RAFAEL ROJAS

BRIEFINGS ON CUBA, NOVEMBER 2020

CasaCuba, the Cuban Research Institute (CRI), and the Kimberly Green Latin American and Caribbean Center (LACC) at Florida International University (FIU),

Original and Complete Article: The New Cuban Executive Branch

YouTube Presentation: The New Cuban Executive Branch

Introduction:

For a year now, a new scheme of executive power organization has been in place in Cuba. The issue has gone unnoticed in the increasingly less articulated debate on the Cuban situation. After four decades of the concentration of power in the person of Fidel Castro, the new Cuban Constitution approved in February 2019 has shifted to a division of functions among the President of the Republic, the Prime Minister of government, and the highest authority in the Communist Party. The current leaders of these bodies, Miguel Díaz-Canel, Manuel Marrero, and Raúl Castro, rather than a deconcentration of power, have projected a differentiation of responsibilities that acquires meaning through the recipients of their decisions and messages.

Although the wording of the articles of the Constitution that define these functions is not without contradictions and lends itself to more than one misunderstanding, it is possible to notice the difference in roles. As “chief” and “representative” of the State (art. 128), the President makes decisions involving national citizenship and the international community. On the other hand, the Prime Minister, as “chief” and “representative” of the Government (art. 142), is defined as “responsible to the National Assembly of the People’s Power and to the President of the Republic,” for his own management and that of the Council of Ministers.

The highest ideological and political authority residing in the Communist Party determines the difference in roles in Cuban presidentialism. Because the president must also assume maximum responsibility within the Party—at the next eighth congress, to be held in April 2021, Raúl Castro will cede the position of First Secretary to Miguel Díaz-Canel—, the responsibilities of both holders are divided into the spaces of the National Assembly and the Communist Party. The verticality of a single, non-hegemonic political organization is preserved through a pyramidal logic that compensates for the distribution of functions at the apex.

In the pages that follow I propose an approximation to some aspects of the discussion about the new format of the organization of executive power in Cuba. The most apparent peculiarity of this restructuring of presidential power on the island is the strengthening of the Communist Party as a maximum instance of national leadership. The risks of overlapping or reproduction of functions between the president and the prime minister are controlled by a merger between the figures of the head of state and the supreme leader of the Communist Party. This risk control ensures the preservation of the political command unit amid the administrative distribution of power.

………………….

…………………

Conclusion:

I conclude by suggesting that the constitutional change that has taken place in Cuba gravitates towards a dispersion of the national executive power which, without some assimilation of parliamentary elements, the autonomization of civil society or, eventually, political pluralism, may be more conflicting than harmonious in a scenario, such as the one that will inevitably come, of a generational replacement of the country’s ruling class. Collegiate presidentialism such as that which aspires to be built in Cuba requires, for its own effectiveness, greater flexibility in the dimensions of political pluralism and electoral competence.

The move toward a presidential succession scheme, every two five-year periods, under a single Communist Party, as in China, seeks a permanent generational renewal in maximum leadership, which is secured with the sixty-year-old limit to be a presidential candidate in the first term. That would mean that in ten years most of the Cuban political class will be left out of the country’s top leadership. But as in China, generational renewal in executive power does not necessarily imply ideological and political easing or pluralization, given the immovable premises of the single Communist Party.

Given Cuba’s verticalist power structure, with a single Communist Party, which is supposed to be “the highest leading force of society,” and a vague distinction of roles between head of state (the President of the Republic) and head of government (the Prime Minister), a path to reform would be to truly strengthen the parliamentary elements of the system. In Article 128 the functions of the President are overreached, since he is given the power to “propose the election, appointment, suspension, revocation, or replacement” not only of the Prime Minister and the members of the Council of Ministers, but of the President of the People’s Supreme Court, the Prosecutor of the Republic, the Comptroller-General, and the authority of the Electoral Council.

Despite the sharing of executive functions, which would foster a collegial sense in presidential authority, the current constitutional regime engages in hyper-presidentialism, which subordinates legislative, judicial, and electoral powers to the head of state. An extension of the legislative powers of the National Assembly, in the process of division of powers, could help to better balance the Cuban political system. The increase in powers of the National Assembly would provide content for the representative government and the electoral process and would make it possible to compensate, at least in part, for the one-party system that limits political plurality on the island.

