The Economist, December 18, 2015

Original Essay: Cuban Baseball Crisis

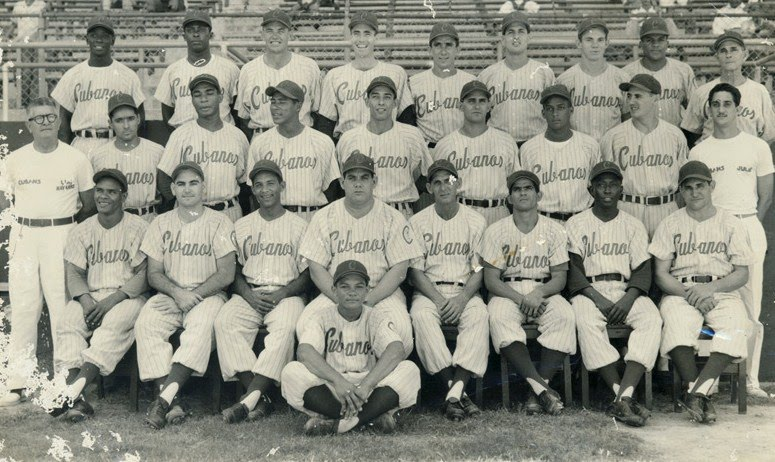

The Havana Sugar Kings of the old International League, circa 1956

The Havana Sugar Kings of the old International League, circa 1956

LOOK for the Che Guevara mural on a pitch-black street corner in Lawton, a run-down district on the outskirts of Havana. Turn left, walk up the concrete steps and give the password (today it’s “I sell green dwarfs”). Inside, around 20 Cuban men sit silently. Despite the humidity, the ceiling fan is still, allowing puffs of sweet tobacco smoke to hover in the flickering fluorescent light. The newcomers are asked for a “solidarity contribution” of 25 Cuban pesos, or $1. After the customary first drops are spilled to sate the thirst of the saints, a $3 bottle of clear rum makes its way around.

It could easily be a clandestine political gathering. But this group has far more important business: the first game in the Major League Baseball (MLB) semi-final series between the Kansas City Royals and Toronto Blue Jays. For half a century after Cuba’s revolution in 1959, the island’s sports fans knew little of professional leagues beyond their shores. But today, thanks to the internet’s belated arrival and a wave of Cuban players defecting and starring in MLB, in-depth knowledge of American baseball is a badge of honour for baseball-loving Cubans—that is, nearly all the men and plenty of the women, too. “You didn’t know Kansas City won? You’re an embarrassment,” one attendee teased a friend during the ride to Lawton in an exhaust-spewing 1950s taxi, whose shock absorbers were no match for the area’s cavernous potholes.

The easiest way for Cubans to follow MLB in real time is at hotel bars in Vedado, a central Havana district packed with middle-aged American tourists taking advantage of the recent relaxation of travel restrictions. But few Cubans can afford a beer priced in dollars. And if a woman happens to be running a shift at the bar, locals say, there’s always a risk she will put a soap opera on the TV instead. So baseball fans gather in speakeasies like this decrepit flat, whose owner has managed to acquire an illegal satellite broadcast signal and hook it up to his 1980s Japanese television.

The group try to keep quiet, lest the neighbours snitch to the local Committee for the Defence of the Revolution (a network of government informants in every town). But they are rooting for the Royals because of the team’s first baseman, Kendrys Morales, who fled Cuba on a raft in 2004 after serving several stints in jail for his seven previous failed escape attempts. Every time he comes up to bat they allow themselves a muffled cheer. A round of high-fives follows Kansas City’s 5-0 victory.

The next day a big game is scheduled in the domestic baseball league, at Havana’s rickety 55,000-seat Latin American Stadium. It pits the hometown Industriales, Cuba’s answer to the New York Yankees, against a visiting club from nearby Matanzas. A few years ago the stands would have been packed. But today the outfield bleachers are empty, and only the rows of seats closest to the action appear even half-full. Bored-looking police drag on cigarettes. A group of hometown fans tries to rouse the crowd by blaring on hand-held air horns, but it is well short of critical mass.

