Isbel Díaz Torres, HAVANA TIMES (Havana), June 21, 2013

Original Essay Here: Cuba: Wind Power vs. Oil

It would seem that local newspapers are intent on misinforming the public – both at home and abroad – about the Cuban government’s priorities with respect to the development of alternative energy sources.

A case in point was the news surrounding the recently-concluded congress of the World Wind Energy Association and the Renewable Energy Exhibition (WWEC 2013), held in Havana at the beginning of this month.

During a press conference, the director of Cuba’s Center for the Study of Renewable Energy Technologies (CETER), Conrado Moreno, declared that Cuba plans on developing the infrastructure needed to generate at least 10 percent of its electricity with renewable sources by the year 2030.

In this connection, the official lauded “the great strides in the development of wind power technologies” that Cuba has made in recent years, adding that the country has “a program the world can learn from.”

However, thanks to this impressive wind power “program”, whose installed capacity was less than 0.5 Megawatts (MW) in 2005, the country barely produced 12 MW of electricity in 2010.

That Cuba should present the congress with such an out-of-date figure (a figure which, in addition, is anything but impressive, representing a mere 0.08 % of the country’s entire energy output) should raise some eyebrows.

This figure may help explain why it will take thirteen years for the country to be able to generate 10 % of its energy with wind power and the other renewable sources of energy used on the island.

The fact of the matter is that Cuba currently has 9,343 wind turbines, 15 turbines and 4 wind farms in operation, for an installed capacity of 11.7 MW, a figure which places it beneath 68 other countries around the world.

As a way of comparison, in 2010 Nicaragua had a generating capacity of 40 MW (the equivalent of 5 % of the country’s total installed capacity), garnered from wind power technologies alone, while Cuba currently generates a mere 4 % of its electricity via renewable energy sources in general.

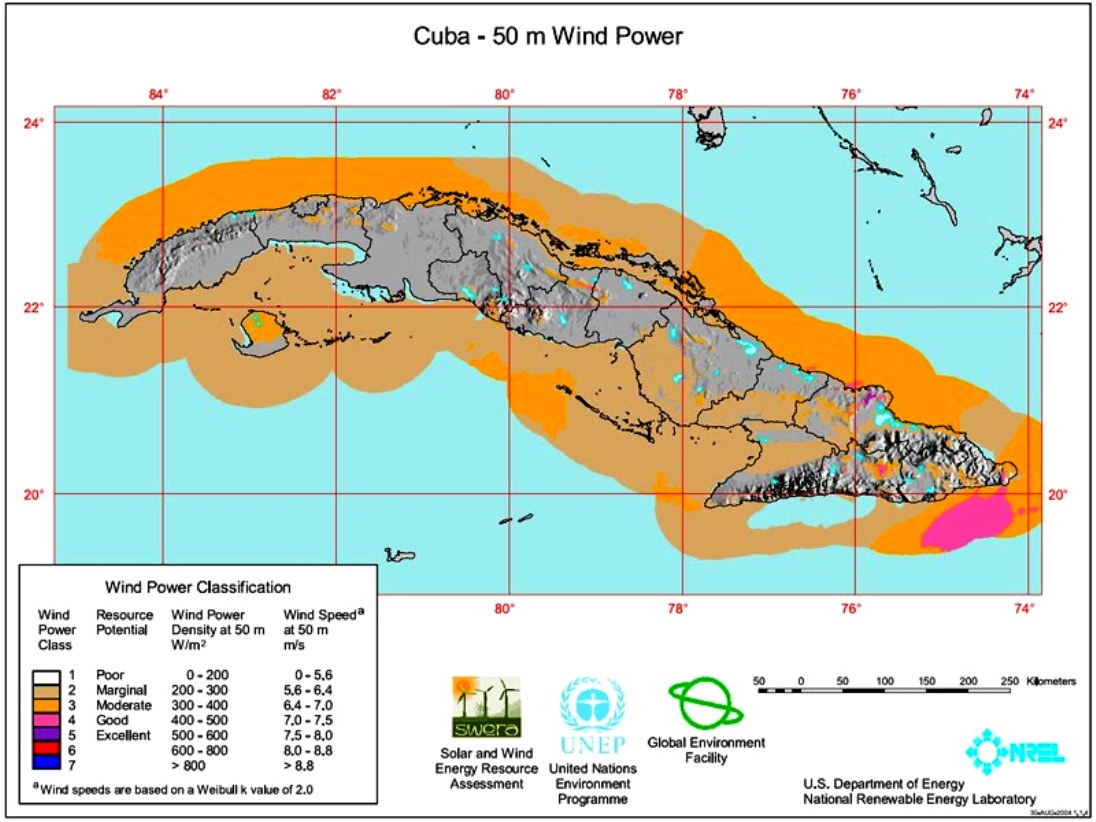

Local optimism, however, isn’t dampened by any of this, and experts continue to extol the virtues of Cuba’s largest wind farm (with a capacity of 51 MW), whose construction on the northern coast of the island’s eastern province of Las Tunas, a place of allegedly “ideal” wind conditions, is expected to be completed next year.

