COMPLETE DOCUMENT: Foro Cubano – Indicadores

Coordinador: Pavel Vidal Alejandro

BY NORA GÁMEZ TORRES

Miami Herald, July 10, 2018 07:01 PM

The Cuban government announced that it will start issuing licenses to open new businesses — frozen since August 2017 — but established greater controls through measures intended to prevent tax evasion, limit wealth and give state institutions direct control over the ‘self-employment’ sector

Original Article: TAXES, CONTROLS, CENSORSHIP

The Cuban government issued new measures on Monday to limit the accumulation of wealth by Cubans who own private businesses on the island. The provisions stipulate that Cubans may own only one private enterprise, and impose higher taxes and restrictions on a spectrum of self-employment endeavors, including the arts.

The government announced that it will start issuing licenses to open new businesses — frozen since last August — but established greater controls through a package of measures intended to prevent tax evasion, limit wealth and give state institutions direct control over the so-called cuentapropismo or self-employment sector.

The measures will not be immediately implemented. There is a 150-day waiting period to “effectively implement” the new regulations, the official Granma newspaper reported.

Cubans who run private restaurants known as paladares, for example, will not be able to rent a room in their home to tourists since no citizen can have more than one license for self-employment.

“There are workers who have a cafeteria and at the same time have a manicure or car wash license. … That is not possible. In practice, he is an owner who has many businesses, and that is not the essence and the spirit of the TCP [self-employment], which consists of workers exercising their daily activities,” Marta Elena Feitó Cabrera, vice minister for labor and social security, told the official Cubadebate site.

About 9,000 people, half in Havana, are affected by the measure, said the official.

In addition, all private sector workers must open an account in a state bank to carry out all their business operations. And the boteros, those who work as private taxi drivers, must present receipts to justify all their deductible expenses. Other measures curb the hiring of workers in the private sector, which currently employs 591,456 people, or 13 percent of the country’s workforce.

The government also stated it would eliminate the tax exemption for businesses that have up to five employees and would instead impose a sliding scale that increases with each worker hired. It also ordered an increase in the required minimum monthly taxes of businesses in various categories.

Government officials quoted by Granma said that the measures will increase tax collection and reduce fraud. But economists have warned that more taxes on hiring employees could dramatically hamper the development of the private sector at a critical moment. A monetary reform — which could bankrupt nearly half of the state companies, potentially leaving thousands unemployed — is expected to happen soon.

The new measures also maintain a halt on new licenses for things such as “seller vendor of soap” and “wholesaler of agricultural products,” among others.

One significant provision states that those who rent their homes to tourists and nationals may also rent to Cuban or foreign companies but “only for the purpose of lodging.” That would presumably prevent renters from subletting units.

The “rearrangement” of self-employment, as the new measures were framed in the official media, reduces licenses by lumping together various elements of one industry while limiting another. For example, while there would be only one license for all beauty services, permits for “gastronomic service in restaurants, gastronomic service in a cafeteria, and bar service and recreation” were separated — meaning that one can own a restaurant but not also a bar.

To increase controls, each authorized activity will be under the supervision of a state ministry, in addition to the municipal and provincial government entities, which can intervene to set prices. The level of control reaches such extremes that the Official Gazette published a table with classifications on the quality of public restrooms and the leasing rates that would have to be paid by “public bathroom attendants,” one of the authorized self-employment categories. Some public bathrooms are leased by the state to individuals who then are responsible for upkeep and make their money by charging users a fee.

The regulations are the first significant measures announced by the government since Miguel Díaz-Canel was selected as the island’s new president in April. But the proposed regulations had been in the making for months by different government agencies, according to a draft of the measures previously obtained by el Nuevo Herald. The announcement comes just as the Cuban economy is struggling to counter the losses brought by the crisis in Venezuela — its closest ally — and the deterioration of relations with the United States.

The new measures could also have a significant impact on the cultural sector. The decree may be used by the Ministry of Culture to increase control over artists and musicians and impose more censorship in the country.

Decree 349 of 2018 establishes fines and forfeitures, as well as the possible loss of the self-employment license, to those who hire musicians to perform concerts in private bars and clubs as well as in state-owned venues without the authorization of the Ministry of Culture or the state agencies that provide legal representation to artists and musicians.

Many artists in urban genres such as reggaeton and hip-hop, who have been critical of the Cuban government, do not hold state permits to perform in public. However, many usually perform in private businesses or in other venues.

Painters or artists who sell their works without state authorization also could be penalized.

The measures impose sanctions on private businesses or venues that show “audiovisuals” — underground reggaeton videos or independent films, for example — that contain violence, pornography, “use of patriotic symbols that contravene current legislation,” sexist or vulgar language and “discrimination based on skin color, gender, sexual orientation, disability and any other injury to human dignity.”

The government will also sanction state entities or private businesses that disseminate music or allow performances “in which violence is generated with sexist, vulgar, discriminatory and obscene language.”

Even books are the target of new censorship: Private persons, businesses and state enterprises may not sell books that have “contents that are harmful to ethical and cultural values.”

Some CuentaPropistas:

Boulder, CO: First Forum Press, 2015. 373 pp.

By Archibald R. M. Ritter and Ted A. Henken

Review by Sergio Díaz-Briquets,

Cuban Studies, Volume 46, 2018, pp. 375-377, University of Pittsburgh Press

The small business sector, under many different guises, often has been, since the 1960s, at the center of Cuban economic policy. In some ways, it has been the canary in the mine. As ideological winds have shifted and economic conditions changed, it has been repressed or encouraged, morphed and gone underground, surviving, if not thriving, as part of the second or underground economy. Along the way, it has helped satisfy consumer needs not fulfilled by the inefficient state economy. This intricate, at times even colorful, trajectory has seen the 1968 Revolutionary Offensive that did away with even the smallest private businesses, modest efforts to legalize self-employment in the 1979s, the Mercados Libres Campesinos experiment of the 1980s, and the late 1980s ideological retrenchment associated with the late 1980s Rectification Process.

