Por Pável Vidal, economista cubano y profesor de la Universidad Javeriana en Cali, en Colombia

IPS Inter Press Service, 6 de enero de 2017

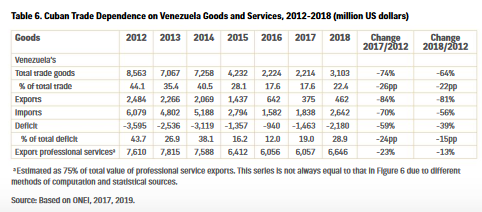

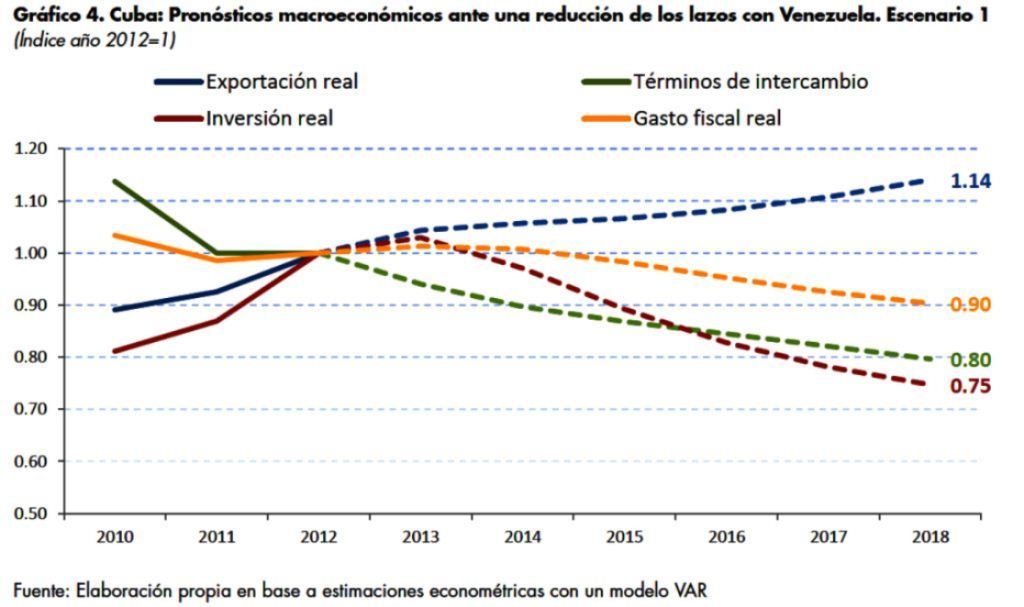

CALI, Colombia, 30 dic 2016 (IPS) – Los datos macroeconómicos de cierre del año proporcionados por el gobierno cubano confirman las proyecciones de que Cuba entraría en una recesión como resultado del shock venezolano.

La producción de bienes y servicios en 2016 cayó 0,9 por ciento. Esta es la primera recesión económica desde el año 1993, en que el producto interno bruto (PIB) se hundió 15 por ciento tras la desaparición de la Unión Soviética.

Desde finales de 2014, tras la dramática caída del precio del petróleo y la consecuente crisis de la economía venezolana, la recesión cubana era altamente probable, si además sumamos una respuesta de la política económica cubana insuficiente ante la magnitud del shock que se avecinaba.

Las relaciones con Venezuela están formadas bajo acuerdos muy singulares entre ambos gobiernos, con precios y facilidades financieras que se alejan de las prácticas más habituales en el comercio internacional.

Por tanto, no se trata simplemente de buscar nuevos mercados para el comercio que ya no se puede realizar con Venezuela, sino que hay que hacerlo de una manera diferente e impulsando nuevos sectores económicos, dado que parece bastante improbable alguien más reciba los médicos cubanos y nos venda petróleo bajo las mismas condiciones.

