By Arch Ritter, October 5, 2013

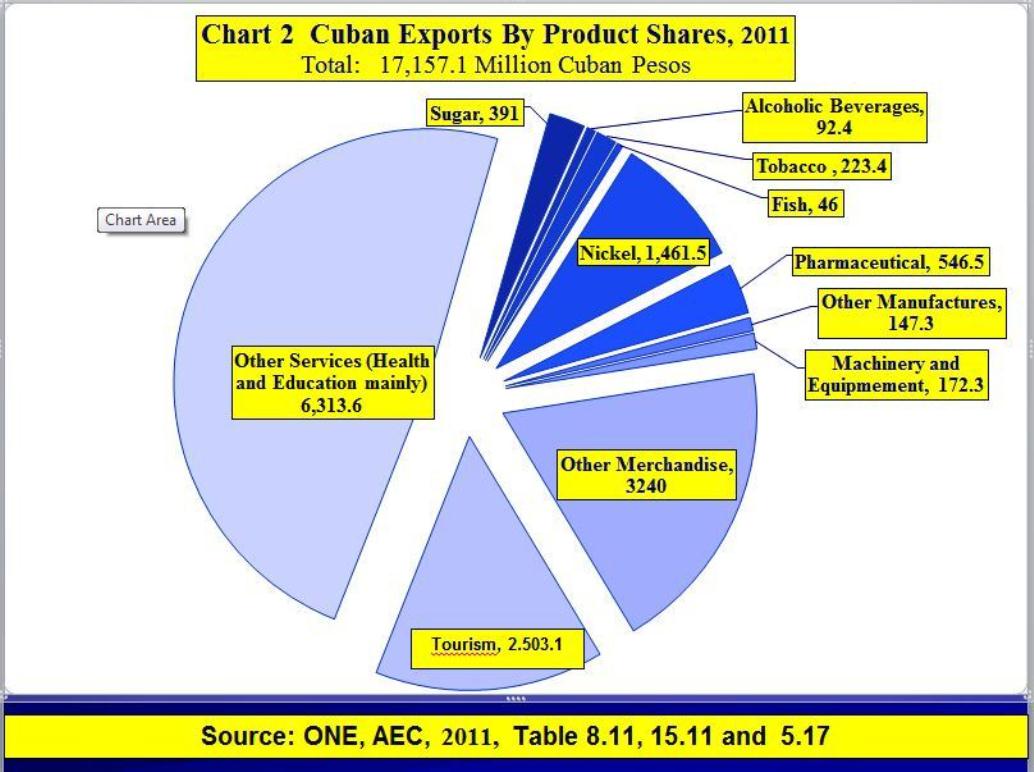

Since 1989, and similar to the United States and Canada among other countries, Cuba has experienced a serious de-industrialization from which it has not recovered. The consequences of this are grave, including job and income loss, the loss of an important part of its economic base and rust-belt style urban decay. Cuba risks becoming a typical small Caribbean Island, exporting services and some resources, while importing almost all manufactures.[i]

The causes of the collapse are complex and multi-dimensional. They were outlined in an earlier article available here: Can Cuba Recover from its De-Industrialization? I. Characteristics and Causes. In summary, the causes include:

The causes of the collapse are complex and multi-dimensional. They were outlined in an earlier article available here: Can Cuba Recover from its De-Industrialization? I. Characteristics and Causes. In summary, the causes include:

