I well remember in the 1990s in Havana. Food was in short supply; meat was almost unavailable; gasoline was out of the picture; walking. cycling and the “camello” were the chief sources of transportation. The result? My Cuban friends got thin and fit.This indeed was a general phenomenon in Cuba.

But then in the last decade or so, my friends have put on weight, some in a major way. This also seems to be a general phenomenon, and Cuba has climbed back into the ranks of the countries scoring highest in the obesity rankings, with at No. 24, with 20.1% of the male population having a body-mass index of 30 or more. (The Economist, Pocket World in Figures, 2013, p.87.)

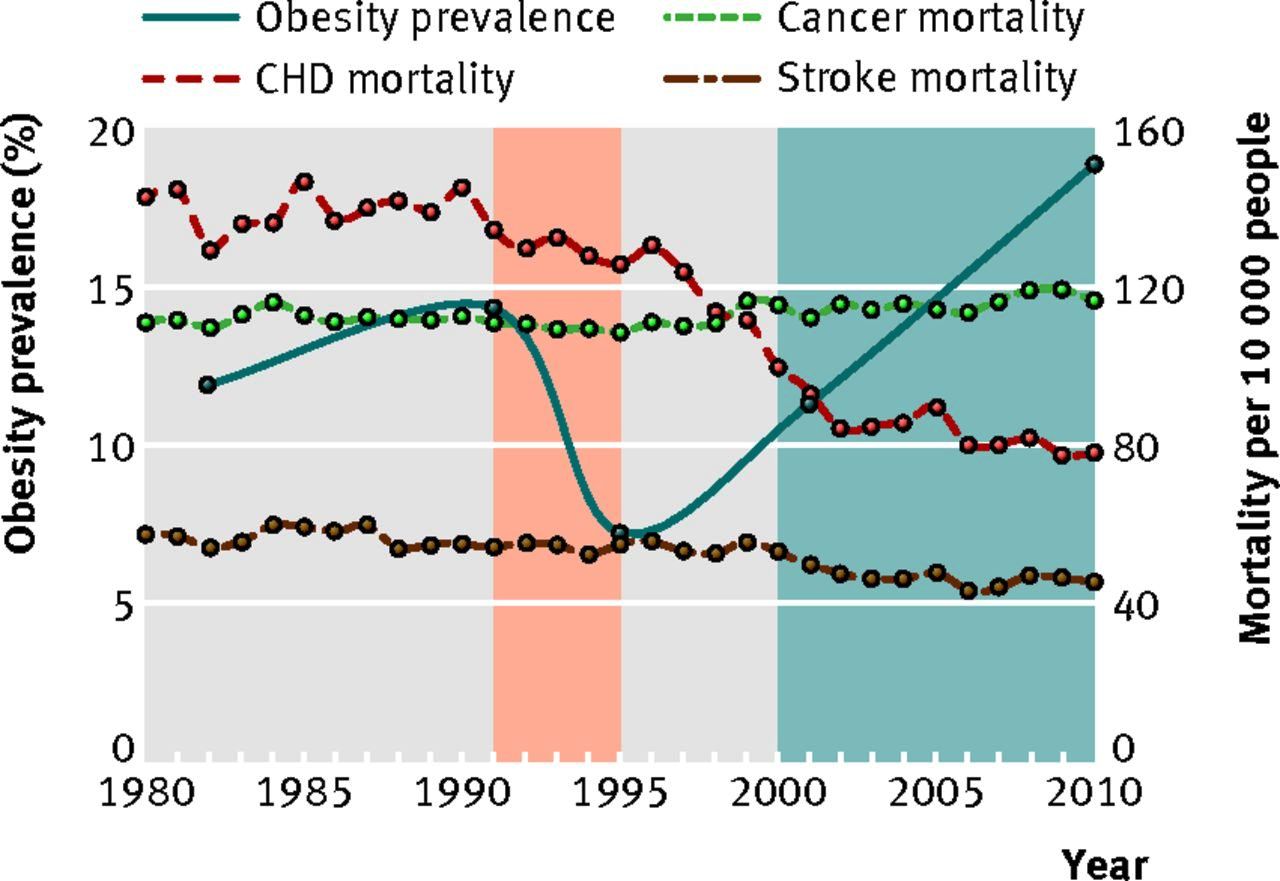

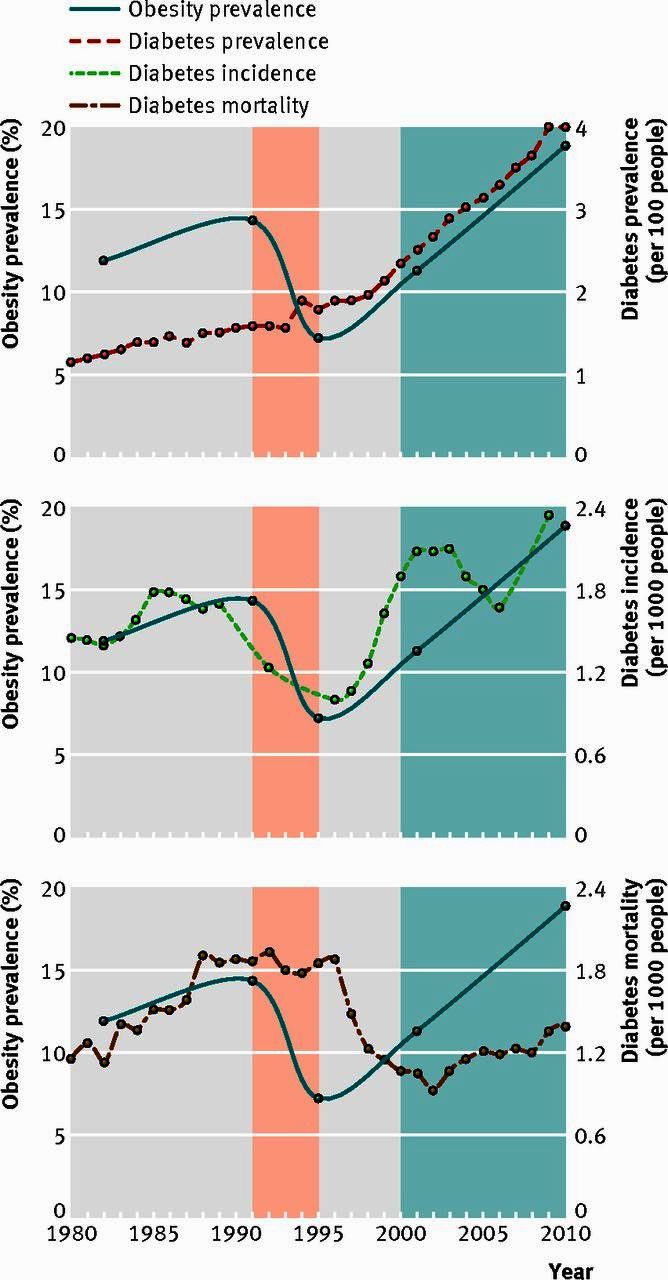

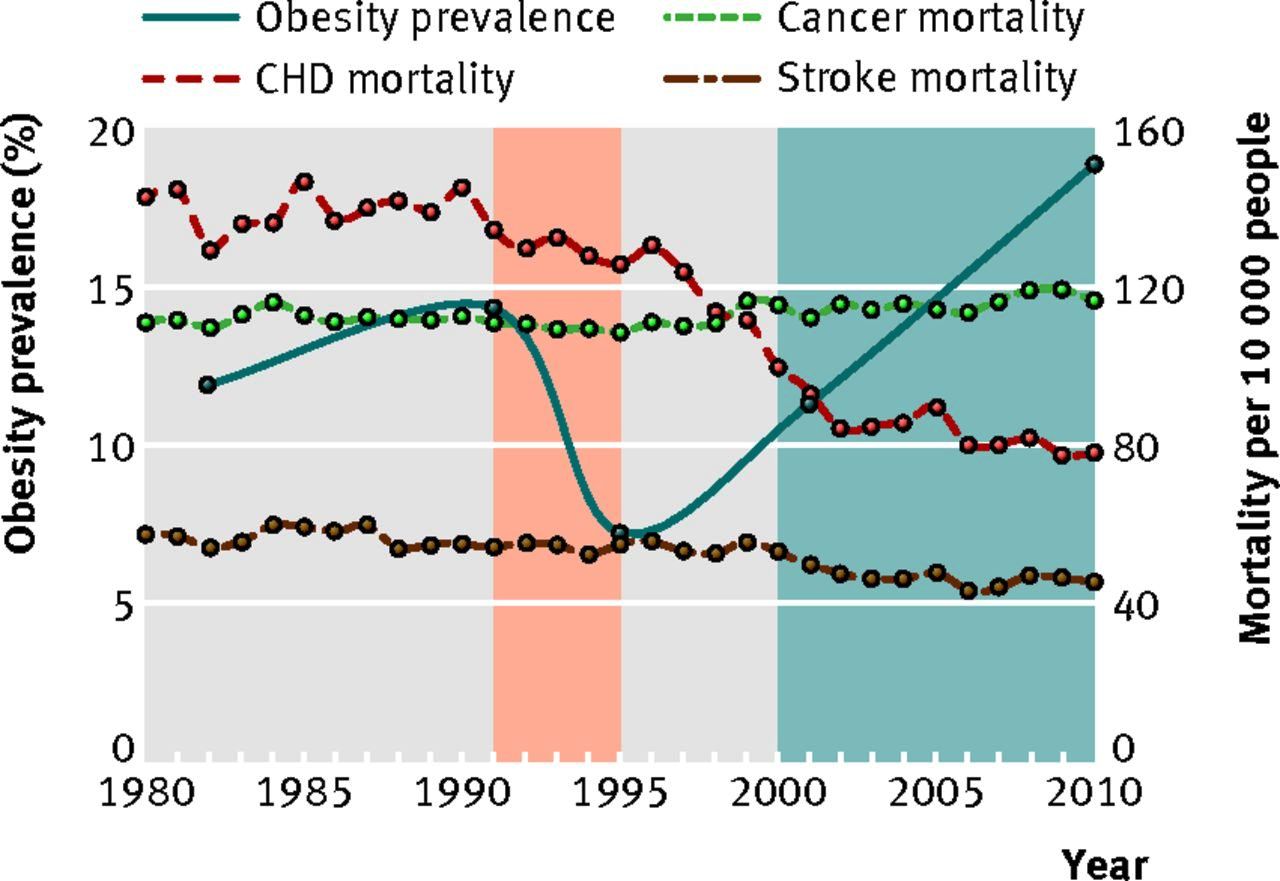

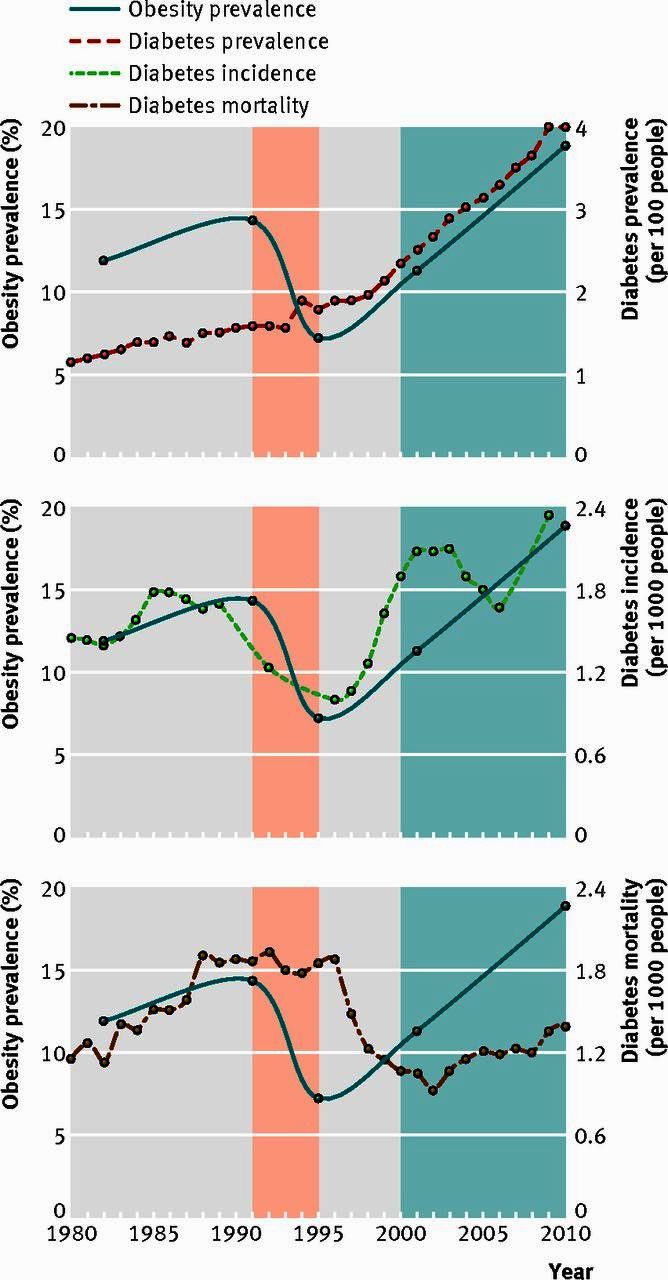

A recent study published in the BMJ Group has found that the weight losses, greater physical activity, and increased vegetable and legume consumption in this period had a variety of beneficial impacts on health, notably coronary heart disease and diabetes mortality. Then the increased food consumption (and reduced reliance on the bicycle!) during the 2000-20210 period has coincided with a worsening of some of the basic health measures.

