CubaDebate, 12 julio 2015 | 34

Original Article here : http://www.cubadebate.cu/opinion/vision-externa

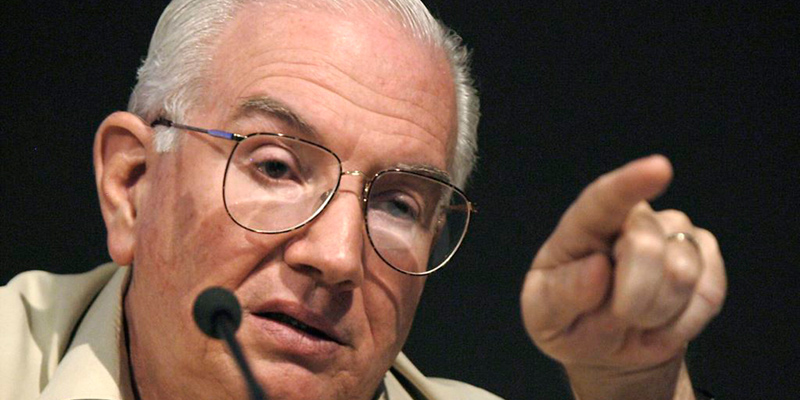

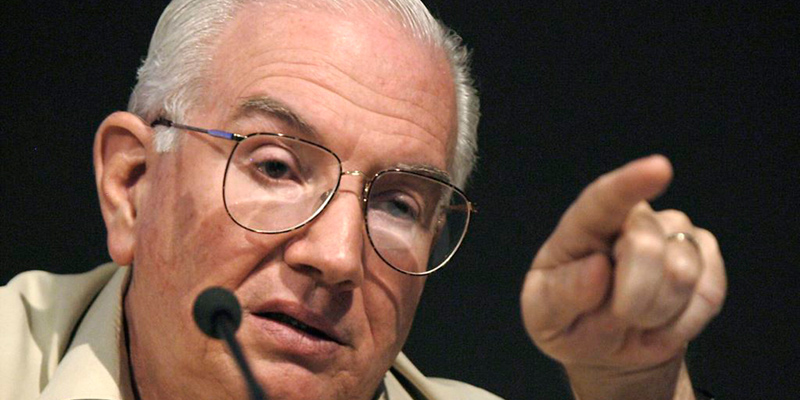

José Luis Rodríguez es asesor del Centro de Investigaciones de la Economía Mundial (CIEM). Fue Ministro de Economía de Cuba.

Algo que sin dudas ha llamado la atención a lo largo de la historia de la Revolución es la proliferación de múltiples interpretaciones externas sobre lo que se hace en el país, especialmente en el orden de la política económica. Desafortunadamente, la cantidad no hace la calidad y muchos de los trabajos que se han publicado adolecen de un mínimo de rigor analítico en sus análisis, en especial, aquellos que parten de una visión anti socialista excluyente de otro modelo que no sea afín a la economía de mercado en las diferentes versiones de la misma.

En el presente artículo no se pretende realizar un balance exhaustivo de todos estos enfoques, ni siquiera de aquellos que se han producido a lo largo de los últimos cinco años y que se relacionan con la actualización del modelo económico en curso. No obstante, resulta útil destacar algunas tendencias presentes en el ámbito académico y que permiten identificar los principales enfoques acerca de las transformaciones económicas que se desarrollan en Cuba en la actualidad.

Lo primero que valdría la pena subrayar es que no se aprecia una ruptura con paradigmas anteriores que han preponderado a la hora de examinar la realidad económica en Cuba a lo largo de los años. Ello se aprecia en los análisis que se llevan a cabo por la Asociación para el Estudio de la Economía Cubana (ASCE) de Estados Unidos, que se reúne sistemáticamente todos los años desde 1990 y que publica la memoria de sus debates en los que continúa siendo mayoritaria una visión cercana al neoliberalismo más ortodoxo y al mainstream de la cubanología tradicional al evaluar nuestra realidad.

