BOTH LATIN AMERICAN STATES REPRESS THEIR CITIZENS AND HAVE LITTLE REGARD FOR HUMAN RIGHTS, SO WHY HAVE THEY RECEIVED SUCH DIFFERENT TREATMENT FROM CANADA AND OTHERS?

BOTH LATIN AMERICAN STATES REPRESS THEIR CITIZENS AND HAVE LITTLE REGARD FOR HUMAN RIGHTS, SO WHY HAVE THEY RECEIVED SUCH DIFFERENT TREATMENT FROM CANADA AND OTHERS?

BY: YVON GRENIER, JUNE 21, 2018

Original Article: Cuba, Sí, Venezuela, No?

For years the Trudeau government has been exceptionally forceful in its condemnation of Nicolas Maduro’s budding dictatorship in Venezuela.

Canada imposed sanctions last September on key figures in the Maduro regime “to send a clear message that their anti-democratic behaviour has consequences.” In advance of April’s Summit of the Americas, Canada supported the announcement by host country Peru that Maduro would not be welcome to attend. In Foreign Affairs Minister Chrystia Freeland’s words: “Maduro’s participation at a hemispheric leaders’ summit would have been farcical.”

Freeland then characterized Maduro’s re-election on May 20 as “illegitimate and anti-democratic,” with Canada announcing further sanctions on key figures in the Maduro regime on May 30. The Organization of American States also passed a June 5 resolution that calls for an extraordinary assembly to vote on suspending Venezuela from the 34-member organization. Furthermore, Canada will not seek to replace its ambassador in Caracas, which amounts to suspending normal diplomatic relations. And most recently, in a speech at a Foreign Policy event June 13 in Washington, Freeland made a point of mentioning the country, saying that “some democracies have gone in the other direction and slipped into authoritarianism, notably and tragically Venezuela.”

The three main parties in Ottawa are strangely in lockstep to denounce the “erosion of democracy” in that once prosperous and democratic nation. But the Trudeau government is particularly combative. This is a strong contrast to our policy toward the only country in the region that is arguably a worse offender of democratic rights: Cuba. For if “Canada will not stand by silently as the Government of Venezuela robs its people of their fundamental democratic rights,” its policy toward Cuba has studiously been to stand by silently as the Castro brothers and now President Miguel Díaz-Canel robs the Cuban people of their fundamental democratic rights.

Comparing the state of democracy and human rights

The kind of elections held on May 20 in Venezuela, while clearly unfree and unfair, would represent a positive step toward pluralism in the one-party system of communist Cuba. For one, Maduro banned his main opponents from running, but he did allow two marginal opponents to campaign and compete for the presidency. Neither the Castro brothers nor Díaz-Canel ever had to run against anybody. For decades they were appointed unanimously by a rubber-stamp legislature completely controlled by the only party allowed in the country. Arbitrary detentions, total control of all branches of government by the executive, and violation of democratic rights are systematic and written into law on the island.

While Maduro is accused of violating the constitution of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, his Cubans counterparts do not need to disregard their 1976 constitution to trample democratic rights; its template is the USSR’s constitution of 1936 (imposed there under the leadership of Joseph Stalin). Cubans visiting Venezuela are pleasantly surprised at how relatively free the media and Internet access are compared to the reality at home. Monitoring organizations such as The Economist Intelligence Unit, Reporters without Borders and Freedom House rank Cuba lower than Venezuela in their indexes of democracy, press freedom, and civil and political rights.

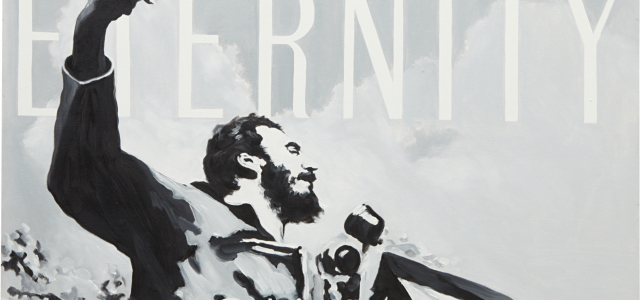

True, violent repression in Cuba is not as overt as it has been recently in the patria of Bolivar, where up to 160 civilians were killed by government forces during the massive street protests of last summer. Arguably, this is because Cuba is a more stable dictatorship, one that has already exported most of its opposition overseas. Short-term arbitrary arrests of human rights activists, independent journalists and dissonant artists appear sufficient to curb public criticism. Incidentally, the number of such arrests “have increased dramatically in recent years” according to Human Rights Watch. The dissident Cuban Commission for Human Rights and National Reconciliation reports 5,155 such detentions in 2017. As Venezuela becomes more totalitarian, and more of its aggrieved citizens rush to the exit, it will conceivably experience lower levels of violence and unrest. To recall: in the wake of the 1959 revolution, violent clashes with the “counter-revolutionary” opposition lingered on until mid-1965 in Cuba — Fidel Castro had become a master of counter-insurgency.