Unfortunately the prospects for obesity and related problems may be serious for Cuba, due in part to greater food availability, and notably meat, and reduced physical activity. There also may be a psychological factor – the urge to eat a lot when food is available, having gone through earlier periods of hunger. Cuba may now be starting to face some of the same problems as the countries where obesity has become a major challenge.

The write-up of the original medical journal article in the Atlantic is presented below. The original article from the BMJ Group is located here: Population-wide weight loss and regain in relation to diabetes burden and cardiovascular mortality in Cuba 1980-2010: repeated cross sectional surveys and ecological comparison of secular trends

Authors: Manuel Franco, associate professor, adjunct associate professor, visiting researcher; Usama Bilal, research assistant, visiting researcher; Pedro Orduñez, regional adviser; Mikhail Benet, professor; Alain Morejón, assistant professor; Benjamín Caballero, professor; Joan F Kennelly, research assistant professor; Richard S Cooper, professor and chair

Richard Schiffman, The Atlantic,, Apr 18 2013

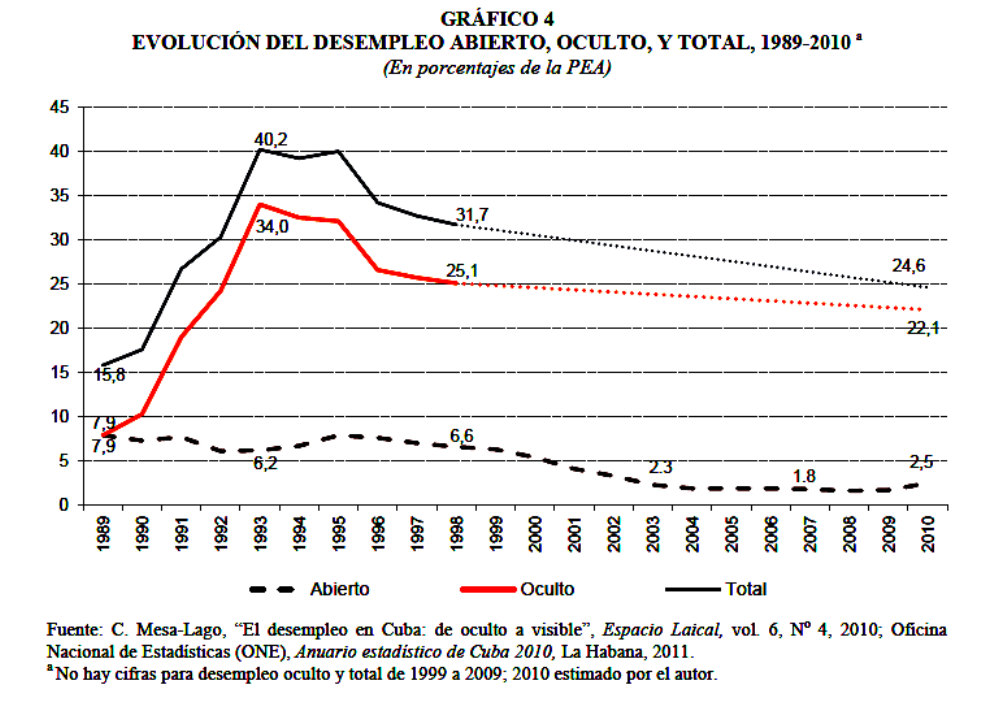

When Cuba’s benefactor, the Soviet Union, closed up shop in the early 1990s, it sent the Caribbean nation into an economic tailspin from which it would not recover for over half a decade.

