Dr. Juan Triana Cordoví, Universidad de la Habana

November 15, 2012

Submerged economy, merolicos, informal workers, cuentapropistas, self employed, a “necessary evil”, are some of the qualifiers used to describe individuals who work in the independent sector in Cuba closely reflects the fluctuations and reversals to which the non-state run economy has been exposed, and which in a way have been a thermometer for the transformations of the Cuban economy.

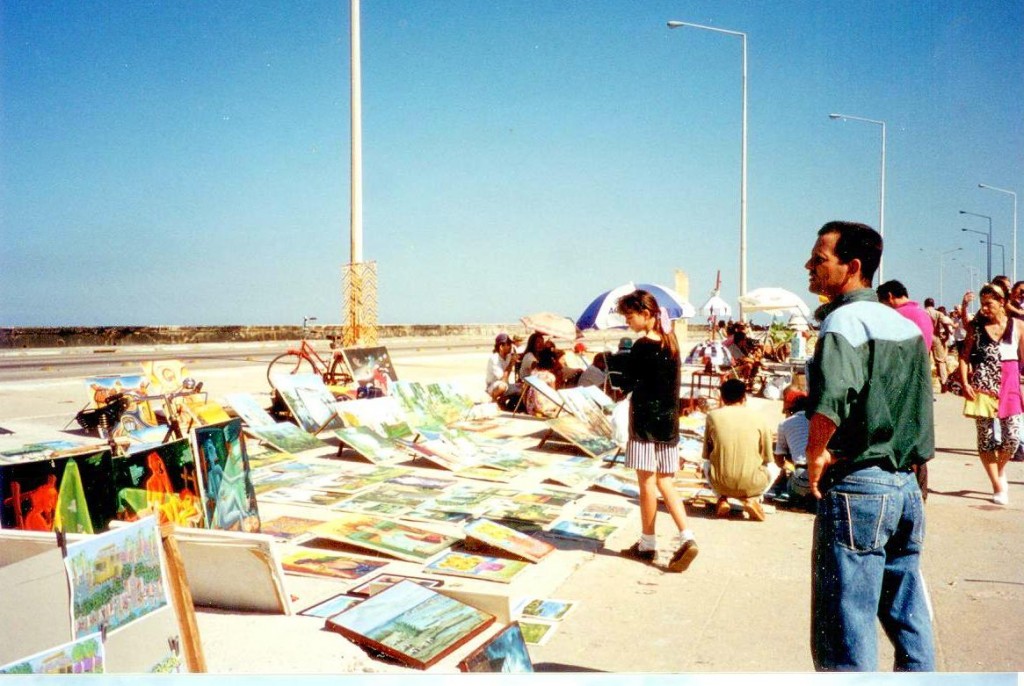

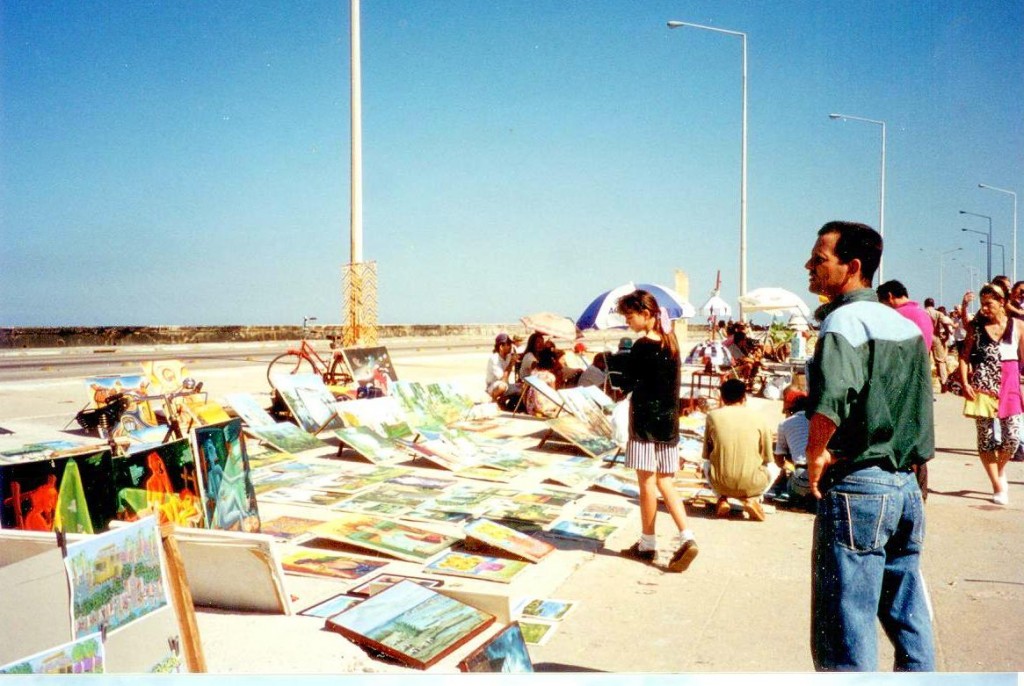

Art Market, on the Malecon. Photo by A. Ritter

Art Market, on the Malecon. Photo by A. Ritter

I. Some history: from the revolution to the rebirth of the independent work in 1993

As a result of the Cuban revolution in 1968, about 58,000 private businesses were nationalized, mostly small family businesses, focused on retail and restaurants. Some other small businesses worked in some kind of craft or industry, but these were generally low-tech. Some estimates put those businesses as employing between three and seven workers each. If we estimate an average of five workers per business, then the sector generated employment for about 300,000 people, out of a total population that exceeded six million.

Self-employment appeared when the different alternatives generated from the State failed to meet the demands of the population for different services and products (On July 3, 1978 Executive Order No. 14 was issued to regulate self-employment activities to be exercised by workers), but after a brief period of expansion, it languished in the absence of stimulus policies and its tacit rejection based on ideological and political considerations.

Self employment was revived in 19931 (Executive Decree 141) in response to the adjustments in the production and employment sectors generated by the crisis. It was accepted as a “necessary evil,” but not as an integral part of a development strategy destined to occupy a legitimate space to contribute to growth efforts 2.

Far from policies to stimulate and insert it in the operating dynamics of the economy, those policies helped to marginalize it, restrict it and prevent a qualitative transformation, which caused the decline of the sector (between 1996 and 2001 by 40%), its geographical concentration (especially in Havana) and concentration on the most profitable activities (food, transport and rentals)

