NOTE: For additional articles on various aspects of Fidel Castro’s presidency, see:

Fidel Castro: The Cowardice of Autocracy

Fidel’s Phenomenal Economic Fiascoes: the Top Ten

Fidel’s No-Good Very Bad Day

The “FIDEL” Models Never Worked; Soviet and Venezuelan Subsidization Did

On September 17, I published and entry on this blog entitled “Fidel’s Phenomenal Economic Fiascoes: the Top Ten” but stated that I would also write a statement on Cuba’s greatest achievements under the leadership of President Fidel Castro. Here it is.

There certainly were economic policy blunders from 1959 to mid-2006 when Fidel Castro stepped aside in favor of his brother Raul. However, as is well known, Cuba made major achievements over these years in socio-economic terms. I will begin with a quick summary of Cuba’s socio-economic performance from 1959 to 1990 and 1990-2010, and then proceed to a listing of the Tip Ten Achievements

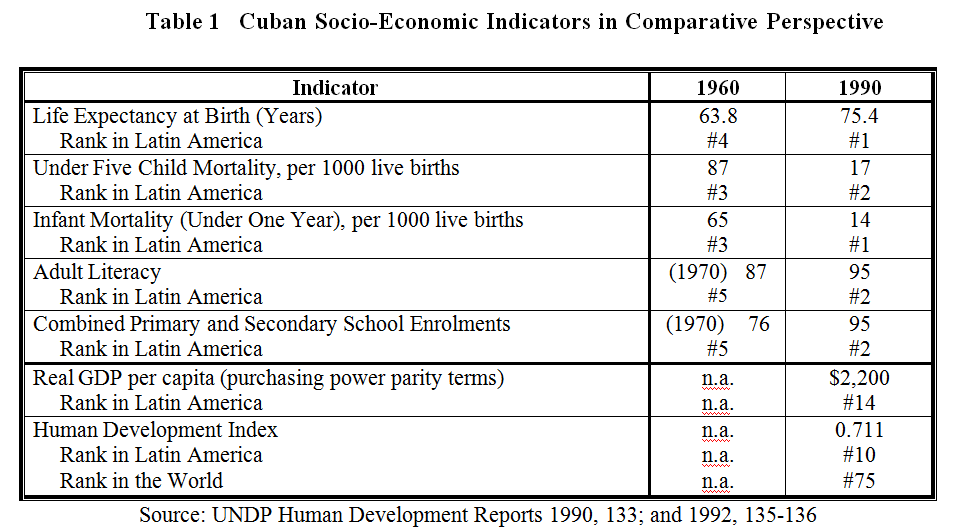

I. Socio-Economic Performance, 1959-1990

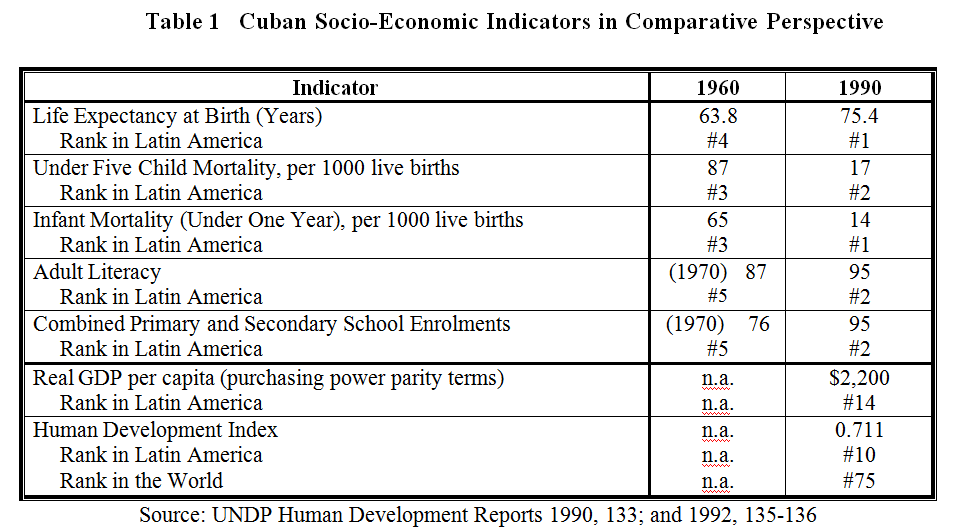

While the performance of the Cuban economy from 1959 to 1990 period was mixed, major improvements were made in terms of socio-economic well-being. The summary of changes in a few key socio-economic indicators in Table 1 illustrates the absolute and relative improvements achieved in human well-being. Life expectancy and infant and child mortality are summary indications of nutrition, income distribution and poverty and the quality of a nation’s health care system. Literacy and educational attainment are key factors in the investment in human capital and in citizen empowerment in a modern economy.