The small business sector, under many different guises, often has been, since the 1960s, at the center of Cuban economic policy. In some ways, it has been the canary in the mine. As ideological winds have shifted and economic conditions changed, it has been repressed or encouraged, morphed and gone underground, surviving, if not thriving, as part of the second or underground economy. Along the way, it has helped satisfy consumer needs not fulfilled by the inefficient state economy. This intricate, at times even colorful, trajectory has seen the 1968 Revolutionary Offensive that did away with even the smallest private businesses, modest efforts to legalize self-employment in the 1979s, the Mercados Libres Campesinos experiment of the 1980s, and the late 1980s ideological retrenchment associated with the late 1980s Rectification Process.

Of much consequence—ideologically and increasingly economically—are the policy decisions implemented since the 1990s by the regime, under the leadership of both Castro brothers. Initially as part of Special Period, various emergency measures were introduced to allow Cuba to cope with the economic crisis precipitated by the collapse of the communist bloc and the end of Soviet subsidies. These early, modest entrepreneurial openings were eventually expanded as part of the deeper institutional reforms implemented by Raúl upon assuming power in 2006, at first temporarily, and then permanently upon the resignation of his brother as head of the Cuban government.

In keeping with the historical zigzag policy pattern surrounding small businesses activities—euphemistically labeled these days as the “non-state sector”—while increasingly liberal, they have not been immune to temporary reversals. Among the more significant reforms were the approval of an increasing number of self-employment occupations, gradual expansion of the number of patrons restaurants could serve (as dictated by the allowed number of chairs in privately owned paladares), and the gradual, if uneven, relaxation of regulatory, taxing, and employment regulations. Absent has been the authorization for professionals (with minor exceptions, such as student tutoring) to privately engage in their crafts and the inability to provide wholesale markets where self-employed workers could purchase inputs for their small enterprises.

The authors of this volume, an economist and a sociologist, have combined their talents and carefully documented this ever-changing policy landscape, including the cooperative sector. They have centered their attention on post–Special Period policies and their implications, specifically to “evaluate the effects of these policy changes in terms of the generation of productive employment in the non-state sector, the efficient provision of goods and services by this emergent sector, and the reduction in the size and scope of the underground economy” (297).

While assessing post-1990 changes, Entrepreneurial Cuba also generated a systematic examination of the evolution of the self-employment sector in the early decades of the revolution in light of shifting ideological, political, and economic motivations. Likewise, the contextual setting is enhanced by placing Cuban self-employment within the broader global informal economy framework, particularly in Latin America, and by assessing the overall features of the second economy in socialist economies “neither regulated by the state nor included in its central plan” (41). These historical and contextual factors are of prime importance in assessing the promise and potential pitfalls the small enterprise sector confronts in a changing Cuba.

Rich in its analysis, the book is balanced and comprehensive. It is wide ranging in that it carefully evaluates the many factors impinging on the performance of the small business sector, including their legal and regulatory underpinnings. The authors also evaluate challenges in the Cuban economic model and how they have shaped the proclivity for Cuban entrepreneurs to bend the rules. Present is a treatment of the informal social and trading networks that have sustained the second economy, including the ever-present pilfering of state property and the regulatory and transactional corruption so prevalent in Cuba’s centralized economy.

While none of the above is new to students of the Cuban economy—as documented in previous studies and in countless anecdotal reports—Ritter and Henken make two major contributions. First, they summarize and analyze in a single source a vast amount of historical and contemporary information. The value of the multidisciplinary approach is most evident in the authors’ assessment of how the evolving policy environment has influenced the growth of paladares, the most important and visible segment of the nonstate sector. By focusing on this segment, the authors validate and strengthen their conclusions by drawing from experiences documented in longitudinal, qualitative case studies. The latter provide insights not readily gleaned from documentary and statistical sources by grounding the analysis in realistic appreciations of the challenges and opportunities faced by entrepreneurial Cubans. Most impressive is the capacity of Cuban entrepreneurs to adapt to a policy regime constantly shifting between encouraging and constraining their activities.

Commendable, too, is the authors’ balanced approach regarding the Cuban political environment and how it relates to the non-state sector. Without being bombastic, they are critical of the government when they need to be. One of their analytical premises is that the “growth of private employment and income represents a latent political threat to state power since it erodes the ideals of state ownership of the means of production, the central plan, and especially universal state employment” (275).

This dilemma dominates the concluding discussion of future policy options. Three scenarios are considered possible. The first entails a policy reversal with a return to Fidel’s orthodoxy. This scenario is regarded as unlikely, as Raúl’s policy discourse has discredited this option. A second scenario consists of maintaining the current course while allowing for the gradual but managed growth of the non-state sector. While this might be a viable alternative, it will have limited economic and employment generation effects unless the reform process is deepened by, for example, further liberalizing the tax and regulatory regimes and allowing for the provision of professional services.

The final scenario would be one in which reforms are accelerated, not only allowing for small business growth but also capable of accommodating the emergence of medium and large enterprises in a context where public, private, and cooperative sectors coexist (311). As Ritter and Henken recognize, this scenario is unlikely to come to fruition under the historical revolutionary leadership, it would have to entail the resolution of political antagonisms between Washington and Havana, and a reappraisal by the Cuban government of its relationship with the émigré population. Not mentioned by Ritter and Henken is that eventual political developments—not foreseen today—may facilitate the changes they anticipate under their third scenario.

In short, Entrepreneurial Cuba is a must-read for those interested in the country’s current situation. Its publication is timely not only for what it reveals regarding the country’s economic, social, and political situation but also for its insights regarding the country’s future evolution.

…………………………………………………………………………….

