Son of a Cuban émigré, John Paul Rathbone asks what Fidel’s death means for the republic’s people

John Paul Rathbone, Financial Times, December 2, 2016

Original Article: Joy and Sadness for Castro’s Cuba

It has been many years since my family celebrated the usual exile toast which tacitly imagined Fidel Castro’s death — “To next Christmas in Havana!”

My mother’s family left Havana in the autumn of 1960 — 18 months after Castro came to power — expecting to return soon. But as the years passed, the toast I heard as a child growing up in London grew heavier with irony. By the end of the 20th century, it was repeated only because the repetition was comic. Then, last Friday at 10:29pm, Castro really did die. His younger brother, President Raúl Castro, made the announcement on national television.

I learnt the news on Saturday morning, in New York. My phone was lit up with texts and emails. In Miami, the night before, my niece had rushed out of her apartment in the Cuban district near Calle 8 to join the euphoric crowd. In Madrid, a cousin celebrated in a Cuban dive bar with a hip audience and politics far to the left of his own — and those of the owner, a black Cuban in his early 60s who served the crowd cocktails but kept his satisfaction to himself. From Havana, the mother of a friend left a strange message on his answering machine: “Fidel is dead”, and then a long silence before she hung up.

“DEAD” was the bald Miami Herald headline on its special edition. There was little more to say. Cuba has been “post-Fidel” since he retired from public office in 2006 because of ill-health, formally handing over power to Raúl in 2008. One friend who heard the news on Friday night simply went back to sleep. The revelry outside Miami’s famous Versailles restaurant soon rang hollow. It was a moment instead for grief, that churning of old emotions whenever a major figure in your life dies.

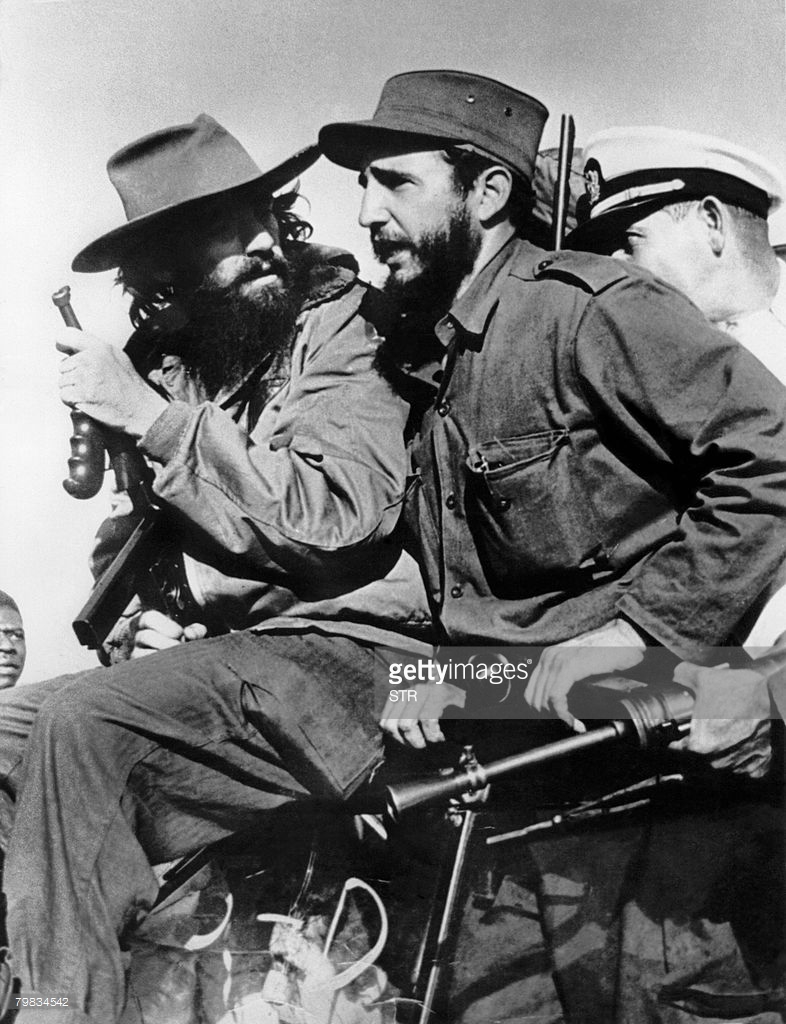

I called my mother in London. Although she left Cuba several years before the revolution for reasons that had nothing to do with politics, she often returned and had cheered Castro’s jubilant rebels and thrown flowers in their path when they had marched into Havana 57 years ago, the dictator Fulgencio Batista vanquished. She claims to have hugged Camilo Cienfuegos, the most-loved rebel leader, that day. But then Castro nationalised my grandfather’s store, and soon her parents and siblings and their children left too. “So many memories,” she told me.

Camilo Cienfuegos and Fidel Castro, January 1 1958

I returned to Miami on Sunday evening. Driving home from the airport, I asked my Uber driver, a 26-year-old who left Havana four years ago, about his weekend. He was dismissive. “I understand the celebration. It’s not of a person’s death. It is of the end of someone who has caused so many people so much pain. But nothing really has changed. I stayed at home.”

Charismatic defiance

There is still, though, the public weighing of Castro’s life, the lengthy consideration of this versus that. Hero or villain?