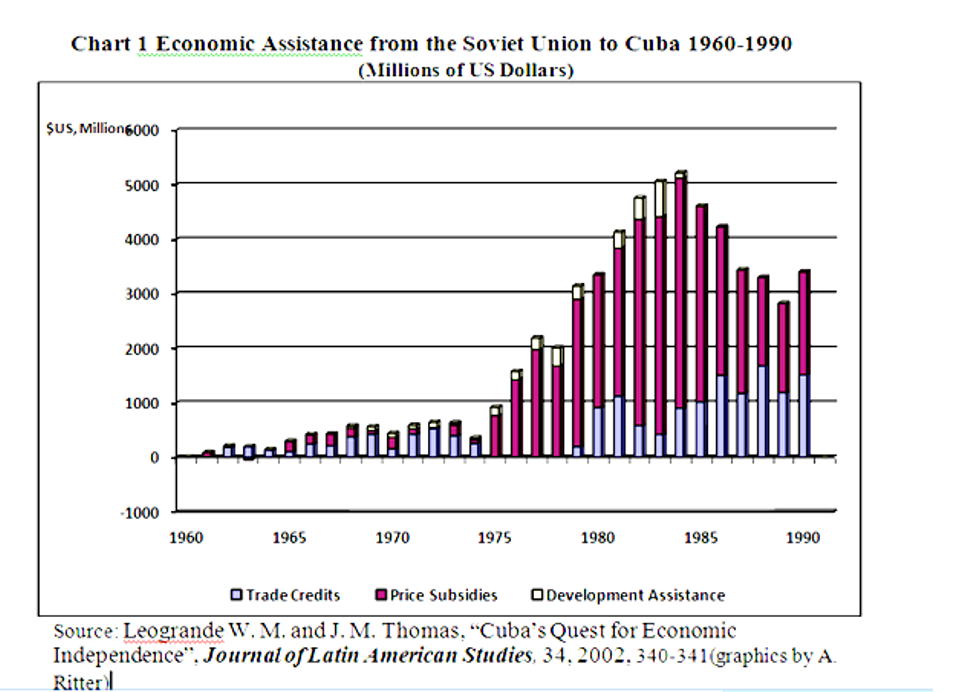

- The ending of the subsidization from the Soviet Union resulting in an incapacitation of the manufacturing sector;

- The antiquated and uncompetitive technological inheritance from the Soviet era;

- Maintenance and re-investment was de-emphasized before 1989 and collapsed thereafter;

- Low investment levels. [Investment was 10.5% of GDP in 2008 in comparison with 20.6% for all of Latin America, according to UN ECLA];

