BBC, 22 May 2013 Last updated at 00:15 ET

The chimneys are back at work in the Cuban sugar town of Mejico It is a sight the people of Mejico thought they would never see again – sugar cane pouring onto a conveyer belt, beneath chimneys pouring smoke into a bright blue sky. Silent for seven years, the town’s sugar mill has been given a new lease of life.

Sugar was Cuba’s biggest export until the 1990s, providing half a million jobs. But when the Soviet market disappeared and the world sugar price sank, almost two-thirds of the island’s mills had to close. At those that remained, production plummeted. Weeds overran the cane fields, and abandoned sugar plants – once the heart of many communities – fell into ruin.

‘Tough blow’

But Mejico is one of more than a dozen mills gradually being salvaged as Cuba looks to capitalise on a recent rise in sugar prices and improved yields in its cane-fields.

The mill in Mejico dates back to 1832, when the canefields were worked by slaves housed in nearby barracks “When they said the mill would stop working, it was a tough blow,” says Ariel Diaz, who used to work as an engineer at the old mill before it shut down in 2006. “It really traumatised us,” he says of its closure, which happened almost overnight.

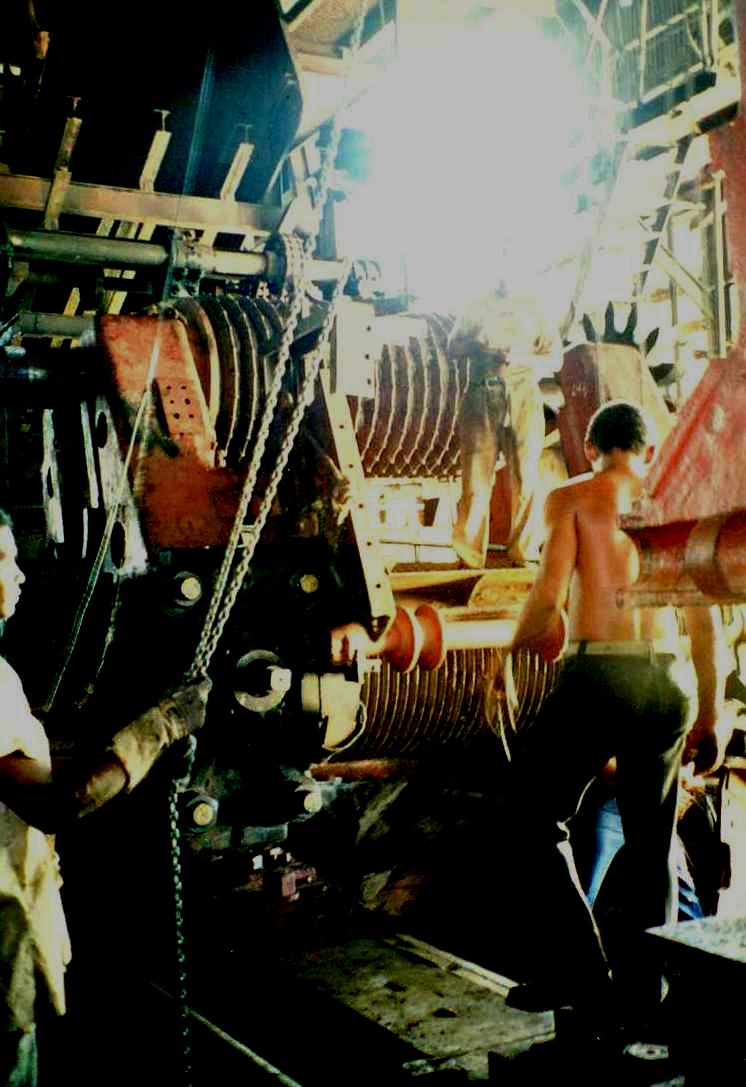

There had been a mill in Mejico since 1832. The original stone slave barracks are still standing – converted into workers’ housing. “We were nothing without the mill. It was our life,” Mr Diaz says, now happy to be back in the noisy, steamy sheds shouting orders to his team as huge metal cogs turn down below..

Repairs, Australia Sugar Mill, 1994, (now converted to a museum). Photo by Arch Ritter

Centuries-old tradition

The re-opening has created some 400 new jobs in the mill itself. Sixteen farmers’ co-operatives are supplying it with cane. The country needs to produce sugar, and we can help”

Across Cuba, as mills closed, many people were redeployed to collective farms; others were paid to study and re-qualify. “Clearly people were affected, especially psychologically,” a spokesman for state sugar company Azcuba, Liobel Perez, accepts. “The mills represent years, centuries, of tradition so it was very hard. But steps were taken to help.”

Just a short drive from Mejico, the chimneys of the Sergio Gonzalez mill are still cold some 15 years after the last sugar rolled off the conveyer belts. Weeds poke out of holes in the concrete. The old sheds have been partially dismantled and are rusting.A sorry-looking stage has a faded pro-revolution slogan painted across it: “Revolucion, Si!”

“All the families here lived off the mill, and life was much easier,” recalls Argelio Espinosa, a mill mechanic for many years. He now sells slush-ice drinks from a street cart, one of the small, private businesses that communist Cuba now allows. But sales in such a poor town are slow and Mr Espinosa echoes many who say the mill closure brought other difficulties.