En este sentido destacan –como ejemplo- los numerosos artículos de Luis R. Luis, uno de los editores del blog de ASCE, que se empeña en pintar con los tonos más oscuros posibles la realidad económica en Cuba calificándola como economía arruinada y carente de liquidez internacional, lo cual se aprecia en sus recientes artículos “Cuba’s Feeble International Liquidity” (La débil liquidez internacional de Cuba) publicado en el blog de ASCE el 9 de abril y “Cuba-US Reconciliation and Limited Reforms” (Reconciliación Cuba-EEUU y reformas limitadas) publicado el 22 de mayo pasado. En ambos trabajos se constata la ausencia de un análisis objetivo, que no excluya otros enfoques desarrollados por la academia en los propios EEUU, y que no ignore informaciones oficiales del gobierno cubano tales como el discurso del Ministro de Economía y Planificación Marino Murillo, pronunciado en la Asamblea Nacional en diciembre de 2014, donde se brindan numerosas informaciones sobre la política de financiamiento externo del país, entre otros temas de importancia para el análisis.[1]

Afortunadamente, se pueden encontrar otros enfoques no necesariamente afines a las ideas socialistas, pero que elaboran sus tesis con una mayor seriedad y rigor, aun en el terreno en el que necesariamente se mantienen discrepancias de fondo con los economistas que defendemos la Revolución.

Si se examinan los años transcurridos desde que se aprobaron los Lineamientos de la Política Económica y Social del país en abril de 2011, se proyecta una valoración crítica de las medidas propuestas en diversos trabajos del profesor Carmelo Mesa-Lago tal y como aparecen en su libro “Cuba en la era de Raúl Castro. Reformas económico-sociales y sus efectos” (Editorial Colibrí, Madrid, 2012), que reseñé en la revista TEMAS Nº 73 de 2013. Su valoración resumió diversos argumentos basados en una ideología keynesiana que sustentaba el análisis de errores que en su opinión llevaban a la inviabilidad del socialismo en Cuba.

Con posterioridad al 17 de diciembre de 2014, Mesa-Lago se ha pronunciado sobre los cambios en Cuba, incluyendo la perspectiva que se abre en las relaciones con Estados Unidos. En un reciente trabajo titulado “Normalización de las relaciones entre EEUU y Cuba: causas, prioridades, progresos, obstáculos, efectos y peligros” (Real Instituto El Cano, Documento de Trabajo Nº 6/2015, 8 de mayo de 2015 disponible en www.blog.rielcano.org ) el profesor Mesa-Lago realiza un interesante análisis de la nueva situación y ofrece una visión notablemente objetiva de muchos temas que atañen a la evaluación de los cambios en Cuba, lo cual resulta destacable en relación a otros trabajos anteriores. No obstante, el documento tiene un enfoque negativo sobre las relaciones de Cuba con Venezuela tomando como válidas informaciones y datos que resultan especulativos, especialmente cuando valora el supuesto impacto sobre la economía cubana de una contracción económica en Venezuela este año y ubica la situación de ese país como un motivo para buscar el acercamiento de Cuba con Estados Unidos, lo cual no se corresponde con la verdad.

Igualmente el documento cierra con lo que el autor denomina como el enigma de la posición cubana frente al proceso de negociación con Estados Unidos, el cual revela un alto grado de especulación y desconocimiento de las razones que asisten a Cuba para fundamentar sus posiciones. A pesar de estos aspectos controversiales, el documento revela un análisis profundo y abarcador de las relaciones posibles entre Cuba y Estados Unidos por parte del autor, que revela el fruto de un trabajo sistemático y serio sobre estos temas durante muchos años.[2]

II

Un aspecto que es tomado como premisa en el análisis de las transformaciones más recientes de la economía cubana por la mayoría de los autores, es el fracaso del modelo socialista de desarrollo y lo inevitable de la transición a una economía de mercado.

Al respecto se destacan investigadores como Richard E. Feinberg, ex funcionario del gobierno norteamericano, actual profesor de la Universidad de California en San Diego y Senior Fellow de Brookings Institution, uno de los principales tanques pensantes de Estados Unidos. Este analista ha venido publicando sistemáticamente trabajos sobre la economía cubana, entre los que se destacan sus ensayos “Extendiendo la mano: La nueva economía de Cuba y la respuesta internacional” Iniciativa para América Latina, Brookings Institution, Washington, noviembre de 2011, www.brookings.edu y “¿Aterrizaje suave en Cuba? Empresarios emergentes y clases medias” Iniciativa para América Latina, Brookings Institution, Washington, noviembre 8 de 2013, www.brookings.edu.

En el primero de estos trabajos Feinberg defiende la tesis de que constituye una anomalía la no pertenencia de Cuba a organismos financieros internacionales como el FMI y el Banco Mundial, por lo que propone un programa de aproximaciones sucesivas para superar esa situación, tomando como ejemplo los casos de Nicaragua y Vietnam para ello. Sin embargo, esta propuesta no parte de aceptar los cambios que Cuba se planteó en los Lineamientos de la Política Económica y Social, sobre los que el autor expresa que “Las pautas están plagadas de contradicciones internas y siguen rindiendo culto a la planificación centralizada, pero las fracciones pro reforma fueron lo suficientemente fuertes para incluir un lenguaje que transformaría la cultura política y la ética social cubana si se lo interpretara y actuara en consecuencia.”

