By Arch Ritter

September 6, 2016

Cuban nickel production and the Sherritt-Cuba joint venture should have good prospects in view of Cuba’s large and low-cost reserves of nickel. Sherritt’s technology and probable future demand. However, there are a number of looming issues that darken the horizon for Sherritt and to a lesser extent for Cuba including high transportation costs – shipping nickel/cobalt concentrate from Cuba to Fort Saskatchewan Alberta – together with the “Helms-Burton” status of the mine, and future price levels and volatility..

The Moa mine and processing facility, with a 25,000 ton capacity, were initially constructed by US interests – the Moa Bay Mining Company, a subsidiary of Freeport Sulphur. They used proprietary technology from Sherritt, which had pioneered hydrometallurgy processes at their plant in Fort Saskatchewan Alberta. Extraction and processing began in 1959.

The Government of Cuba then expropriated the operation without compensation in August, 1960 and restarted it in 1961 producing concentrate for the Soviet Union. The US Foreign Claims Settlement Commission (US FCSC) valued the company at US$ 88.4 million at the time of the expropriation.

Sherritt’s direct connection with Cuba began in 1991 with purchases of Cuban nickel concentrate for its Alberta refinery. Sherritt had had insufficient volumes of concentrate for many years and in 1990 a refining contract with INCO expired. In 1994, Sherritt International and the Compania General de Niquel of Cuba established a 50/50 joint venture, which now owns the Moa extraction, processing, and smelting operation, the Alberta refinery and the international marketing enterprise. The former President of the company, Ian Delaney, also negotiated agreements with the Cuban Government, permitting Sherritt to enter other sectors of the economy, including electric energy, oil and gas, agriculture, tourism, transportation, communications, and real estate. By 2000, Sherritt International had become a major diversified conglomerate in Cuba.

In this deal, the Cuban Government became and is currently a foreign investor in Canada, as the Compania General de Niquel owns 50% of the nickel refinery, a fact not well known in either Cuba or Canada.

The joint venture between Sherritt International and the Government Cuba is a cooperative masterpiece. It has generated great benefits for both parties.

I. The Nickel/Cobalt Operation

The linking of the Moa nickel deposit and part of Cuba’s processing capacity with the Alberta refinery and its access to attractive energy sources was a stroke of genius and/or good luck for Sherritt and Cuba.

Cuba acquired a market for its nickel concentrate. It acquired access to the technological improvements that have occurred from 1959 to 2016. These have generated improvements in productivity, energy efficiency, environmental impacts, and health and safety. It acquired Sherritt’s managerial know-how which. Together with technological improvements, have increased production from around 12,500 tons in the early 1990s to around 34,000 tons in the 2010s. The Government of Cuba is now the joint owner of a vertically integrated nickel operation, from extraction and concentrating through to refining and international marketing. Cuba also has obtained new technologies and managerial skills for oil and gas extraction and utilization, as well as electricity generation. Cuba’s nickel reserves are fifth largest in the world and production volumes are 10th largest.[i] Nickel has been Cuba’s largest merchandise export since the collapse of sugar by 2002. Foreign exchange earnings from the Sherritt-Cuba joint venture’s share of nickel and cobalt exports have averaged about 40% of total nickel/cobalt exports.

The Government of Cuba is now the joint owner of a vertically integrated nickel operation, from extraction and concentrating through to refining and international marketing. Cuba also has obtained new technologies and managerial skills for oil and gas extraction and utilization, as well as electricity generation. Cuba’s nickel reserves are fifth largest in the world and production volumes are 10th largest.[i] Nickel has been Cuba’s largest merchandise export since the collapse of sugar by 2002. Foreign exchange earnings from the Sherritt-Cuba joint venture’s share of nickel and cobalt exports have averaged about 40% of total nickel/cobalt exports.

It is not surprising that Ian Delaney became known as “Fidel’s Favorite Capitalist”!