It is estimated that the wind farm could generate some 153 GW/h a year, allowing the country to cut down its fossil fuel consumption by some 40 thousand tons a year.

Not without a number of altercations at different levels, the Cuban government has managed to secure the environmental licenses required for the project from the pertinent agencies rather quickly, giving technicians a mere week to collect the required data.

Wind power is an abundant, renewable and clean energy resource which can aid in the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. Cubans, however, have never received any in-depth information regarding its benefits and limitations, nor have we ultimately been consulted in connection with its implementation.

Boasting of a relatively high Energy Return Rate* (18.1:1), wind power is cursed by one, significant limitation: its intermittence, that is, the fact that wind currents are not constant.

According to experts, wind currents on Cuba’s northern coastline are not uniform and are heavily influenced by local conditions, resulting from the interaction of trade and local winds and seasonal meteorological events.

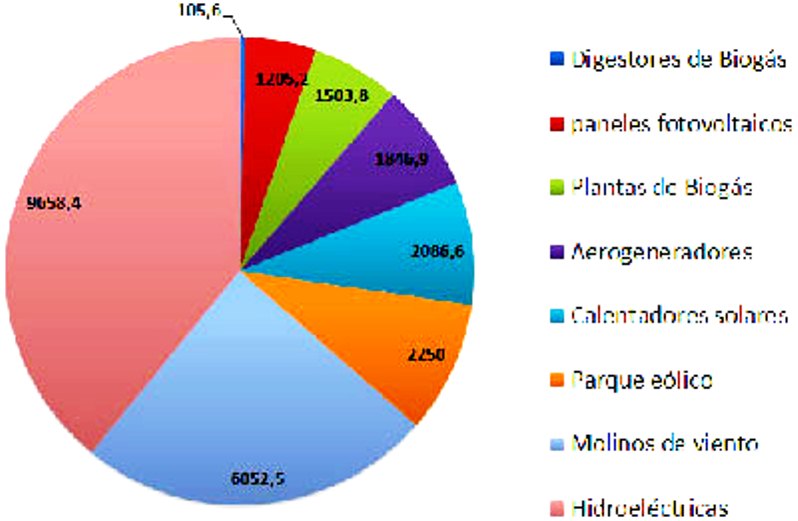

The contribution of biomass to Cuba’s energy production in the period 2000 to 2011. Figures in the equivalent of thousands of tons of oil.

Because of this, wind power can only ever supplement, never wholly replace, fossil fuel sources on the island, as the contribution of conventional energy sources is indispensible. In addition, as these conventional technologies operate in “backup mode” in this scheme, they consume a lot more fuel per KW produced every hour.

Fossil fuels are also consumed during the process of constructing the wind farm (during the mining of the materials, transportation and industrial processing) and all subsequent, indispensable maintenance operations.

Another inconvenient aspect of this technology is that winds must reach a certain, minimum velocity to be able to move the blades of the turbines. There is also a maximum wind velocity that, if exceeded, causes the entire network circuit to shut down.

In addition to the noise they produce and the disruption of the natural environment they represent, these wind farms reportedly affect the routes of migratory birds or the areas where these birds avail themselves of lateral winds, and the creation of access roads – and regular human presence, in general – damages local fauna.

The limitations of this technology, and the impact it has on the environment, ought not make us reject wind farms outright, but should, rather, make us re-think the way in which we have been implementing the technology and how congruous it is with the country’s global development strategy, as well as prompt us to demand accurate information in this regard.

Cuba has been working in the renewable energy field for decades without any type of legal regulations and without incurring any legal action from anyone. Recently, the director of CETER claimed that “a team of experts is working to implement it [the legal regulations] in a manner that suits Cuba’s economic development model.”

One of the more disquieting aspects of the wind power issue is how the Cuban media portray its state of development on the island, selling an image of a sustainable and ecological program, when, in fact, the country is heading down the more profitable road, caring little about its environmental impact.

Some statements we find in the press include: “In recent years, Cuba has made great progress in the development of wind power technologies.” / “Cuba has developed a wind power infrastructure (…) which only highly developed countries can boast of.” / “Cuba’s renewable energy program includes photovoltaic energy sources, which have experienced considerable development since the 1990s.” / “The ‘solarization’ of Cuba’s energy generating system.” / “The generation of electricity with renewable sources of energy will grow by 949 MW.”