Claramente sale a relucir que la transición al capitalismo es a fin de cuentas lo determinante y para ello se cifran esperanzas en lo que Feinberg denomina como “las fracciones pro reforma”.

Adicionalmente faltaría por demostrar que es posible ingresar al FMI y sostener un programa de desarrollo como al que Cuba aspira, especialmente si se tiene en cuenta el papel que ha jugado este organismo en la aplicación de las recetas neoliberales a toda costa, tal y como se refleja en estos momentos en su posición frente al actual gobierno de Grecia en la Unión Europea.

Acerca de este supuesto papel positivo del FMI, bastaría con examinar su desempeño en la transición al capitalismo en Europa Oriental y la antigua URSS, cuestión abordada muy seriamente por la investigadora del Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo Emily Morris en el artículo “Unexpected Cuba” publicado en New Left Review Nº 88, Julio-Agosto 2014 www.newleftreview.org [3].

Un analista que trabaja los temas de la economía cubana desde la década de los años 70 del pasado siglo es el profesor de la Universidad de Carleton Archibald Ritter. Autor de uno de los pocos libros sobre la estrategia de desarrollo de Cuba –“The Economic d=Development of Revolutionary Cuba: Strategy and Performance”, Praeger, New York, 1974- ha incursionado con una visión crítica en distintos aspectos del desempeño económico del país, dedicándole especial atención en los últimos años al desarrollo del sector privado. En este sentido Ritter publicó junto a Ted Henken el libro “Entreprenurial Cuba: The Changing Policy Landscape” que vio la luz en 2014[2], trabajo que aborda desde diferentes ángulos la temática del llamado sector no estatal.

Al igual que otros textos, en este libro se examinan las insuficiencias para el desarrollo sin límites de la propiedad privada y cooperativa, por lo que se deja establecido que solo en una economía de mercado pueden evaluarse sus verdaderas potencialidades, con lo que evidentemente se niega la posibilidad de su desarrollo en los límites que supone una economía socialista.

Finalmente vale la pena destacar otro trabajo que –previo al escenario actual de posibles relaciones con Estados Unidos- se elaboró anteriormente. Este es el caso del ensayo de Gary Clyde Hufbauer, Barbara Kotschwar y Cathleen Cimino “Economic Normalization with Cuba. A Roadmap for US Policymakers” Policy Analysis Nº 103, Peterson Institute for International Economy, 2014 www.piie.com . Siguiendo la línea de otros autores, en este análisis se propone para Cuba un modelo de transición a una economía de mercado siguiendo el modelo de Europa Oriental a través de diferentes pasos, que incluyen la apertura del mercado de Estados Unidos y el ingreso a los organismos del sistema financiero internacional, es decir, al FMI, Banco Mundial y Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo.

III

Otros análisis de interés sobre la economía cubana en años recientes, que no toman como premisa una transición inevitable a la economía de mercado en nuestro caso, también puede encontrarse en diferentes autores, sin que se pretenda en este breve artículo hacer un listado exhaustivo de los mismos.

Profundo conocedor de la economía cubana a la que ha estudiado durante muchos años, el economista sueco Claes Brundenius, actualmente Profesor Honorario del Research Policy Institute de la Universidad de Lund, elaboró uno de los libros más importantes sobre el desarrollo socioeconómico en Cuba: “Revolutionary Cuba: The Challenge of Economic Growth with Equity” (Cuba revolucionaria: el desafío del crecimiento económico con equidad) Westview Press, Boulder, 1984, al que siguieron numerosos artículos y libros de especial valor –varios de ellos elaborados en esos años con el destacado profesor Andrew Zimbalist del Smith College. Entre los trabajos más significativos se destaca “Revolutionary Cuba at 50: Growth with Equity Revisited” (Cuba revolucionaria a los 50: crecimiento con equidad revisados) Latin American Perspectives Volume 36, Nº 2, March 2009.

