Original Document: HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH, 2022 REPORT, Cuban Country Chapter

https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2022

January 14, 2022

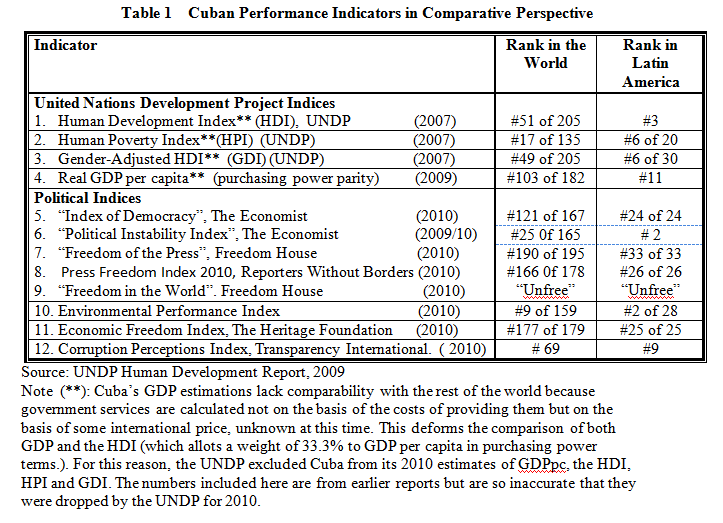

The Cuban government continues to repress and punish virtually all forms of dissent and public criticism. At the same time, Cubans continue to endure a dire economic crisis, which impacts their social and economic rights.

In July, thousands of Cubans took to the streets in landmark demonstrations protesting long-standing restrictions on rights, scarcity of food and medicines, and the government’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic. The government responded with brutal repression.

Arbitrary Detention and Short-Term Imprisonment

The government employs arbitrary detention to harass and intimidate critics, independent activists, political opponents, and others.

Security officers rarely present arrest warrants to justify detaining critics. In some cases, detainees are released after receiving official warnings, which prosecutors may use in subsequent criminal trials to show a pattern of what they call “delinquent” behavior.

Over 1,000 people, mostly peaceful demonstrators or bystanders, were detained during the July protests, Cuban rights groups reported. Officers prevented people from protesting or reporting on the protests, arresting critics and journalists as they headed to demonstrations or limiting their ability to leave their homes. Many were held incommunicado for days or weeks, violently arrested or beaten, and subjected to ill-treatment during detention.

Gabriela Zequeira Hernández, a 17-year-old student, was arrested in San Miguel de Padrón, Havana province, as she was walking past a demonstration on July 11. During detention, two female officers made her strip and squat naked five times. One of them told her to inspect her own vagina with her finger. Days later, a male officer threatened to take her and two men to the area known as the “pavilion,” where detainees have conjugal visits. Officers repeatedly woke her up at night for interrogations, asking why she had protested and who was “financing” her. Days later, she was convicted and sentenced to eight months in prison for “public disorder,” though she was allowed to serve her sentence in house arrest. She was only permitted to see her private lawyer a few minutes before the hearing.

In October 2021, Cuban authorities said that a demonstration being organized by a group of artists and dissidents for November 15 was “unlawful.” Later that month, the Attorney General’s Office released a statement “warning” people that they would face criminal prosecution if they “insisted” on carrying out a demonstration on November 15.

Cuban officers have also systematically detained independent journalists and artists. Victims include members of the coalitions of artists known as the “San Isidro,” “27N,” and “Archipelago” movements, as well as those involved in “Motherland and Life” — a viral song that repurposes the Cuban government’s old slogan, “Motherland or Death” (Patria o Muerte) and criticizes repression in the country. In many cases, police and intelligence officers appeared at critics’ homes, ordering them to stay there, often for days or weeks, in what amounted to arbitrary deprivations of liberty.

Officers have repeatedly used regulations designed to prevent the spread of Covid-19 to harass and imprison government critics.

Freedom of Expression

The government controls virtually all media in Cuba and restricts access to outside information. In February and August 2021, the Cuban government expanded the number of permitted private economic activities, yet independent journalism remained forbidden.

Journalists, bloggers, social media influencers, artists, and academics who publish information considered critical of the government are routinely subject to harassment, violence, smear campaigns, travel restrictions, internet cuts, online harassment, raids on homes and offices, confiscation of working materials, and arbitrary arrests. They are regularly held incommunicado.

In 2017, Cuba announced it would gradually expand home internet services. In 2019, new regulations allowed importation of routers and other equipment, and creation of private wired and Wi-Fi internet networks in homes and businesses.

Increased access to the internet has enabled many to communicate, report on abuses, and organize protests in ways virtually impossible a few years ago. Some journalists and bloggers manage to publish articles, videos, and news on websites and social media, such as Twitter and Facebook. Yet the high cost of—and limited access to—the internet prevents all but a small fraction of Cubans from reading independent news websites and blogs.