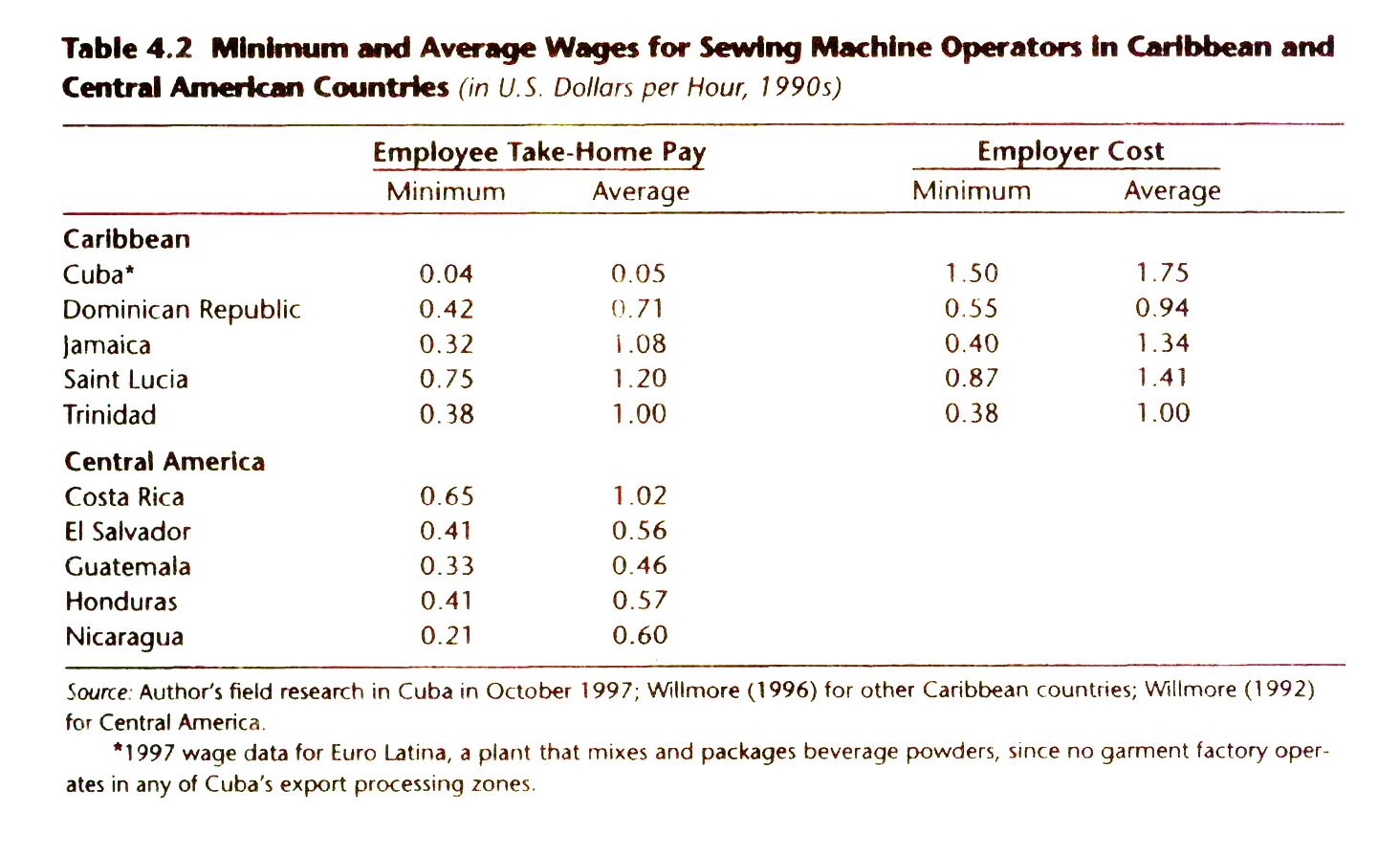

- The dual monetary and exchange rate systems penalize traditional and potential new exporters that have received Moneda Nacional pesos at a rate of CuP 1 = $US 1.00 from exports – while the relevant rate for Cuban citizens is 26 CuP = $US1.00;

- The prohibition of most small and medium enterprise for the last 50 years has blocked entrepreneurial trial and error and the emergence of new manufacturing activities;

- Effective competition from Chinese manufactures imports, stimulated further by China’s undervalued exchange rate and Cuba’s over-valued exchange rate.