That same policy that limited the access of new workers to the sector caused the generation and appropriation of undue rents, supported by the virtual monopoly in some market segments by those who “had come first,” into the sector and were later “protected” by the State. This was really ironic because the barriers to enter the sector that were created from the institutions that were supposed to “regulate” it, and the restrictive policies established, reduced competition in the “cuentapropista” sector, allowing the accumulation of income, not based on productivity and efficiency, as well as the expansion of informal channels of supply, some of them, hard to quantify, in many cases from state agencies, creating disincentives for improvement and innovation.

There were two big losers: the dynamics of the national economy, as an economic circuit was generated separately from the rest of the economy, and the population (clients) who debated between the government monopoly over some services, and the monopoly that almost unwittingly was exercised by portions of the self-employed over some (most lucrative) activities and services that were “unregulated”.

II. “Cuentapropismo” beyond “cuentapropismo”

Studies of this sector in Cuba, have often given priority to its importance for the economic liberalization and decentralization, as well as its significance from the point of view of the expansion of market relations. There is another perspective on this issue that also must be addressed. Micro, small and medium enterprises are part of the skein of any economy, regardless of the degree of development. Their contribution to employment is significant, the flexibility and maneuverability that it gives the economies (even developed economies) allowing systematic adjustments is unquestionable, and in some economies, this sector even has innovation capabilities that should not be ignored.

Until not very long ago, the “cuentapropista” sector in Cuba was a marginal sector, but this has drastically changed starting on 2011, and this trend should increase in the coming years.3

Table 1. Employment Dynamics

2008 2009 2010 2011

Total number of employed (thousands) 4.948,2 5.072,4 4.984,5 5.010,2

State sector 4.112,3 4.249,5 4.178,1 3.873,0

Cooperatives 233,8 231,6 217,0 652,1

Private 602,1 591,3 589,4 485,1

Independent workers 141,6 143,8 147,4 391,5

Source: ONEI, Anuario estadístico de Cuba 2011.

