TED A. HENKEN Y ARCHIBALD R.M. RITTER*

Source: Abajo con el bloqueo en contra de los emprendedores cubanos, tanto en La Habana como en Washington, 14 y medio, Diciembre 13, 2014

Original article here: Abajo con el bloqueo

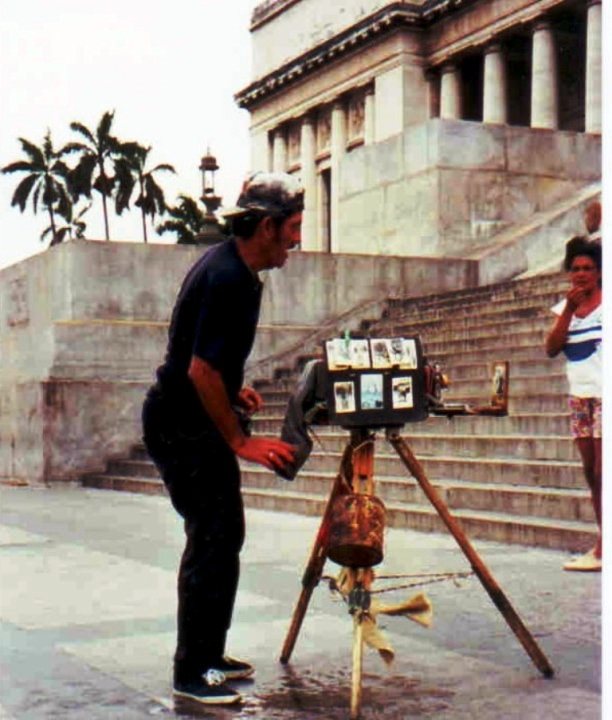

En docenas de entrevistas que hicimos a empresarios cubanos durante los últimos 15 años solíamos oír dos refranes: “El ojo del amo engorda el caballo” y “el que tenga tienda que la atienda, o si no, que la venda”. El primero indica que la calidad de un bien o un servicio mejora (o “engorda”) cuando la persona que lo presta goza de autonomía y obtiene una ganancia económica. El segundo exige que el Gobierno entregue al sector privado las actividades económicas (o “tiendas”) que no ha logrado operar con efectividad, muchas de las cuales ya se practican en la economía sumergida cubana.

En otras palabras, el embargo norteamericano, que ha sido criticado mucho últimamente, no es el “bloqueo” principal que está obstaculizando la revitalización de la economía cubana. Aunque el embargo ha sido condenado constantemente (y creemos correctamente) tanto por el Gobierno cubano como por los editores de The New York Times, en la Isla es mucho más común oír críticas al “auto-bloqueo” (embargo interno) impuesto por el mismo Gobierno cubano en contra del ingenio empresarial de su propio

pueblo.

Entre 1996 y 2006, Fidel Castro dio una gradual marcha atrás a las aperturas económicas que él mismo había implementado durante el llamado Período Especial a principios de los años noventa, demostrando que estaba más preocupado por los riesgos políticos que la iniciativa empresarial popular tendría para su control centralizado que en los beneficios económicos que estos traerían a Cuba. Por eso no estuvo dispuesto a transferir más que una porción simbólica de la “tienda” estatal a los emprendedores privados.

