BY SAMUEL FARBER, June 10, 2015

Original Essay from “JACOBIN” Here: Cuba’s Challenge

Samuel Farber was born and raised in Cuba. He is the author of Cuba Since the Revolution of 1959: A Critical Assessment.

When in the 1950s, along with many of my high school classmates, I became involved in the struggle against Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista, one of our teachers remarked that we had no real reason to criticize the state of our country because so many other nations in the region — such as Bolivia and Haiti — were much worse off than us.

His description of Cuba’s comparative position was accurate, but incomplete. On the eve of the 1959 Revolution, Cuba had the fourth highest per capita income in Latin America, after Venezuela, Uruguay, and Argentina.

And although average per capita income is an insufficient, and sometimes misleading, indicator of general economic development, other indicators support his picture of the pre-revolutionary Cuban economy: in 1953, Cuba also ranked fourth in Latin America according to an average of twelve indexes covering such items as percentage of labor force employed in mining, manufacturing, and construction, percentage of literate persons, per capita electric power, newsprint, and caloric food consumption.

Yet, at that time the country’s economy was also suffering from stagnation and the pernicious effects of sugar monoculture, including substantial unemployment (partly caused by the short sugar cane season of three or four months). Most importantly, the national indexes of living standards hid dramatic differences between the urban (57 percent of the population in 1953) and rural areas (43 percent), especially between Havana (21 percent of Cuba’s total population) and the rest of the country. The Cuban countryside was plagued by malnutrition, widespread poverty, poor health, and lack of education.

For my teacher, it seems, the fact that other people were worse off made him more accepting of his own life circumstances. But he was the exception. To the extent that Cubans compared themselves with the people of other countries, they preferred to look up to the much higher standard of living of the United States rather than console themselves by looking down at the greater misery of their Latin American brethren.

As a 1956 report of the United States Bureau of Foreign Commerce put it: “the worker in Cuba . . . has wider horizons than most Latin American workers and expects more out of life in material amenities than many European workers . . . His goal is to reach a standard of living comparable with that of the American worker.”

This underlines the fundamental mistake of assuming instead of ascertaining that comparisons of economic performance have any meaning to the people who live in those economies. Taken to an extreme, this mistake leads to an “objectivist” analysis that stands outside history as it is actually lived by its actors and is likely, as in the case of my high school teacher, to result in a conservative commitment to the existing social order, as opposed to a questioning of, or opposition to, the existing social order and its ruling group.

For those who are affected by it, economic development has a meaning that goes beyond economic data and requires an understanding of popular aspirations and expectations, which are based in part on the existing material reality and in part on past history.

In terms of its material reality, the Cuba of the fifties was on the one hand characterized by uneven modernity, fairly advanced means of communication and transportation — especially the high circulation, by Latin American standards, of newspapers and magazines — and the rapid development of television and radio. On the other hand, there were abysmal living conditions in the Cuban countryside.

As far as its history, the Cuba of the 1950s was still living the effects of the frustrated revolution of 1933, a nationalist revolution against dictatorship with an important anti-imperialist component and the participation of an incipient labor movement, then under Communist leadership.

Although this revolution had achieved some significant reforms equivalent in the Cuban context to Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, it failed to achieve major structural changes in Cuban society, such as real national political and economic independence from US imperialism (beyond the abolition of the Platt Amendment in 1934) or any meaningful agrarian reform and diversification away from the one-crop sugar economy with all it implied in terms of economic instability, large-scale unemployment, and poverty.

These were the economic issues brandished by the Cuban opposition at that time to struggle for more or less radical reforms to the existing order, instead of pondering and celebrating Cuba’s comparative high rank among Latin American economies. Thus Eduardo Chibás, the leader of the reform Ortodoxo Party, of which Fidel Castro was a secondary leader, proposed in 1948 a series of modest reforms to improve the life of the Cuban rural population.

Five years later, after Batista’s coup against the constitutional government, Castro — in his “History Will Absolve Me” speech at his trial for his failed attack against one of Batista’s military installations — proposed a more radical series of measures, including giving property titles to peasants holding up to 165 acres of land, with compensation granted to landlords on the basis of the average income they would have received over a ten-year period. He also added new elements to his reform agenda, such as his radical plan for the employees of all large industrial, mercantile, or mining concerns, including sugar mills, to receive 30 percent of profits.