The biggest impact came from the loss of cheap petroleum from Russia. Gasoline quickly became unobtainable by ordinary citizens in Cuba, and mechanized agriculture and food distribution systems all but collapsed. The island’s woes were compounded by the Helms-Burton Act of 1996, which intensified the U.S. trade embargo against Cuba, preventing pharmaceuticals, manufactured goods, and food imports from entering the country. During this so-called “special period” (from 1991 to 1995), Cuba teetered on the brink of famine. Cubans survived drinking sugared water, and eating anything they could get their hands on, including domestic pets and the animals in the Havana Zoo

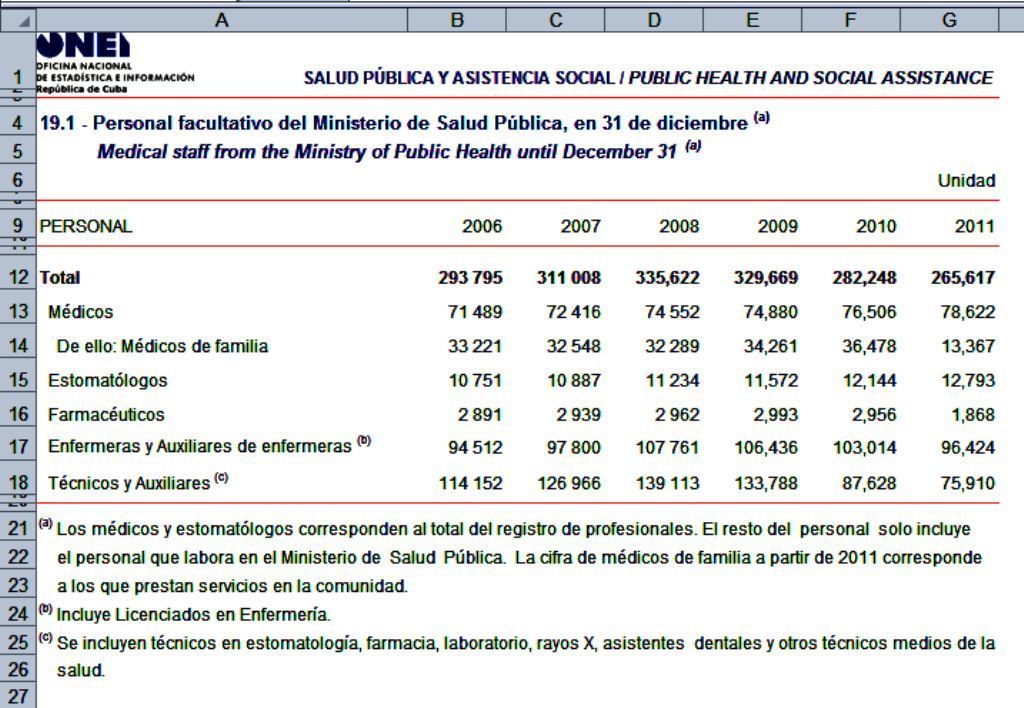

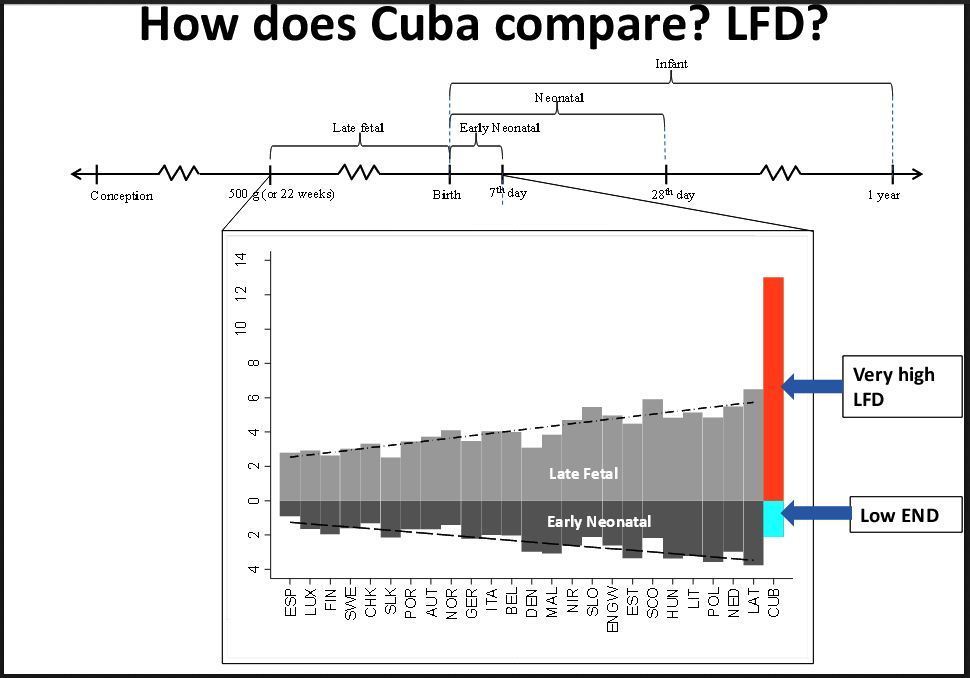

The economic meltdown should logically have been a public health disaster. But a new study conducted jointly by university researchers in Spain, Cuba, and the U.S. and published in the latest issue of BMJ says that the health of Cubans actually improved dramatically during the years of austerity. These surprising findings are based on nationwide statistics from the Cuban Ministry of Public Health, together with surveys conducted with about 6,000 participants in the city of Cienfuegos, on the southern coast of Cuba, between 1991 and 2011. The data showed that, during the period of the economic crisis, deaths from cardiovascular disease and adult-onset type 2 diabetes fell by a third and a half, respectively. Strokes declined more modestly, and overall mortality rates went down.

This “abrupt downward trend” in illness does not appear to be because of Cuba’s barefoot doctors and vaunted public health system, which is rated amongst the best in Latin America. The researchers say that it has more to do with simple weight loss. Cubans, who were walking and bicycling more after their public transportation system collapsed, and eating less (energy intake plunged from about 3,000 calories per day to anywhere between 1,400 and 2,400, and protein consumption dropped by 40 percent). They lost an average of 12 pounds.

Bicycle Parking Lot, Havana

Hydroponic Urban Agriculture, Havana