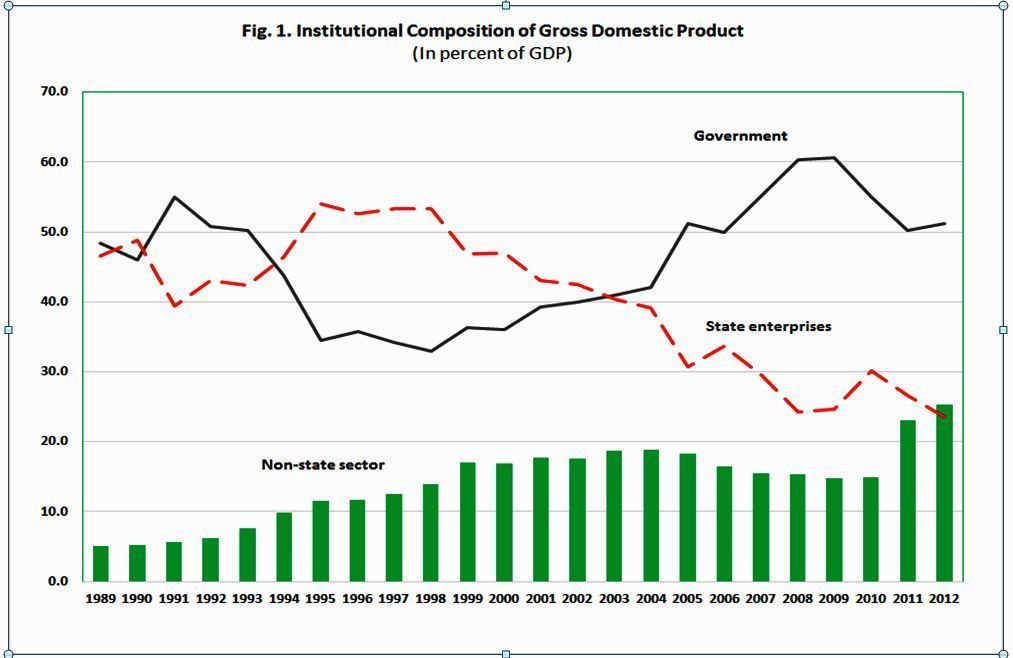

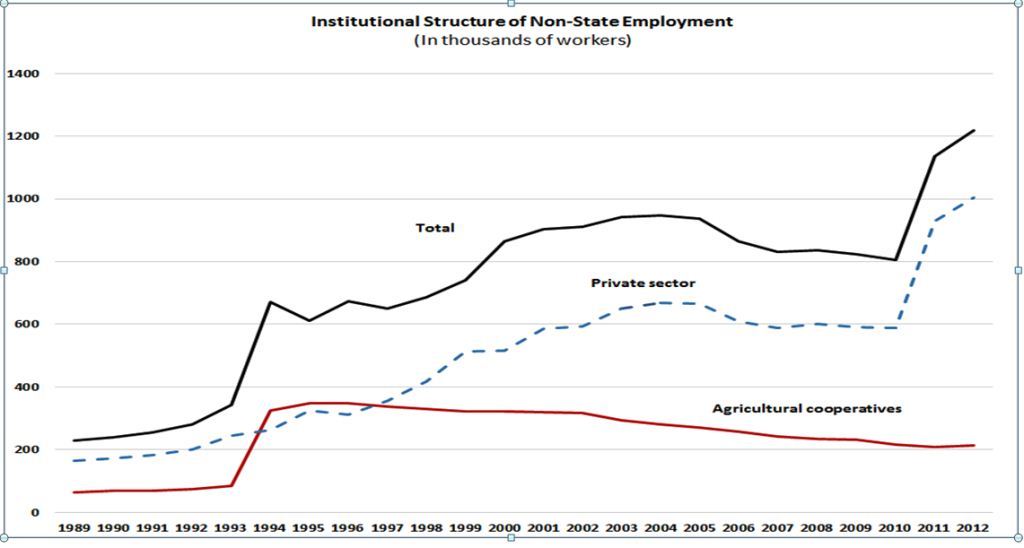

Por eso era tan importante comenzar cuanto antes la diversificación de las relaciones internacionales y la liberalización de las capacidades internas en búsqueda de un incremento de la productividad y mayor eficiencia en la producción nacional. La atracción a gran escala de inversión extranjera, la devaluación de la tasa de cambio oficial y la convergencia monetaria, una reforma más profunda de la empresa estatal y la ampliación de los espacios al sector privado y las cooperativas, eran algunos de los pasos que parecían factibles y coherentes con las reformas ya iniciadas.