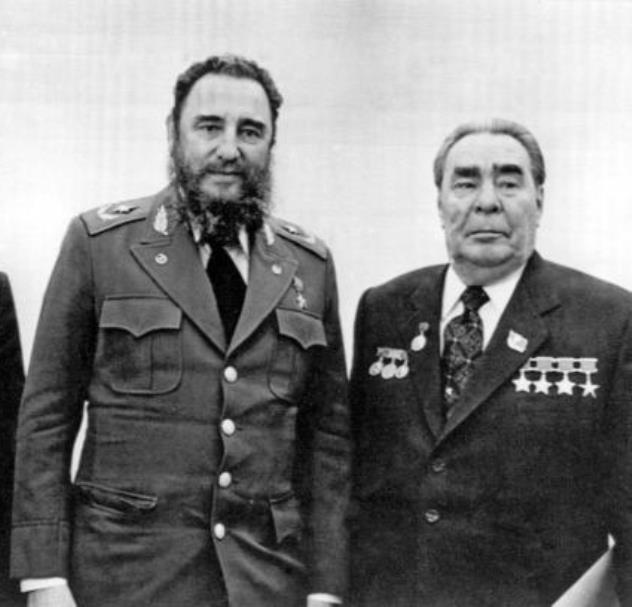

Fidel and Rebels, 1956

After 1959

Immediately after the victory of January 1, 1959, in response to many Cubans’ pent-up expectations, Castro’s revolutionary government engaged in a vigorous policy of redistribution. There was an urban reform law to substantially reduce rents, a left-Keynesian policy of public works to combat unemployment, and a radical, albeit not a collectivist, agrarian reform law proclaimed in May 1959.

Then, in late 1960, in part in response to the hostility of US imperialism and in part based on the political inclinations of the revolutionary leaders, the large majority of both urban and rural property was nationalized by the Cuban state.

In April 1961, Castro declared Cuba to be “socialist,” and it became, in structural and institutional terms, a replica of the model in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. Although Cuba’s one-party state placed more emphasis on popular participation than its equivalents in the Eastern Bloc, its political control was before long just as absolute.