One reason for the apathetic mood is that the government has banned alcohol sales in stadiums to stop fights. A bigger problem is the poor quality of the play. Last year 11 Industriales players left for the United States; Matanzas lost ten. Only the weaker players remain, and they are demoralised: runners seem content to jog around the basepaths, and fielders let the ball skip past them on difficult plays. In recognition of the depleted rosters, the Cuban league now disbands half of its teams at mid-season and shares their players among the eight clubs that are doing best.

Today’s game is painfully lopsided, as the Matanzas hitters pound the Industriales starting pitcher for seven runs. The biggest attraction is Rey Ordóñez, who defected in 1993, played in MLB for nine years and is catching a game on a visit home. Fans pose with him for pictures. “It’s very hard for the team,” says Lourdes Gourriel junior, the 21-year-old shortstop for the Industriales, following his team’s defeat. “It’s weird seeing someone on TV [in MLB], and just yesterday they were here with you. But that’s everyone’s individual decision. We’re still friends with those who left.”

South American football fans are accustomed to their countries’ brightest sporting stars decamping to richer European leagues. But for Cuban baseball fans the exodus is new. Less than a year after the United States and the government of Raúl Castro, Fidel’s younger brother and successor, announced they would re-establish diplomatic relations, this brawn drain is the most visible consequence of rapprochement with the yanquis, and an indication of what might be lost as the Cuban economy liberalises.

BOTTOM OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

Although baseball originated in the United States, the sport arrived in Cuba during its infancy in the 1860s. Within a decade of the first recorded match on the island, Cuba had established the first professional league outside America and put its adopted national game at the service of political aims: the league’s organisers funnelled its profits to guerrilla groups fighting for independence from Spain, and the movement’s spies posed as baseball players when shuttling messages and funds to and from supporters in the United States. “Baseball is more Cuba’s national pastime than it is America’s,” says Roberto González Echevarría, the author of a history of Cuban baseball. “It was considered modern, democratic and American, while the Spaniards had bullfighting, which was retrograde and barbaric. It’s as if the American Founding Fathers had been wielding Louisville Sluggers [an iconic brand of bat].”

After Cuba gained its independence in 1902 baseball became one of its principal means of exercising soft power. It was Cuban athletes, not American soldiers, who spread the sport across the Spanish-speaking Caribbean, helping to form a shared cultural identity with the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Venezuela and eastern Mexico, and earning the Cuban players the nickname the “apostles of baseball”. And it was baseball players who became the best-known Cubans in the United States. Of all the MLB players born in Latin America who started playing before 1959, two-thirds were Cuban, even though most of the island’s stars were black and banned from MLB until the league’s colour barrier was broken in 1947. (In 1912, in response to inquiries about the lineage of two olive-skinned Cuban players, the Cincinnati Reds conducted an “investigation” which declared them “two of the purest bars of Castilian soap [that] ever floated to these shores”.) During the same period Cuba was putting black and white talent on the same fields in its racially integrated winter league, establishing the country as an exemplar of moral leadership in sports.

