By Jeff Franks

HAVANA | Wed Mar 20, 2013

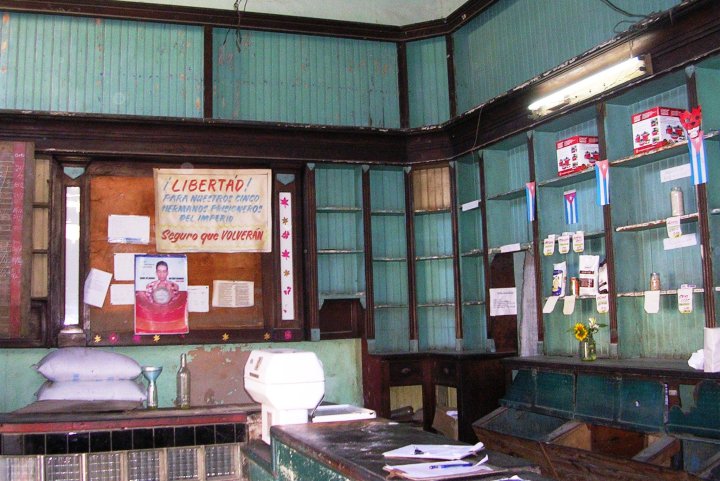

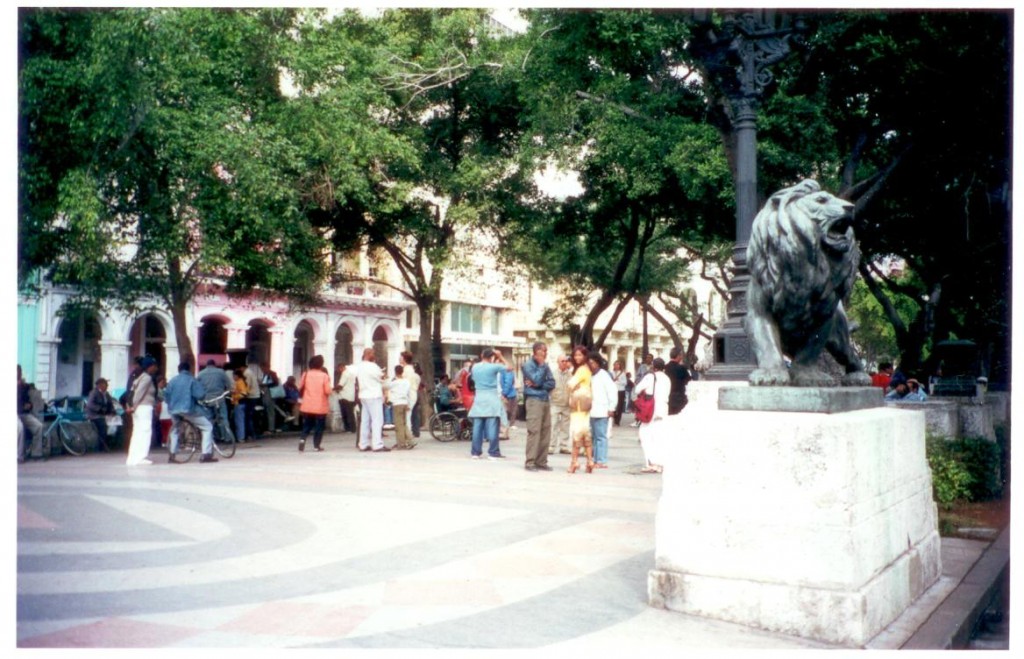

HAVANA (Reuters) – At an informal housing market on Havana’s historic Paseo del Prado, Renaldo Belen puts the hard sell on a prospective buyer under a tree hung with hand-lettered signs advertising homes for sale.

A house near Boyeros, the avenue to the city’s airport, is being offered for the equivalent of $120,000, with all the amenities.