Hydroponic Urban Agriculture, Havana

It wasn’t only the amount of food that Cubans ate that changed, but also what they ate. They became virtual vegans overnight, as meat and dairy products all but vanished from the marketplace. People were forced to depend on what they could grow, catch, and pick for themselves– including lots of high-fiber fresh produce, and fruits, added to the increasingly hard-to-come-by staples of beans, corn, and rice. Moreover, with petroleum and petroleum-based agro-chemicals unavailable, Cuba “went green,” becoming the first nation to successfully experiment on a large scale with low-input sustainable agriculture techniques. Farmers returned to the machetes and oxen-drawn plows of their ancestors, and hundreds of urban community gardens (the latest rage in America’s cities) flourished.

“If we hadn’t gone organic, we’d have starved!” said Miguel Salcines Lopez in the journal Southern Spaces. Salcines is an agricultural scientist who founded “Vívero Alamar,” one of Cuba’s best known organopónicos, or urban farms, in vacant lots in Havana.

During the special period, expensive habits like smoking and most likely also alcohol consumption were reduced, albeit briefly. This enforced fitness regime lasted only until the Cuban economy began to recover in the second half of the 1990s. At that point, physical activity levels began to fall off, and calorie intake surged. Eventually people in Cuba were eating even more than they had before the crash. The researchers report that “by 2011, the Cuban population has regained enough weight to almost triple the obesity rates of 1995.”

Not surprisingly, the diseases of affluence made a comeback as well. Diabetes increased dramatically, and declines in cardiovascular disease slowed to their sluggish pre-1991 levels. (Heart disease did decline slightly in the 1980s due to improved detection and treatments.) By 2002, “mortality rates returned to the pre-crisis pattern,” according to the authors of the study. Cancer deaths, which fell in the years after the crash, also started inching up after the recovery, rising 5.4 percent from 1996 to 2010.

