By Arch Ritter

[Note: a subsequent Blog Entry will analyze “Consequences and Courses of Action” ]

Since 1989, Cuba has experienced a disastrous de-industrialization from which it has not recovered. The causes of the collapse are complex and multi-dimensional. Is it likely that the policy proposals of the Lineamientos approved at the VI Congress of the Communist Party of Cuba will lead to a recovery from this collapse? What can be done to reverse this situation?

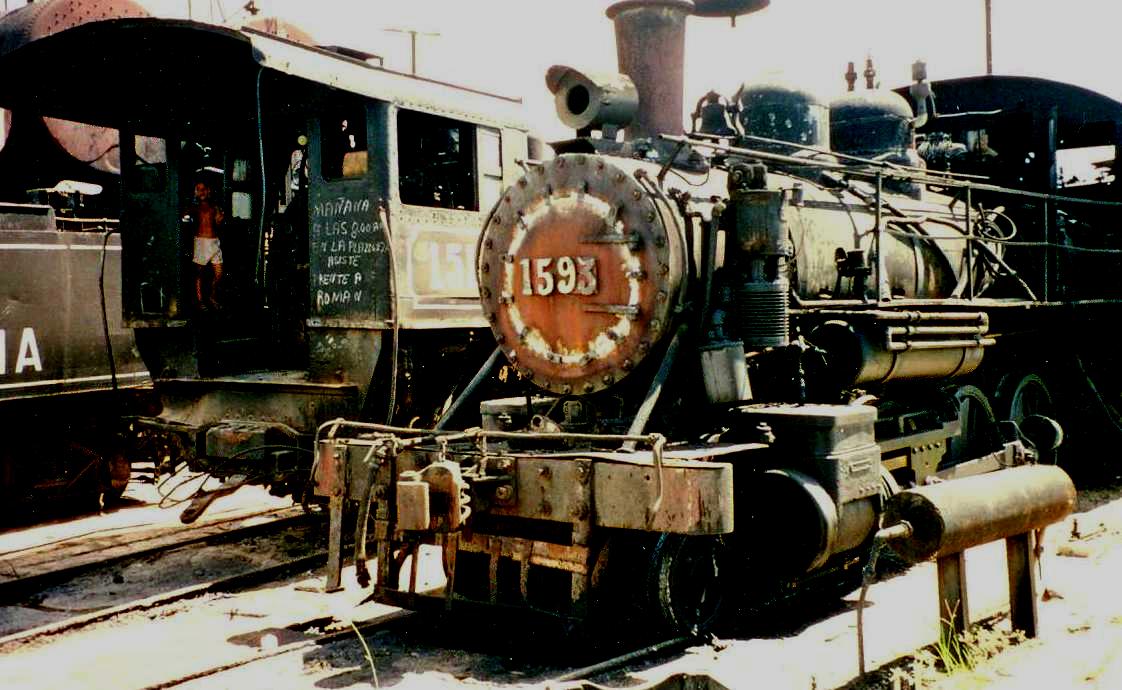

One of the last Cane-Harvesting Machines Fabricated in Cuba, en route to its Destination, November 1994

One of the last Cane-Harvesting Machines Fabricated in Cuba, en route to its Destination, November 1994

Perhaps it should be noted to begin with that the manufacturing sector of many if not most high income countries have shrunk as a proportion of GDP and especially in terms employment. This has been due to the migration of labor-intense manufacturing to lower wage countries, most notably China and India, as well as technological change and rising labor productivity in many areas of manufacturing. However, given Cuba’s income levels and its historical record, it could and should be expanding its manufacturing base and perhaps even increasing employment in the sector rather than remaining in melt-down phase

