based economy. Sadly, that is unlikely to happen soon. Some things are changing. Private guesthouses, restaurants, barber shops and the like have begun to flourish, creating the kernel of an entrepreneurial middle class. But if Cubans are to benefit from the opening with America, their rulers need to reform more boldly and quickly than they have done so far.

A cocktail of reform

Where to start? Cuba should begin by opening up many more sectors to private enterprise. Currently, Cubans can be “self-employed” in 201 activities (including reading Tarot cards), but few that require a university degree. In place of a “positive list” of permitted private activities, the government should publish a negative one that reserves just a few for the state. All others would then be open to private initiative, including professions such as architecture, medicine, education and the law. The new bourgeois are potential customers for professional services; catering to that demand would in turn expand the middle class.

Liberalisation is urgent in wholesale markets. Today enterprises such as restaurants are forced to buy supplies from state-run supermarkets where ordinary people shop, which exacerbates shortages. This undermines popular support for the emerging private sector.

The climate for foreign investment must also improve. Cuba woos foreign investors for the expertise, jobs and currency they bring, but treats them shabbily. Under a supposedly friendly new law, they must still recruit workers through state agencies, to which they pay hard currency; the agencies then pay out miserly salaries in pesos. Imported inputs pass through bureaucratic state-run enterprises. Worst of all, legal codes are vague and their application is arbitrary. In recent years several foreign businessmen have been imprisoned (and later released) with little explanation.

How much of this thicket Mr Castro is prepared to clear away is uncertain. The party’s leadership has hinted that its congress would strengthen the National Assembly, a rubber-stamp body. A proper legislature that could write laws would give security to enterprise. Cuba is also bracing for a painful currency unification, which will end a huge subsidy to state companies.

For many of the revolution’s ageing leaders reform and privatisation are yanqui-inspired dirty words. The regime looks to China and Vietnam, where communist governments have embraced capitalism without yielding power. The Cuban communists are wary: they fear that, if they give up too much economic control, they will be obliterated just like the communists of eastern Europe. Yet the bigger risk would be merely to tinker with a system that keeps Cubans poor at a time when their aspirations are rising.

A Symbol of Santeria, the meaning of which I do not understand.

A Symbol of Santeria, the meaning of which I do not understand.

Not entirely relevant to this Economist editorial. Photo taken in April 2015 on Calle Animas