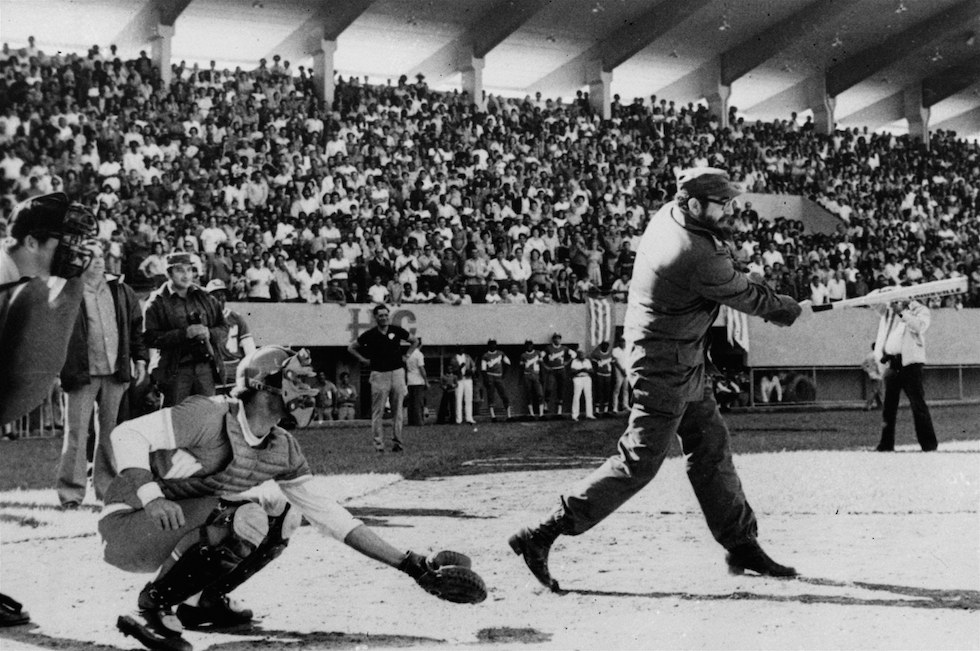

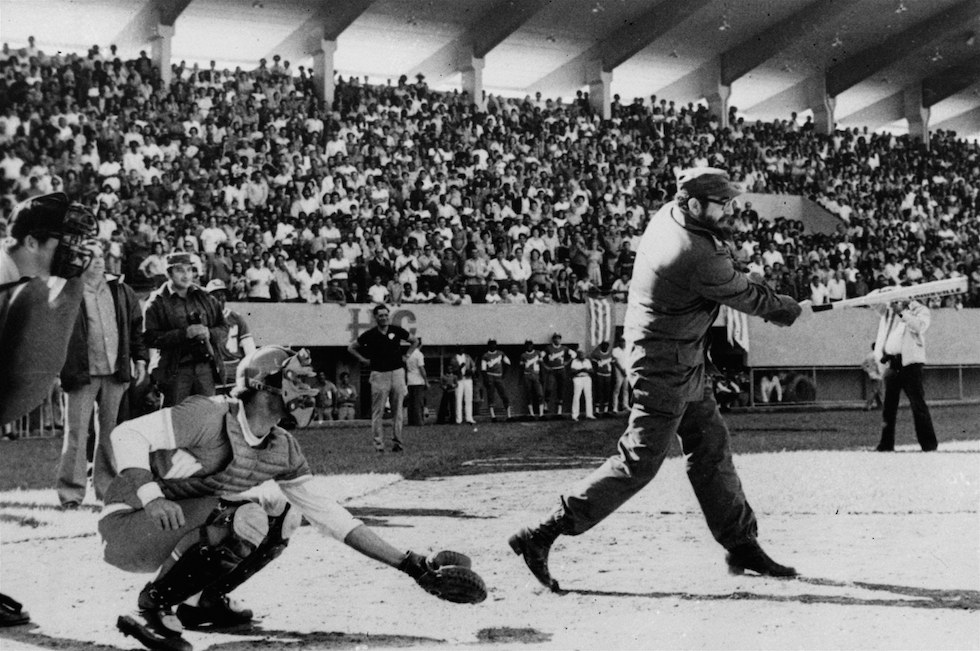

After Fidel Castro (pictured, swinging) took power and became the island’s baseball-fan-in-chief, the sport’s tacit political role became explicit. He proclaimed athletes to be “standard-bearers of the revolution playing for the love of the people, not money”. He banned professional sports and founded the National Series, a wildly popular amateur league in which each province fielded a team of players from its territory. He also established a formidable player-development system, with scouts identifying talented children and academies to train them once they became teenagers.

American fans, who then, as now, paid attention only to MLB, were unaware of the stars Cuba was producing, since they never played for a team in the United States. But Cuba’s athletic assembly line yielded a national team that dominated the weak competition in international events like the Olympics (in which MLB players do not participate): from 1987 to 1997, the squad won 156 straight games. The elder Mr Castro made such successes central to his propaganda strategy. “The only way Cuba could raise its head in the world was in sports,” says Ismael Sené, who ran the sports department of the Communist Youth in the early 1960s. “There was a campaign against us from the outside, saying that we were all needy, that we didn’t have food. Well, look at our athletes!” The fact that baseball, America’s “national pastime”, was Cuba’s strong suit made each victory extra sweet.