“The house is beautiful; it has four bedrooms, a pool with a bar and a fountain with a lion’s head on top. Look,” says Belen, pointing to photos on the sign, “water comes out of the lion’s mouth.”

Pausing for dramatic effect, Belen, one of the many touts, or “runners” working at the market, delivers what he hopes will be the coup de grace.

“This place needs no work. It is of capitalist construction,” he says, using a now frequently invoked commendation meaning it was built before Cuba’s 1959 revolution and is therefore of superior quality.

Given that “capitalist” has been a dirty word in communist-run Cuba for the last half century, the description perhaps grates on the nerves of Cuban leaders.

But its widespread usage is a sign of the times on the Caribbean island, where President Raul Castro has loosened things up as he tries to modernize the country’s economy in the name of preserving the socialist system put in place by his older brother Fidel Castro.

HOME SALES REPLACE SWAPPING

In November 2011, the government decreed that Cubans could buy and sell homes for the first time since the early days of the revolution, paving the way for a real estate market that has become an exercise in bare-knuckled capitalism. Previously, Cubans could only do swaps – or “permutas,” in Spanish – with their houses.

“For Sale” signs are now a common sight on homes and apartments across the country, more than 100,000 properties are posted for sale on Internet sites and even state television has gotten in on the act, devoting part of a daily show to sales announcements sent in by viewers.

The government last released figures on the market in September 2012 when it said 45,000 dwellings had changed hands in the first eight months of the year, partly through sales, but mostly through “donations.”

Cubans, accustomed to finding ways around heavy-handed government rules and regulations, say many sales are disguised as donations to avoid paying sales fees and taxes.

The new market, despite its apparent vibrancy, is still sorting itself out and still faces hurdles. The main one is that many people are trying to sell and few Cubans, who receive various social benefits but earn on average the equivalent of $19 a month, have the money to buy.

“With the new law, you can sell your house, but there’s no money, nobody to buy. There’s more being offered than there is demand,” said retired economist and math professor Raul Cruz, who has had his apartment in the Vedado district on the market for five months.

Havana was once considered an architectural jewel with an eclectic mix of colonial homes and modern Art Deco construction, but much of the city outside the touristy Old Havana district is in a dilapidated state after decades of neglect and corrosion from humidity and salty sea air.

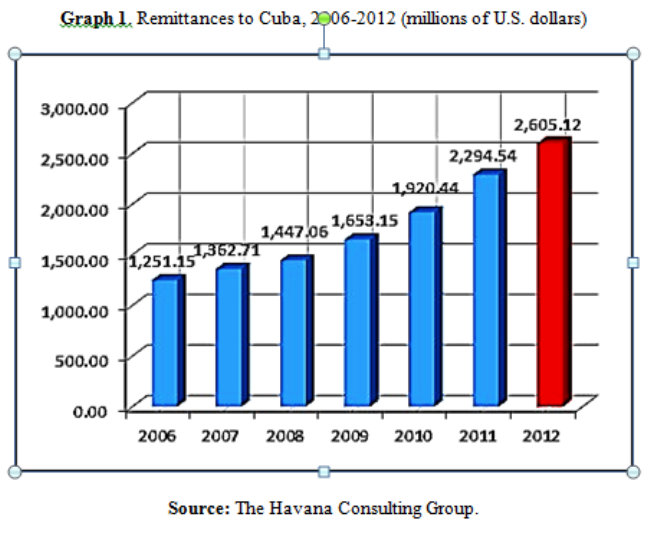

A study by a Miami-based group found that asking prices range from the equivalent of $5,000 to $1 million, with a median price range between $25,000 and $40,000. Cuba has two currencies, the peso and the convertible peso, the latter of which is used in most housing transactions and is pegged one-to-one with the U.S. dollar.

FOREIGN BUYERS?

What has developed is a two-tier market, the runners at Paseo del Prado say, with Cubans mostly buying small places for between $5,000 and $10,000 and foreigners with Cuban connections buying the more expensive properties.

