By Yoani Sanchez, Huffington Post, 09/28/2012

Originals article here: Fidel’s “Revolutionary Collective Surveillancw

The stew was cooked on firewood collected by some neighbors, the flags hung in the middle of the block and the shouts of Viva! went on past midnight. A ritual repeated with more or less enthusiasm every September 27 throughout the Island. The eve of the 52nd anniversary of the founding of the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDR), the official media celebrate on its commemoration, a song intended to energize those who are a part of the organization with the most members in the entire country, and to dust off the old anecdotes of glory and power.

But beyond these formalities, which are repeated identically each year, we can perceive that the influence of the CDR in Cuban life is in a downward spiral. Gone are the days when we were all “CeDeRistas” and the acronym — with the figure of a man brandishing a machete — still shone brightly on the facades of some houses.

Amid the ongoing decline of its prominence, it’s worth asking if the committees have been a more of source of transmission of power to the citizenry, than a representation of us to the government. The facts leave little room for doubt. Since they were created in 1960, they have had an eminently ideological base, marked by informers. Fidel himself said it during the speech in which he announced their creation:

We are going to implement, against imperialist campaigns of aggression, a Revolutionary system of collective surveillance where everybody will know who lives on their block and what relations they have with the tyranny; and what they devote themselves to; who they meet with; what activities they are involved in.