As these grandiloquent reports on “green” energy sources are published, oil prospecting projects across Cuba’s platform continue in almost utter silence. This means that the government continues to invest heavily in this polluting energy source.

Cuban oil experts and government officials had anticipated that the country would be producing 90 % of its electricity with domestic oil reserves by 2010, but were unable to achieve this.

According to recent declarations made by Jorge Piñon, Associate Director of the Latin American and Caribbean Energy Program, Cuba could be producing as many as 250 thousand barrels of crude a day within five to seven years.

Enthusiastic Cuban government experts estimate that the Gulf of Mexico platform could contain as many as 20 billion barrels of oil. The U.S. Geological Service estimate is considerably more modest, calculating reserve volumes there at 5 billion oil barrels.

To date, results have not been exactly promising. The “Scarabeo 9” platform had to pull out of the so-called Exclusive Economic Zone last year, following three unsuccessful attempts to find oil in the area.

To top things off, a few weeks ago, the Russian oil company Zarubezhneft decided to push back prospecting efforts to 2014, reporting “complications of a geological nature.”

These fiascos do little to burst the oil bubble of the Cuban government, which continues to spend millions in prospecting infrastructure.

Following the intensive modernization of the country’s thermoelectric plants ten years ago, Cuba is now working to expand its refinery in Cienfuegos, construct an oil duct connecting Cienfuegos and Matanzas, build a storage facility that can house 600 thousand oil barrels in Matanzas and complete the vast commercial port in Mariel (a billion dollar investment), and in many other related projects.

In the meantime, Venezuela continues to ship an average of 100 thousand barrels of oil to the island every day, 30 thousand of which are financed by PetroCaribe, as per a 25-year agreement with an interest rate of only 1 % signed with the island.

What will Cuba do in 2030, then, when it has the infrastructure to generate 10 % of its electricity using renewable energy sources? Will it have found the oil it seeks by then? Will it abandon the idea of using this oil for energy production? Will it sell it to the United States?

According to the most recent report issued by the National Intelligence Council, the CIA bureau responsible for analyzing and anticipating geopolitical and economic developments around the world, by 2030 the United States (the world’s largest importer of hydrocarbons today) will be entirely self-sufficient in terms of oil resources, and the world’s oil market could well collapse as a result of this.

We must acknowledge that hydrocarbons continue to be the world’s chief energy resource and that, like the rest of the world, Cuba does not have the infrastructure or programs needed to make the transition to a post-oil economy.

Many experts agree that the diversification and expansion of energy sources must become one of the pillars of Cuba’s future energy production scheme.

A broad range of alternative energy sources, from natural gas (the least polluting of all hydrocarbons) to renewable sources such as ethanol extracted from sugar cane, wind power, solar energy and bio-gas could be developed in Cuba.

That said, according to Cuba’s National Statistics Bureau, the amount of energy Cuba produced using renewable sources in 2011 was nearly 2 million tons less of oil equivalent than in 2001. This report reveals a marked decline in the use of these alternative energy sources in the course of the decade, a trend which coincides with the “oil enthusiasm” of recent years and the shutting down of numerous sugar refineries across the country.

The greatest drop was experienced in the use of biomass (chiefly sugar cane bagasse). Hydroelectric plants are the most widely used forms of primary energy production, while wind power generators occupy the fifth place among renewable energy technologies used on the island.

In recent years, experts in the field have voiced complaints that Cuba’s Electricity Law does not particularly encourage the use and commercial promotion of renewable energy sources.

The truth of the matter is that none of these sources of energy afford us one, magical solution to the problem of the energy deficit, and many of these technologies pose serious bioethical questions. If anything, they underscore the fact that the demands of contemporary society, engineered by global capitalism, are insatiable.

The policy of development at all costs, planned obsolescence, the alienation of individuals and collectives in productive processes, the outsourcing of production, the deification of consumption, policies which protect banks and international financial institutions, these and many other problems are at the root of the crisis faced by the energy sector and, I dare say, our civilization as a whole.

In the words of social anthropologist Emilio Santiago Muiño, “a sustainable system which is not grounded in marketing implies a profound change in lifestyle.”

Cuban economists and politicians do not appear to be equipped with the mentality needed to understand this. They are prey to the same ills mentioned above, and they are irresponsibly supported, in their policies, by a good part of Cuba’s scientific community, which does little to re-think the idea of “development” that prevails today.

At the recently-concluded world conference on wind power, Cuba sought to put together a business portfolio with a view to signing international agreements and broadening productive capacities in the sector.

This, which appears commendable, is congruous with the pragmatism of calculating analysts within and outside Cuba, who seek a painless reinsertion of the island’s economy in the international market.

*Energy Return Rate (ERR): Amount of primary energy that must be invested in order to produce energy with a given source.

Alternative energy source production in Cuba.