Fidel Castro might be proud of Cuba’s ability to export baseball players, were they not going to America

But setting so much store by its baseball players left the government vulnerable to shifting geopolitics. In 1991 René Arocha, a pitcher in the national team, walked out of his hotel room during a tournament in Miami, made his way to his aunt’s house, and never returned, making him the first team member to defect in history. He had not been planning on playing baseball afterwards, because he had assumed that MLB players were far superior to Cuban ones. But after connecting with a Cuban-born agent, he was given an MLB contract with a six-figure salary, and the next year became the St Louis Cardinals’ second-best pitcher.

After Mr Arocha had proved that Cuban players were of MLB quality, and the fall of the Soviet Union plunged Cuba into a “special period” of unprecedented poverty, more defectors began to leak out. Two half-brothers, Liván and Orlando Hernández, left the island separately in the 1990s, one at a tournament, the other on a rickety boat. Both played starring roles for World Series champions in their first years in MLB, providing Miami’s Castro-hating exiles with a remarkable narrative about the risks Cubans will take for a taste of freedom and the chance to play America’s game. To reduce the risk of further defections, the Cuban team put its players under tight surveillance whenever they travelled abroad, making their national treasures feel like prisoners and encouraging more defections.

SQUEEZE PLAY

The government responded to early defections with stoicism. “When one leaves, another ten better players emerge,” Fidel Castro once said. But in the past few years, the trickle of defections has become a torrent. As recently as 2007 there were just ten Cubans in MLB. Today there are 27. And whereas some of the early defectors had undistinguished careers, the current crop is aking an impact that, were it to occur anywhere but in the reviled United States, Fidel Castro would probably regard as his greatest accomplishment. Yoenis Céspedes, a burly outfielder with a pronounced uppercut swing, single-handedly powered the New York Mets to the World Series this year. His deadly accurate throws to home plate from distances of 300 feet (91 metres) or more have earned him the nickname the Cuban Missile. José Fernández, who fished his mother out of the ocean after a wave swept her overboard during their escape to Mexico when he was 15, is the toast of Miami’s Little Havana for his unhittable array of blazing fastballs and knee-bending curves. Aroldis Chapman holds the record for the fastest pitch in MLB history at 105 miles (169km) per hour. At the “Esquina Caliente” (Hot Corner), a bench in a downtown Havana park where die-hard fans have gathered daily for decades to talk baseball, the regulars today come prepared with the latest statistics on how Cuban players—and even the American-born children of Cuban exiles—are performing in MLB. They use websites like CubanPlay, a new, locally run site, by connecting their phones to public hotspots accessible with $2-an-hour Wi-Fi cards.

Major-league success has been accompanied by major-league riches: the 27 Cuban MLB players earn an aggregate annual salary of $100m. As the rewards have grown, a sophisticated infrastructure to smuggle more players has built up. Almost all recent defectors have escaped with the help of sinister human-trafficking syndicates. These hire boats to bring players to nearby countries, bribe the Cuban coastguard to let them depart, and Dominican or Mexican authorities to grant residency papers, pay tribute to organised-crime groups for the right to operate on their turf, and hold players hostage until they sign an MLB contract and provide a return on the gangsters’ investment, perhaps from their signing bonus. Yasiel Puig, a star right fielder, was held at a motel in Mexico’s Yucatán peninsula for months while his captors, associated with the fearsome Zetas mafia, argued over payment. Leonys Martín, an outfielder, was held at gunpoint in Mexico and forced to sign a contract in which he promised to pay 30% of his earnings to a front company; his smugglers are now in a Florida jail.

Since Raúl Castro became Cuba’s president in 2006, he has cautiously tried to relax state controls. But the defections have forced the pace when it comes to baseball. In 2013 Cuba said it would allow athletes to play professionally in foreign leagues—if they paid a 20% tax and returned for international tournaments and the winter National Series. A handful have gone to the Japanese league in the summer and earned seven-figure salaries.