First, we need a necessary correction of perceptions. Even Cubans who dislike him sometimes take a strange pride in Castro. “Fidel embodied the best and worst of us,” wrote Achy Obejas, a Cuban-American novelist, in a New York Times column this week. “We hated his ambitions and loved that he had them. Hang out with a bunch of Cubans, and the minute someone gets imperious, someone else will call her out for the ‘little Fidel’ in her.” It’s in every Cuban, really.

Castro (left) is shown in file photo dated May 1963 holding the hand of Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev during a four-week official visit to Moscow. Castro resigned on Feb. 19, 2008 as president and commander in chief of Cuba in a message published in the online version of the official daily Granma.

Castro was epic, especially from afar. He seemed to rule forever. He was the Quixote whose defiance of the Yankee monster warmed the cockles of the hearts of the red, the young and the poor. His charisma was inarguable.

There were also the achievements, especially Cuba’s lauded education and health systems, and the fight against South African apartheid. His longevity — outlasting 11 US presidents — won him the respect of Latin American leaders. European, African and Asian politicians played court too.

Up close, however, his portrait becomes like the picture of Dorian Gray. There were the summary executions in the early days of the revolution; the stifling ideology that followed; the neighbourhood snooping; and the official discourse with its sledgehammer words like “conflict” and “struggle” but never “prosperity”, “reconciliation” or “harmony”. There were, and still are, the desperate escapes across the Florida Straits in makeshift rafts, the stultifying economy, the drain of the talented and the young seeking a life for themselves as exiles, and the fact that while Cuba’s island population is 11m, another 2m live abroad.

More than anything, though, there has been the terrible breaking apart of families — and Cuba, under all the politics, is a family affair. I think of this analogy. At his height, Castro was the father of the nation — the man who shaped everyone’s lives. Yet he was also an abusive father. On Tuesday night, as I watched the state funeral in Revolution Square on the television, I noticed that Raúl never used the word “brother” during his tribute speech. With Castro, it was politics all the way.

FILE – In this April 19, 2016 file photo, Fidel Castro attends the last day of the 7th Cuban Communist Party Congress in Havana, Cuba. Fidel Castro formally stepped down in 2008 after suffering gastrointestinal ailments and public appearances have been increasingly unusual in recent years. Cuban President Raul Castro has announced the death of his brother Fidel Castro at age 90 on Cuban state media on Friday, Nov. 25, 2016. (Ismael Francisco/Cubadebate via AP, File)

Cuba waits

Castro’s death at the age of 90 is, of course, one of the most unsurprising news events ever. The obituaries were written long ago. Nothing happening this past week on the island has been improvised either, even if most Cubans had probably not expected to trudge through nine days of state-mandated mourning, with alcohol sales banned.

On Wednesday, after tributes from foreign dignitaries the night before, Castro’s ashes were driven off in a cortege on an 870km tour across the island. On Sunday, his ashes will be interred at the Santa Ifigenia cemetery in Santiago, in a tomb next to José Martí’s: Castro has thereby sought to appropriate the legacy of the poet and man of letters who is Cuba’s most famous independence hero.

Castro’s own legacy will be disputed for years. For every argument in its favour, there is a riposte. What is inarguable is that the island is physically crumbling, and the economy in desperate need of investment and funding. Socialist Venezuela, Cuba’s closest ally, faces an economic crisis. Soon Caracas may no longer provide Havana with the aid and subsidised oil it needs.

When I last visited Cuba in July, there were blackouts. A euphoria I sensed in February, an expectancy of change triggered by President Barack Obama’s historic visit and the prospect of subsequent US rapprochement, had faded. The significant but small economic reforms launched by Raúl have stalled. The generals still control the most lucrative sections of the Cuban economy. When Raúl steps down as president in 2018, as he has promised, the system will probably be much the same as now. But perhaps it will be otherwise.

Cubans also face the prospect of Donald Trump. The US president-elect has threatened to reverse Mr Obama’s detente. “If Cuba is unwilling to make a better deal for the Cuban people, the Cuban/American people and the US as a whole, I will terminate the deal,” Mr Trump tweeted this week.

It is hard to see the logic of how a return to a US policy that failed when Castro was alive will succeed now that he is dead. Squeezing Cuba again will more likely prompt the turtle to shrink back into its shell. But does Mr Trump really want that for the island nation anyway, even if many Cuban American Republicans do?

It is only a straw in the wind, but Maria Romeu, who concierges yacht charters to Cuba from Florida, continues to take lots of bookings from her largely Republican clients. On a recent Havana trip, the 58-year old Cuban American took four wealthy Trump voters on a city tour where they imagined where the Trump Tower might be built. “They were quite elated and the possibility of not going to Cuba next April did not cross their mind,” says Ms Romeu, who adds that the bookings for next summer are intact. “I’m taking their lead.”

It is ironic that the death of one of the 20th century’s most charismatic nationalists, the narcissistic father figure Fidel, coincides with the rise in the US of another charismatic nationalist, Mr Trump. For some, it is a worrying symmetry; a populist playbook seen before.

“I don’t care if Castro is alive or dead. That was already a done deal for me,” a family friend wrote on Facebook. “Instead I care about those who still think he was great. That is bothersome, and dangerous, because it is a trap. A trap that can ruin lives — like those who think Donald Trump is great, [believe his promises] and yet you see the train wreck coming.”

I left for Cuba on Friday, with no great expectations, but wanting to witness Castro’s passing. His death, it seems to me, truly marks the end of the 20th century and also of certain attitudes that already seemed old-fashioned and outdated many years ago.

John Paul Rathbone