Table of Contents,

List of Charts and Figures

Chapter I Introduction

Chapter II Cuba’s Small Enterprise Sector in International and Theoretical Perspective

Chapter III Revolutionary Trajectories, Strategic Shifts, and Small Enterprise, 1959-1989

Chapter IV Emergence and Containment During the “Special Period”, 1990-2006

Chapter V The 2006-2011 Policy Framework for Small Enterprise under the Presidency of Raul Castro

Chapter VI The Movement towards Non-Agricultural Cooperatives

Chapter VII The Underground Economy and Economic Illegalities

Chapter VIII Ethnographic Case Studies of Microenterprise, 2001 vs. 2011

Chapter IX Summary and Conclusions

APPENDIX

GLOSSARY

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Stuck in the past: The revolutionary economy is neither efficient nor fun.

The Economist, April 1, 2017

Original Article: STUCK IN THE PAST

TOURISTS whizz along the Malecón, Havana’s grand seaside boulevard, in bright-red open-topped 1950s cars. Their selfie sticks wobble as they try to film themselves. They move fast, for there are no traffic jams. Cars are costly in Cuba ($50,000 for a low-range Chinese import) and most people are poor (a typical state employee makes $25 a month). So hardly anyone can afford wheels, except the tourists who hire them. And there are far fewer tourists than there ought to be.

Hotel at Vinales; apparently constructed with Mafia money as part of their major money-laundering 1950s tourism investment project. (Photo by Arch Ritter, 2015)

Hotel at Vinales; apparently constructed with Mafia money as part of their major money-laundering 1950s tourism investment project. (Photo by Arch Ritter, 2015)

Few places are as naturally alluring as Cuba. The island is bathed in sunlight and lapped by warm blue waters. The people are friendly; the rum is light and crisp; the music is a delicious blend of African and Latin rhythms. And the biggest pool of free-spending holidaymakers in the western hemisphere is just a hop away. As Lucky Luciano, an American gangster, observed in 1946, “The water was just as pretty as the Bay of Naples, but it was only 90 miles from the United States.”

There is just one problem today: Cuba is a communist dictatorship in a time warp. For some, that lends it a rebellious allure. They talk of seeing old Havana before its charm is “spoiled” by visible signs of prosperity, such as Nike and Starbucks. But for other tourists, Cuba’s revolutionary economy is a drag. The big hotels, majority-owned by the state and often managed by companies controlled by the army, charge five-star prices for mediocre service. Showers are unreliable. Wi-Fi is atrocious. Lifts and rooms are ill-maintained.

Despite this, the number of visitors from the United States has jumped since Barack Obama restored diplomatic ties in 2015. So many airlines started flying to Havana that supply outstripped demand; this year some have cut back. Overall, arrivals have soared since the 1990s, when Fidel Castro, faced with the loss of subsidies from the Soviet Union, decided to spruce up some beach resorts for foreigners (see chart). But Cuba still earns less than half as many tourist dollars as the Dominican Republic, a similar-sized but less famous tropical neighbour.

But investment in new rooms has been slow. Cuba is cash-strapped, and foreign hotel bosses are reluctant to risk big bucks because they have no idea whether Donald Trump will try to tighten the embargo, lift it or do nothing. On the one hand, he is a protectionist, so few Cubans are optimistic about his intentions. On the other, pre-revolutionary Havana was a playground where American casino moguls hobnobbed with celebrities in raunchy nightclubs. Making Cuba glitzy again might appeal to the former casino mogul in the White House.

The other embargo is the many ways in which the Cuban state shackles entrepreneurs. The owner of a small private hotel complains of an inspector who told him to cut his sign in half because it was too big. He can’t get good furniture and fixtures in Cuba, and is not allowed to import them because imports are a state monopoly. So he makes creative use of rules that allow families who say they are returning from abroad to repatriate their personal effects (he has a lot of expat friends). “We try to fly low under the radar, and make money without making noise,” he sighs.

Cubans with spare cash (typically those who have relatives in Miami or do business with tourists) are rushing to revamp rooms and rent them out. But no one is allowed to own more than two properties, so ambitious hoteliers register extra ones in the names of relatives. This works only if there is trust. “One of my places is in my sister-in-law’s name,” says a speculator. “I’m worried about that one.”

Taxes are confiscatory. Turnover above $2,000 a year is taxed at 50%, with only some expenses deductible. A beer sold at a 100% markup therefore yields no profit. Almost no one can afford to follow the letter of the law. For many entrepreneurs, “the effective tax burden is very much a function of the veracity of their reporting of revenues,” observes Brookings, tactfully.

The currency system is, to use a technical term, bonkers. One American dollar is worth one convertible peso (CUC), which is worth 24 ordinary pesos (CUP). But in transactions involving the government, the two kinds of peso are often valued equally. Government accounts are therefore nonsensical. A few officials with access to ultra-cheap hard currency make a killing. Inefficient state firms appear to be profitable when they are not. Local workers are stiffed. Foreign firms pay an employment agency, in CUC, for the services of Cuban staff. Those workers are then paid in CUP at one to one. That is, the agency and the government take 95% of their wages. Fortunately, tourists tip in cash.

The government says it wants to promote small private businesses. The number of Cubans registered as self-employed has jumped from 144,000 in 2009 to 535,000 in 2016. Legally, all must fit into one of 201 official categories. Doctors and lawyers who offer private services do so illegally, just like hustlers selling black-market lobsters or potatoes. The largest private venture is also illicit (but tolerated): an estimated 40,000 people copy and distribute flash drives containing El Paquete, a weekly collection of films, television shows, software updates and video games pirated from the outside world. Others operate in a grey zone. One entrepreneur says she has a licence as a messenger but wants to deliver vegetables ordered online. “Is that legal?” she asks. “I don’t know.”

Cubans doubt that there will be any big reforms before February 2018, when Raúl Castro, who is 86, is expected to hand over power to Miguel Díaz-Canel, his much younger vice-president. Mr Díaz-Canel is said to favour better internet access and a bit more openness. But the kind of economic reform that Cuba needs would hurt a lot of people, both the powerful and ordinary folk. Suddenly scrapping the artificial exchange rate, for example, would make 60-70% of state-owned firms go bust, destroying 2m jobs, estimates Juan Triana, an economist. Politically, that is almost impossible. Yet without accurate price signals, Cuba cannot allocate resources efficiently. And unless the country reduces the obstacles to private investment in hotels, services and supply chains, it will struggle to provide tourists with the value for money that will keep them coming back. Unlike Cubans, they have a lot of choices.