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

Cuba’s rankings for these indicators in 1960 were relatively high in the Latin American context so that it was building on reasonably strong foundations.

However, despite improvements in the rest of Latin America, Cuba raised its relative ranking for all five of the socio-economic indicators vis-à-vis the rest of Latin America (excluding the English-speaking Caribbean.) However Cuba’s economic ranking – in terms of the purchasing power of GDP per person – fell well down the list in 1990 placing Cuba at the 14th rank. As a result, Cuba placed at #10 in the UNDP Human Development Index.

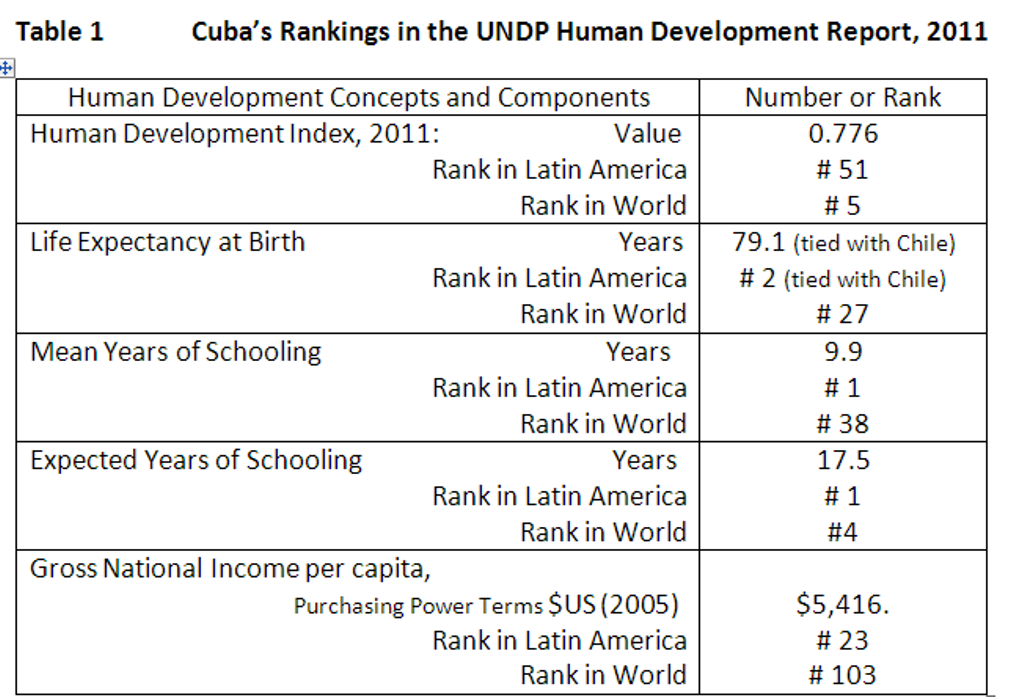

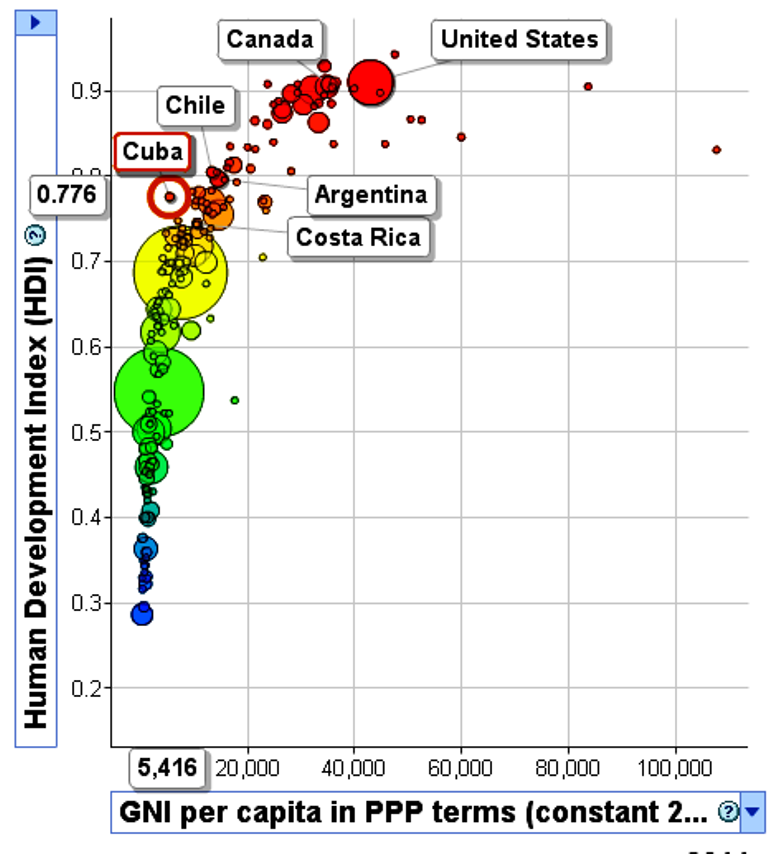

II. Socio-Economic Performance 1990-2010

Despite the economic difficulties of the 1990s, Cuba continued to improve its socio-economic performance in relative and absolute terms, at least as these are measured by the indicators in Table 2. Cuba continued to lead the Latin American countries in infant mortality and the education indicators. The improvements in education and health indicators and rankings occurred despite weakening of resource allocations and problems of maintaining quality. Cuba’s success in these areas was due largely to the quality and quantity of the educational systems built up in the previous1960-1990 period and institutional momentum.

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

III. Top Ten Achievements

Here is a listing of the Cuba’s socio-economic and economic achievements under the Presidency of Fidel Castro. They are not presented in order of importance. Some are the result of specific policy decisions or design or negotiations of Fidel Castro, though others are not.

#1 The 1961 Literacy Campaign

#2 Reorganization of the Health Sector

#3 Redesign of the Educational System

#4 Rapid Expansion of the Tourism Sector

#5 Provision of Medical Services to Latin America and Other Countries