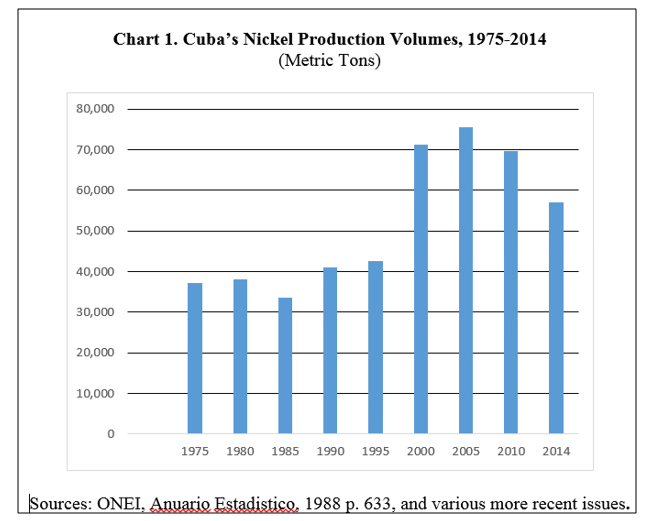

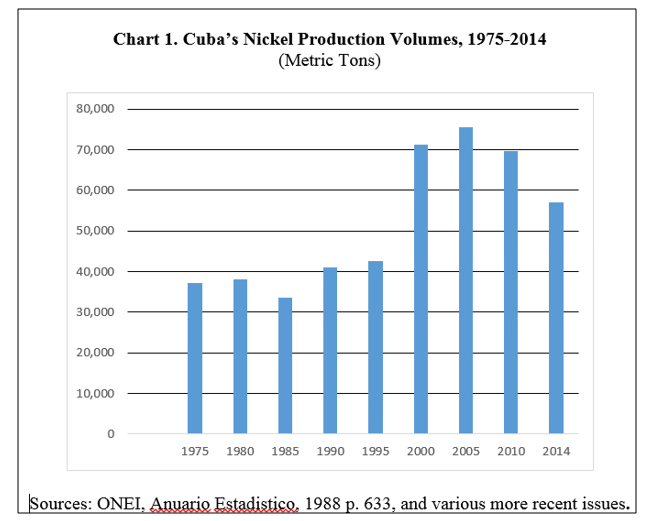

For its part, Sherritt has been able to maintain its Canadian refinery and to use its base in nickel to enter other sectors in Cuba. Its earnings from its Cuban operations are significant. The joint venture has been able to increase metal production and achieve high net operating earnings, which have been in the area of 40 to 50 percent of the company’s gross revenues for most years, depending on international nickel prices. The following chart illustrates Cuba’s total nickel production volumes. The impact of Sherritt’s innovations in increasing production volumes in the second half of the 1990s is apparent.