SAIRA PONS PÉREZ, CEEC, University of Havana

Cuba Study Group, MAY 20, 2015

Original Article Here: Tax Law Dilemmas for Self-Employed Workers

In2010, a series of regulations were published that allowed for the expansion of self-employment as an alternative to the rationing of employment in the state sector and for the creation of goods and services for the population. In just over four years, the number of private enterprises grew threefold, going from 144,000 in 2009 to 490,000 people by the end of February 2015. Currently, self-employed workers known as “cuentapropistas” represent 8% of employment and generate 5% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), according to data from Cuba’s National Office of Statistics and Information (ONEI).

These changes were accompanied by new regulations in the tax arena1, which is the focus of this article. To understand them, it is necessary to take into consideration at least three basic elements. First, self-employed businesses are not recognized under the law as companies, even while no restrictions exist on the hiring of a labor force. This implies that all income is deemed as personal, and therefore subject to different liabilities than the profits of state or foreign companies, or cooperatives. It also means that it is not possible to apply specific deductions associated to investment, production costs, commercialization expenses or others typically associated with a company’s activities.

The second element is that the National Office of Tax Administration (ONAT) does not have the resources that would allow it to verify self-employed workers’ income and expenses case-by-case. Because of this, standardized methods are used, which is common around the world for the collection of revenue from small taxpayers.

Lastly, it is a principal objective of this special tax regime to avoid the private accumulation of property, in accordance with Guideline No. 3 of the 6th Party Congress. To put it another way, the tax system is beingused to discourage the growth of companies, imposing a progressive – and excessive- tax burden, as well as penalizing the hiring of more than five employees. These elements will be addressed in further detail ahead.

The structure of this article will be as follows: after the introduction, a section dedicated to a description of the special tax regime.

Continue reading: Tax Law Dilemmas for Self-Employed Workers

Mauricio A. Font y Mario González-Corzo, Editores, Con la asistencia de Rosalina López

New York: Bildner Center for Western Hemisphere Studies, The Graduate Center, The City University of New York, 2015

Documento Completo: Reformando el Modelo Economico Cubano

CONTENIDO

Introducción, Mario González-Corzo

Del ajuste externo a una nueva concepción del socialism Cubano, Juan Triana Cordoví

La estructura de las exportaciones de bienes en Cuba 29, Ricardo Torres

Relanzamiento del cuentapropismo en medio del ajuste structural, Pavel Vidal Alejandro y Omar Everleny Pérez Villanueva

Las cooperativas en Cuba, Camila Piñeiro Harnecker

La apertura a las microfinanzas en Cuba, Pavel Vidal Alejandro

Hacia una nueva fiscalidad en Cuba, Saira Pons

Bibliografía

The CENTRO DE ESTUDIOS DE LA ECONOMIA CUBANA has recently redone its web site. It has also published the Power Point presentations from its 2013 Seminar. Here is a list of the presentaions, hyper-linked on the author’s name.

The CENTRO DE ESTUDIOS DE LA ECONOMIA CUBANA has recently redone its web site. It has also published the Power Point presentations from its 2013 Seminar. Here is a list of the presentaions, hyper-linked on the author’s name.

Saira Pons Pérez, HACIA UNA NUEVA FISCALIDAD EN CUBA

Ricardo Torres Pérez, El desarrollo industrial cubano en un nuevo contexto

Juan Triana Cordoví, Cuba:un balance de la transformación.

Betsy Anaya Cruz , Cadenas productivas con impacto económico y social: el caso de los cítricos en Cuba

Aleida Gonzalez-Cueto, La Innovación y la administración de riesgos en las empresas cubanas en la actualidad

Orlando Gutiérrez Castillo, Reflexiones sobre los ambientes de innovación en las empresas cubanas

Anicia García y Betsy Anaya, Gastos básicos de una familia cubana urbana en 2011. Situación de las familias “estado dependientes”

Omar Everleny, Luisa Íñigues y Janet Rojas, Las escalas subnacionales de la macroeconomia cubana (pp.1-45)

Yailenis Mulet Concepción y Alejandro Louro, Las reformas económicas en los territories cubanos. Reflexiones para el diseño de políticas.

Jorge Ricardo Ramírez, Empresa cubana: Innovación, mejora continua de la calidad e integración

Dayma Echevarría León, Innovación social: experiencias desde un proyecto interasociativo en Camagüey

Humberto Blanco Rosales, GESTIÓN DE LA INNOVACIÓN (GI) : ESTUDIOS DE CASOS Y PROPUESTAS DE MEJORAMIENTO

Ileana Díaz Fernández, Desafios de la innovacion empresarial en Cuba

By Archibald Ritter

Cuba’s new Foreign Investment Law was published in the Gaceta Oficialon April 16, 2014. It is available here: Ley de la Inversión Extranjera

The objective of the law is to provide an improved legal, fiscal and regulatory framework for foreign enterprises that decide to operate in Cuba.

Cuba has passed this law because of the perceived benefits that such direct foreign investment can generate for the country, namely technological and managerial transfers, access to foreign markets, higher-productivity employment, higher income levels, financial inflows and increased levels of investment. This last factor is of especial importance in view of the very low levels of investment that Cuba has achieved for the last 20 years. Indeed Cuba’s levels of investment have been the lowest in all of Latin America for the last two decades. In 2011 this rate was 10.2% of GDP vis-a-vis 22.4% for all of Latin America. (UN CEPAL, Balance Preliminary, 2013).