I. Characteristics of Cuba’s De-Industrialization, 1989-2010

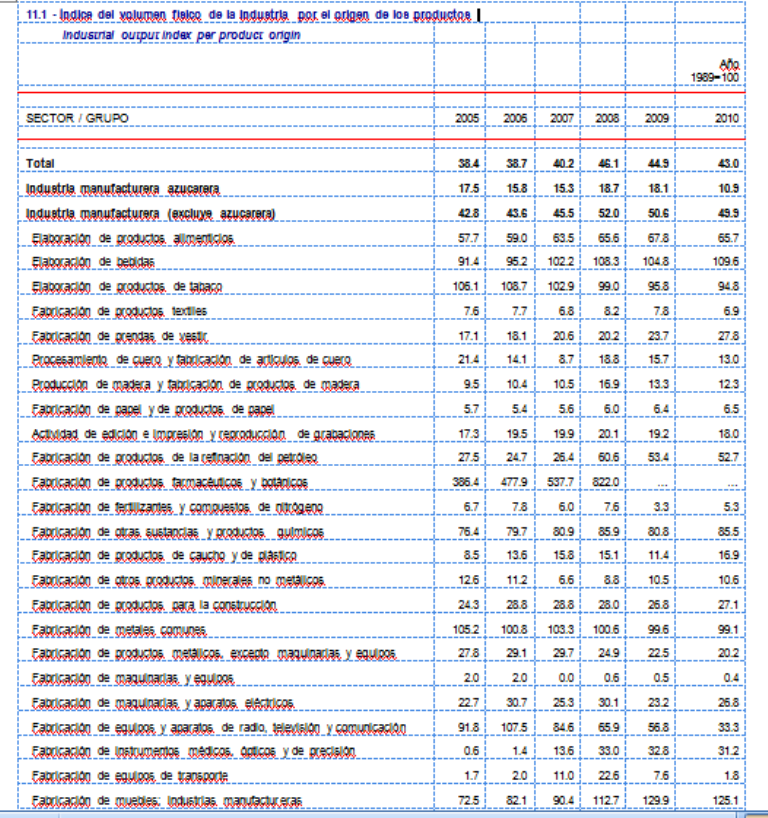

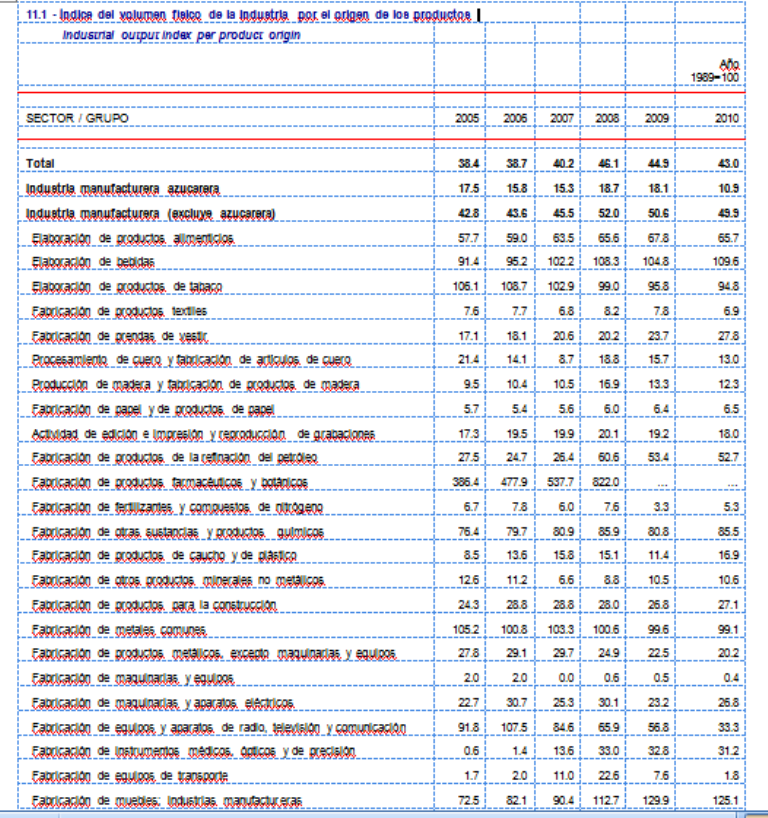

The accompanying Charts and Tables, all using data from Cuba’s Oficina Nacional de Estadisticas, indicate the severity of Cuba’s manufacturing situation.

Chart 1 illustrates the almost 60% decline in the physical volume of industrial output – excluding sugar – from 1989 to 1998. By the year 2010, the level of output was at 49.9% of the 1989 level. This does not constitute a recovery.

The physical volume of output by destination is presented in Appendix Table 11.2 below. This Table indicates industrial output including sugar in 2010 was at 43% of its 1989 volume. Products for Consumption were at 81.8% of their 1989 value in 2010. Some product areas had improved, namely manufactures for consumption and “other manufactures” but food drink and tobacco production were at 71.5% of their 1989 volume. Footwear and clothing were at 21.8% of their 1989 volume. Equipment production had almost totally disappeared and was at 6.6% of their 1989 volume in 2010. Intermediate products were at 34.7% of their 1989 volume, despite a near 50% increase in volumes of mineral extraction. .

The physical volume of output by destination is presented in Appendix Table 11.2 below. This Table indicates industrial output including sugar in 2010 was at 43% of its 1989 volume. Products for Consumption were at 81.8% of their 1989 value in 2010. Some product areas had improved, namely manufactures for consumption and “other manufactures” but food drink and tobacco production were at 71.5% of their 1989 volume. Footwear and clothing were at 21.8% of their 1989 volume. Equipment production had almost totally disappeared and was at 6.6% of their 1989 volume in 2010. Intermediate products were at 34.7% of their 1989 volume, despite a near 50% increase in volumes of mineral extraction. .

