They might loosen Washington’s tight grip with the help of a powerful ally: Google.

By Ricardo Martínez, Rest of World, 5 May 2021 • Mexico City, Mexico

It’s April and the sun rises over Havana at 7:07 a.m. People are already sitting outside their homes chatting about the weather reports coming from a TV that caters to multiple families. Each day, 2 million Habaneros invigorate their city’s economy by running unpaid errands, selling basic goods to people who have received dollars from relatives in Miami, or getting to work for a government-fixed wage in a state-run enterprise.

Until recently, Cuba was mostly stuck in the past. But it’s changing fast. Over the past two years, increased internet access has transformed the lives of Cubans. Cuba has become home to a thriving tech scene featuring YouTubers, influencers, artists selling NFTs, filmmakers making movies about social media, and a large group of local programmers shaping the digital conversation. They gather across dozens of mobile applications, e-commerce outfits, and digital enterprises.

Erich García Cruz is one of them. He is a 34-year-old programmer and pioneering YouTuber who wakes up around 11 a.m. every morning to his two kids and wife at a home in Havana’s Santos Suárez neighborhood. He makes breakfast — and plenty of coffee — while he begins his day by checking his phone. García Cruz is lucky because he’s one of just over 4.4 million people out of Cuba’s 11 million who have accessed the internet on their mobile devices. Mobile data did not exist for the island’s inhabitants until 2019 and SIM cards cost $40, a sum an average Cuban cannot spare. The government-controlled monthly wage is just under $88.

Cuba’s access to the internet came late compared to the rest of the world. But fast forward to 2021, and these digital pioneers are experimenting with virtual reality and toying with ideas of cyborgs. They are led by people like García Cruz and a growing tech crew of young crypto-users, AI explorers, and experimental techno DJs. They may be over 1,000 miles away from Washington, but this digital lobbying strategy is proving fruitful. It could potentially prompt companies like Google and big tech to seize the opportunity and advance their corporate interests.

While García Cruz chats over buttered toast with his family, a few blocks away, an old-fashioned radio tunes into the Communist Party-run Radio Reloj. The station provides live round-the-clock news updates. “Eleven fifteen minutes

García Cruz has been a digital entrepreneur since 2015, when the internet was barely arriving on the island. Back then, he hacked the state-controlled network through leaky internet protocols and began navigating his very own internet experience. Six years later, he knows this is only the beginning of what could be a massive economic opportunity for the island.

“There is a large segment of people in Cuba, who are seeing the internet as a platform for entertainment and one in which they can chill or simply build human connections. But I see the internet as a very powerful tool for entrepreneurship, to do business, to automate processes in real life, and to make money,” García Cruz told Rest of World. His mission is for everyone in Cuba to prosper financially from the internet instead of being glued to it as if it were a superfluous gaming console or a Facebook feed.”

Despite his optimism, García Cruz is aware of the limitations that he and millions of other internet users on the island face. They cannot fully access an array of virtual products and services provided by American companies — like Venmo or Google Earth — because of restrictions imposed by what they call “counterproductive” U.S. sanctions.

“I was born in 1986 and I never thought I would reach the point in my life where I am at now. I have achieved many things in Cuba and I’ve become an influencer,” García Cruz said. After spending years online, though, he is frustrated with the way that sanctions limit his internet experience. “It’s mind-boggling that I am personally prohibited from accessing hundreds of thousands of resources on the internet because of restrictions imposed in 1962.”

For García Cruz, the equation is simple. The only reason he can’t access a world of resources is because he is a Cuban citizen. When he tries to register for PayPal, Cuba is not among the list of accepted countries. He thinks that’s wrong — and sad. “We’re entrepreneurs, not political activists,” he said.

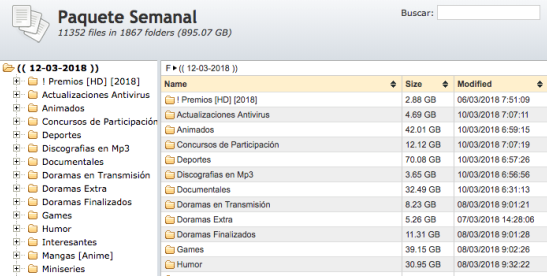

Unlike previous generations born under the embargo, García Cruz may hold a tool that can pry open the blockade from within the island: his fame. With almost 2.4 million video views and nearly 59,000 followers, his YouTube channel, Bachecubano, is arguably the most-watched tech channel in Cuba. His videos are also featured in the island’s iconic paquete, Cuba’s answer to pre-internet digital multimedia spread across the island through hard drives hand-delivered to subscribers.