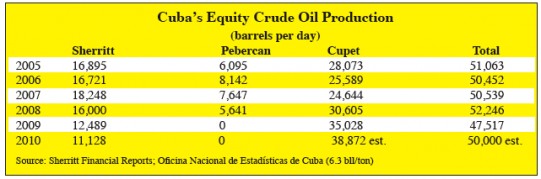

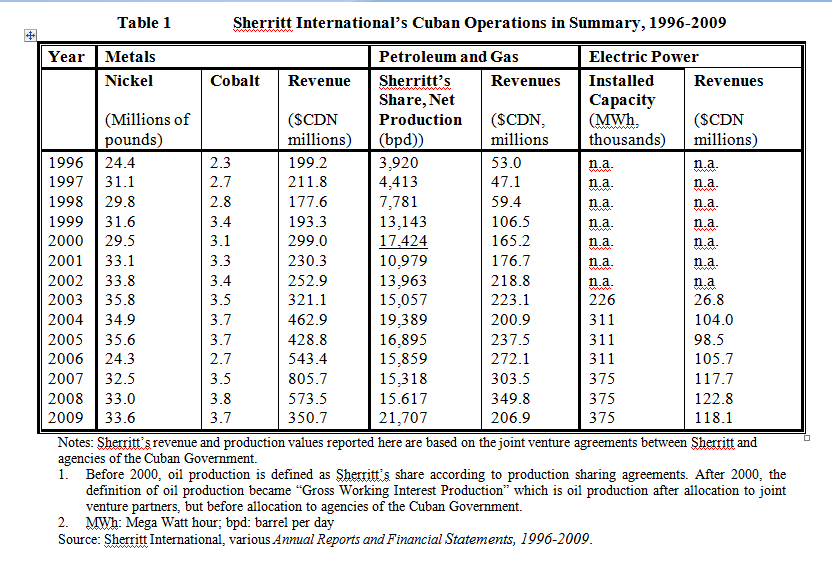

II. Petroleum, Natural Gas and Electric Power

Sherritt International’s petroleum and natural gas activities also have been successful. New sources of oil and gas have been discovered and extraction rates have increased through enhanced recovery techniques from 1996 to 2000. Natural gas recovery and utilization has also been improved through the construction of two processing plants, a feeder pipeline network, and a 30 Kilometer pipeline to Havana (Sherritt International, Annual Report, 1997, 13).

Sherritt invested CDN $215 million for the construction of two integrated gas processing and electrical generation systems. The natural gas feedstock previously had been flared and wasted. Commissioned in mid-2002, these operations had a combined capacity of 226 megawatts and generated a significant proportion of Cuba’s electricity. At the same time they reduced sulfur emissions, a potential problem especially at the Varadero site, which is adjacent to the hotel zone. By 2007, installed electricity generation capacity had been further increased to 375 mega watts, following an 85 MW expansion that came on stream in early 2006.

In February 1998, Sherritt acquired a 37.5 percent share of Cubacel, the cellular telephone operator in Cuba for $US 38 million, but this was resold. “Sherritt Green,” a small agricultural branch of the company, entered market gardening, cultivating a variety of vegetables for the tourist market. Sherritt also acquired a 25 percent share of the Las Americas Hotel and golf course in Varadero and a 12.5 percent share of the Melia Habana Hotel, both of which were managed by the Sol Melia enterprise but these also have been divested. By 2010, Sherritt’s Cuban operations were large and growing. Gross revenues reached CDN $1,040 million in 2008.