The law certainly seems to have created a more hospitable environment for foreign firms, providing greater security of tenure, greater control over the hiring and compensation of labor, and most of all, through generous tax breaks. Indeed, the tax advantages for foreign investors now seem to me to be overly generous. One might estimate that the new foreign investment regime will be highly successful in promoting foreign investment from a range of sources and perhaps especially from China and Brazil.

However, there is a major element of injustice in the new law, particularly as it relates to taxation. The new tax regime intensifies the discrimination favoring foreign investors operating in “Mixed Enterprises” (Joint Ventures) or “international economic associations” when compared to the tax regime for small enterprises owned by Cuban citizens. This is both unfair and counterproductive. It may also be unsustainable.

The contrast between the tax treatment of foreign enterprises which will usually big private or (in the case of China) state corporations in comparison the tax treatment for small Cuban-owned firms, is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparison of the Tax Regimes for Cuban Small Enterprise and Foreign Enterprise Operating in Mixed Enterprises after the 2014 Foreign Investment Law

Small Enterprise Sector |

Foreign Investors in Mixed Enterprises or “Economic Associations” |

|

|

Nominal Tax Rates |

Personal Income Tax Rate: 15% rising to 50% of income above CuP 50,000 or $2,000 per year |

Profits Tax: 15% of Net Corporate Income [perhaps 50% for resources]; Personal Taxes Exempt for those earning profits. |

|

Effective Tax Base |

60 to 90% of Gross Revenues; [Maximum of 10% to 40 % allowable d for input costs, depending on activity] |

Net Income after deduction of all production and investment costs from Gross Revenues |

|

Effective Tax Rates |

May approach or even exceed 100% of Net Income |

15% of Net Income; [perhaps 50% for mining and petroleum] |

|

Tax Holiday |

None |

Eight Years Profit Tax Exemption, |

|

Deductibility ofInvestment Costs from Gross Revenues |

Deductible only within the 10% to 40% allowable deduction limits |

Fully deductible from Gross Revenues in determining Taxable Income |

|

Deductibility of Input Costs from Gross Revenues |

Deductible only within the 10% to 40% allowable deduction limits |

Fully deductible from Gross Revenues in determining Taxable Income |

|

Employee Hiring Tax |

Tax exemption for first five employees; Tax required on six or more |

Complete Tax Exemption |

|

Social Security Payments |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Lump-Sum Taxation |

Up-front Cuota Fija Tax Payments Necessary |

None |

|

Input Importation Rights |

Direct Import Purchases Prohibited |

Freedom to Import Directly |

|

Profit Expatriation |

No |

Yes |

The most obvious difference in tax treatment is that Cuban small enterprise operators pay a marginal tax rate of 50% of Gross Revenues (less deductions) on any income exceeding 50,000 pesos per year this being equivalent to about US$2,000.00 per year or about US 166.67 per month. In contrast, the foreign corporations in mixed enterprises pay 15% of Profits in taxes – but only after an eight year tax holiday.

Perhaps more serious, for Cuban small enterprise owners, taxable income is calculated as an arbitrary percentage of Gross Revenues – from 60% to 90% – depending on the nature of the economic activity. The costs of inputs of materials, labor, rent, utilities, etc. and all costs of investment are not deductible from Gross Revenues in determining Taxable Income – only the arbitrary amounts of 40 to 10% or Gross Revenues. To my knowledge, no other country taxes its own enterprise sector in this way.

On the other hand, foreign corporations can deduct all costs of investment and inputs of all sorts from Gross Income in calculating Taxable Income. This indeed is standard international practice.

Or in other words, the effective tax base for foreign firms is Gross Revenues minus all costs of production and investment. In contrast, for micro-enterprise the tax base is gross revenue minus arbitrary and limited maximum allowable levels of input costs ranging from 10 to 40 percent depending on the activity, regardless of true production costs.

The result of this is that the effective tax rates for foreign enterprises are reasonable though generous. But for Cuban small enterprises the effective tax rate can be unreasonable and could reach and exceed 100%. Moreover, investment costs are deductible from future income streams for foreign firms this being the normal international convention.

To add insult to injury, foreign investors receive an eight year tax holiday in which corporate profit taxes are exempt from taxation. Cuban citizens operating small enterprises receive no such tax holiday.

Moreover, under the new legislation, the profits of the foreign enterprises can all be repatriated. In contrast, the infinitely more modest after-tax incomes of Cuban citizens would virtually all be spent within the domestic economy. If their after-tax earnings were to be taken out of the country, they would have to exchange their CUP or Moneda Nacional savings for foreign currency at the rate of about CUP 26= $US1.00 or about CUP 34.5 = Euro 1.00

Small enterprise owners must make payment of a proportion of their taxes at the beginning of each month. Foreign firms certainly do not have to do this.

Small enterprise owners also must pay a tax on the hiring of more than five employees (not a good mechanism for creating jobs.). Foreign firms are exempt from such a tax.

Foreign firms can import their inputs, equipment and machinery as well as personnel directly from abroad. Cuban citizens with small enterprises must make their purchases from the state Tiendas por la Recaudacion de Divisas (formerly ‘Dollar Stores’)

This differential tax treatment for Cuban citizens operating small enterprises and foreign enterprises represents a surprising type of discrimination against Cuban citizens. One might predict that this type of discrimination will generate major dissatisfaction on the part of Cuban nationalists as well as Cuban small enterprise operators. Before long, political pressures and the climate of public opinion should require greater fairness in the character of taxation.

However, given the seemingly insurmountable difficulties that some countries such as the United States face in constructing fairer tax regimes, perhaps I am naively optimistic. (Who can forget the 15% average tax rate paid by Warren Buffett and the 14.3% paid by Mitt Romney in comparison with the 35% paid by Buffet’s secretary as well as the average US citizen?)

By Marc Frank

Original Article Here: Mariel

(Reuters) – Cuba published rules and regulations on Monday governing its first special development zone, touting new port facilities in Mariel Bay in a bid to attract investors and take advantage of a renovated Panama Canal.