Volumes of industrial output by origin or industrial sub-sector are presented in Appendix in Table 11.1 Some manufacturing sub-sectors have virtually disappeared with production at very low levels as a percentage of 1989 levels. For example, for the following sectors, 2010 levels as a percentage of 1989 levels were as follows:

- Textiles: 6.9%

- Clothing: 27.8%

- Paper and paper products: 6.5%

- Publications and recordings: 18.0%

- Wood products: 12.3%

- Construction Materials: 27.1%

- Machinery and Equipment: 0.4%

On the other hand, pharmaceutical production increased dramatically, with 2008 production at 822% of the 1989 level. Tobacco, drinks (presumably alcoholic) and metal products were approximately at the 1989 levels. But almost everything else was around 25% of the levels of 1989 or less.

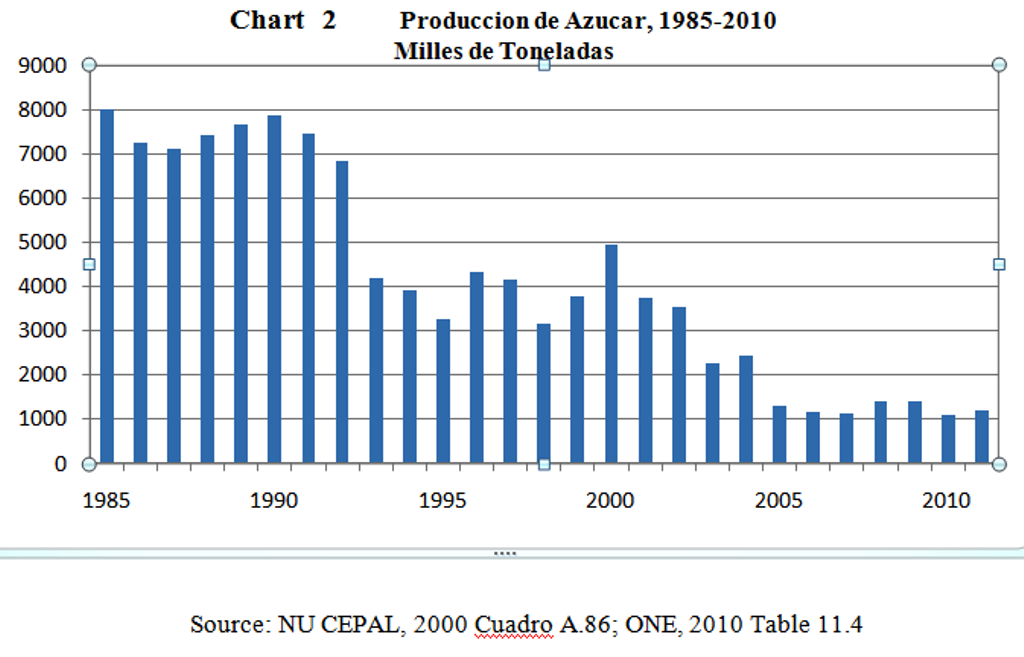

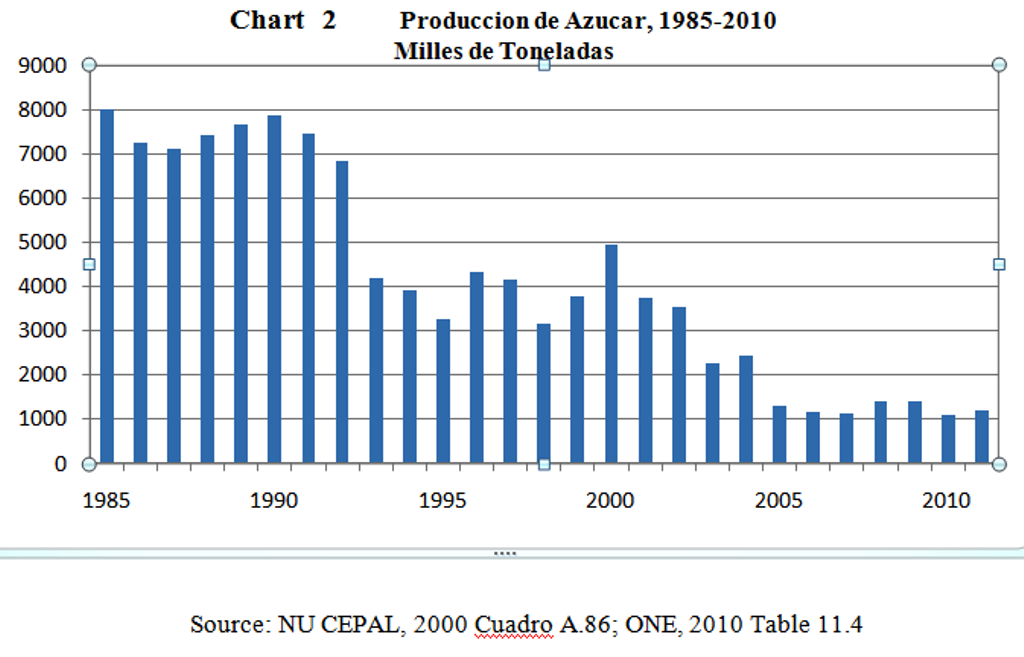

The collapse of the sugar agro-industrial complex is well known and is illustrated in Chart 2.