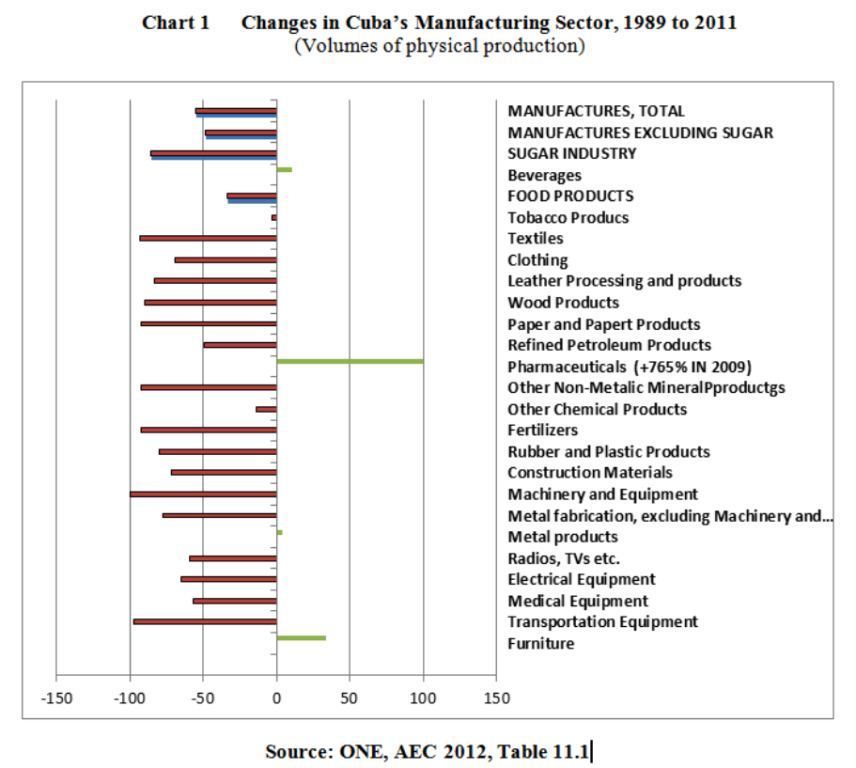

The accompanying chart illustrates the changes that have occurred Cuban manufacturing and some of its subsectors. Total manufacturing output excluding sugar in 2011 was 48.8% below the level of 1989 in terms of physical volumes. Many sectors experienced reductions in the 50% to 99% range. The exceptional success was pharmaceutical production which increased by 765% from 1989 to 2009, albeit from a low base.

What are the longer term consequences of “de-industrialization”? Is it likely that the policy proposals of the Lineamientos approved at the VI Congress of the Communist Party of Cuba will lead to a recovery from this collapse? What can be done to reverse this situation?

I. CONSEQUENCES OF THE COLLAPSE OF CUBA’S MANUFACTURING SECTOR

The consequences of the shrinkage of the manufacturing sector are serious. First, employment in the sector (including sugar) declined from 685,500 in 1989 to 530,800 in 2009 or to 77.4% of the 1989 level, a reduction of 32.6%. (ONE AEC, 2011 Table 7.3)

Second, labor productivity in manufacturing has fallen. The volume of output has diminished more rapidly than employment. The 2009 level of output in the manufacturing sector (including sugar) was 44.9% of the 1989 level (a decline of 55.1%) but employment declined by 32,6%. This means that labor productivity in manufacturing has also probably declined from 1989 to 2009, though this cannot be known for sure without knowing the values as well as the volumes of production in these years.

Third, the importation of manufactures has risen sharply. Virtually all the shoes, clothing, textiles, household gadgetry and a lot of furniture are now imported. Indeed, one can purchase most plumbing supplies, electrical materials, dishes, pots and pans, household gadgetry and furnishings only for “Convertible Pesos” rather than the Moneda Nacional that people actually earn.