Julio Lusson is another influencer in Cuba’s tech scene. He hosts a Telegram channel where thousands of Cubans — both on the island and across the Florida Straits — are planting the digital seeds for the 2020-born generation to reap.

“The internet is the strongest tool I have,” Lusson told Rest of World. “The internet right now means money, it’s investment – I benefit from it.” He lost his job as a DJ during the pandemic and credits the internet to his survival. Lusson hosts a YouTube channel featuring the latest in tech available to Cubans; TecnoLike Plus has over 1.6 million views and over 18,000 followers.

The Telegram group, which Lusson manages, is home to conversations all about the latest tech gadgets popular among young Cubans. They talk about products like the OnePlus Watch, the recent Apple Event, and about sending money to Cuba via ETECSA. There are long audio conversations about how best to make the most of gadgets locally. It’s a side effect of decades of scarcity; Cubans are the ultimate resourceful collaborators.

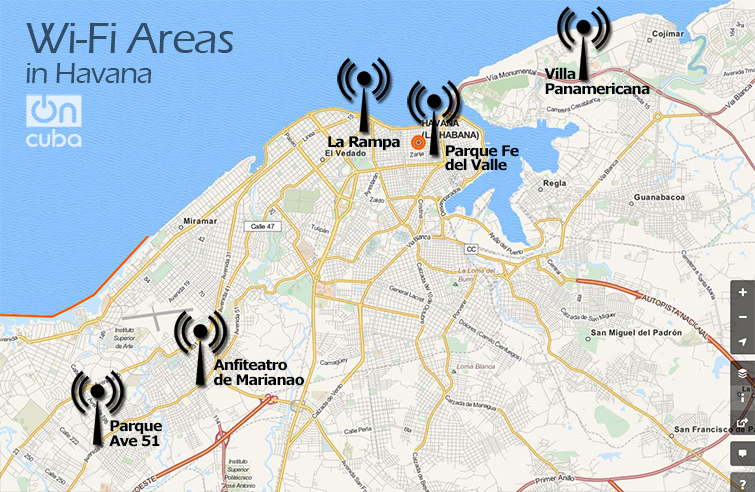

his kind of collaboration has led to speedy innovation at scale. In February 2019, Karla Suárez and Rancel Ruana founded Bajanda, a Havana-based ride-sharing app. They launched just two months after the Cuban state internet company ETECSA made data services available to mobile users — before then, Cubans could only access the internet from city hotspots and ETECSA-run internet cafes.

“The Internet is like a Pandora’s box: once you open it, there’s no turning back,” Ruana told Rest of World. “Cubans are seeing the cases of success and saying: If someone like him can develop a ride-sharing app, why wouldn’t I be able to create an app? They are seeing it’s possible to thrive from the internet.”

In less than two years, homegrown apps that are common in most other Western countries — ranging from food delivery to ride sharing — are now available to Cubans. And though Ruana is confident about his business model, he requires better services than the ones provided by ETECSA. “We have the privilege of having home internet services called Nauta Hogar,” he said, “We are lucky to live in an area where we can get that service.”

Unlike Ruana, Adriana Heredia, another Habanera entrepreneur, runs Beyond Roots, her Afro-Cuban products enterprise, solely on mobile data. It is an extremely expensive endeavour for the young Afro-Cuban economist, who promotes Cuba’s Afro-descendant culture and builds on the heritage of 3.8 million Afro-Cubans. Internet prices are a recurrent setback for many, because the price to access the internet bears no correlation when compared to the money an average Cuban can make. Everyone wants cheaper connection prices.