The government routinely blocks access to many news websites and blogs within Cuba and has repeatedly imposed targeted restrictions on critics’ access to cellphone data. On July 11, 2021, when the protests began, several organizations reported countrywide internet outages, followed by erratic connectivity, including restrictions on social media and messaging platforms.

On August 17, the government published Decree-Law 35/2021 regulating the use of telecommunications. The decree, which states its purpose is to “defend” the Cuban revolution, requires providers to interrupt, suspend, or terminate services when a user publishes information that is “fake” or affects “public morality” and “respect for public order.”

A “cybersecurity” resolution accompanying Decree-Law 35 contains sweeping provisions labeling protected speech—including publications that “incite protests,” “promote social indiscipline,” and “slander that impacts the prestige of the country”—as “incidents of cybersecurity” that authorities are required to “prevent” and “eradicate.”

Pre-existing Decree-Law 370/2018 still prohibits dissemination of information “contrary to the social interest, morals, good manners and integrity of people.” Authorities have used it to interrogate and fine journalists and critics and confiscate their working materials.

Political Prisoners

Prisoners Defenders, a Madrid-based rights group, reported that, as of September, Cuba was holding 251 people who met the definition of political prisoners, as well as 38 others for their political beliefs; another 92 who had been convicted for political beliefs were under house arrest or on conditional release.

Cubans who criticize the government risk criminal prosecution. They do not benefit from due process guarantees, such as the right to fair and public hearings by a competent, independent and impartial tribunal. In practice, courts are subordinate to the executive branch.

Many people who protested peacefully in July were sentenced through “summary” criminal trials that lacked basic due process guarantees, including the right to legal representation. Protesters were often tried for vaguely defined crimes, such as “public disorder” and “contempt.” In August, authorities said 66 people had been convicted in connection with protests; most did not have a lawyer. Some were acquitted on appeal.

In some cases, authorities sought or imposed disproportionate prison sentences against protesters whom they accused of engaging in violence, often by throwing rocks during protests.

On July 11, officers arrested José Daniel Ferrer, leader of the Cuban Patriotic Union, the main opposition party, as he was heading to a demonstration. On July 17, a prosecutor sent him to pre-trial detention, charged with “public disorder” for “deciding to join” the demonstrations. In April 2020, Ferrer had been arbitrarily sentenced to four-and-a-half years of “restrictions on freedom,” for alleged “assault.” On August 14, 2021, a Santiago de Cuba court required him to serve 4 years and 14 days in prison, ruling he had failed to “strictly respect the laws” and “have an honest attitude toward work,” legal conditions for people sentenced to “restrictions on freedom.”

Several artists, including Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara and Maykel Castillo, both of whom performed in the music video for “Motherland and Life,” remained in pretrial detention, facing arbitrary prosecution, at time of writing.

Travel Restrictions

Since reforms in 2013, many people who had previously been denied permission to travel to and from Cuba have been able to do so, including human rights defenders and bloggers. The reforms, however, gave the government broad discretionary power to restrict travel on grounds of “defense and national security” or “other reasons of public interest.” Authorities continue to selectively deny exit to dissenters.

In March 2021, Cuban authorities denied Karla Pérez, a Cuban journalist studying in Costa Rica, the possibility of returning home. An airline employee informed her during a stopover in Panama City that the Cuban government was refusing her admission. Pérez returned to Costa Rica, where she was granted refugee status.

Prison Conditions

Prisons are often overcrowded. Detainees have no effective complaint mechanism to seek redress for abuses. Those who criticize the government or engage in hunger strikes or other forms of protest often endure extended solitary confinement, beatings, restriction of family visits, and denial of medical care. The government continues to deny international human rights groups and independent Cuban organizations access to its prisons. In April 2020, to reduce the risk of the Covid-19 virus spreading in prisons, the government suspended family visits. This, coupled with authorities’ refusal to allow detainees to call their families, left many arrested during demonstrations incommunicado for days and, in some cases, weeks.

Labor Rights

Despite updating its Labor Code in 2014, Cuba violates International Labour Organization standards it has ratified on freedom of association and collective bargaining. While Cuban law allows the formation of independent unions, in practice the government only permits the operation of one confederation of state-controlled unions, the Workers’ Central Union of Cuba.