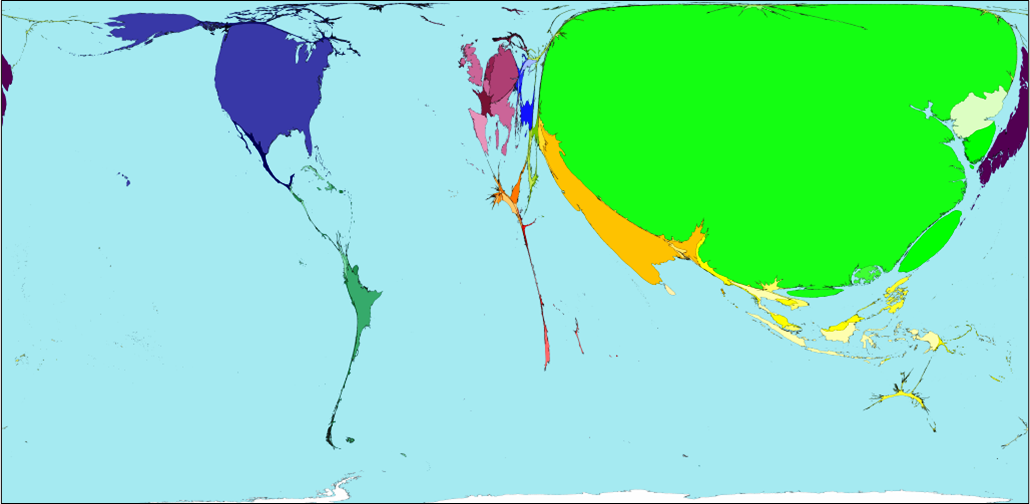

Paradoxically, visits to the various Tiendas por la Recaudacion de Divisas (TRDs or former dollar stores) which are the main source of household equipment and gadgetry, furnishings, clothing, foot-ware, plumbing materials, electrical items etc. is similar in one sense to visits to the major Big Box stores such as Walmart or Target in that the vast majority of the items for sale are imported from China. Walmart, Home Depot, Target and their ilk, make their mammoth purchases from China for all their stores in the country, obtaining massive economies of scale and quantity discounts. Has the China-Walmart Alliance helped to de-industrialized the United States?

One wonders if the procurement patterns for the large state store chains in Cuba are not unlike those of Walmart, pictured below. Does CIMEX, the major retailing conglomerate in Cuba make its purchases in the same way, providing for all its outlets in Cuba with single orders? Is a CIMEX-China Alliance in Cuba echoing the China-Walmart Alliance in the United States and having similar results in avoiding smaller scale procurement purchases from Cuba or other countries?

The World According to Walmart’s Procurement Purchases

The World According to Walmart’s Procurement Purchases

(One wonders if CIMEX procurement would be somewhat similar.)

A fourth result of Cuba’s de-industrialization is that it has lost much of the foundation on which diversified manufacturing activities could be developed in future. For example, Cuba has essentially lost the “clusters” of economic activities that once surrounded the sugar sector specifically and agriculture generally producing inputs and processing outputs. Parts of the sugar-related manufacturing sector have largely shut down – notably the manufacture of cane harvesters and agricultural machinery and equipment as well as the production of replacement parts for the sugar mills. As illustrated in Chart 1, the production of machinery and equipment is at 0.4% of the 1989 level while that for metal fabrication is at 32.8%.

This situation prevails in many other areas of manufacturing as well. A glance at the Chart indicates the magnitudes of the collapse.

Fifth, the potential for the emergence of manufacturing for export markets has been impaired. It will be difficult to reconstruct the manufacturing activities for which Cuba might have been able to develop some comparative advantages.

II. THE “LINEAMIENTOS” ON THE MANUFACTURING SECTOR.

The “Lineamientos de la Política Económica y Social del Partido y la Revolución,” approved on April 18, 2011 by the VI Party Congress include 25 guidelines on Industry. (Lineamientos de la Política Económica y Social del Partido y la Revolución.) Some of the guidelines are of obvious significance and would be of great usefulness if they can be implemented. These include

- “prioritizing” exports (Guideline No. 215) and maintenance (220),

- assuring inputs for the self-employment and cooperative sectors (217),

- emphasizing technical training ((132 and 138)

- the rationalization and restructuring of industrial capacity, including the sales, rental or usufruct of unused facilities to the self-employed (219).

Some specific industrial sectors are slated for emphasis, including pharmaceuticals (221(, nickel (224), natural medicines and dietary supplements (222) , information technology and electronics for export (226), fertilizers (230), rubber tires (231), construction materials (233), and metallurgy and machinery and equipment (234 236 and 237). Some of these seem reasonable and may have important roles to play in future manufacturing.

Elsewhere in the “Lineamientos” exchange rate and pricing considerations are mentioned, with the stated intention to move to a unified and realistic exchange rate but with no implementation as of September 2013.

Liberalizing small enterprise and promoting larger co-operative forms of organization are now in process of implementation. For these two sectors, pricing is for the most part to be determined by the forces of supply and demand. This may be an important step in permitting the emergence of new innovative enterprises. However, the continuing limits on size and professional activities impede the evolution of a diversified range of medium scale enterprise in higher tech manufacturing and related services.