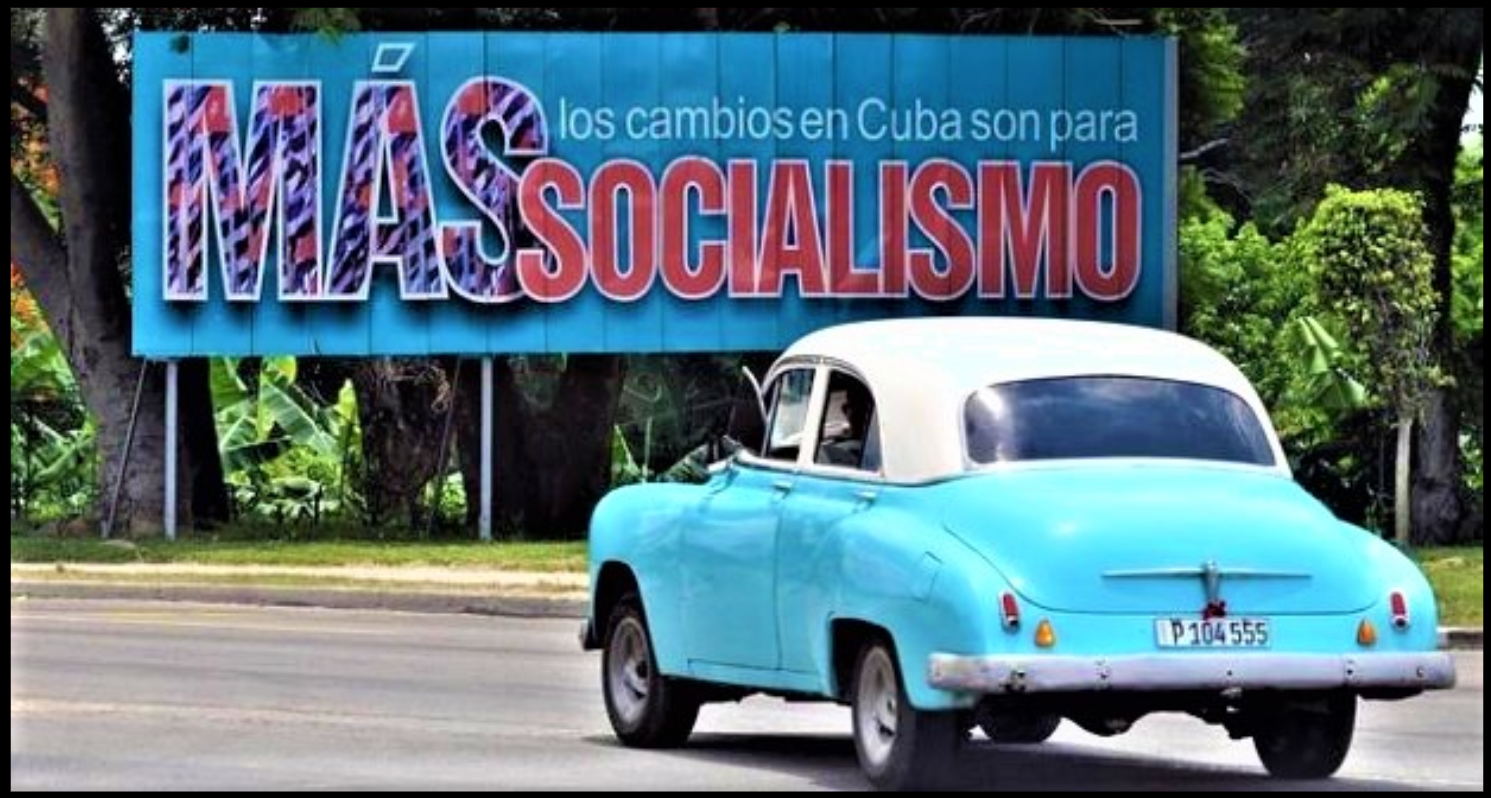

These words from the Maximum Leader are now difficult to find reproduced in full on national websites and newspapers. In part because, despite the unconditional support for the Commander in Chief, the current editors of these spaces know very well that such language is totally out of sync with the 21st century.

That is, what seemed like an exalted Revolutionary speech delivered from the balcony of the Presidential Palace, in the light of today has all the hallmarks of partisan despotism, of the grossest authoritarianism. Big Brother announcing his plan. If those words excited exaltation at the beginning of the sixties… they now provoke in many a mixture of terror, disgust and embarrassment for the man who spoke them.

The “sweeter” side of the CDR is the one that’s always related in official reports, talk about a popular force dedicated to collecting raw material, helping in the vaccination of infants, promoting blood donations, and guarding neighborhoods against crime. Put like that it appears to be an apolitical neighborhood group ready to solve community problems.

Believe me, behind this facade of representation and solidarity is hidden a mechanism of surveillance and control. And I’m not speaking from the distance of my armchair or from the lack of knowledge of a tourist who spends two weeks in Havana.

I was one of those millions of Cuban children who stockpiled empty jars or cartons, cut the grass and handed out anti-mosquito products in the CDRs all over the country. I was also vaccinated against polio and even tasted some plate of stew or other during the fiestas of this organization.

In short, I grew up as a child of the CDR, although when I reached adulthood I refused to become a militant among its ranks. I lived all this and I don’t regret it, because now I can conscientiously say from the inside that all those beautiful moments are dwarfed by the abuse, the injustices, the accusations and control that these so-called committees have visited on me and millions of other Cubans.

I speak of the many young people who were not able to attend university in the years of the greatest ideological extremism because of a bad reference from the president of their CDR. It was enough during a reference check from a school or workplace for some CDRista to say that an individual was “not sufficiently combative” for them to not be accepted for a better job or a university slot.

It was precisely these neighborhood organizations who most forcefully organized the repudiation rallies carried out in 1980 against those Cubans who decided to emigrate through the port of Mariel in what came to be known on the other shore as the Mariel Boatlift. And today they are also the principal cauldron of the repressive acts against the Ladies in White and other dissidents.

They have never worked as a unifying or conciliatory force in society, but rather as a fundamental ingredient in the exacerbation of ideological polarization, social violence, and the creation of hatred.

I remember a young man who lived in my neighborhood of Cayo Hueso, who had long hair and listened to rock music. The president of the CDR made his life so difficult, accused him of so many atrocities simply for the fact of wanting to appear as who he was, that he finally ended up in prison for “pre-criminal dangerousness.” Today this intransigent — this one-time “Frikie” from my block — lives with his daughter in Connecticut, after having his life and reputation dragged through the mud like so many others.

I also know of several big traders in the black market who assumed some post in the committees to use as a cover for their illegal activities. So many who took on the role of “head of surveillance” and were simultaneously the biggest resellers of tobacco, gas, and food in the whole area.

With few exceptions, I did not know ethically commendable people who led a CDR. Rather they attracted those with the lowest human passions: envy before those who prospered a little more; resentment of someone who managed to create a harmonious family; grudges against those who received remittances from family abroad; dislike for everyone who honestly spoke their minds.

This deceitfulness, this absence of values and this accumulation of grievances, have been been one of the fundamental causes for the CDRs’ fall into disgrace.

Because people are tired of hiding their bags so the informing neighbor can’t see it from their balcony. People are tired of the worn out sign in front of their house with the figure with the threatening machete. People are tired of paying a membership fee to an organization that when you need it takes the side of the boss, the State, the Party.

People are tired of 52 anniversaries, one after another, like a stale and nightmarish deja vu. People are tired. And the way to express this exhaustion is with the lowest attendance at CDR meetings, failing to go on night watch to “patrol” the blocks, even avoiding tasting the stew — ever more bland — on the night of September 27.

If doubts remain about why people get tired, we have the words of Fidel Castro himself on that day in 1960, when he revealed from the first moment the objective of his grim creature: “We are going to establish a system of collective surveillance. We are going to establish a system of Revolutionary collective surveillance!”