Geopolitical Intelligence Services AG, Politics.

February 3, 2022

The Cuban regime struggles to reconcile its ideological commitment with a populace that has few ties to the revolution. The likely consequence is enduring state repression.

In a nutshell

- Cubans are increasingly removed from the revolution

- Reforms are unlikely to come from anywhere but the military

- Increasing state repression is most likely

For over six decades Cubans have lived under two ideological stipulations: that they owe the revolution and its leaders total, undivided loyalty; and that they accept socialism, not capitalism, as the reigning economic system, now and forever. But today’s regime struggles to uphold these mandates. Though governed by a Leninist elite, only 15 percent of Cubans experienced the enthusiasm of the Revolution’s early days, times that are now a distant memory.

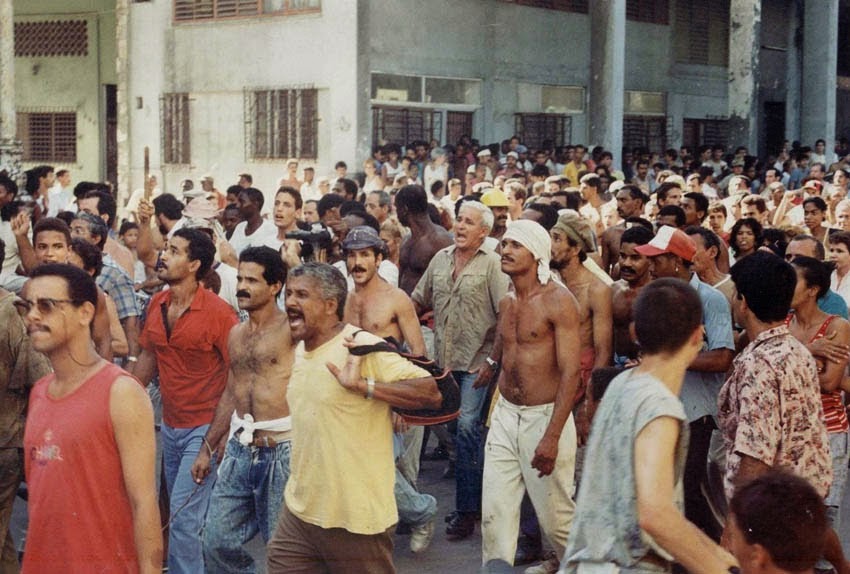

The erosion in the revolutionary spirit is evident in the estimated million and a half Cubans who have self-exiled, and the continued search for visas to the United States or Spain. Most fundamentally, it is clear in the repeated explosions of public protests, such as the “Maleconazo” protest of 1994, the November 2020 “sit down” of artists before the Ministry of Culture, and the recent, massive “Patria y Vida” demonstrations in several major cities. A social mobilization program for November 15 of this year was quashed by the repressive actions of military, police, and armed members of the Communist Party.

August 5, 1994 protests in Havana: the “Maleconazo “

And still further evidence of this erosion is found in the posture of the majority of intellectuals who reject Marxist economic organization and opt for opening the society to private enterprise and international trade.

Influential Cubans in the diaspora have been quick to identify the growing agitation for reform as an inevitable social movement. Arguably, among the earliest observers of this shift toward demands for greater freedom of economic activities is the dean of exiled economists, Carmelo Mesa-Lago, who sees the reform process as “unstoppable” and predicts that if the leadership tried to reverse it, “people will simply ignore them … [and] the possibility of revolt will increase.” In a similar tone, veteran researcher William LeoGrande predicts that “how Cuba’s institutions adapt to this new reality will be the principal determinant shaping the future of Cuban politics.”

How, then, to unravel in an intelligible way the probable future of this paradoxical socialist system? Three scenarios are suggested, each with the degree of probable occurrence indicated.

Resistance to reform

The most likely scenario is enduring and increasing state repression, as opportunistic economic reforms move along at a snail’s pace.

At no time will these reforms be allowed to threaten the existing political establishment. It took 10 years to implement the timid legalization of private occupations (cuentapropismo) of February 2021; and, even then, the most profitable occupations, such as doctors, lawyers and engineers were excluded.

The ability of the dictatorship to overcome challenges to the system has been amply demonstrated.

Despite this hesitancy, some experts maintain that there are at least five factors that make it impossible to retain repressive policies: the domestic economic crisis; the absence of any significant guarantees by a foreign geopolitical ally such as the Soviet Union or Venezuela; the loss of the monopoly over social media; what Fidel and Raul Castro repeatedly identified as the sclerotic self-preservation of the bureaucratic class; and, contextualizing all the above, the pressures exerted by two generations exhausted from decades of food shortages and a lack of liberties.

And yet, all of that said, the ability of the dictatorship to overcome innumerable challenges to the system has not only been amply demonstrated, but stiffens the spine of these heavily invested in its survival. Of course, it also motivates those determined to reform the system.