According to some observers, the humanitarian situation may be worse in Venezuela, primarily because of rapidly deteriorating access to food and medicine. But then again, it is hard to measure and compare. The Cuban government does not produce statistics on poverty on the island. We know most Cubans are very poor, especially if they don’t have access to remittances regularly sent by their family in exile, a source of income not (yet) available to most Venezuelans.

In other words, while the situation may be worse in some respects in Venezuela, the difference in criticism from outside those countries can be in no way because of Cuba’s superior “democratic behaviour.”

A Cuban fascination versus a newer crisis

And yet, under Trudeau, Canada’s relations with communist Cuba have returned to their former glory. Seasoned advocate of ever-closer Canada-Cuba relations, professor John Kirk, recently waxed eloquent at a conference in Barcelona about a newly found “warm embrace” between the two countries, with increased investments, cultural ties, and exchange of high-ranking government ministers in both directions. The Canadian government, according to its approach presented online, is about “unlocking opportunities” and trade, not about sanctions and denunciations of undemocratic practices.

Contrast Freeland’s comments on Maduro to Trudeau famously saying, in his statement on the death of Fidel, “on behalf of all Canadians,” that “Mr. Castro’s supporters and detractors recognized his tremendous dedication and love for the Cuban people.”

When CBC News senior parliamentary reporter Catherine Cullen asked Trudeau whether he believes Castro was a dictator, Trudeau tepidly replied: “Yes.” Yet he sends very mixed messages and seems to prefer overlooking the darker side of the Cuban regime.

One can think of several plausible explanations for this discrepancy, starting with the Trudeau family and its strange fascination with Fidel. Comparisons with US President Donald Trump’s man crush for Vladimir Putin come to mind. One cannot help but wonder if Freeland’s silence on Cuba (it would be a shoe-in addition to her Putin-Maduro axis of evil) is a concession made to the boss.

Other explanations, inter alia: Venezuela is (still) an OAS member, unlike Cuba, though if memory serves, Canada and other principled guardians of the OAS Democratic Charter are invariably sanguine about welcoming Cuba back to the hemispheric fold. Perhaps hostility toward communist Cuba is now perceived as an outmoded residue of the Cold War. Venezuela is a post-Cold War failing state, driven to the ground by a clumsy heir of Hugo Chávez, with no Bay of Pigs or even embargo (the US purchases most of Venezuela’s oil) as convenient excuses.

The most credible justification for such double standards is that Venezuela is in the midst of a crisis, with lots of moving parts, rather than being fully constituted (or ossified) like Cuba, where it is too late for pressures to work. The island fully “slipped into authoritarianism” — just as Freeland described Venezuela recently — in 1952 and then into totalitarianism in the 1960s. Former US President Barack Obama’s rationale for opening up to Cuba was ostensibly that the US tried to topple the regime for longer than he lived, and repeatedly failed. Venezuela is still in flux, increasingly isolated in the region and the world, and consequently, amenable to change under international pressure. Maybe.

Cuba’s impact on Venezuela

Be that as it may, Canada would be well advised to consider the responsibility of Cuban leaders in the current crisis in Venezuela. Cuban infiltration of Venezuelan state institutions is complete, as Cuban “advisers” can be found in virtually every single office, ministry or barrack of the Venezuelan state. Meanwhile, millions of Venezuelan oil dollars (even foreign oil bought by Venezuela and gifted to Cuba) flow into Cuba’s coffers. Venezuela had been an obsession of Fidel’s since the early 1960s and turning the country into a Cuban ally was his greatest foreign policy accomplishment. His smaller and poorer country astonishingly managed to infiltrate what is after all a larger and richer country. When Chávez declared in 2007 that Cuba and Venezuela were a “single nation” with a “one single government,” he was not kidding.

So, in other words, Canada is excoriating Venezuela for trying to emulate a country Canada is proud to have sunny relations with. To be provocative: would the Canadian government like Maduro more if he, like Cuban leaders, banned competitive elections altogether and closed the borders?

Leaving aside the complementary but separate discussion on what policy is best for Canada, one can at least say this: if Canada continues to pick its human rights policies à la carte, raging against violations in one country and glossing over possibly worse ones next door, the world may notice and take neither Canada’s principled position nor its not-so-principled position seriously. And if global consistency is too much to ask (after all, Canada seems to get along fine with China, Saudi Arabia, etc.), at least some regional evenness or just an explanation would be most welcome.