Archibald Ritter

February 1, 2016

Since 2010, Cuba has been implementing a redesigned institutional structure of its economy. At this time it is unclear what Cuba’s future mixed economy will look like. However, we can be sure that it will continue to evolve in the near, medium and longer term. A variety of institutional structures are possible in the future and there are a number of types of private sector that Cuba could adopt. Indeed it seems as though Cuba were moving towards a number of possibilities simultaneously.

The objective of this note is to examine a number of key institutional alternatives and weigh the relative advantages and disadvantages for each arrangement. All alternatives include some mixture of domestic or indigenous private enterprises, cooperative and “not-for-profit” activities. foreign enterprise on a joint venture or stand-alone basis, some state enterprises (in natural monopolies for example) and a public sector. However, the emphasis on each of these components will vary depending on the policy choices of future Cuban governments.

The possible institutional structures to be examined here include:

1. Institutional status-quo as of 2016;

2. A mixed economy with intensified “cooperativization”;

3. A mixed economy, with private foreign and domestic oligopolies replacing the state oligopolies;

4. A mixed economy with an emphasis on indigenous small and medium enterprise.

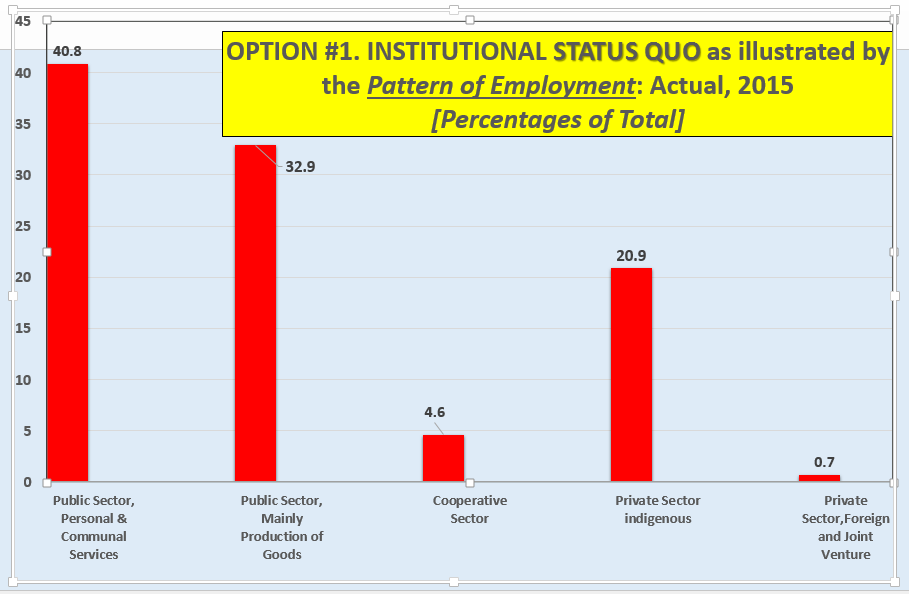

Option 1. Institutional Status-Quo as of 2016

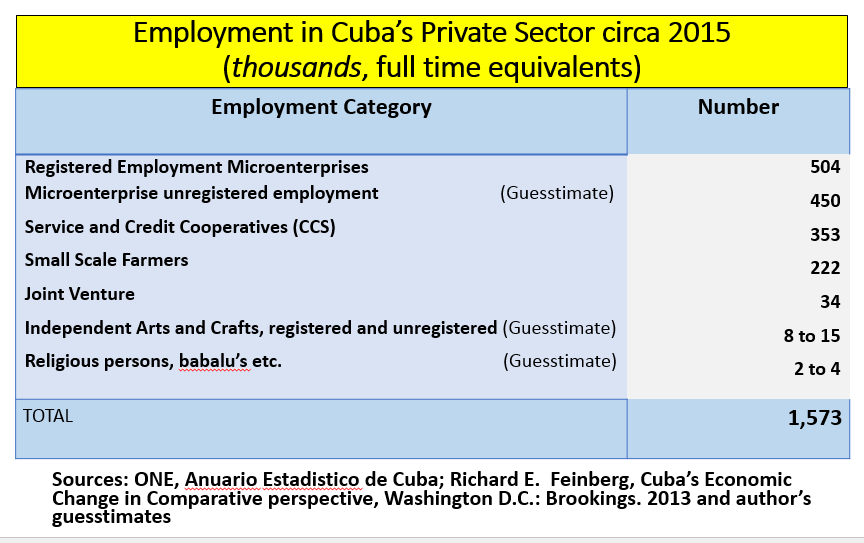

The institutional “status quo” is defined by the volumes of employment in the registered and unregistered segments of the small enterprise sector, the small farmer sector, the cooperative areas, the public sector, and the joint venture sector, plus independent arts and crafts and religious personnel. The employment numbers are mainly from the Anuario Estadístico de Cuba together with a number of guesstimates, some inspired by Richard Feinberg (2013). The guesstimate for unregistered employment in the small enterprise sector may seem exaggerated. However, a large proportion of the “cuentapropistas” utilize unregistered workers and a proportion of the underground economy does not seem to have surfaced into formally registered activities. These employment estimates by institutional area are presented in Table 1 and illustrated in Chart 1, which also serve as a “base case” for sketching the other institutional alternatives.