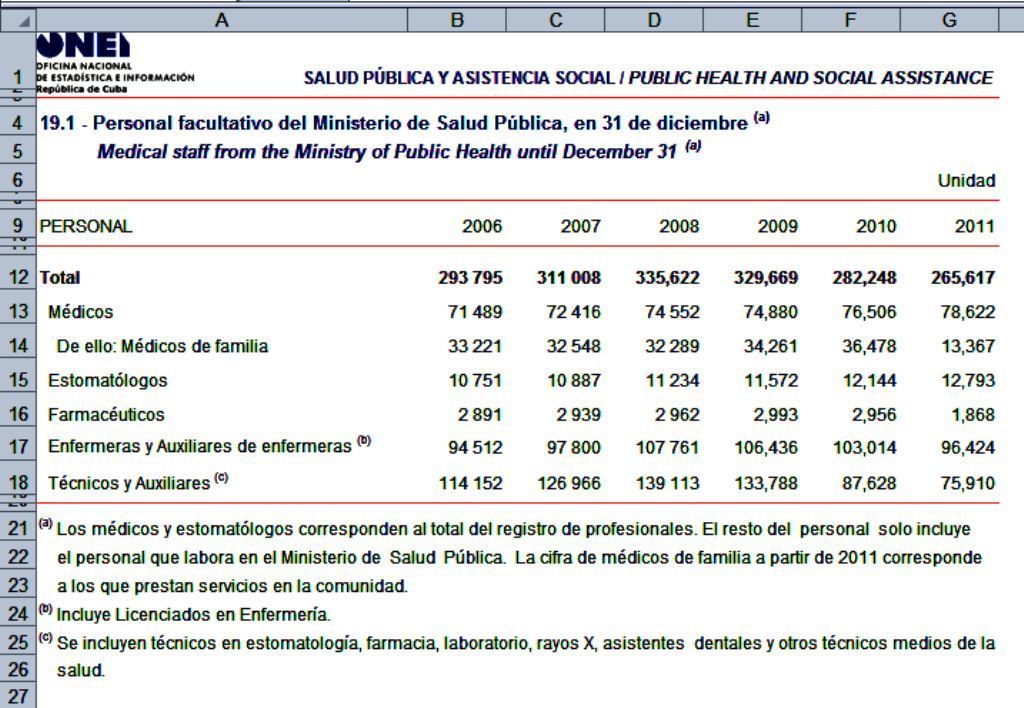

Cuba deploys tens of thousands of health workers abroad every year to help tackle short-term crises and natural disasters. They provide valuable services to many communities but under Cuban rules that violate their rights, including to privacy, liberty, movement, and freedom of expression and association. In 2020, Cuba sent some 4,000 doctors to help nearly 40 countries respond to the Covid-19 pandemic; they joined 28,000 health workers already deployed.

Human Rights Defenders

The government refuses to recognize human rights monitoring as a legitimate activity and denies legal status to local rights groups. Authorities have harassed, assaulted, and imprisoned human rights defenders attempting to document abuses.

In August, two officers appeared at the Havana home of the mother of Laritza Diversent, a human rights defender living in the United States, and threatened to prosecute Diversent and seek her extradition to Cuba. Diversent heads Cubalex, one of the main rights groups documenting abuses against people who demonstrated in July.

Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

The 2019 constitution explicitly prohibits discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity. However, many lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people suffer violence and discrimination, particularly in Cuba’s interior.

Early drafts of the constitution approved in February 2019 redefined marriage to include same-sex couples, but the government withdrew that proposal following public protests. The government said it would introduce a reform to the Family Code, which governs marriage, for legislative review and later carry on a referendum. In September 2021, the government made public a draft of the reform, which included a gender-neutral definition of marriage. It had not been approved at time of writing.

Sexual and Reproductive Rights

Cuba decriminalized abortion in 1965 and remains one of the few Latin American countries with such a policy. The procedure is available and free at public hospitals.

Key International Actors

The US embargo continues to provide the Cuban government with an excuse for problems, a pretext for abuses, and sympathy from governments that might otherwise more rigorously condemn repressive practices in the country.

In June 2021, the United Nations General Assembly voted overwhelmingly to condemn the embargo, for the 29th consecutive year; 184 countries supported the resolution, while the US and Israel opposed it, and Brazil, Colombia, and Ukraine abstained.

Under former President Donald Trump, the US government limited peoples’ ability to send remittances to Cuba from the US and imposed new restrictions on travelling to Cuba, banning cruise ship stops, educational trips, and most flights. In January 2021, the Trump administration designated Cuba as a State Sponsor of Terrorism, arguing that it had refused to extradite to Colombia members of the National Liberation Army (ELN) who had travelled to Havana to conduct peace talks with the Colombian government and stayed there.

In July 2021, the administration of US President Joe Biden condemned Cuban government abuses against protesters and imposed targeted sanctions on several officers credibly linked to repression against demonstrations. However, as of September, the US had not taken significant steps away from the broader policy of isolation that was entrenched during the Trump era and has failed to improve human rights conditions in Cuba.

In February, the European Union held a human rights dialogue with Cuba. EU High Representative Josep Borrell said in July that demonstrations in Cuba “reflect[ed] legitimate grievances.” He expressed concern about government repression and urged Cuba to release all arbitrarily detained protesters. The European Parliament adopted resolutions deploring Cuba’s human rights violations in June and September.

The Lithuanian legislature voted in July to oppose ratification of the EU’s Political Dialogue and Cooperation Agreement with Cuba, signed in 2016 but never ratified, because of Lithuania’s human rights concerns.

Since being elected to the UN Human Rights Council in 2020—its fifth term in the past 15 years—Cuba has opposed resolutions spotlighting human rights abuses in Eritrea, Ethiopia, Syria, and Nicaragua, among other countries.