If indeed the proposals of the “Lineamientos” were implemented fully and quickly, one could envisage the possibility of a turn-around for the manufacturing sector. So far, however, reforms in these areas have been cautious limited and slow.

III. SOME POSSIBILITIES

What might be the successful manufacturing sub-sectors in future? This section briefly considers some possibilities.

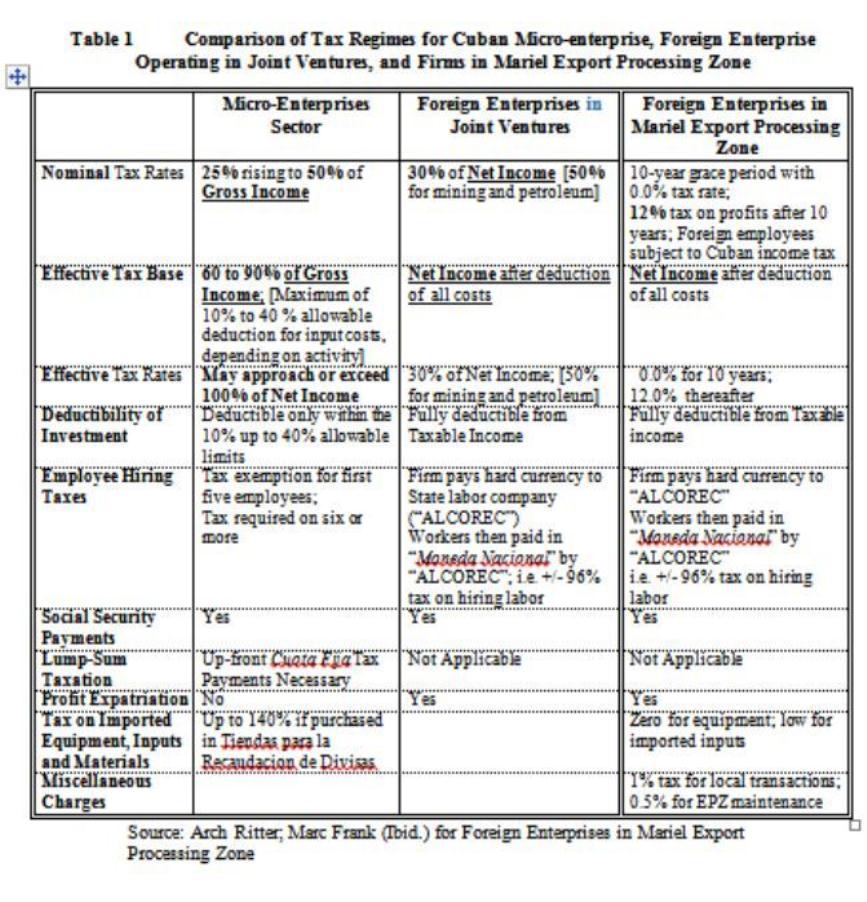

It is of course hard if not impossible to “pick the winners” in advance. The most efficacious general approach for Cuba would be to establish a reasonable policy and institutional framework and let the winners emerge over time. This would include such policies as unifying the monetary and exchange rate systems, liberalizing small and medium enterprise further, establishing a secure property rights system, consolidating the framework for the impartial rule of law towards enterprises, and a fair taxation system for Cuban-owned private sector enterprises, etc. (See The Tax Regimen for the Mariel Export Processing Zone.regarding the unfairness of the tax system as regards Cuban-owned micro-enterprises.) Cuba is in the process of implementation in some of these areas though it still has a distance to go.

However, assuming that Cuba does establish an “enabling environment” for the emergence of a manufacturing sector, what might be the manufacturing opportunities for Cuba? This section tries to make a first sketch of Cuba’s main manufacturing sub-sectors and their future potential.