The current institutional status quo has a number of advantages but also some disadvantages. On the plus side, adhering to the status quo would avoid all the uncertainties and risks of a transition. It would maintain the possibility of “macro-flexibility,” that is the ability for the central government to reallocate resources by command in a rapid and large scale fashion. However, in view of the numerous “macro errors” made possible by a centralized command economy (the 10 million ton sugar harvest of 1970, the “New Man” endeavor, shutting down half the sugar mills), “macro-flexibility” may be a disadvantage. There are major advantages for the Communist Party in maintaining the institutional status quo in the economy, namely enabling political control of the citizenry (a disadvantage from other perspectives) and continuing state control over most of the distribution of income (also a disadvantage from other perspectives). The approach also helps foster good relations with North Korea (I am running out of advantages).

There are also major disadvantages. The centralized planned economy and public enterprise system generates continuing bureaucratization of production; continuing politicization of state-sector economic management and functioning; continuing lack of an effective price mechanism in the state sector and continuing perversity and dysfunctional of the incentive structure. The result of this is damage to efficiency, productivity and innovation.

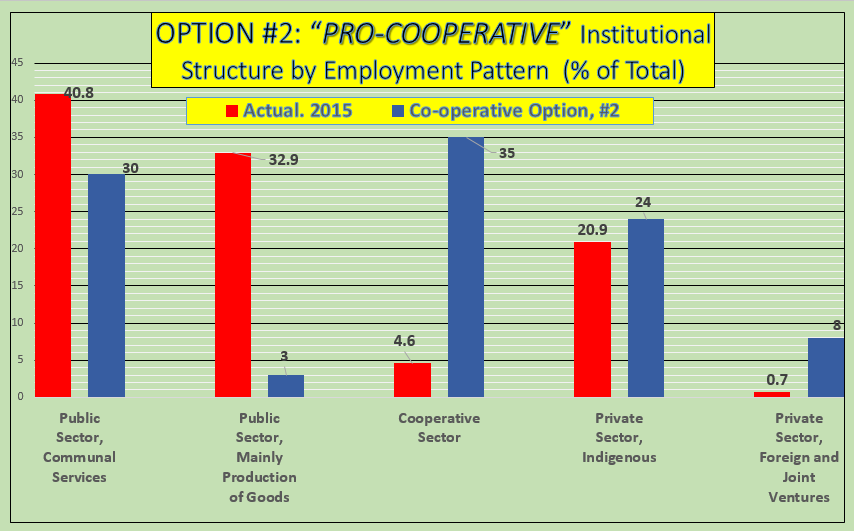

OPTION 2. Mixed Economy with Intensified “Cooperativization”

A second alternative might be to promote the authentic “cooperativization” of the economy in a major way. This would involve permitting cooperatives in all areas, including professional activities; opening up the current approval processes; encouraging grass-roots bottom-up ventures; providing import & export rights; and improving credit and wholesaling systems for coops.

A second alternative might be to promote the authentic “cooperativization” of the economy in a major way. This would involve permitting cooperatives in all areas, including professional activities; opening up the current approval processes; encouraging grass-roots bottom-up ventures; providing import & export rights; and improving credit and wholesaling systems for coops.