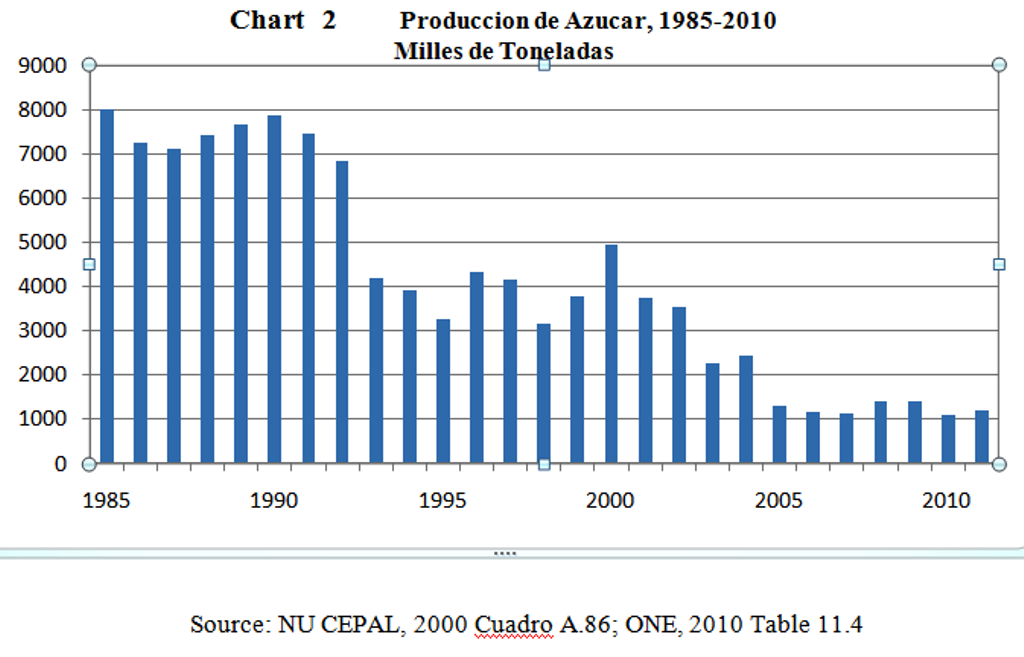

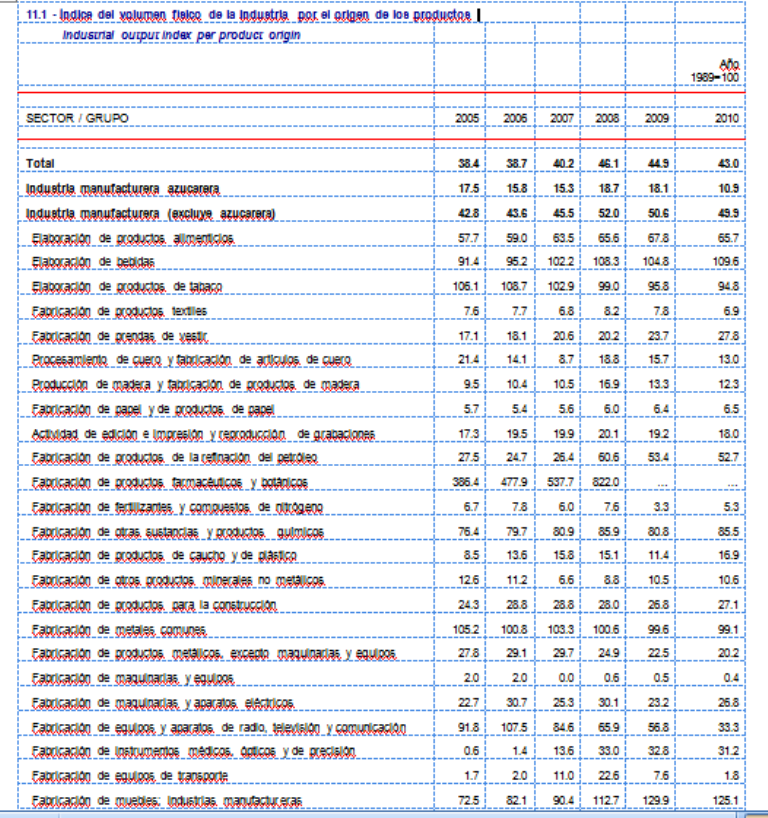

Like the supporters of the Cuban status quo before the revolution, the supporters of today’s Cuban system assert that it is economically superior to other countries, particularly in Latin America. In terms of GDP — which, as previously mentioned, is not by itself a reliable indicator of economic well-being, although the Cuban government relies on it in a modified form — Cuba has fared poorly in comparison with its neighbors.

Whereas in 1950 Cuba ranked tenth in per capita GDP among the forty-seven countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, almost sixty years later, in 2006, it ranked near the bottom of the list, only ahead of Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua, Bolivia, El Salvador, and Paraguay. GDP has increased little since then with a 2 percent average rate of growth in the last five years.

The government’s supporters point to Cuba’s achievements in education and health (in particular, its low infant mortality) as conclusive evidence for its more progressive economic policies. And indeed Cuba has performed very well in the Human Development Index (HDI), which combines income, health, and education statistics.

But while this index does a good job of measuring critical aspects of well-being in the less developed capitalist countries, it does not adequately capture the shape of state-socialist economies such as Cuba. It does not quantify the hardships that people suffer in countries where the economic problems of underdevelopment intersect with those particular to Soviet-style societies.

Take income, for example. Unlike capitalist societies, in Cuba, access to many luxury or high-cost goods is often obtained by the ruling groups through extra-economic, in kind, political means, rather than through the expenditure of monetary income. Although this situation has become more complicated since Raúl Castro took office in 2006 and expanded private economic activity to cover approximately 25 percent of the labor force, obtaining high-end goods still depends to an important degree on political access.

One example is traveling abroad. For the majority of Cubans who don’t have sufficiently wealthy relatives overseas, it is political access to state-sponsored travel — for example, officially sanctioned attendance to political, economic, cultural, or academic conferences — rather than private income that remains the principal way to venture outside the island.

A similar situation exists in terms of Internet access. In Cuba — a country with one of the lowest levels of web availability in Latin America and the Caribbean — many people can connect to the Internet only at their workplace or school, but only for strictly work-related purposes. Otherwise, they run the serious risk of being reprimanded or even losing their ability to go online.

Privately, they can get on the Internet by paying rates unaffordable to average Cubans, and only at tourist hotels or at the centers sponsored by the state telephone monopoly. However, free access to the Internet is the norm for those who are well-situated in terms of political power or have connections to those who do.