The decree establishing the zone and related rules takes effect on Nov. 1 and includes significant tax and customs breaks for foreign and Cuban companies while maintaining restrictive policies, including for labor.

Cuba hopes the zone, and others it plans for the future, will “increase exports, the effective substitution of imports, (spur) high-technology and local development projects, as well as contribute to the creation of new jobs,” according to reform plans issued by the ruling Communist Party in 2011.

The plan spoke positively of foreign investment, promised a review of the cumbersome approval process and said special economic zones, joint venture golf courses, marinas and new manufacturing projects were planned. Most experts believe large flows of direct investment will be needed for development and to create jobs if the government follows through with plans to lay off up to a million workers in an attempt to lift the country out of its economic malaise.

The Mariel special development zone covers 180 square miles (466 square km) west of Havana and is centered around a new container terminal under construction in Mariel Bay, 28 miles (45 km) from the Cuban capital.

The zone will be administered by a new state entity under the Council of Ministers, and investors will be given up to 50-year contracts, compared with the current 25 years, with the possibility of renewal. They can have up to 100 percent ownership during the contract, according to Cuba’s foreign investment law.

Investors will be charged virtually no labor or local taxes and will be granted a 10-year reprieve from paying a 12 percent tax on profits. They will, however, pay a 14 percent social security tax, a 1 percent sales or service tax for local transactions, and 0.5 percent of income to a zone maintenance and development fund.

Foreign managers and technicians will be subject to local income taxes. All equipment and materials brought in to set up shop will be duty free, with low import and export rates for material brought in to produce for export.

However, one of the main complaints of foreign investors in Cuba has not changed: that they must hire and fire through a state-run labor company which pays employees in near worthless pesos while investors pay the company in hard currency.

Investors complain they have little control over their labor force and must find ways to stimulate their workers, who often receive the equivalent of around $20 a month for services that the labor company charges up to twenty times more for.

And investors will still face a complicated approval policy, tough supervision, and conflict resolution through Cuban entities unless stipulated otherwise in their contracts. And they must be insured through Cuban state companies.

MARIEL PORT

The Mariel container terminal and logistical rail and highway support, a $900 million project, is largely being financed by Brazil and built in conjunction with Brazil’s Grupo Odebrecht SA. The container facility will be operated by Singaporean port operator PSA International Pte Ltd. The terminal is scheduled to open in January.

Future plans call for increasing the terminal’s capacity, developing light manufacturing, storage and other facilities near the port, and building hotels, golf courses and condominiums in the broader area that runs along the northern coast and 30 miles (48 km) inland.

Mariel Bay is one of Cuba’s finest along the northern coast, and the port is destined to replace Havana, the country’s main port, over the coming years. The Mariel terminal, which will have an initial 765 yards (700 meters) of berth, is ideally situated to handle U.S. cargo if the American trade embargo is eventually lifted, and will receive U.S. food exports already flowing into the country under a 2000 amendment to sanctions.

Plans through 2022 call for Mariel to house logistics facilities for offshore oil exploration and development, the container terminal, general cargo and bulk foods facilities. Mariel Port will handle vessels with up drafts up to 49 feet (15 meters) compared with 36 feet (11 meters) at Havana Bay due to a tunnel under the channel leading into the Cuban capital’s port.

The terminal will have an initial capacity of 850,000 to 1 million containers, compared with Havana’s 350,000.

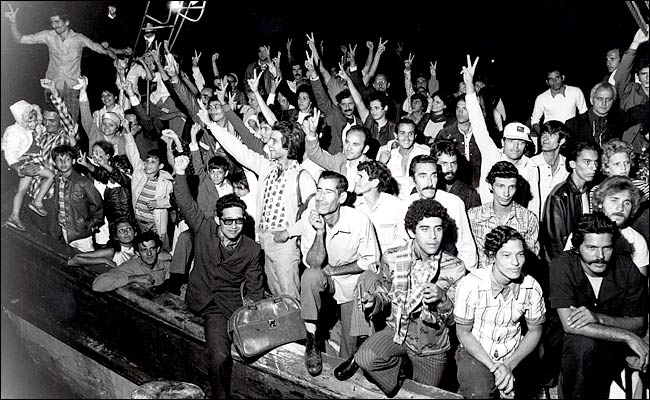

April 23, 1980: Arriving in Key West on the shrimp boat Big Babe.

April 23, 1980: Arriving in Key West on the shrimp boat Big Babe.

Dr. Juan Triana Cordoví, Universidad de la Habana

November 15, 2012

Submerged economy, merolicos, informal workers, cuentapropistas, self employed, a “necessary evil”, are some of the qualifiers used to describe individuals who work in the independent sector in Cuba closely reflects the fluctuations and reversals to which the non-state run economy has been exposed, and which in a way have been a thermometer for the transformations of the Cuban economy.