A reading of the data reveals some new features of the national economy regarding employment:

a. The total number of the employed fluctuates around five million people and it should grow significantly in the coming years.

b. The participation of the state sector continues to be decisive in total employment, but it has declined in the past two years.

c. In the non-state sector, the number of the employed decreased as a whole4, but the “cuentrapropista” sector was able to generate 244,000 jobs.

A fact that is relevant to the survival of the cuentapropista sector in the medium and long term is that it has become a significant element of employment for the country, since no other sector with so little capital is able to generate that amount of employment, so it is “socially desirable”. It is also the fastest growing sector in female employment in recent years. All these “objective reasons” give certain guarantee in the medium and long term for the existence of “cuentapropismo”. Today it is a functional sector due to the reforms undertaken in 2007 and consolidated in 2011.

A Fine New Restaurant: Paladar “Dona Eutimia”, Callejon del Chorro, Plaza de la Catedral, opened February 2010; Photo by Arch Ritter

A Fine New Restaurant: Paladar “Dona Eutimia”, Callejon del Chorro, Plaza de la Catedral, opened February 2010; Photo by Arch Ritter

III. Institutionalis m and “cuentapropismo”

Another perspective of this analysis is associated with the institutional protection that has been created to protect the independent sector.

The “modern legal network” directly associated with the expansion of self-employment was initially contained in two special issues of the Official Gazette of the Republic of Cuba published on October 25, 2011 (numbers 11 and 12, dated 1 and 8 October, respectively). They included five legislative decrees, an executive decree, an agreement of the Executive Committee of the Council of Ministers, and fourteen ministerial decisions.4 Probably due to two factors: the contraction of the foreign companies and the loans and services cooperatives.

With regards to Legislative Decree 141 of 1993, the 2011 modernization of the statute introduced obvious advantages, as it:

• Allowed commercial exchanges between “cuentapropistas” and Government entities.

• Authorized hiring a workforce, automatically converting “cuentrapropistas” into micro entrepreneurs.

• Conferred the status of taxpayers and Social Security recipients.

• Authorized access to bank financing.

• Allowed the rental of government or third party premises and assets.

• Authorized the exercise of several trades by the same person.

• Removed the restriction of having to belong to a territory to exercise a trade in it.

• Dispensed with the requirement of being retired or have some employment link to access this form of employment.

• Removed the restriction on the rental of a whole house or apartment, to allow the leasing of rooms by the hour and the use property assigned or repaired by the state in the past decade.

• Allowed the leasing of homes and vehicles to people who have residence abroad or to those living in Cuba, but leaving the country for more than three months, for which they can appoint a representative.

• Increased the capacity to fifty seats in the “paladares”, removed the restriction to employ only family members, and the ban on the sale of food products made with potatoes, seafood and beef.

As a result, a new regulatory environment has been created that exceeds the direct legal network. As part of the reform, as well as other measures authorizing the sale of houses and cars, for example, allows legal improvement to the facilities of the business, and the sale of cars which can improve the “assets” of new businesses.

In addition, the land lease policy and its recent update could facilitate the increase of supplies for those engaged in food services.

A sign that the sector considerations have changed, and that the current government wishes to convey security and transparency, is the submission to the National Assembly in the summer of 2012, of a new tax law that incorporates some additional benefits for independent workers, which include:

• The tax burden of the self employed is reduced between 3% and 7% for the segments with higher and lower income, respectively.

• A tax rate decrease for the use of labor force in the sector of self-employed workers, from 25% to 5% in the term of 5 years. It also maintains this tax exemption for the self-employed, individual farmers and other individuals authorized to hire up to 5 workers.

To these considerations we should add the “ideological and political institutionalization” of the sector, whose best expression is reflected in the words of President Raul Castro:

“The increase in the private sector of the economy, far from being an alleged privatization of social property, as some theorists claim, is destined to become a facilitating factor for the construction of socialism in Cuba, as it will allow the State to focus on raising the efficiency of the basic means of production owned by the people and release the management of nonstrategic activities for the country … we must facilitate the management and abstain from generating stigma or prejudice towards them and demonize them” ….. and later added “This time there will be no return”.

Soon, a new regulation for the operation of cooperatives in the agricultural sector will be released, which will enrich the environment in which the self-employed sector operates, will introduce new competitive challenges and make the economic fabric of the country more complex, generating new production chains.