II. Causal factors

II. Causal factors

There are a variety of reasons for the collapse of the industrial sector.

1. The initial factor was the ending of the special relationship with the Soviet Union that subsidized the Cuban economy generously for the previous 25 years or so. This resulted from the shifting of the Soviet Union to world prices in its trade relations with Cuba rather than the high prices for Cuba’s sugar exports as well as an end to the provision of credits to cover Cuba’s continuing trade deficits with the USSR. The break-up of the Soviet Union and recession in Eastern Europe also damaged Cuba’s exports. These factors reduced Cuba’s imports of all sorts, especially of imported inputs, replacement parts, and new machinery and equipment of all sorts. The resulting economic melt-down of 1989-1993 reduced investment to disastrous levels and resulted in cannibalization of some plant and equipment for replacement parts. The end result was a severe incapacitation of the manufacturing sector.

2. The technological inheritance from the Soviet era as of 1989 was also antiquated and uncompetitive, as Became painfully apparent after the opening up of the Soviet economy following Perestroika.

3. Since 1989, levels of investment have been continuously insufficient. For example, the overall level of investment in Cuba in 2008 was 10.5% of GDP in comparison with 20.6% for all of Latin America, according to UN ECLA, (2011, Table A-4.)

4. Maintenance and re-investment was also de-emphasized even before 1989. After 1989, maintenance and re-investment were a category of economic activity that could be postponed during the economic melt-down – for a little while. But over a longer period of time, lack of adequate maintenance of the capital stock has resulted in its serious deterioration or near destruction. This can be seen graphically by the casual observer with the dilapidated state of housing in Havana and indeed the frequent “derrumbes” or collapse of houses and abandoned urban areas.

5. The dual monetary and exchange rate system penalizes traditional and potential new exporters that receive one old (Moneda Nacional) peso for each US dollar earned from exports – while the relevant rate for Cuban citizens is 26 old pesos to US$1.00. This makes it difficult if not impossible for some exporters and was a key contributor to the collapse of the sugar sector.

6. The blockage of small enterprise for the last 50 years has also prevented entrepreneurial trial and error and the emergence of new manufacturing activities.

7. Finally, China has played a major role in Cuba’s de-industrialization as it has done with other countries as well. China has major advantages in its manufacturing sector that have permitted its meteoric ascent as a manufacturing power house. These include

- Low cost labor;

- An industrious labor force;

- Past and current emphases on human development and higher education;

- A relatively new industrial capital stock;

- Massive economies of scale;

- Massive “agglomeration economies”;

But of particular significance has been its grossly undervalued exchange rate that has permitted it to incur continuing trade and current account surpluses and amass foreign assets now amounting to around US$ 3 trillion. Indeed, in my view, China has cheated in the globalization process and captured the lion’s share of its benefits through manipulation of the exchange rate, and has contributed to the generation of major imbalances for the rest of the world, including both the United States and Cuba among other countries. .

China’s undervalued exchange rate has co-existed with Cuba’s grossly overvalued exchange rate that has been partly responsible for pricing potential Cuban exports of manufactures out of the international market. The result is that Cuba is awash with cheap Chinese products that have replaced consumer products that Cuba formerly – in the 1950s as well as the 1970s – produced for itself.

With respect to the sugar sector, there are a number of factors have been responsible for its decline.

1. Most serious, the sector essentially was a “cash cow” milked to death for its foreign exchange earnings, by insufficient maintenance and by insufficient re-investment preventing productivity improvement.

2. The monetary and exchange rate regimes under which it labored have also damaged it badly. Earning one “old peso” for each dollar of sugar exports has deprived the sugar sector of the revenues needed to sust4ain its operations.

3. Finally the decision by former President Fidel Castro to shut down close to half the industrial capacity of the sector and try to convert former sugar lands to other uses sealed its fate. In view of Cuba’s natural advantages in sugar cultivation, the sophistication and diversity of the whole sugar agro-industrial cluster of activities, the high sugar prices of recent years and the competitiveness of ethanol derived from sugar cane, this decision was foolish in the extreme.

Next: Part II, The Consequences of Deindustrialization and Possible Future Courses of Action. will be published in the next Blog Entry