¿Por qué no se dieron algunos o todos estos pasos? Pueden esgrimirse múltiples explicaciones.

Porque no hay claridad o convencimiento de hacia dónde dirigir el modelo económico cubano. Porque las fuerzas de resistencia a los cambios han ganado por ahora la partida. Porque las necesidades de tantos cambios sobrepasan la capacidad institucional y técnica para administrarlos todos al mismo tiempo. Porque el embargo estadounidense sigue impidiendo la llegada de inversionistas extranjeros institucionales. Porque de verdad se cree que una reforma muy lenta y haciendo experimentos es la única vía efectiva. Y seguramente se podrían añadir algunas otras explicaciones.

Por la razón que sea, el resultado final es que las reformas han perdido velocidad en vez de apresurarse, y transcurridos 10 años, no hay resultados muy alentadores cuando se examina la productividad, el salario medio o un sector específico como la agricultura.

Los anuncios de nuevas transformaciones son cada vez más dilatados. Cuba parece vivir en una dimensión del tiempo diferente, es como si un año de Cuba equivale a un mes en el resto del planeta.

Sin embargo, el espacio en el que opera la economía no está aislado, compite con otros destinos para los capitales internacionales, se rezaga tecnológicamente, pierde peso relativo en la región, y sufre los ciclos de los mercados internacionales y las crisis de sus principales aliados económicos.

Las perspectivas para 2017 y el rol de los bonos públicos

Para el año 2017 el gobierno planifica una mejoría en la situación de la economía, algo que es contrario a las proyecciones que habíamos efectuados. El gobierno planifica un aumento de dos por ciento del PIB.

Este aumento del PIB para 2017 está sustentado en dos factores esenciales. Uno, la esperanza que mejore la situación de la economía venezolana tras los últimos aumentos del precio del barril de petróleo; y dos, el gobierno cubano pone en práctica una política fiscal expansiva anticíclica.

En su discurso en la Asamblea Nacional el 27 de diciembre, el ministro de Economía y Planificación, Ricardo Cabrisas, plantea que: “Las proyecciones de los portadores energéticos para el venidero año permiten respaldar niveles similares a los del 2016…”

Muy probablemente esta perspectiva tiene como punto de partida el incremento que ha presentado el precio del barril de petróleo durante los últimos tres trimestres y algunas proyecciones internacionales que lo sitúan en mayores niveles para el año 2017, lo cual favorece el desempeño de la economía venezolana y abre la posibilidad de que se estabilizarán los envíos de petróleos a la isla y los pagos de los servicios médicos cubanos.

Por otra parte, se proyecta un incremento del gasto público y del déficit fiscal para respaldar el aumento del PIB. Se proyecta un aumento de 11 por ciento en los gastos fiscales, pero que no podrá ser cubierto por los ingresos fiscales, por lo que generará un “hueco fiscal” de 11.500 millones de pesos en el año 2017, lo que representa un valor equivalente a 12 por ciento del PIB.

En términos porcentuales es el déficit fiscal más alto desde 1993; en valores más que duplica el déficit del año 1993 que fue de 5.000 millones de pesos.

Es propicio que después de años de austeridad fiscal el gobierno decida expandir el gasto público para amortiguar el efecto recesivo de la crisis venezolana. Es válido aplicar una política fiscal expansiva en momentos de caída del PIB.

También es atinado financiar el déficit fiscal con emisión de bonos públicos, lo cuales comprarán los bancos estatales cubanos. Este es un nuevo instrumento que desde hace dos años viene estrenando el Ministerio de Finanzas y Precios con vistas a evitar la monetización (impresión de nuevo dinero) como mecanismo de financiación del déficit fiscal.