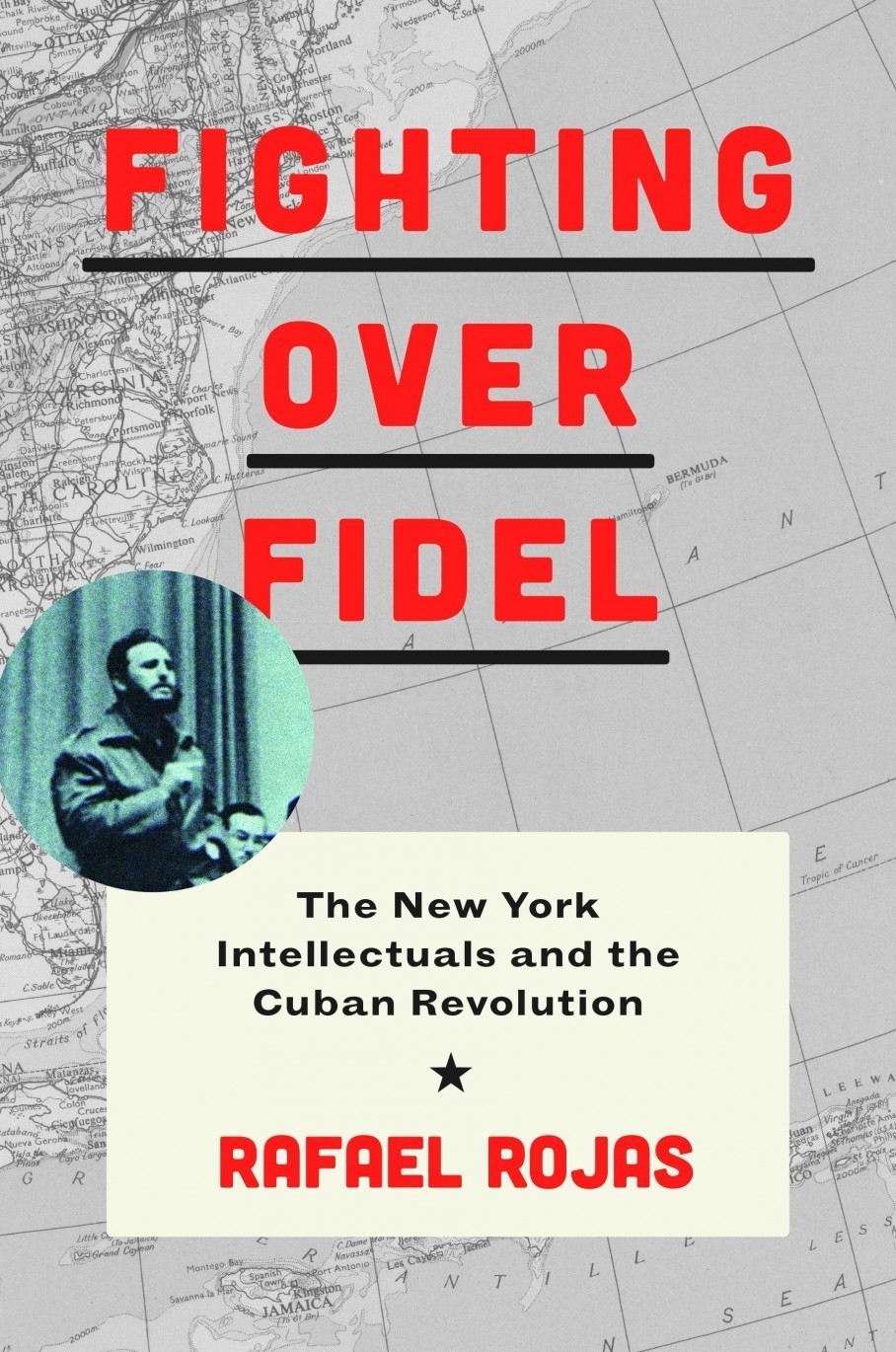

Rafael Rojas

Dr. Rafael Rojas is Professor of History at the Center for Historical Studies of the College of Mexico, where he also directs the journal Historia Mexicana. He is the author or editor of thirty books on the intellectual and political history of Cuba and Latin America, including Fighting over Fidel: The New York Intellectuals and the Cuban Revolution (2016) and Historia mínima de la Revolución Cubana (Minimal History of the Cuban Revolution, 2015). He is a member of the Mexican Academy of History since 2019 and was selected as one of the 100 most influential intellectuals in Ibero-America in 2014. He has been a visiting professor and scholar at Princeton, Yale, Columbia, and Texas-Austin. He is a frequent collaborator of the journal Letras Libres (Mexico) and the newspaper El País (Spain). He earned his B.A. in Philosophy at the University of Havana and his Ph.D. in History from the College of Mexico.