This approach has a number of advantages. First, it would strengthen the incentive structure and elicit serious work effort and creativity on the part of those in the coops. This is because worker ownership and management provides powerful motivation to work hard and profit-sharing ensures an alignment of worker and owner interests. This approach would generate a more egalitarian distribution of income than privately-owned enterprises. Cooperatives may possess a greater degree of flexibility than state and even private firms because their income and profits payments to members can reflect market conditions. Perhaps most important, democracy in the work-place through effective and genuine coops is valuable in itself and constitutes an advantage over both state- and privately-owned enterprise. [Workers’ ownership and control proposed in Cuba’s cooperative legislation is ironic and perhaps impossible since Cuba’s political system is characterized by a one-party monopoly. On the other hand it may help propel political democratization.]

The “second degree cooperatives” or “cooperative coalition of cooperatives” called for in the cooperative legislation is particularly interesting as it may permit reaping organizational economies of scale (a la Starbucks, McDonalds, etc. ) for small Cuban coops in these areas.

An emphasis on cooperatives would help to maintain ownership and diffused control and profit-sharing among local citizens, thereby promoting greater equity in income distribution.

But cooperatives also face difficulties and disadvantages. First, are they really more efficient than state and private enterprises? Generally speaking, cooperatives have passed the “survival test” but have not made huge inroads against private enterprise in other countries over the years. Perhaps this is because the “transactions costs” of participatory management may be significant. Personal animosities, ideological or political differences, participatory failures and/or managerial mistakes may occur. And for larger coops, complex governance structures may impair flexibility.

Second, Cuba’s actual complex co-op approval process is problematic and creates the possibility of political controls and biases. Certification of professional cooperatives is unclear. Also, the hiring of contractual workers is problematic

- The “Hire or Fire after 90 days” rule may curtail job creation;

- The 10% limit on contractual labor also may curtail job creation;

- Governance may be impaired if uncommitted workers have to join.

Finally, what will be the role of the Communist Party in the cooperatives? Will it keep out of cooperative management? Will Party control subvert workers’ democracy and deform incentives structures?

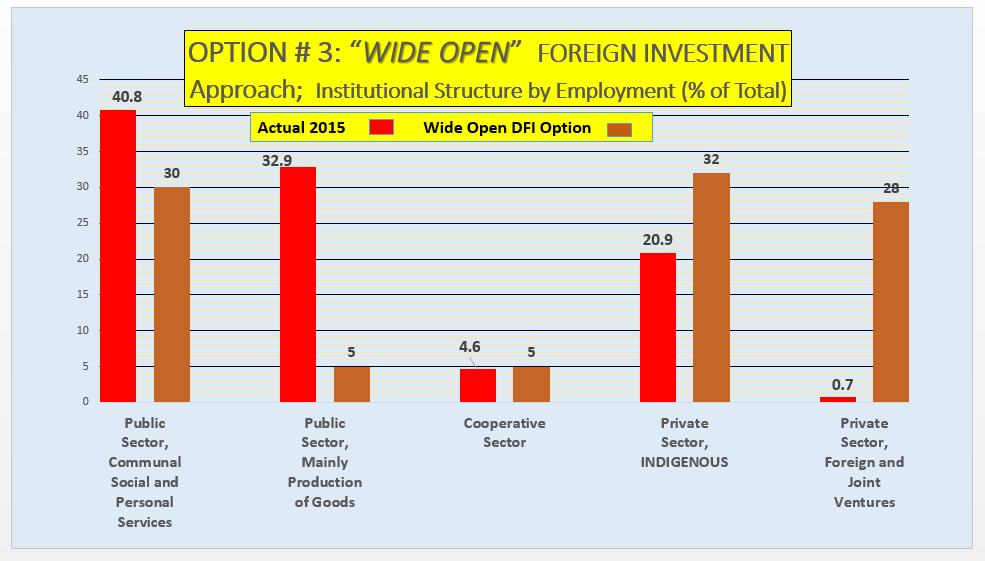

OPTION 3. Wide Open Foreign Investment Approach  A third possibility would be to open up completely to foreign investment. This would involve a rapid sell-off of state oligopolistic enterprises to deep-pocket foreign buyers such as China, the United States (in due course), Europe, Brazil, or elsewhere. The buyers might be the Walmart’s, Lowes, Subways, or Starbucks of this world, wanting to acquire major access to the Cuban market. This is a strong possibility if existing state oligopolies (e.g., CIMEX and Gaviota) were to be privatized in big chunks. The policy requirements for this approach to occur would be rapid privatization plus indiscriminate direct foreign investment and takeovers by large foreign firms.