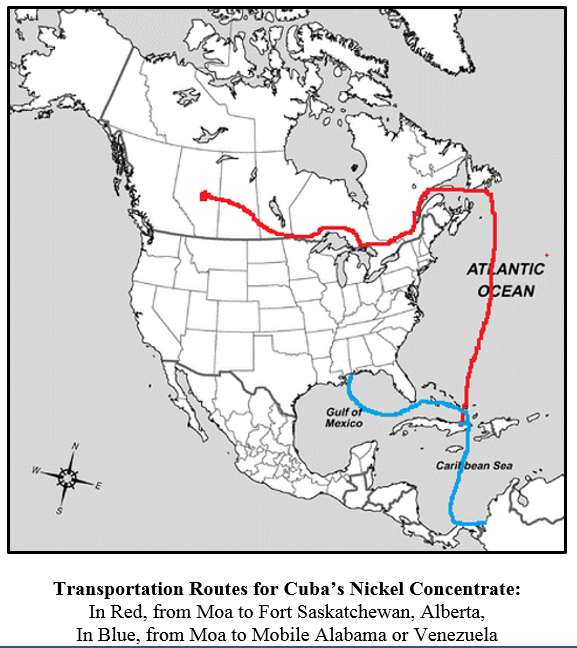

III. Energy Costs, Transport Costs and Potential Relocation

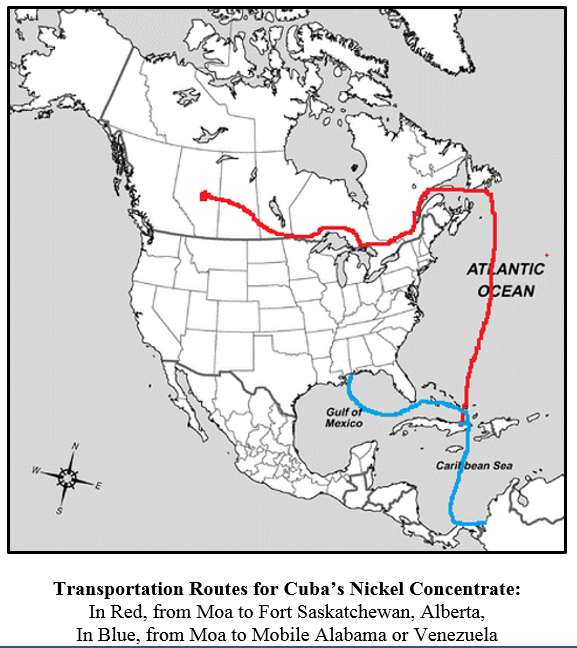

However, there are a number of clouds on the horizon for Sherritt. First, Cuban nickel concentrate is transported by ship to the east coast of Canada and then overland to the Alberta refinery. This makes some sense economically when energy prices are low. So far, the existence of the refinery there has compensated for high transportation costs. However, if – or when –transportation costs rise with higher energy prices or when full normalization with the United States occurs or when the existing plant reaches the end of its useful life, would a different location become more attractive? Energy sources are also available in Venezuela as well as the Gulf of Mexico region of the United States or could be transported to Cuba itself in future. At some point it will likely make sense to relocate a refinery to a locale closer to the nickel ore body.

So far, Cuba is tied to the Canadian location through its 50% joint ownership of the Alberta refinery. But would Sherritt relocate the refinery to a lower-risk Cuba at some time in the future, or to the post-embargo United States or a post-Maduro Venezuela? Perhaps. However, Alberta will continue to have competitive energy prices and low risk to compensate for its locational disadvantage for some years to come.

IV. “Helms-Burton” Status of the Mine Properties.

The second possible problem for Sherritt is that the Moa mine and the concentration plant are “Helms-Burton” properties for which there are US claimants. What would be the current value of the Using the US FCSC interest rate of 6% per year of non-payment, the 2016 compounded value would be a whopping US$ 2,054.6 million. Obviously there will be a negotiations problem for this and all other such claims.

Resolution of the compensation claims issue with full US-Cuba normalization may require Sherritt and the Government of Cuba to negotiate some sort of compensation package for the original US owners. In one scenario, the US claimants would simply take over the Cuba-Sherritt operation in Cuba. But this would not be reasonable because at this time, the refinery for Cuban nickel is in Alberta and it is jointly owned by Cuba. My guess, however, is that Sherritt, the Government of Cuba and the US claimants will negotiate an arrangement that will be reasonable for all parties.

In any case, the claim of US interests on the mine property generates ambiguities and uncertainties and will be problematic at some time in the future. Sherritt International may well be one of the few economic interests that perhaps could lose from US-Cuban complete economic normalization. A resolution of the property claims issue may turn out to be very expensive for Sherritt. .

V. “Nickel Pig Iron”

A technological advance in the production of “Nickel Pig iron” (NPI), a substitute for refined nickel-steel alloys for some uses where high quality is less necessary. “Nickel pig iron” may well have already captured a portion of the nickel market for low quality alloys. In future, it may reduce the demand for nickel thereby placing downward pressures on nickel prices. This will likely reduce and Cuba’s foreign exchange earnings and Sherritt’s revenues and profits from nickel exports in future.