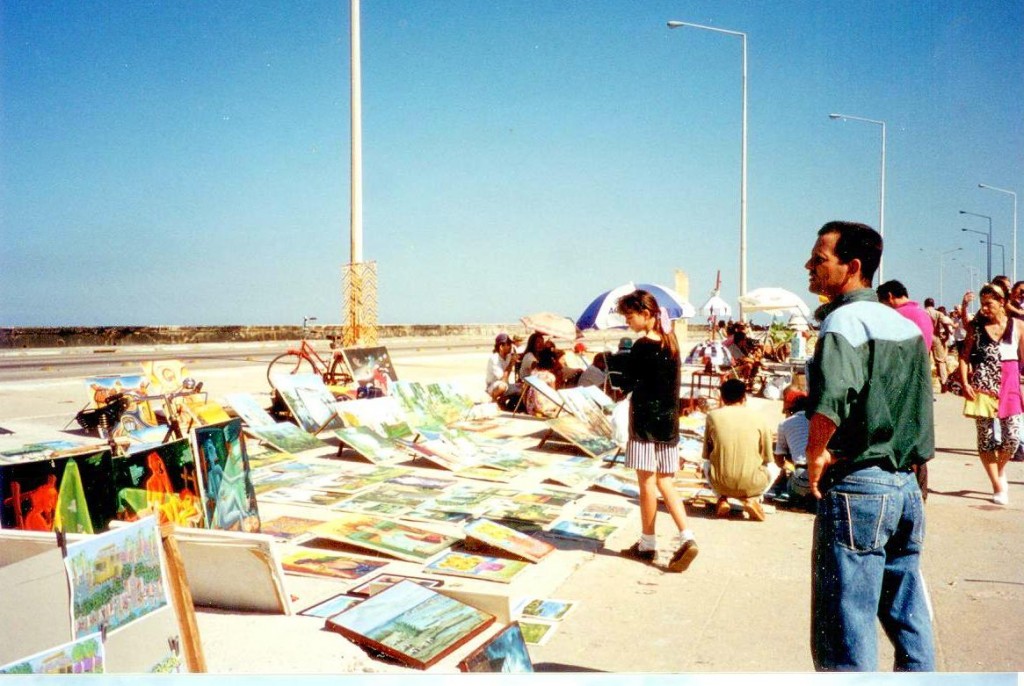

Art Market, on the Malecon. Photo by A. Ritter

Art Market, on the Malecon. Photo by A. Ritter

I. Some history: from the revolution to the rebirth of the independent work in 1993

As a result of the Cuban revolution in 1968, about 58,000 private businesses were nationalized, mostly small family businesses, focused on retail and restaurants. Some other small businesses worked in some kind of craft or industry, but these were generally low-tech. Some estimates put those businesses as employing between three and seven workers each. If we estimate an average of five workers per business, then the sector generated employment for about 300,000 people, out of a total population that exceeded six million.

Self-employment appeared when the different alternatives generated from the State failed to meet the demands of the population for different services and products (On July 3, 1978 Executive Order No. 14 was issued to regulate self-employment activities to be exercised by workers), but after a brief period of expansion, it languished in the absence of stimulus policies and its tacit rejection based on ideological and political considerations.

Self employment was revived in 19931 (Executive Decree 141) in response to the adjustments in the production and employment sectors generated by the crisis. It was accepted as a “necessary evil,” but not as an integral part of a development strategy destined to occupy a legitimate space to contribute to growth efforts 2.

Far from policies to stimulate and insert it in the operating dynamics of the economy, those policies helped to marginalize it, restrict it and prevent a qualitative transformation, which caused the decline of the sector (between 1996 and 2001 by 40%), its geographical concentration (especially in Havana) and concentration on the most profitable activities (food, transport and rentals)

That same policy that limited the access of new workers to the sector caused the generation and appropriation of undue rents, supported by the virtual monopoly in some market segments by those who “had come first,” into the sector and were later “protected” by the State. This was really ironic because the barriers to enter the sector that were created from the institutions that were supposed to “regulate” it, and the restrictive policies established, reduced competition in the “cuentapropista” sector, allowing the accumulation of income, not based on productivity and efficiency, as well as the expansion of informal channels of supply, some of them, hard to quantify, in many cases from state agencies, creating disincentives for improvement and innovation.

There were two big losers: the dynamics of the national economy, as an economic circuit was generated separately from the rest of the economy, and the population (clients) who debated between the government monopoly over some services, and the monopoly that almost unwittingly was exercised by portions of the self-employed over some (most lucrative) activities and services that were “unregulated”.

II. “Cuentapropismo” beyond “cuentapropismo”

Studies of this sector in Cuba, have often given priority to its importance for the economic liberalization and decentralization, as well as its significance from the point of view of the expansion of market relations. There is another perspective on this issue that also must be addressed. Micro, small and medium enterprises are part of the skein of any economy, regardless of the degree of development. Their contribution to employment is significant, the flexibility and maneuverability that it gives the economies (even developed economies) allowing systematic adjustments is unquestionable, and in some economies, this sector even has innovation capabilities that should not be ignored.

Until not very long ago, the “cuentapropista” sector in Cuba was a marginal sector, but this has drastically changed starting on 2011, and this trend should increase in the coming years.3

Table 1. Employment Dynamics

2008 2009 2010 2011

Total number of employed (thousands) 4.948,2 5.072,4 4.984,5 5.010,2

State sector 4.112,3 4.249,5 4.178,1 3.873,0

Cooperatives 233,8 231,6 217,0 652,1

Private 602,1 591,3 589,4 485,1

Independent workers 141,6 143,8 147,4 391,5

Source: ONEI, Anuario estadístico de Cuba 2011.

A reading of the data reveals some new features of the national economy regarding employment:

a. The total number of the employed fluctuates around five million people and it should grow significantly in the coming years.

b. The participation of the state sector continues to be decisive in total employment, but it has declined in the past two years.

c. In the non-state sector, the number of the employed decreased as a whole4, but the “cuentrapropista” sector was able to generate 244,000 jobs.

A fact that is relevant to the survival of the cuentapropista sector in the medium and long term is that it has become a significant element of employment for the country, since no other sector with so little capital is able to generate that amount of employment, so it is “socially desirable”. It is also the fastest growing sector in female employment in recent years. All these “objective reasons” give certain guarantee in the medium and long term for the existence of “cuentapropismo”. Today it is a functional sector due to the reforms undertaken in 2007 and consolidated in 2011.

A Fine New Restaurant: Paladar “Dona Eutimia”, Callejon del Chorro, Plaza de la Catedral, opened February 2010; Photo by Arch Ritter

A Fine New Restaurant: Paladar “Dona Eutimia”, Callejon del Chorro, Plaza de la Catedral, opened February 2010; Photo by Arch Ritter

III. Institutionalis m and “cuentapropismo”

Another perspective of this analysis is associated with the institutional protection that has been created to protect the independent sector.