A third possibility would be to open up completely to foreign investment. This would involve a rapid sell-off of state oligopolistic enterprises to deep-pocket foreign buyers such as China, the United States (in due course), Europe, Brazil, or elsewhere. The buyers might be the Walmart’s, Lowes, Subways, or Starbucks of this world, wanting to acquire major access to the Cuban market. This is a strong possibility if existing state oligopolies (e.g., CIMEX and Gaviota) were to be privatized in big chunks. The policy requirements for this approach to occur would be rapid privatization plus indiscriminate direct foreign investment and takeovers by large foreign firms.

This approach does have some advantages.

- It would generate large and immediate revenue receipts for the Cuban government;

- It would lead to large and rapid transfers into Cuba of financial resources; entrepreneurship and managerial talent; physical capital (machinery and equipment and structures); most modern technology embedded in machinery and equipment; and personnel where and when necessary;

- The results would be rapid productivity gains, higher-productivity work and rapid GDP gains.

However, there would also be disadvantages such as:

- Profits would flow out ad infinitum;

- Income concentration: profits to foreign owners (e.g. the Walton family of Arkansas who practically own Walmart) and profits to oligopolistic domestic owners;

- Oligopolistic economic structures would be damaging in the long run;

- There would be a strengthened probability of lucrative employment and ownership for the civilian and military “Nomenclatura”;

- Blockages or inhibitions to the development of Cuban entrepreneurship;

- “Walmartization” of Cuban culture; dilution of Cuban uniqueness;

- Further reduction of the potential for diversified manufacturing in Cuba (e.g. due to the Walmart/China mass-purchaser/mass-supplier symbiosis);

- Probably a blockage of export diversification.

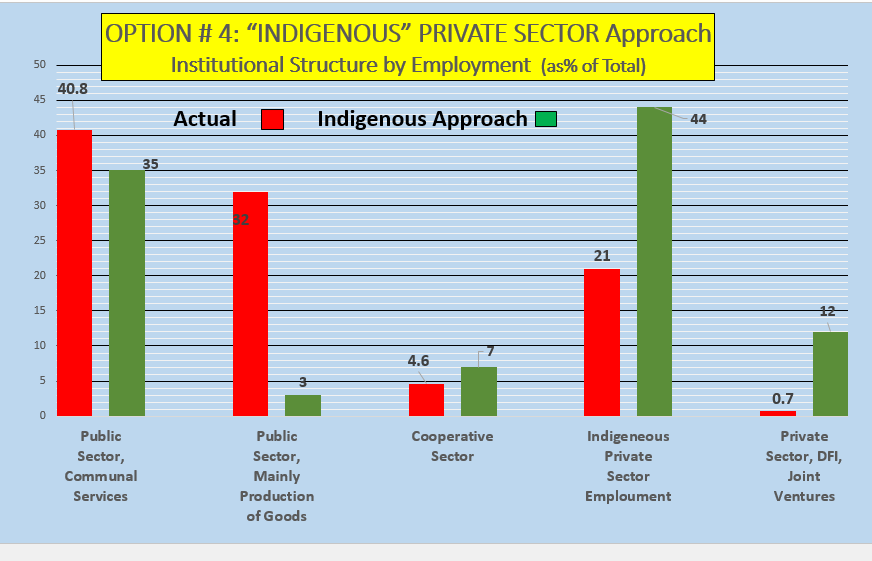

OPTION 4: Pro-Indigenous Private Sector in a Mixed Economy

A fourth possibility would be for Cuba to promote its own small-, medium- and larger enterprises in an open mixed economy. This would require

A fourth possibility would be for Cuba to promote its own small-, medium- and larger enterprises in an open mixed economy. This would require

- An “enabling environment” for micro, small and medium enterprise with a reasonable and fair tax regimen; an end to the discrimination against domestic Cuban enterprise (See Henken and Ritter, 2015, Chapter 7);

- The establishment of unified and realistic monetary and exchange rate systems;

- Property law and company law.

A liberalization of micro-, small and medium enterprise would also be necessary to release the creativity, energy and intelligence of Cuban citizens. This would involve open and automatic licensing for professional enterprises; an opening up for all areas for enterprise – not only the “201”; permission for firms to expand to 50 + employees in all areas; creation of wholesale markets for inputs; open access to foreign exchange and imported inputs; full legalization of “intermediaries” ; and permission for advertising.