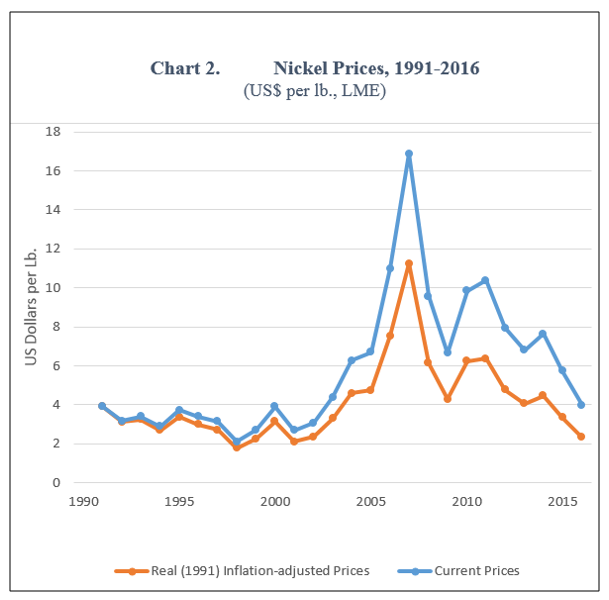

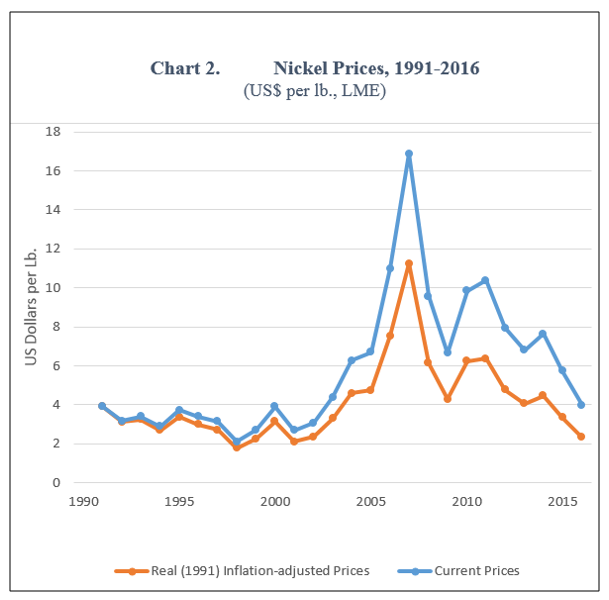

As illustrated in Chart 2, nickel prices spiked in the boom of 2003-2007 – helping to generate a period of relative prosperity for Cuba – then declined in the recession of 2008. What is striking at this time is that in real inflation adjusted terms, the price of nickel in 2015 and 2016 is pretty much where it was in the 1990s. A number of factors are contributing to this of course, especially the growth rate deceleration in China reducing the demand for nickel. Is “nickel pig iron” also contributing to weak demand for nickel at this time? What will be its impact in future?

Source: United States Geological Survey, Minerals Information, Nickel: Statistics and information., various years. The “real” or “inflation adjusted” price is the US consumer price deflator.

In conclusion, Sherritt has had a great run in Cuba, contributing to improved nickel production and exports, higher foreign exchange earnings for Cuba and high revenues and profits for itself, especially in the 2004-2014 decade. The future may be less brilliant for both with the uncertainties of resolving the property claims issue and a possible slow=down in international demand for nickel generated in part by “nickel pig iron.”

The Government of Cuba is now the joint owner of a vertically integrated nickel operation, from extraction and concentrating through to refining and international marketing. Cuba also has obtained new technologies and managerial skills for oil and gas extraction and utilization, as well as electricity generation. Cuba’s nickel reserves are fifth largest in the world and production volumes are 10th largest.

The Government of Cuba is now the joint owner of a vertically integrated nickel operation, from extraction and concentrating through to refining and international marketing. Cuba also has obtained new technologies and managerial skills for oil and gas extraction and utilization, as well as electricity generation. Cuba’s nickel reserves are fifth largest in the world and production volumes are 10th largest.