Both MLB and the Cuban government now say they want a “normalised” system, in which Cuban athletes can travel to America legally and safely, play for MLB teams on a work visa and return home in the off-season. Antonio Castro, one of Fidel’s nine acknowledged children, an international baseball official and the national team’s doctor, has publicly called for such a change.

In an echo of the 1970s “ping-pong diplomacy” in which table tennis helped restore relations between the United States and China, MLB is encouraging a thaw between Havana and Washington. It has applied for an American government licence to do business in Cuba, is sending former players on a pre-Christmas goodwill tour of the island and is trying to organise an exhibition game in Havana featuring one of its teams next March. Meanwhile, Cuban baseball stars are giving Americans a new perspective on a country many perceive as nothing more than a totalitarian dystopia.

Yet the defections continue, for two reasons. The first is that the Cuban baseball authorities’ proclamations that players are now “free to go” ring hollow. It is the government, not athletes, that determines who can leave and for how long, to which country and team, and how much they will be paid. It generally selects older stars who have shown loyalty to the regime.

The second is the continuing influence of ageing “cold warriors” in the United States. Although Barack Obama has streamlined much of the bureaucracy required to authorise contracts with Cuban players, they must still establish residency outside Cuba and sign an affidavit saying that they “do not intend to, nor would [they] be welcome to, return to Cuba”. And America’s trade embargo, which can only be lifted by Congress, bans transactions with the Cuban government. That precludes any arrangement in which athletes would pay a modest tax on their foreign earnings in recognition of the state’s investment in training them, just as the United States taxes its citizens on their worldwide income. Cuba’s requirement that its players working abroad also participate in the National Series and be available to the national team represents another stumbling block, since MLB clubs would never allow their stars to skip out for an international tournament during the season, or risk injury during a long winter campaign in Cuba.

Yet for all the Cuban government’s rhetoric about America’s athletic imperialism, it may have an unlikely ally in MLB on the issues that concern it most. Despite MLB’s reputation as a fiercely capitalist industry worth $9 billion a year, the game’s economic model has much in common with Cuban-style socialist principles. To maintain fans’ interest, MLB needs a competitive balance between its rich and poor clubs. It accomplishes this by levying a tax on teams with high payrolls, and via an annual draft that routes the best young players to losing franchises. Cuban players aged over 23 with at least five years in the National Series are exempt from these rules. That enables them to auction their services to the highest bidder, undermining MLB’s carefully calibrated system of economic redistribution and reducing club owners’ profits. As a result, MLB is likely to advocate a tightly controlled system of acquiring Cuban players, rather than a free-for-all.

Moreover, MLB clubs and agents are already warning that after so many defections, the Cuban baseball pipeline is running dry and will need to be replenished. At the Premier 12, an international tournament held last month in Taiwan and Japan, Cuba finished an embarrassing sixth. The unique baseball culture Cuba has developed over 50 years of isolation has proved to be a formidable manufacturer of outstanding players. The Dominican Republic and Venezuela serve as providers of raw athletic material for MLB. Ordinary Cubans, by contrast, have grown accustomed to a remarkable closeness to world-class athletes, who play only for their home provinces and for almost no pay. “I’m just another fan,” says Reinier Reynoso, a 27-year-old pitcher for Industriales who is hanging out with the faithful outside the ballpark before a game. Fans and players “party together”, he says.

Since MLB has a keen interest in producing a new generation of Cuban superstars, it is reluctant to meddle with this potent combination of popular encouragement and state support. “We have no interest in going to Cuba and taking all of their players,” says Dan Halem, MLB’s chief legal officer. “We want Cuban baseball to thrive. We’re perfectly happy for Cuba to develop their own stars and keep them for a period of time. If they lose all their stars, fans will lose interest. There aren’t enough countries where baseball is played for this to just be a feeder for Major League Baseball.”

A recent friendly game

A recent friendly game

World champions many times over

World champions many times over

A Cuban baseball star

World champions many times over

World champions many times over