The “modern legal network” directly associated with the expansion of self-employment was initially contained in two special issues of the Official Gazette of the Republic of Cuba published on October 25, 2011 (numbers 11 and 12, dated 1 and 8 October, respectively). They included five legislative decrees, an executive decree, an agreement of the Executive Committee of the Council of Ministers, and fourteen ministerial decisions.4 Probably due to two factors: the contraction of the foreign companies and the loans and services cooperatives.

With regards to Legislative Decree 141 of 1993, the 2011 modernization of the statute introduced obvious advantages, as it:

• Allowed commercial exchanges between “cuentapropistas” and Government entities.

• Authorized hiring a workforce, automatically converting “cuentrapropistas” into micro entrepreneurs.

• Conferred the status of taxpayers and Social Security recipients.

• Authorized access to bank financing.

• Allowed the rental of government or third party premises and assets.

• Authorized the exercise of several trades by the same person.

• Removed the restriction of having to belong to a territory to exercise a trade in it.

• Dispensed with the requirement of being retired or have some employment link to access this form of employment.

• Removed the restriction on the rental of a whole house or apartment, to allow the leasing of rooms by the hour and the use property assigned or repaired by the state in the past decade.

• Allowed the leasing of homes and vehicles to people who have residence abroad or to those living in Cuba, but leaving the country for more than three months, for which they can appoint a representative.

• Increased the capacity to fifty seats in the “paladares”, removed the restriction to employ only family members, and the ban on the sale of food products made with potatoes, seafood and beef.

As a result, a new regulatory environment has been created that exceeds the direct legal network. As part of the reform, as well as other measures authorizing the sale of houses and cars, for example, allows legal improvement to the facilities of the business, and the sale of cars which can improve the “assets” of new businesses.

In addition, the land lease policy and its recent update could facilitate the increase of supplies for those engaged in food services.

A sign that the sector considerations have changed, and that the current government wishes to convey security and transparency, is the submission to the National Assembly in the summer of 2012, of a new tax law that incorporates some additional benefits for independent workers, which include:

• The tax burden of the self employed is reduced between 3% and 7% for the segments with higher and lower income, respectively.

• A tax rate decrease for the use of labor force in the sector of self-employed workers, from 25% to 5% in the term of 5 years. It also maintains this tax exemption for the self-employed, individual farmers and other individuals authorized to hire up to 5 workers.

To these considerations we should add the “ideological and political institutionalization” of the sector, whose best expression is reflected in the words of President Raul Castro:

“The increase in the private sector of the economy, far from being an alleged privatization of social property, as some theorists claim, is destined to become a facilitating factor for the construction of socialism in Cuba, as it will allow the State to focus on raising the efficiency of the basic means of production owned by the people and release the management of nonstrategic activities for the country … we must facilitate the management and abstain from generating stigma or prejudice towards them and demonize them” ….. and later added “This time there will be no return”.

Soon, a new regulation for the operation of cooperatives in the agricultural sector will be released, which will enrich the environment in which the self-employed sector operates, will introduce new competitive challenges and make the economic fabric of the country more complex, generating new production chains.

Certainly, there is still a long way to go. Eventually it will be necessary to formally take the step from “cuentapropismo” to micro, small and medium enterprises. The time has come to consider legislation regulating a negative list (much smaller than the current listing of allowed work) of jobs that cannot be exercised privately. The time has come to incorporate offices and university professionals in jobs directly related to their careers to prevent their loss by emigration or non-use, and/or the waste of human potential unquestionably created in recent years, who have proven to be highly competitive in “other markets “. At some point, it will be necessary to incorporate into the Constitution of the Republic these new realities to begin to delineate a new economic model, but also to begin to draw a new model of development for the country, in which productivity gains and efficiency cannot be expected to only come from the state sector.

1 (*) Professor of the Centro de Estudios de la Economía Cubana, Universidad de la Habana.

(**) Cuentapropista used interchangably with self-employed in translation.

In 1993 it was established who could be self employed: state enterprise workers, retirees, the unemployed who receive subsidies from the State.10 and housewives11, and what activities, especially manual could be included, limiting access to those who could compete with the state.

2 Services that can be offered are limited and are prohibited in some geographic areas, there is no access to bank loans, workers cannot be hired as such (only allowed family work), and a high tax system is applied to independent activities … This regulation determines that the production costs must be assumed by the “cuentapropistas”.

3 In fact, the space gained by some of these “modalities” has ignored certain issues such as the “tourism extra hotels network” always considered inside the state sector but one of the weaker of the government enterprises. Today there are in Havana more than 370 private restaurants and possible more than half of them have appeared since 2011.

Mercado Atesanal, on the Malecon, photo by Arch Ritter

Mercado Atesanal, on the Malecon, photo by Arch Ritter

Bibliography.

Castro R. Periódico Granma, 20-12-10

Gaceta Oficial de la República de Cuba, No. 12, Edic. Extraordinaria, 8-10-12.

Vidal P. y Pérez O. Entre el ajuste fiscal y los cambios estructurales: se extiende el cuentapropismo en Cuba, Espacio Laical No. 4, 2010.

Fuentes, I. Cuentapropismo o Cuentapriapismo: Retos y Consideraciones Sobre Género, Auto-Empleo y Privatización, Cuba in Transition, ASCE, 2000

Ritter A. El régimen impositivo para la microempresa en Cuba, Revista de la CEPAL No. 70, 2000, Naciones Unidas CEPAL, Santiago Chile.

Peter P. “Cuban Entrepreneurs: From Necessary Evil to Strategic Necessity” http://www.american.com/archive/2011/january/cuban-entrepreneurs-from-necessary-evil-to-strategic-necessity

Gonzáles A. “La economía sumergida en Cuba” Revista Investigación Económica, No.2, April-June 1995, INIE.

Suárez L. M. “Cuba: nuevo marco regulatorio del trabajo por cuenta propia” en www.evershedslupicinio.com

Cuenta Propista and Artisan, Photo by Arch Ritter, November 2008

Cuenta Propista and Artisan, Photo by Arch Ritter, November 2008