#6 Survival in the Face of the 1989-1993 Economic Melt-Down

#7 Winning Economic Support from the Soviet Union, 1961-1990 and Venezuela, 2004-2010

#8 Establishment of the “Polo Cientifico” and the Development of the Bio-Technological Sector

#9 Dedication to their Jobs by Cuban Citizens during the Catastrophic Decline in Real Wages and Incomes after 1990

#10 Fruitful Collaboration with Foreign Enterprises

IV. Achievements in Detail

#1 The 1961 Literacy Campaign

The 1961 literacy campaign was an inspired approach to improving educational levels among the relatively large proportion of the population that was illiterate in 1959. This was done at relatively low cost with strongly motivated volunteers. It quickly improved literacy rates immensely, though there is some disagreement as to the quality of the literacy that was achieved.

#2 Reorganization of the Health Sector

#2 Reorganization of the Health Sector

Cuba succeeded in reorganizing its medical system so as to provide universal access to health services, and managed to obtain excellent results relative to the amounts of resources that it was able to devote to the health sector. As a result, Cuba’s health indicators improved quickly and remain among the very best in Latin America (See Tables 1 and 2)

#3 Redesign of the Educational System

Cuba’s reorganization and expansion of the educational system in the early 1960s also made education universally accessible and increased investment in people (human capital.) As a result, Cuba moved from 5th place in Latin America in terms of literacy and school enrolment in 1970 to 1st in 2007 – a fine achievement.

#4 Rapid Expansion of the Tourism Sector

As a result of the 1989-1994 economic melt-down, it was decided to earn foreign exchange by expanding the tourist sector. This required massive involved massive investment by both Cuba and foreign enterprises and the rapid shifting of resources to the sector. This was done and by 2008, Cuba was earning almost MN 2.4 billion from tourism.