Certainly, there is still a long way to go. Eventually it will be necessary to formally take the step from “cuentapropismo” to micro, small and medium enterprises. The time has come to consider legislation regulating a negative list (much smaller than the current listing of allowed work) of jobs that cannot be exercised privately. The time has come to incorporate offices and university professionals in jobs directly related to their careers to prevent their loss by emigration or non-use, and/or the waste of human potential unquestionably created in recent years, who have proven to be highly competitive in “other markets “. At some point, it will be necessary to incorporate into the Constitution of the Republic these new realities to begin to delineate a new economic model, but also to begin to draw a new model of development for the country, in which productivity gains and efficiency cannot be expected to only come from the state sector.

1 (*) Professor of the Centro de Estudios de la Economía Cubana, Universidad de la Habana.

(**) Cuentapropista used interchangably with self-employed in translation.

In 1993 it was established who could be self employed: state enterprise workers, retirees, the unemployed who receive subsidies from the State.10 and housewives11, and what activities, especially manual could be included, limiting access to those who could compete with the state.

2 Services that can be offered are limited and are prohibited in some geographic areas, there is no access to bank loans, workers cannot be hired as such (only allowed family work), and a high tax system is applied to independent activities … This regulation determines that the production costs must be assumed by the “cuentapropistas”.

3 In fact, the space gained by some of these “modalities” has ignored certain issues such as the “tourism extra hotels network” always considered inside the state sector but one of the weaker of the government enterprises. Today there are in Havana more than 370 private restaurants and possible more than half of them have appeared since 2011.

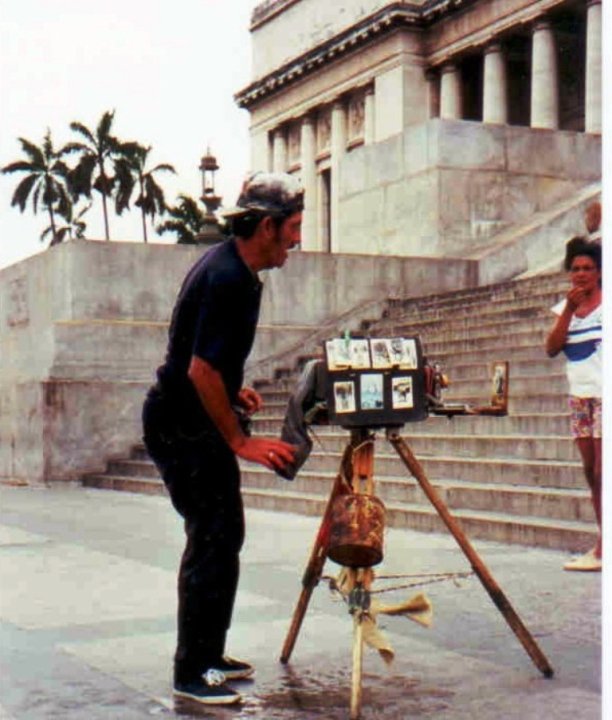

Mercado Atesanal, on the Malecon, photo by Arch Ritter

Mercado Atesanal, on the Malecon, photo by Arch Ritter

Bibliography.

Castro R. Periódico Granma, 20-12-10

Gaceta Oficial de la República de Cuba, No. 12, Edic. Extraordinaria, 8-10-12.

Vidal P. y Pérez O. Entre el ajuste fiscal y los cambios estructurales: se extiende el cuentapropismo en Cuba, Espacio Laical No. 4, 2010.

Fuentes, I. Cuentapropismo o Cuentapriapismo: Retos y Consideraciones Sobre Género, Auto-Empleo y Privatización, Cuba in Transition, ASCE, 2000

Ritter A. El régimen impositivo para la microempresa en Cuba, Revista de la CEPAL No. 70, 2000, Naciones Unidas CEPAL, Santiago Chile.

Peter P. “Cuban Entrepreneurs: From Necessary Evil to Strategic Necessity” http://www.american.com/archive/2011/january/cuban-entrepreneurs-from-necessary-evil-to-strategic-necessity

Gonzáles A. “La economía sumergida en Cuba” Revista Investigación Económica, No.2, April-June 1995, INIE.

Suárez L. M. “Cuba: nuevo marco regulatorio del trabajo por cuenta propia” en www.evershedslupicinio.com

Cuenta Propista and Artisan, Photo by Arch Ritter, November 2008

Cuenta Propista and Artisan, Photo by Arch Ritter, November 2008