A. Traditional Agro-Industries: Sugar, Tobacco and Rum.

The volumes of output in the sugar agro-industrial sector fell from 7 to 8 million metric tons of sugar per year in the 1980s to 1.8 million for the 2013 harvest. Perhaps the sector, focusing also on bio-fuels, can be reconstructed although now this would have to be almost from the ground up. Foreign – that is, Brazilian – technology, investible resources, managerial talent and entrepreneurship would be vital in this endeavor. But the old dysfunctional state enterprise model seems so entrenched that only successful implementation of dramatic institutional change as well as massive investment can bring it about.

Cuba has a major comparative advantage in cigars and a thriving agricultural and manufacturing base for future expansion. Market prospects are mixed but modestly positive on balance. The market for cigars in the high income countries may weaken in future as the baby boomers age further and become more concerned about their health. The cigar fad of the 1990s is unlikely to return in those countries with the same intensity.

On the other hand, cigars may become a status symbol for the males of the burgeoning middle classes of the emerging middle income countries of Latin America and Asia. Normalization of relations with the US will also increase demand.

Conclusion? Continue to promote this sector. Also a suggestion: produce for export high quality but machine-made cigars at prices that are more affordable for a broader market. Cuba has priced itself out of the middle class cigar market.

The market for rum and alcoholic beverages has been strong. Its future should also be positive again due to increasing demand in emerging countries and the United States after normalization.

B. Food Processing

Cuba should have great potential in processing agricultural products. However, this depends on a thriving agricultural sector providing the raw materials. Unfortunately agriculture has been in steady decline especially since 1990. Some past exports such as citrus fruit have fallen out of the picture.

Cuba could have significant production for export markets of citrus products, tropical fruits, vegetables, and beverages. This would require major expansion of food production and is thus a longer-term possibility at this time. However, a a diversified range of agro-industrial possibilities could be considered, e.g. mango cultivation and juicing for export markets. [ii]

C. Pharmaceuticals.

This sector has been dramatically successful since 1989, and has become a major export exporter to a growing range of countries. (See the accompanying chart.) This success should continue into the future.

However there are some downside risks. First, new drugs must continuously be developed because generic versions of existing drugs can be produced freely anywhere (read India and China) when patent protection runs out – if not before. This means that Cuba’s producers, like big pharmaceutical companies, face future death unless they innovate successfully. Second, some of the markets for Cuba’s pharmaceuticals are a type of ideological “sweet-heart” deal, e.g. purchases by Venezuela. These may be at risk in the longer term when the Cuba-Venezuela “special relationship” runs its course.

D. Light Manufactures

Some of the economic activities that have declined most seriously – from 70% to 90% in different cases – are footwear, textiles, clothing, and consumer products of leather, wood, paper, metal, rubber and plastic for household use (See Chart 1.) This seems tragic when one considers that even in the 1940’s, Cuba was a major producer of a range of products such as leather and rubber shoes, cotton and rayon textiles, rubber tires, soap, paint, clothing etc. (IBRD, Report on Cuba 1950, p.130.) The collapse of much of Cuba’s light industry is of course paralleled by its corresponding collapse in Canada and the United States, with the resultant job-loss and urban decay in the rust-belt.

It would be difficult for Cuba to reclaim many of these areas, given the incredible economies of scale and agglomerative economies that big countries such as China, India, and other Asian countries experience.

One can imagine niche-type markets for which Cuba could have success. For example, the manufacture of some lines of specialty women’s clothing, leather footwear, and Spanish-colonial style furniture might be possibilities. Already one sees surprising crafts-level innovation in a myriad of areas, focusing on hard-currency tourist markets. These provide some hope that middle-sized enterprises could emerge and develop new products for Cuban and foreign markets.

But for this to happen there would have to be the possibility that micro-enterprises could evolve into small and medium scale firms. This is still blocked – with the exception of cooperative forms of enterprises.