#5 Provision of Medical Services to Latin America and Other Countries

By the latter 1990s, Cuba had a major surplus of medical personnel, with doctors and nurses posted in small tourist hotels and day care centers. However, this was converted into a major humanitarian asset, with Cuba’s provision of medical assistance to many countries in need, and expanding the Latin American Medical School outside Havana. The services of medical personnel are also exported to other countries – paid mainly by the Government of Venezuela. The foreign exchange earnings from medical (and educational) service exports amounted to MN 6.1 billion, almost half of Cuba’s foreign exchange earnings in 2008, as indicated in the accompanying chart.

#6 Survival in the Face of the 1989-1993 Economic Melt-Down

With the loss of Soviet subsidization and the near 40% decline in income per capita from 1989 to 1994, Cuba reorganized its economy, “depenalizing” the use of the US dollar, legalizing farmers’ markets, liberalizing self-employment and promoting new economic activities and exports etc. With no support from the international financial institutions of which it was not a member, thanks to the embargo with the United States, Cuba survived, at a cost borne almost directly, immediately and totally by its citizens.

#7 Winning Economic Support from the Soviet Union, 1961-1990 and Venezuela, 2004-2010

As noted in an earlier blog, The “FIDEL” Models Never Worked; Soviet and Venezuelan Subsidization Did posted on September 9, 2010 , Cuba received generous subsidization from the Soviet Union for a substantial period of time. An estimate of the amount of the subsidization is presented in the accompanying chart. Presumably President Fidel Castro is responsible for negotiating this support. Similarly, Cuba has received substantial support from President Chavez of Venezuela through export and investment credits, low-cost oil imports and generous payments for Cuba’s exports of medical services. How beneficial any of this assistance has been is debatable partly because it has been and is unsustainable and it has made possible the continuation of economic policies and institutions that have been counterproductive in the longer term. Fidel Castro can undoubtedly take the credit for these special relationships.

(click to enlarge)

(click to enlarge)

#8 Establishment of the “Polo Cientifico” and the Development of the Bio-Technological Sector

To my knowledge, there has been no careful analysis of Cuba’s huge investment in the “Polo Cientifico” and the Bio-Technological sector. Indeed, I have not seen any analysis of the investment in the sector so I cannot judge accurately if it has been commercially viable so far or not.

However, Cuba is beginning to achieve major exports of pharmaceutical products amounting to MN 296.8 million pesos vis-à-vis MN 233.4 million for sugar in 2008. These exports should continue to increase in future and the investment in the sector may be valuable. Moreover, Cuba’s investment in the “Polo Cientifico” has built a professional and institutional foundation for future success in pharmaceutical and other scientific areas.

However, Cuba is beginning to achieve major exports of pharmaceutical products amounting to MN 296.8 million pesos vis-à-vis MN 233.4 million for sugar in 2008. These exports should continue to increase in future and the investment in the sector may be valuable. Moreover, Cuba’s investment in the “Polo Cientifico” has built a professional and institutional foundation for future success in pharmaceutical and other scientific areas.

#9 Dedication to their Jobs by Cuban Citizens despite the Decline in Real Incomes after 1990

I have always been impressed at the professionalism of many Cuban citizens that I have known over the years since 1990. In the face of huge declines in the purchasing power of their incomes, they continued to work seriously and with dedication in medicine, the Universities, the schools, the public service, or other employment. Many professionals and others in effect subsidized their state sector employers by earning other incomes that permitted them to survive in the unofficial economy. We have all heard of the doctors and engineers forced to provide taxi services on the side in order to make ends meet and continue to function in their professional capacities. The dedicated work of countless citizens over the difficult years of the Special Period, 1990-2010, is essentially what has brought about some recovery since the depths of the depression in 1993.

#10 Fruitful Collaboration in Nickel, Oil, Gas and Electric Power Generation with Sherritt International

Cuba opened up to foreign direct investment in joint venture arrangements with state firms. This has paid off handsomely, most notably with Sherritt International (nickel, cobalt, oil, gas, and electric power) and other enterprises as will be argued later in this Blog.