Besides the issue of monetary income, the HDI ignores other factors that make living conditions in Cuba difficult. These include the irregular supply and quality of food, housing, toiletries, and birth control devices for women and men. The same applies to the poor state of roads, inter-urban bus and railway transport (premium transportation services exist but are costly and therefore out of the reach of most Cubans), and the delivery of basic necessities such as water, electricity, and garbage collection.

The HDI does not quantify the hardships of daily life associated with these inadequacies either — for example, the amount of time people have to spend going from place to place and standing in line to obtain a wide variety of goods. Economic indexes can also be deceptive insofar as they don’t take into account the maintenance and upkeep of systems that deliver key services.

Take water, for example. Viewed in one way, Cuba ranks well in that regard, with 95 percent of its population officially having access to drinking water. But serious water shortages are a normal condition of life in Cuba. This is partially due to seasonal droughts in certain regions, particularly in the eastern half of the island. But the most important cause of that shortage is the deteriorated infrastructure — broken pipes and numerous leaks — going back to well before the collapse of the Soviet bloc.

For these reasons, more than half of the water pumped by the country’s aqueducts is lost, especially in the Havana metropolitan area. This is much of the daily material reality Cubans face, and it shapes their aspirations and expectations.

Strong Thumbs, No Fingers

The Cuban government and its supporters claim that most of these economic problems are the result of the criminal economic blockade of the island imposed, for more than fifty years, by the United States and which remains mostly in force despite the resumption of diplomatic relations between the two countries.

There is no doubt that the embargo has been damaging, particularly in the early years of the revolution, as Cuba was forced to reorient most of its economic activity towards the Eastern Bloc. Repealing the 1996 Helms-Burton Act and ending the blockade would be a very welcome development for both principled and practical reasons. Such a move would also considerably increase economic activity in Cuba, most likely in the fields of tourism and, possibly, biotechnology and the production and export of certain types of agricultural commodities such as citrus.

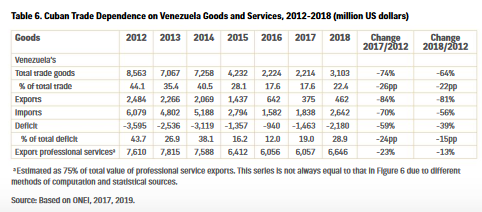

However, the US blockade did not prevent Cuba from trading with industrialized capitalist countries in Asia and Europe, and particularly with Canada and Spain. The principal obstacle to Cuba’s economic relations with those non-US industrial capitalist countries was Cuba’s own lack of goods to sell and thus its lack of hard currency with which to pay for imports, whether capital or consumer goods. Nevertheless, Cuba received more than $6 billion in credits and loans from many of the industrialized capitalist countries until Cuba suspended the service of these debts several years before the collapse of the Soviet bloc.

More important than the damage caused by the US economic blockade is Cuba’s inadequate capital, as well as other problems typical of economically less developed countries — the export of commodities such as nickel and sugar amid unstable world prices — which in turn interact with the myriad economic shortcomings and contradictions of Soviet-style economies, including the failures of agriculture and the scarcity and poor quality of consumer goods.

In truth, Cuba’s achievements and failures resemble those of the Soviet Union, China, and Vietnam before these countries took the capitalist road, suggesting that systemic similarities are more significant than national idiosyncrasies and variations on the general Soviet model.

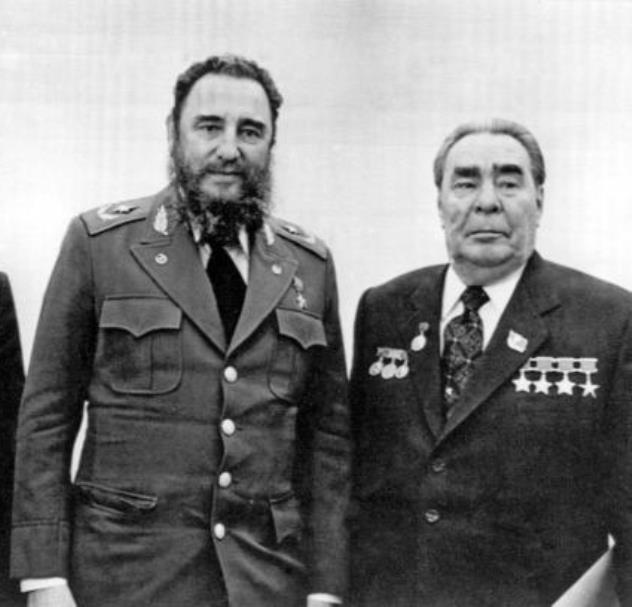

Fidel and Leonid

Fidel and Leonid

Cuba shares with the USSR what the political scientist Charles E. Lindblom called “strong thumbs, no fingers.” Having “strong thumbs” allows the government to mobilize large numbers of people to carry out homogeneous, routinized, and repetitive tasks that require little if any variation, initiative, or improvisation to adapt to specific conditions and unexpected circumstances at the local level — precisely the tasks that require subtle fingers rather than undiscriminating thumbs.