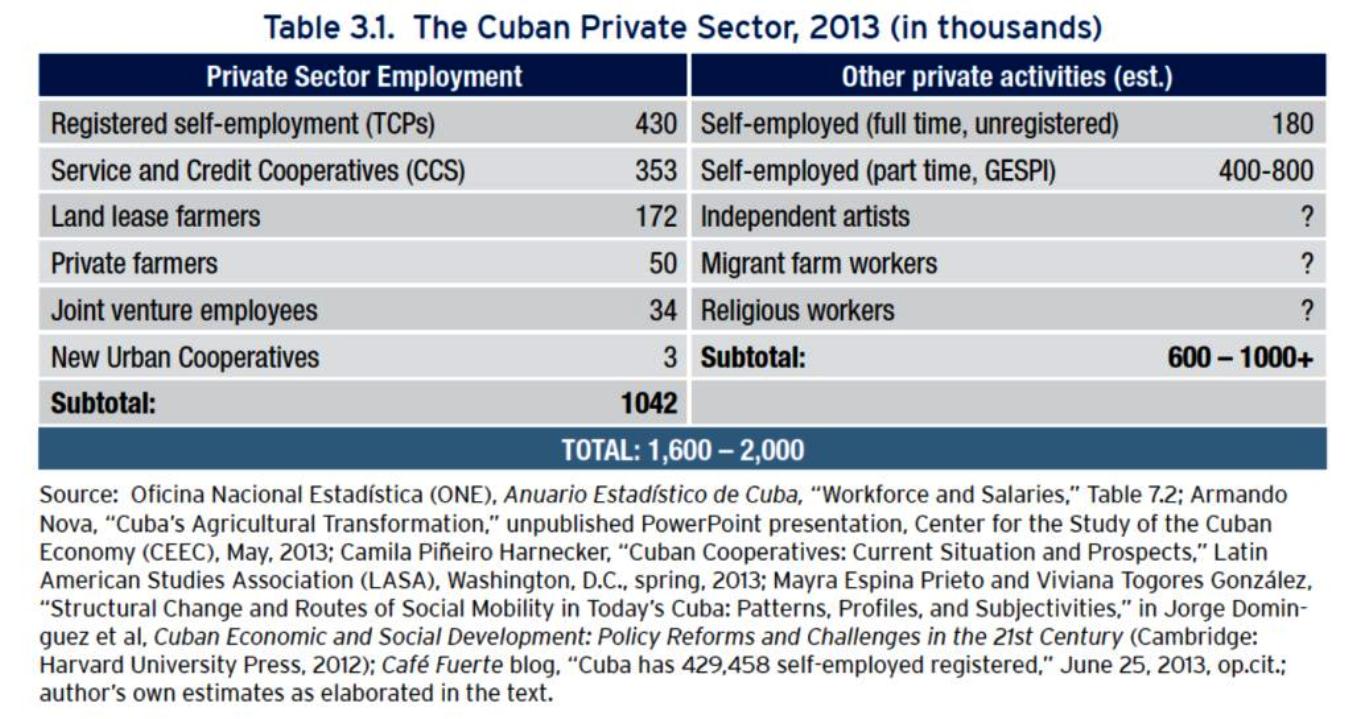

En cambio, durante la presidencia de Raúl Castro, aunque se declara que el objetivo de los cambios económicos sigue siendo “preservar y perfeccionar el socialismo,” él ha empezado a hacerle caso a la sabiduría popular de los refranes citados arriba reduciendo el tamaño de la “tienda” estatal al transferir la producción de últiples bienes y servicios a las cooperativas y pequeñas empresas privadas. De hecho, el número de los trabajadores por cuenta propia ha aumentado de menos de 150.000 en 2010 a casi medio millón hoy.

No obstante, hace falta hacer mucho más para que los empresarios cubanos puedan contribuir plenamente al crecimiento económico. Por ejemplo, el 70% de los nuevos trabajadores por cuenta propia vienen de las filas de los “desempleados”, una cifra que indica que simplemente legalizaron sus empresas informales ya existentes, por lo que no están creando empleos que absorban a los 1,8 millones trabajadores del sector estatal despedidos por el Gobierno.

Solamente un 7% de los trabajadores por cuenta propia son universitarios y la mayoría trabajan en actividades de bajo nivel porque casi todos los empleos por cuenta propia profesionales están prohibidos. Esta prohibición resulta ser un “bloqueo” bastante eficaz que obstaculiza el uso productivo de la fuerza de trabajo cubano altamente calificada.

Para “acabar con el bloqueo” contra los empresarios cubanos y así facilitar el surgimiento de un sector privado de empresas cooperativas y de pequeña y mediana escala hay que emprender reformas más profundas y audaces. Entre estas, una apertura de las profesiones a la empresa privada; la implementación de mercados mayoristas y crédito asequibles; acabar con el fuertemente custodiado monopolio de estado sobre las importaciones, las exportaciones y la inversión; permitiendo el establecimiento de empresas de venta al detalle; y relajar la presión fiscal sobre la pequeña empresa, que actualmente discrimina a las empresas nacionales a favor de las extranjeras.

¿Tiene Raúl Castro la voluntad política para profundizar sus reformas?

La prohibición de las actividades que el Gobierno prefiere monopolizar le permite ejercer un control sobre las ciudadanos cubanos e imponer un orden aparente sobre la sociedad. Sin embargo, esto se alcanza al precio de empujar toda la actividad económica prohibida (y toda ganancia impositiva) nuevamente al mercado negro donde se desarrollaba antes del 2010.

Por el otro lado, la legalización y regulación de las muchas actividades creadas y puestas a prueba en el mercado por el creativo sector empresarial cubano crearía más puestos de trabajo, una mayor calidad y variedad de bienes y servicios a precios más bajos, al tiempo que aumenta los ingresos fiscales. Pero estos beneficios vendrían a costa de permitir una mayor autonomía económica, la concentración de riqueza y propiedad en manos privadas y abrir la competencia contra los monopolios de estado por mucho tiempo protegidos.

La viabilidad de estas reformas depende también de cambios en la política norteamericana hacia Cuba y de la política cubana hacia su diáspora, la cual ya juega un papel importante en la economía cubana como proveedores de capital inicial a través de los miles de millones de dólares que mandan cada año en remesas. Otro fenómeno cada vez más importante es el amplio coro de voces en Estados Unidos, incluyendo a muchos prominentes miembros de la comunidad cubana-americana, que reclaman una nueva política norteamericana hacia Cuba.

Al reclamar reformas económicas más profundas dentro de Cuba, también creemos que unos cambios calibrados en la política norteamericana podrían estimular la apertura del mercado al permitir más apoyo material y técnico a los nuevos empresarios cubanos. Este acercamiento responsable al cada vez más robusto sector de las pequeñas empresas independientes de Cuba, puede y de hecho debe ser permitido, para estimular la expansión de las reformas económicas de Cuba y por tanto potenciar la autonomía económica del pueblo cubano.

Si el Gobierno cubano insiste en mantener un embargo a su propio pueblo, no debemos nosotros ayudarlo con nuestro propio embargo externo. Por el contrario, deberíamos hacer lo opuesto trabajando directamente con los florecientes empresarios de Cuba.

*Ted A. Henken es Jefe del Departamento de Sociología y Antropología de Baruch College, City University of New York. Archibald R.M. Ritter es Profesor de Investigación Distinguido Emérito de Economía y Asuntos Internacionales de Carleton University, Ottawa, Canadá. Su nuevo libro, Entrepreneurial Cuba: The Changing Policy Landscape, se publica en enero de 2015.