Tal mecanismo de financiación fiscal tiende a acercarse a las prácticas internacionales, y tiene como principal ventaja que evita un incremento de la cantidad primaria de dinero, con lo cual reduce las presiones inflacionarias.

¿Dónde están los riesgos de la política fiscal expansiva y la emisión de bonos?

Primero, el déficit fiscal puede crecer en épocas de crisis, pero no debe hacerlo de manera desmesurada ni mantenerse alto indefinidamente. Está bien aplicar una política fiscal anticíclica, pero tener un hueco fiscal de 12 por ciento del PIB en 2017 trae dudas sobre la sostenibilidad financiera de todo el mecanismo de financiación que se está poniendo en práctica. Para tener un punto de comparación, se espera que los países conserven, en promedio de varios años, un déficit fiscal menor de tres por ciento del PIB.

Se debe tomar en cuenta que los propios inversionistas extranjeros, prestamistas y proveedores internacionales, serán los primeros que estarán mirando este indicador de equilibrio fiscal. A nivel internacional este es uno de los principales indicadores que se toman en cuenta para evaluar la prudencia de la política económica y que define el riesgo financiero del país.

Segundo, la emisión de bonos públicos reduce los efectos inflacionarios pero no los elimina del todo. Expandir el gasto fiscal en 11.500 millones de pesos por encima de los ingresos sí puede presionar al aumento de los precios dada la ampliación desproporcionada que está activando en la demanda de bienes y servicios.

Tercero, Cuba no cuenta con una regla fiscal que organice y ponga límites al equilibrio fiscal de largo plazo (como tienen otros países en la región), sino que depende de la discrecionalidad del gobierno cada año. Es decir, no sabemos qué va a suceder con los déficits fiscales en el futuro. No tenemos seguridad de que los bonos que se están emitiendo y los próximos que se emitirán serán manejados adecuadamente con el fin de garantizar la sostenibilidad de todo el mecanismo.

Se debe tomar en cuenta que los bancos están empleando los ahorros de las familias para comprar los bonos públicos, por tanto, el gobierno tiene la responsabilidad de obtener ingresos fiscales futuros y equilibrar las cuentas públicas para cumplir sus compromisos con los bancos y, en última instancia, con los ahorradores.

Para tener una idea de la magnitud del déficit y de la emisión resultante de bonos públicos, observemos que en el año 2015 el ahorro de las familias en los bancos sumaba 23.680 millones de pesos cubanos.

Por ende, el déficit fiscal presupuestado para el año 2017 equivale a 48 por ciento del valor de las cuentas de ahorros de las familias. Los bancos, ciertamente tienen también depósitos de las empresas y su propio capital. Aun así, esta proporción de 48 por ciento llama la atención sobre el poco espacio de financiación que a futuro tendría el MFP para soportar elevados déficits fiscales.

En resumen, el crecimiento proyectado de dos por ciento para el año 2017 en la economía cubana depende de una situación que sigue siendo incierta para la economía venezolana, a pesar del aumento del precio del petróleo. Además, viene acompañado de una política fiscal expansiva que de ser bien empleada puede ayudar a manejar la crisis, pero en caso contrario, tendría consecuencias desastrosas para la estabilidad monetaria y financiera del país.

La activación de una política fiscal anticíclica y la emisión de bonos públicos es acertada, pero parece exagerado un déficit fiscal que equivale a 12 por ciento del PIB y a 48 por ciento del ahorro de las familias en los bancos.

No habría posibilidades de repetir la expansión fiscal en el año 2018, más bien será indispensable realizar un ajuste fiscal que disminuya significativamente el déficit en los próximos años.

Por tanto, el gobierno solo está ganando un año de tiempo, en el cual deberá aplicar algunas de las reformas estructurales pendientes y necesarias para sacar en firme a la economía de la recesión.

Pavel Vidal

Pavel Vidal