In March, Lusson gauged the opinion of his more than 2,000 Telegram subscribers by asking in a poll: “Do you want the blockade to end so that more of Google’s services can be accessed in #Cuba?” Of the 431 that answered, the overwhelming majority –– 88% of votes –– responded “Yes”, 2% said “No,” and 10% chose “I don’t care!” (Most likely those members residing comfortably in the U.S.).Frustration about the internet access restrictions has boiled into action. Cuba’s tech crew is more cautious about its approach to lobbying than other politically-motivated activists. García Cruz made this clear in a March 23 Telegram message when he wrote: “Politics CANNOT be allowed to go hand in hand with ONLINE BUSINESS.”

In that same post, García Cruz went on to make a digital call-to-arms, asking fellow members of the Cuban tech crew to tweet out against the blockade that left Cubans without online payment solutions. He took special care to ask people to “TAG THE CEOS of big companies, especially @BrettPerlmutter.” The Cuban Twitter community quickly jumped on board and the hashtag #EEUUnblockMe went viral.

The campaign was a success: Brett Perlmutter, head of Google Cuba, publicly championed it later on Twitter the next day and invited García Cruz to tell him more on 90 Miles, a podcast hosted by Susanna Kohly, co-founder of Google Cuba.

“This is something that’s very painful for me, personally,” Perlmutter told García Cruz on 90 Miles. “I’m sure it’s painful for every Cuban who lives in Cuba and has to face the reality of the fact that many internet services that are available to users around the world are not available to the Cuban people. And they’re not available by way of the U.S. embargo on Cuba, which actually censors information from reaching the hands of the Cuban people.”

Since 2015, Google, along with broader U.S. business coalitions, have been working together with Cuban entrepreneurs to cross this divide. Today, Cuba is connected to the internet thanks to a single submarine cable that runs from Venezuela to the island. Chinese telecoms giant Huawei has provided the government with the majority of the network’s infrastructure, including cell towers and 4G.

With increased internet access, the tech crew feels their hands would suddenly be let loose to create, innovate, and prosper. Cubans — who are hackers by nature after decades of shortages — are trusting that the internet will be their endless economic opportunity provider.

While there have been numerous efforts to normalize relations between both countries, including a September 2018 meeting in New York City between Google and Cuban President Miguel Díaz-Canel, rapprochement stalled when former president Donald Trump took office.

But Cuba’s tech crew appears to be taking an alternate route. By intensifying their contact with Google via Perlmutter, instead of looking to pressure Washington directly, their hope is that the tech giant will lobby the U.S. on their behalf. It is an effort they will have to continue pushing with the current administration; on April 16, White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki said that President Joe Biden is not considering a change in policy towards Cuba.

In spite of diplomatic uncertainty between the island and Washington, Google’s annual programming competition, Code Jam, is going forward uninterrupted. “It’s true that Google Code Jam is available in Cuba,” Perlmutter tweeted on March 27. His words were again picked up, disseminated, and praised by the Cuban tech crew, especially because the Head of Google in Cuba had endorsed yet another voice in the local tech scene, Rancel Ruana — the software engineer and founder of Bajanda.

“Hopefully other leaders in the tech world like you [Ruana] and Erich García can share this news,” concluded Perlmutter in his tweet. And he penned the hashtag #CubaIsACountry, which the Cuban Twitter community has made viral in recent weeks.

The pattern has been made clear: The tech crew and the Head of Google in Cuba play off each other in a digital effort to pressure leaders in the U.S. to reevaluate restrictions for the improvement of the island’s internet experience.

If the strategy were to succeed, it would be a win win for Google and local developers. Perlmutter could make his turf the biggest digital market in the Caribbean overnight, and the tech crew would suddenly have access to new content and lucrative opportunities. With the help of big tech companies and coalitions, Cuban developers and entrepreneurs could materialize the momentum they’ve quickly built and are pushing forward. They just don’t want political rhetoric to get in the way. The tech crew is pragmatic and can side with any company out there or even the Cuban government, so long as they are offered the internet access they desire.

Ruana, the software engineer at Bajanda, has never been to the United States, though he lives with the impacts of the sanctions every day. “I can’t access certain platforms. I would like for there to be a relaxation of restrictions to the average Cuban citizen, like me,” he said.

García Cruz finally goes to bed at 3 a.m. after hours of creative flurry in front of his computer. Just three hours later, Heredia is up brewing coffee while she reaps the digital fruits of her Afro-Cuban startup. Even with its tenuous connectivity, Havana never sleeps — the tech crew can only imagine what full internet access might mean for their island’s future.