While the study’s author’s are cautious about attributing all of these changes in disease rates exclusively to changes in weight, Professor Walter Willett, of the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston wrote in an editorial that the study does provide “powerful evidence [that] a reduction in overweight and obesity would have major population-wide benefits.”

The findings have special relevance to the U.S., which is currently in the midst of a type 2 diabetes epidemic. Disease rates more than doubled from 1963 to 2005, and continue to rise precipitously. Diabetes and its attendant complications have been called one of “the main drivers” of rising health care costs in the U.S. by a report which was published last month by the American Diabetes Association (ADA). “Recent estimates project that as many as one in three American adults will have diabetes in 2050,” according to Robert Ratner, the chief scientific and medical officer of the ADA.

Cardiovascular disease is statistically an even bigger scourge. This illness, which was relatively rare at the turn of the twentieth century, has become the leading cause of mortality for Americans, responsible for over a third of all deaths. Heart disease is associated with our increasingly sedentary lifestyles, obesity, and artery-clogging diets.

The Cuban experience suggests that to seriously make a dent in these problems, we’ll have to change the lifestyle that helps to cause them. The study’s authors recommend “educational efforts, redesign of built environments to promote physical activity, changes in food systems, restrictions on aggressive promotion of unhealthy drinks and foods to children, and economic strategies such as taxation.”

But they also acknowledge that the changes that they are calling for are tough to engineer at the government level: “So far, no country or regional population has successfully reduced the distribution of body mass index or reduced the prevalence of obesity through public health campaigns or targeted treatment programs.”

So where does that leave us? If the United States want to stem the rise of diabetes and heart disease, either we get serious about finding ways for to become more physically active and to eat fewer empty calories — or we wait for economic collapse to do that work for us.

Fig 2 Distributions of body mass index as recorded by national surveys conducted in Cienfuegos in 1991, 1995, 2001, and 2010

Fig 2 Distributions of body mass index as recorded by national surveys conducted in Cienfuegos in 1991, 1995, 2001, and 2010

Fig 4 Obesity prevalence and coronary heart disease, cancer and stroke mortality in Cuba (1980-2010). Red shaded area=period of economic crisis; blue shaded area=period of economic recovery; CHD=coronary heart disease. CHD mortality decreased by 0.50% per year from 1980 to 1996, 6.48% per year from 1996 to 2002, and 1.42% per year from 2002 to 2010. Cancer mortality decreased by 0.12% per year from 1980 to 1996, but increased by 0.47% per year from 1996 to 2010. Stroke mortality fell by 0.39% per year from 1980 to 2000, 5.03% per year from 2000 to 2004, and 0.01% per year from 2004 to 2010

Fig 4 Obesity prevalence and coronary heart disease, cancer and stroke mortality in Cuba (1980-2010). Red shaded area=period of economic crisis; blue shaded area=period of economic recovery; CHD=coronary heart disease. CHD mortality decreased by 0.50% per year from 1980 to 1996, 6.48% per year from 1996 to 2002, and 1.42% per year from 2002 to 2010. Cancer mortality decreased by 0.12% per year from 1980 to 1996, but increased by 0.47% per year from 1996 to 2010. Stroke mortality fell by 0.39% per year from 1980 to 2000, 5.03% per year from 2000 to 2004, and 0.01% per year from 2004 to 2010

Fig 1 Physical activity, dietary energy intake, and smoking in Cuba, 1980-2010. Red shaded area=period of economic crisis; blue shaded area=period of economic recovery. Physical activity data recorded in 1987, 1988, and 1994 obtained from Havana surveys; data recorded in 1995, 2001, and 2010 come from national surveys. *1 kcal=0.00418 MJ

Fig 3 Prevalence of obesity and diabetes, incidence, and mortality in Cuba, 1980-2010. Red shaded area=period of economic crisis; blue shaded area=period of economic recovery. Diabetes prevalence increased by 2.93% per year from 1980 to 1997, and 6.27% per year from 1997 to 2010. Diabetes mortality increased by 5.85% per year from 1980 to 1989, but fell by 0.68% per year from 1989 to 1996 and 13.95% per year from 1996 to 2002, before increasing by 3.31% per year from 2002 to 2010