This explains how a Soviet-style government can organize a massive vaccination campaign, while at the same time its bureaucratic, centralized administration and lack of “nimble fingers” prevent it from acquiring the necessary precision for timely coordination of complicated production and distribution in all economic sectors — especially agriculture, among the least homogeneous and predictable areas of the economy.

Cuba’s deficiencies, particularly in the production of consumer goods, also stem to a large extent from its principal leaders’ ideological inclinations. While these leaders have clearly favored the production and delivery of certain collective goods like education and health care, they have tended to be indifferent if not hostile to goods normally consumed by individuals or families.

This is rooted in a deeply ascetic strain of some leftist traditions. The most prominent and consistently austere among the revolutionary leaders was Ernesto “Che” Guevara, who as minister of industry in the early days of the revolution shaped many aspects of the Cuban economy.

When serious shortages of consumer goods began to occur in Cuba in the early 1960s, Guevara spoke critically of the comforts that Cubans had surrounded themselves with in the cities, comforts which he attributed to the way of life to which imperialism had accustomed people, and not to a standard of living resulting from the relative economic development of the country and especially to the working class and popular struggles in the pre-revolutionary era.

Guevara argued that countries such as Cuba should invest completely in production for economic development, and that because Cuba was at war, the revolutionary government had to ensure peoples’ access to food, but that soap and similar goods were non-essential. It is clear however, that his hostility to consumer goods was by no means specific to a war economy.

As he put it in his private reflections shortly after he left the Cuban government in the mid-1960s, “in Cuba, a television set that does not work is a big problem but not in Vietnam where there is no television and they are building socialism.” He added that “the development of consciousness allows for the substitution of the secondary comforts which at a given moment had transformed themselves into part of the individual’s life, with the overall education of society allowing for the return to an earlier era that did not have this need.”

Later, after the failure of the grandiose plans for economic growth that Guevara and other revolutionary leaders articulated, these ascetic politics came to be shared by the entire Cuban government leadership. They were soon consecrated in the Cuban revolutionary ideology as hostility to the “consumer society” of the economically developed world, a view that was never part of the ideology of the pre-revolutionary Cuban left, Communist or otherwise.

It was therefore entirely fitting that during the Cuban economic cycles associated with the spirit and politics of Guevara, the emphasis was always on capital accumulation instead of increased consumption. This was the case, for example, with the Guevarist-type economic period of 1966–1970 (shortly after he left the Cuban government).

As the prominent Cuban economist Carmelo Mesa-Lago points out, at this time the national plan called for a sharp increase in national savings that was to be generated by a cut in consumption through the expansion of rationing, the export of products previously assigned for internal consumption, and the reduction of imports considered unnecessary.

Material incentives sharply decreased, and the population was exhorted to work harder, save more, and accept deprivation with revolutionary spirit. Accordingly, the share of state investment going to the sphere of production increased from 78.7% to 85.8% between 1965 and 1970. This was indeed a Cuban high point of what the Hungarian theorists Ferenc Fehér, Agnes Heller, and György Márkus have called the “dictatorship over needs.”

The Special Period

Until the collapse of the Soviet bloc, the Cuban government was able to deliver for the majority of its people an austere standard of living that, on the whole, guaranteed a minimum of economic security and the satisfaction of basic needs, in spite of serious deficiencies in areas such as housing and consumer goods.

Notwithstanding the serious problems and contradictions of a Soviet-style economy, this was made possible by the USSR’s massive economic subsidies, which helped the Cuban government finance a generous welfare state with an extensive education, health services, and social security system. These massive subsidies were the result of Cuba joining the Soviet state as its junior partner in an international alliance that did confront strategic obstacles in Latin America (because the USSR was reluctant to challenge the US in its own sphere of influence), but that ended up being much more viable and successful in Africa despite some tactical differences.