E. Chemical and Petrochemical Products.

If Cuba emerges as a significant petroleum producer or refiner of petroleum imports, it is possible that it may develop a range of petrochemical products for national and regional markets. Some production and exports are likely to emerge from the new refinery complex in Cienfuegos. However, the competition in the region from established producers in the region such as the US gulf coast, Mexico, Trinidad and Venezuela is serious so the possibilities here seem limited.

Could the production or “mixing” of fertilizers – from imported potash, phosphates and nitrogen – be revived? Perhaps, though Cuba has no particular advantage in this area.

F. Heavy Industry and Capital Goods Production

Heavy industry such as an iron and steel complex, metal fabrication, wire and tube making is unlikely to emerge in a significant way in Cuba due to lack of cheap energy sources at this time, the absence of relevant raw materials, absence of significant metal using industries within Cuba, the small domestic market vis-à-vis efficient scales of production, absence of relevant skills etc. This situation could change in future if low-cost sources of energy from off-shore petroleum were to be developed.

H. Machinery and Equipment

Cuba has produced some agricultural transport equipment, namely cane carts, since early colonial times. More recently, it produced heavy can harvesters such as the one in the adjoining photograph.

At this time, Cuba has lost the agricultural foundation for the production of machinery and equipment for the agricultural sector, though there may be some niches where possibilities exist. Brazil seems likely to capture much of this market. There may be some niche products that could emerge however.

Chances for Cuba of capturing automotive parts, batteries, rubber tires etc. seem slim and assembly is out of the question given the lack of the relevant cluster of economic activities on which these would be based and the great economies of scale in established producers elsewhere.

I. Electric and Electronic Equipment

The assembly of some electric or electronic products occurs now in a minor way and could perhaps be expanded. However, virtually all of the components would have to be imported so that domestic value added would be limited. Again, competition from abroad, notably from China will be difficult to overcome due to its huge advantages noted earlier.

J. The Mariel Export Processing Zone

The Mariel EPZ creates some new possibilities for Cuba. It is possible that China (being wooed by Cuba with a “Mariel mission” visiting that country in September 2013), Brazil and possibly other countries establish assembly, light fabrication or bulk-breaking activities in the EPZ. This is certainly the purpose of the highly generous tax treatment provided to foreign investors, namely a “Zero” profits tax rate for 10 years with presumably full expatriation of profits and a rate of 12.5% after 10 years. (See The Tax Regimen for the Mariel Export Processing Zone.)

IV. CONCLUSION

To revive Cuba’s manufacturing sector will be difficult. The loss of so much industrial capacity over the last quarter Century has weakened the foundation on which such a recovery could be based. There are a few promising sectors, most notably pharmaceuticals, food products, and some niche fabrication activities. But other most sub-sectors appear generally to be un-promising. Perhaps the Mariel Export Processing Zone will have some beneficial impacts.

What is most needed is the establishment of an “enabling environment” of company law, liberalization of small and medium enterprise, a reasonable tax regimen for Cuban private sector enterprises and of the monetary and exchange rate systems. Some of this was recognized in the “Lineamientos.” But there is still some distance to go.

Cuban-Manufactured Cane-Harvester Pausing on the Highway, November 1994; Photo by Arch Ritter. Was thuis the last Cuban-made Harvester?

Cuban-Manufactured Cane-Harvester Pausing on the Highway, November 1994; Photo by Arch Ritter. Was thuis the last Cuban-made Harvester?[i] The industrial sector has not yet been examined as in as much depth as some other economic areas such as agriculture. However, analysts at the Centro de Estudios sobre la Economia Cubana (CEEC) in Havana, notably Ricardo Torres Perez, have been turning their attention to this area.

[ii] For example, Canada imports growing volumes of several varieties of mango juice from the Republic of South Africa. Cuba could share in such markets. Again, normalization with the United States in time will be of benefit in providing a large near-by market.