En uno de sus libros más recientes, coeditado con Ricardo Torres: “No More Free Lunch. Reflections on the Cuban Economic Reform Process and Challenges for Transformation” (No más comida gratis. Reflexiones sobre el proceso cubano de reformas y desafíos para la transformación) Springer, London, 2014; Brundenius ofrece una evaluación sobre los cambios en Cuba y las reformas económicas en Vietnam. Sin dejar de plantear ideas que pueden resultar polémicas, Brundenius arriba –como en trabajos anteriores- a conclusiones más objetivas y balanceadas al afirmar en este libro “Es un poco irónico que mientras nosotros hablamos sobe la crisis del modelo socialista en Cuba, el capitalismo en todo el mundo atraviesa su crisis más profunda desde la Gran Depresión (…) Pero claramente, el capitalismo no es “el fin de la historia” y es ahora más que nunca importante buscar modelos alternativos que puedan combinar la eficiencia de la competitividad de los modelos de mercado con sostenibilidad ambiental combinada con equidad, solidaridad y democracia. Modelos cooperativos pueden ser una importante parte de esas soluciones como se discuten en este volumen.”

Además de Emily Morris ya mencionada anteriormente, un grupo de diversos autores se han destacado por aportes puntuales al análisis socioeconómico de la realidad cubana desde posiciones igualmente objetivas y no prejuiciadas de nuestra realidad.

Entre ellos vale la pena destacar la labor de Albert Campbell, Profesor de Mérito de la Universidad de Utah, que durante años ha emprendido estudios sobre Cuba en el campo de la economía política y la filosofía de indudable relevancia y que fue el editor del más reciente libro publicado en Estados Unidos escrito totalmente por autores cubanos residentes en nuestro país: “Cuban Economist on the Cuban Economy” (Economistas cubanos sobre la economía cubana) The University Press of Florida, Gainesville, 2013.[4]

En este grupo pueden incluirse con diversos matices, los británicos George Lambie –uno de los editores del International Journal of Cuban Studies, del International Institute for the Study of Cuba- y Mervyn Bein, especialista en temas de relaciones entre Cuba y los antiguos países socialistas; el canadiense John Kirk, durante muchos años estudioso de la colaboración internacional brindada por Cuba en el campo de la salud y editor de la colección Contemporary Cuba de la University Press of Florida; los académicos norteamericanos Nelson Valdés Profesor Emérito de Sociología en la Universidad de Nuevo México profundo conocedor de la realidad cubana, creador de uno de los proyectos de investigación más completo sobre Cuba contemporánea –Cuba-L Direct-; Frank Thompson, profesor de la Universidad de Michigan; Paolo Spadoni, profesor asistente de Georgia Regents University y autor del libro “Cuba’s Socialist Economy Today. Navigating Challenges and Change” (La economía de Cuba socialista hoy. Desafíos de la navegación y cambio) Lynne Rienner, Boulder, 2014, libro en el que se realiza un análisis macroeconómico –no exento de criterios debatibles pero interesantes- acerca de las transformaciones en desarrollo actualmente en Cuba; y Jorge R. Piñón un destacado especialista en temas energéticos y director de Latin America and Caribbean Energy Program en la Universidad de Texas en Austin.

Lógicamente, con posterioridad al 17 de diciembre de 2014 el tema de Cuba y su economía ha pasado a ocupar un destacado lugar en todos los análisis, tanto por los especialistas, como por aquellos que comienzan a enfrentarse al estudio de nuestro país.

Un examen sobre estas nuevas visiones y las diferentes teorías que se enarbolan para sustentarlos, merecerá una evaluación más detenida en la misma medida en que se vayan despejando obstáculos que –como la permanencia del bloqueo norteamericano contra Cuba- no permiten una proyección clara de los posibles derroteros de las relaciones económicas entre nuestros dos países a corto plazo.

Por el momento, resulta de mucha importancia para los economistas cubanos mantener un seguimiento de todos los trabajos que se publican en el exterior, especialmente de aquellos académicos que han demostrado una mayor rigurosidad en sus análisis hasta el presente, tomando en cuenta su posible contribución al debate científico y a profundizar en el desarrollo de los estudios sobre la economía cubana.

Notas

[1] En esta misma línea de pensamiento se incluyen autores como Jorge Sanguinetty, Roger Betancourt, Rolando Castañeda, Joaquín J. Pujol y Ernesto Hernández-Catá todos ponentes regulares de “Cuba in Transition” el anuario que publica la ASCE desde 1990. Ver www.ascecuba.org

[2] En este trabajo no solamente se contrastan críticamente los elementos esenciales de la política económica cubana con la aplicada en los ex países socialistas europeos, sino que se incluye una valoración crítica de los enfoques de la cubanología al respecto, lo cual es un valor añadido muy interesante para el análisis.

[3] Hay una versión disponible en español. Ver “Emily Morris: Cuba ha demostrado que la economía socialista es posible” Cubadebate, noviembre 24 de 2014 en www.cubadebate.cu

[4]La introducción a este libro se encuentra en www.thecubaneconomy.com