Sixty-year-old graphic designer Pepin, who did not want to give his full name, has been trying for six months to sell his nearly century-old Vedado home, two stories and painted blue, for $130,000.

So far almost everyone taking a look has been a foreigner or a Cuban with family abroad providing the money, he said, and all have tried to bargain for a lower price.

“One Chinese man, for example, offered me 80,000, but I’m not desperate or anything. If they give me what I want, fine. If not, I’ll stay here,” he said, relaxing in a chair on his plant-enshrouded front porch.

By law, the market is open only to Cubans on the island or those living temporarily abroad. But foreigners, including Cubans living in the United States or other countries, are buying properties in the names of Cuban spouses, family members or friends.

Companies with offices abroad have sprung up to cater to foreign buyers, posting photographs and descriptions of properties across the country on the Internet. Attempts to speak with one of them, Point2Cuba, went unanswered.

The reasons foreigners buy are varied, said Emilio Morales, president of the Havana Consulting Group in Miami.

“I have heard of people who are buying homes and turning them into businesses,” he said. “Some are looking for an investment, others doing it for their family (in Cuba).”

The Cuban government has laid the groundwork for allowing foreigners to buy property on the island, but only in resort developments for which approval has been pending for years.

It could inject billions of dollars into the cash-strapped economy by opening the real estate market to all in a new foreign investment law, said Morales.

BARGAIN HUNTING

Information on pricing in the real estate market is sketchy, but the general sense among Cubans is that asking prices began high and have come down somewhat.

Most blame the drop on the supply and demand problems, while others point the finger at another Raul Castro reform – a newly liberalized migration law, which took effect on January 14 and makes it easier for Cubans to go abroad.

“Prices have dropped now because there’s a greater incentive after January 14 to sell and abandon the country. Which is to say that people hurry up and want to sell quickly,” said Roberto Perez, who is trying to sell his two-story home near the sea in Havana ‘s Playa district for $200,000.

The prices depend on the necessity of the seller. “Someone who has a visa (to go to another country) and has a house worth 60,000 may sell it for 30,000,” said Belen, the Paseo del Prado runner.

Selling is being driven by Cubans wanting to cash in on the sole major asset most of them have. One of the quirks of Cuban communism is that while most things are property of the state, the vast majority of the country’s 3.2 million homes are owned by the people living in them.

“This is one of the things that gave longevity to the Revolution. They have something that most people in Latin America don’t have and wish for,” said Miami lawyer Antonio Zamora, a Cuban American who visits the island frequently.

While some sellers want to sell so they can leave, many simply want the money so they can live better in Cuba. Most said they would use part of the money to buy a smaller house, then live off the rest or use it to open a business.

Need and the low economic standards on the island have created some incredible bargains for people accustomed to paying high housing prices in other countries.

One woman, who did not want to give her name or the location of her residence, said she had recently sold the six-bedroom penthouse with a sweeping sea view she shared with several family members for the equivalent of $130,000. The buyer was a European with a Cuban spouse.

“I know it’s going to be worth a lot more in 10 years but everybody in the family wanted the money now. When we were moving out, a man came running up and told me he would give me 50,000 more than whatever the sale price was, but we had already signed the contract,” she said with a sigh.

Zamora, the Miami lawyer, predicted that Cuba would one day be a big market for Cuban Americas retirees.

“This is going to be huge,” he said, noting that Cuba has low crime and health costs, as well as good airport connections to the United States and a well developed money transfer industry for remittances.

“$750 in social security in the U.S. is nothing here in Miami but it can go a long way in Cuba,” he said.

(Additional reporting by Nelson Acosta and Rosa Tania Valdes in Havana and David Adams in Miami; Editing by David Adams and Claudia Parsons)

Arranging “Permutas” in Havana’s Pre-2012 Informal Housing Market, on Paseo del Prado

![r[1]](https://thecubaneconomy.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/r1.jpg)