Diaspora investment

An outcome with a low probability over the short-to-medium term hinges on whether the U.S. Congress modifies or abolishes the Helms-Burton Act, which governs American relations with Cuba, and the Cuban government changing its prohibition of investments from the Cuban diaspora. Should these events take place (regardless of which comes first), there exists in the Cuban community abroad a real nostalgia for their erstwhile country and arguably more capital – through remittances and direct foreign investments – than could be available from U.S. foreign aid or international lending agencies.

Potential changes in the sugar sector are one prominent, potential outcome. The traditional Cuban saying, “sin azucar no hay pais” – without sugar, there is no country – describes one of the great ironies of the nation divided between island and diaspora.

The case of the Fanjul family is illustrative. With their sugar holdings expropriated by the Revolution, the Fanjuls invested what they managed to get out of Cuba in Florida sugar. By 2019, the Fanjul Corporation was worth $8 billion and produced 7 million tons of cane – six times what Cuba as a whole produced that year. The senior Fanjul, Alfonso (“Alfy”), traveled to Cuba in 2012 and 2013 and, “with tears in his eyes,” visited his family’s colonial-era home. He told the Washington Post that “under special circumstances” he would be willing to invest in Cuba: namely, Cuba would have to roll back many of its baked-in, anti-free trade and private property laws and take a more positive attitude toward the Cuban American community. Partly because of the opposition of powerful Cuban American politicians, chances of either happening in the near or medium term at the moment seem very slim.

Military-led reform

A scenario with very long odds but one that is not to be ignored would see the rise of a modernizing Cuban military.

The Cuban government is certainly conscious of the possibility. Most telling is their reaction to the recent seminar held at the University of St. Louis campus in Madrid where the role of the Cuban military was discussed. In a presentation to the conference, former Spanish President Felipe Gonzalez described the role of the Spanish armed forces in making possible the transition to democracy. Other cases discussed were those of Peru, Venezuela, and Turkey. Among the Cubans present were Yunior Garcia Aguilera, the main leader of the Archipelago Movement, and veteran oppositionist Manuel Cuesta Morua.

The former was later forcefully confined to his house before going into exile; the latter incarcerated. Meanwhile, in a subsequent Cuban television program, a “secret agent” called Leonardo revealed that he had been present at the conference, which he described as “a training seminar on how to subvert the Cuban military.”

Some 25 percent of the Central Committee of the CCP’s Political Bureau belong to the military. They are managing an estimated 75 percent of the economy. The military, with its 35,000 members – and not the 800,000 members of the Communist Party – is now the leadership institution in Cuba. (Bloomberg published a revealing report on General Luis Alberto Rodríguez, chairman of the largest business empire in Cuba, a conglomerate that comprises at least 57 companies owned by the military.)

Who is going to manage affairs if the command structures of the state are dismantled?

As is the case in all modernizing militaries, they manage their holdings under a rigid set of financial benchmarks – a decidedly capitalist administrative mode. This veritable military-economic oligarchy fits a category, the “modernizing oligarchy,” that is well known in the sociology of development as defined by Edward Shils: political systems controlled by bureaucratic and/or military officer cliques, in which democratic constitutions have been suspended and where the modernizing impulse takes the form of concern for efficiency and rationality.

“Modernizing oligarchies,” says Mr. Shils, “are usually strongly motivated toward economic development.” Samuel Huntington also notes that multiparty systems which promote freedom and social mobility lose the concentration of power necessary for undertaking reforms. “Since the prerequisite of reform is the consolidation of power, first attention is given to the creation of an efficient, loyal, rationalized, and centralized army: military power must be unified,” he writes.

Although a long shot, it cannot be disregarded that it might be the military that will set the developmental priorities and enforce them in the initial stages of the reforms most of Cuba seem to yearn for.

Scenarios

The task facing any prospective reformers is an enormous one, since all economic sectors were placed under state control in 1976. In addition, key preconditions for a modern capitalist economy – such as a proper legal system or tax code, and capital markets – do not exist. The punitive U.S. embargo does more than just cut them off from international lending agencies; it is one of the most all-around onerous embargoes ever imposed by the American government.

Given all this, who is going to manage affairs if the command structures of the state are dismantled? In particular, who is going to limit the grabbing of major parts of the privatized structures by criminal gangs – as occurred when the Soviet system was dismantled? Scholars such as the Canadian military historian Hal Klepak and the exiled Cuban sociologist Haroldo Dilla argue that only the military can pull this off. Interestingly, Messrs. Klepak’s and Dilla’s conclusions mirror those of two RAND scholars, who decades ago made a recommendation that flew in the face of the “gambler’s fallacy” that has governed Washington’s approach since the beginning of this conflict.

Policymakers, they argued, should be prepared to shift policy tracks or possibly recombine different elements from two or more options. One of the options recommended was to explore “informational exchanges and confidence-building measures” between the American and Cuban armed forces. Their reasoning is based on sound sociology: “Of all the state institutions, the military and security organs remain most critical to the present and future survival of the regime.” And, one might counterintuitively add, the only ones capable of reforming it.

The third scenario might indeed be a long shot, but the military is the only institution that, if the situation arises, has a chance to pull off reform of that calcified regime