This approach has some major advantages:

Oligopoly power would be more curtailed compared to Option 3;

- The economy would be more competitively structured with all the benefits this generates;

- It would encourage a further flourishing and evolution of Cuban entrepreneurship;

- It would permit the development of a diversified range of manufacturing and service activities and also a greater diversification of exports;

- It would provide a reduced role for the “Nomenclatura” of military and political personnel and their families that would otherwise gain from the rapid privatization of state enterprises;

- It would decentralize economic and thence political power and reduce the power for government to exert political influence through economic control;

- It would generate a more equitable distribution of income among Cuban citizens and among owners than Option 3;

- Profits would remain in Cuba;

- There would be a stronger maintenance of Cuban culture.

There would be some disadvantages with this approach.

- There would be no massive and immediate cash infusion to Government from asset sell-offs. Or is this an advantage? [more effective use of in-coming revenues]

- Perhaps there would be a slower macroeconomic recuperation;

- There would be slower inflows of technology, finance, managerial know-how – but more domestically controlled.

Conclusion

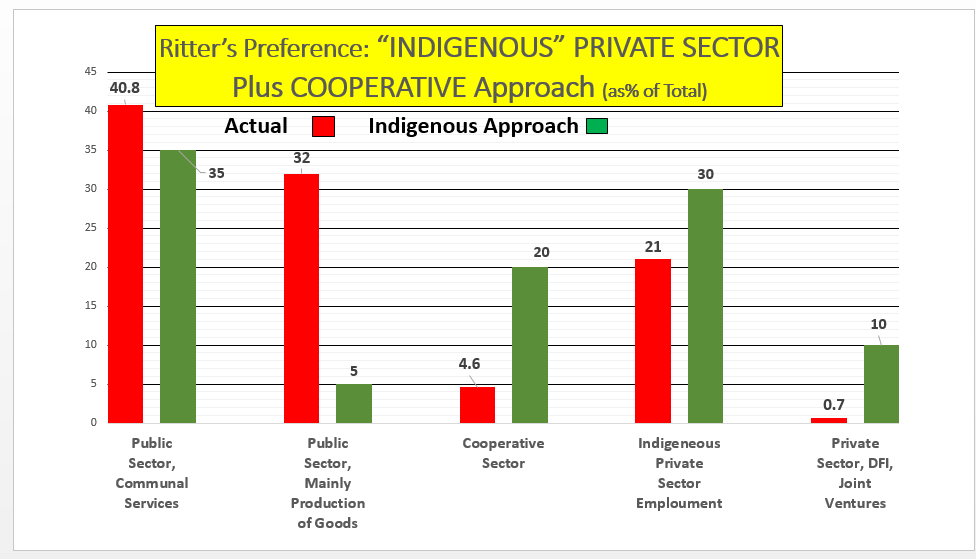

Most likely, Cuban policy-makers in the government of Raúl Castro, the government of his immediate successor, and future governments of a politically pluralistic character will design policies that ultimately will lead to some hybrid mixture of the above four possibilities. I of course will have little or no say in the process. However, my personal preference would be for an economy resembling the structure in the accompanying chart, with a large “indigenous” private sector, a significant cooperative sector, of course a large public sector for the provision of public goods, a small sector of government-owned enterprises, and a significant private foreign and joint venture sector.  So my bottom-line recommendations for current and future governments of Cuba would be:

So my bottom-line recommendations for current and future governments of Cuba would be:

- Utilize Cuba’s abundant resource — well-educated, innovative, strongly-motivated entrepreneurship — effectively, by further liberalizing the regulatory and fiscal regime for the indigenous micro-, small and medium enterprise sector, thereby also promoting Cuba’s indigenous economic culture;

- Use Cooperatives and “Coops of Coops” where possible;

- Avoid “Walmartization” & homogenization of Cuban economy and culture by utilizing an activist policy towards direct foreign investment.

Bibliography

Feinberg, Richard E., Cuba’s Economic Change in Comparative Perspective, Brookings Institution, 2013

Oficina Nacional de Estadísticas, Anuario Estadístico de Cuba, 2014

Ritter, Archibald and Ted Henken, Entrepreneurial Cuba, The Changing Policy landscape, Boulder Colorado: Lynn Rienner, 2015