Although overall literacy was at 76.4% before the revolution, it was much lower in the countryside; the government has succeeded in almost entirely wiping out illiteracy. It has also expanded secondary and higher education, promoting a substantial degree of social mobility facilitated by the massive emigration from the island of its upper class and large segments of its middle classes.

The dramatic enlargement of the military also allowed for the rise into officialdom of many Cubans of humble origin. Black Cubans in particular benefited, with the elimination of the informal but substantial racial segregation that had existed in pre-revolutionary Cuba, especially in the area of employment.

Racism was by no means eliminated. The Cuban government, implicitly identifying racism only with its segregationist form, soon declared the problem solved, with policies of “affirmative action” not even considered, in a context where blacks were not allowed to organize independently to defend their interests.

In general, however, Cuba became a more egalitarian society, attaining in the mid-1980s a Gini coefficient of 0.24 (although this measure also suffers from the political access problems discussed above). It was this, along with the growth of a nationalist and anti-imperialist consciousness that ensured a large base of popular support for the government. At the same time, however, critical voices even inside the Castro administration were systematically suppressed, and political dissidents (as well as petty offenders — Cuba has one of the highest imprisonment rates for common crimes) were jailed in large numbers.

The collapse of the Soviet bloc provoked a massive economic crisis, reflected in the quick and sharp 35 percent GDP drop. Cubans went very hungry in the first half of the nineties, the worst years of the crisis, leading to serious nutritional deficiencies that provoked an outbreak of optical neuropathy in 1991 that affected more than fifty thousand people until it was partially controlled in 1993.

Services such as public transportation went into a tailspin, from which they have only partially recuperated. Inequality has grown significantly, particularly between those with and without access to the hard currency provided by remittances from abroad. Real wages in the public sector, which still accounts for at least 75 percent of the labor force, dropped precipitously, and as late as 2013 they had only reached 27 percent of 1989 levels.

The “Special Period” also had a noticeable impact on the health care system, reducing the gains achieved in the previous thirty years. There are shortages of medical supplies and of family doctors and specialists, who are often working abroad as a part of international programs.

Patients have to even bring their own bedding to the hospitals, and “gratuities” to medical personnel have become increasingly common. Teachers have fled the education field in search of higher wages in other sectors such as tourism; at one point the government even tried to replace those educators with television sets and quickly trained high school graduates, with predictably negative results.

The system of social security, which made great advances in the 1960s with universal coverage and the unification of the previously existing patchwork of pension and retirement plans, went into a sharp crisis as the peso-denominated pensions fell to a fraction of their previous purchasing power.

Most importantly, during the quarter century that has elapsed since the fall of the USSR, the support of the regime has fallen quite substantially, particularly among young people. This does not mean that they have begun to openly oppose the government. They are far more likely to look for individual ways to resolve these problems. They would rather leave the island than politically confront a government that despite having released most political prisoners and allowed for a significant degree of social liberalization (for example, in terms of religion and emigration) still maintains a one-party state and an apparatus of repression. (Although it typically employs close monitoring, harassment, and frequent short-term arrests of dissidents instead of the long prison terms that were the norm under Fidel Castro’s rule.)

The Critique from the Left

Supporters of the government, especially abroad, continue to defend the system as if nothing happened during the last twenty-five years, and keep pointing to poor countries such as Haiti — which were worse off than Cuba before the 1959 Revolution — as evidence of how better off Cuba is. But for the most part, the Cuban people are not comparing their standard of living to those of other less developed countries.

Older Cubans are much more likely to compare their current hardships with the greater security and predictability they experienced before the Special Period, and remember nostalgically the early 1980s when the opening of the farmers’ markets, after the mass exodus from the Port of Mariel in spring 1980, allowed Cubans to reach perhaps their highest living standards since the 1960s.

For many Cubans, and particularly for the disenchanted young who are keenly aware of contemporary cultural trends in fashion, music, and dance, the existence of a large Cuban-American community in South Florida has also become a major standard of comparison.

And the nascent critical left in Cuba — like the oppositionists of the 1940s and 1950s — does not celebrate, in the manner of the official Communist party press and foreign supporters, Cuba’s good performance in the HDI. Instead, it is trying to organize under extremely difficult conditions, on behalf of the political liberties necessary to defend the standard of living of the Cuban people and open up the possibility for a popular and democratically self-managed economy and polity.

Samuel Farber

Samuel Farber