“When the mill was open there was always transport for the workers and everyone used it. Now there’s just two buses a day,” he points out. “It’s the same with the water. When the mill was grinding, it needed water and we were never short. Now we have problems,” he adds.

The locals talk of how new businesses, like a spaghetti factory, were brought to other former sugar towns. In Sergio Gonzalez, the luckiest now hitch a ride 80km north for jobs in the tourist resort of Varadero.

Challenges ahead

By contrast, there is a fresh buzz of activity in Mejico. In the nearby fields, workers have been rushing to cut the cane before the weather turns. A shiny new Brazilian harvester charges forward, swallowing up the cane as it goes. Cuba has invested in some new equipment to kick-start its revamped sugar business. It is one of four machines Cuba invested in for the mill re-opening, far more efficient than the aging, Soviet alternative.

There have been teething troubles with the re-opening. New machine parts arrived late, the workforce is young and inexperienced, and production is below target. Senior staff have slept little, under pressure to perform.

But the whole community is willing this to succeed. Some pensioners are helping out at the mill for free, passing their expertise to a new, young generation. And many sugar workers who took up farming when the mill closed have hung up their spades and returned.

“They like the mill. It’s a tradition here, more than anything. And it’s more secure work, right next to their homes,” explains mill director Jesus Perez Collazo. “There are a lot of challenges. The harvest is not as good as we wanted but the country needs to produce sugar, and we can help,” he says.

China buys 400,000 tonnes of sugar from Cuba a year; now production is increasing, Azcuba says international brokers are also knocking at the door.

New life

With the revamped mills back online, the eventual target is three million tonnes per year, though persistent inefficiencies mean this year’s harvest will fall well below that.

Some old-time sugar workers are passing on their knowledge to a new generation of workers. “Sugar is once more becoming one of our principal export goods and that will be reinforced in the years to come,” argues spokesman Liobel Perez.. Despite the difficulties, those are welcome words in Mejico.

As the day cools, men gather in the main square watching the mill smoke rise and discussing the harvest. For some, like 68-year old Joel, the re-opening has meant coming out of retirement. “I need the money,” he says bluntly. At $35 a month, his mill salary is more than three times his pension. Others take a broader view. “There was no life, no movement here without the mill,” one man comments. “This place was like a cemetery.”

Now Mejico is shuddering back to life.

Australia Sugar Mill, 1994

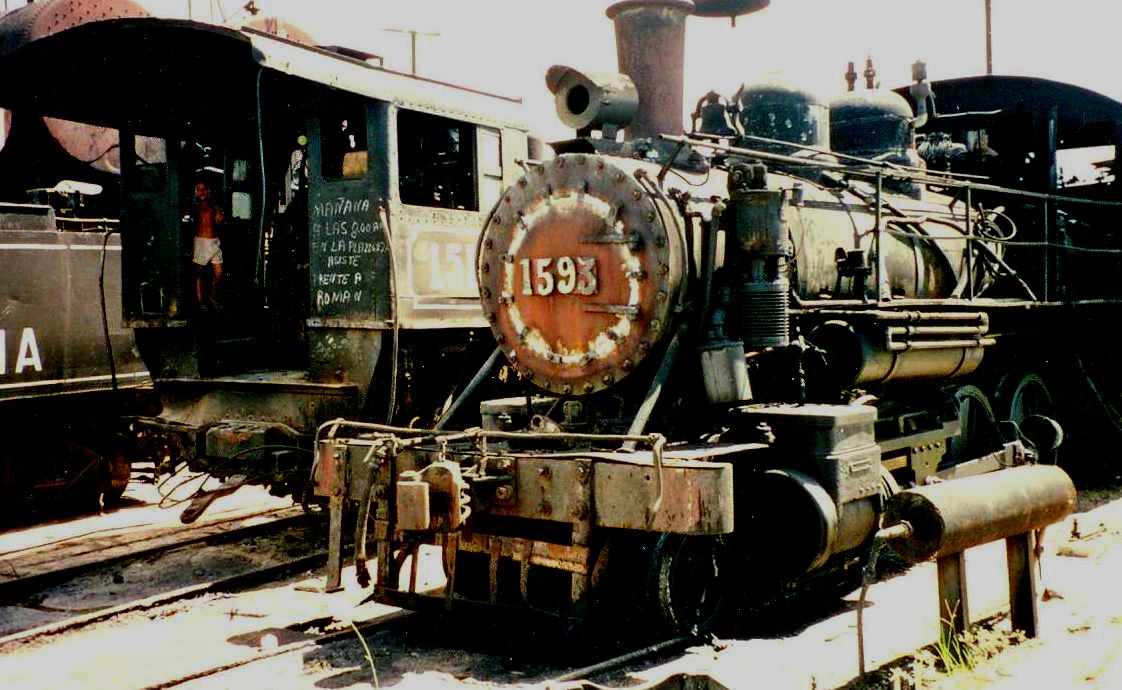

Steam Locomotives, vintage +/- 1910, at the Australia Sugar Mill, 1994, Photo by Arch Ritter