Financial Times, June 21, 2013 5:02 pm

By John Arlidge

The country is finally allowing its people to buy and sell homes but property lawyers and agents are still illegal.

It’s only 9am but it’s already 33C on the Malecón, Havana’s corniche, and my brain feels like a conch fritter. I’ve come to meet a man who we will call Rafael – because that’s his name. But that’s the only part of his name he is prepared to reveal. Rafael is an estate agent but he does not want anyone to know it. “Being an estate agent is illegal here,” he says.

If we do agree a price, Rafael will advise me not to buy the penthouse in the normal way. Instead, to avoid tax, I should pay him a nominal amount locally, say 20 per cent, and “deposit the rest in an account in Spain, please”. I must not talk about the true price because, under new laws, anyone caught lying about the price of property goes to prison. Also, I must not reveal the name of the lawyer who does the paperwork because working as a private property lawyer is illegal.

Undercover estate agents? A legal system that is illegal? Jail for lying about house prices – which everyone the world over does? Welcome to the oddest property market in the world. Welcome to Cuba.

Half a century after Fidel Castro’s government expropriated all private property, the sunshine socialist state is up for sale – in part. Raúl Castro, who took over as president from his ailing brother in 2008, has introduced new laws that allow Cubans to buy and sell homes. Billions of dollars in property assets that have been frozen in place and time, unvalued or undervalued, are now up for grabs.

Raúl Castro’s move is the latest – and boldest – step in a slow economic liberalisation programme designed to generate economic growth. Cuba desperately needs new sources of revenue. It is only kept afloat thanks to cheap oil, and other subsidies worth $5bn a year from its ideological ally, Venezuela. The subsidy deal was agreed by Fidel Castro and former Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez, who died in March. If Venezuela’s new president, Nicolás Maduro, renegotiates the agreement – and many analysts say that, with Venezuela’s economy slumping, he has no choice – Cuba will grind to a halt.

After half a century in which they could only swap houses in a creaky, bureaucratic and often corrupt state-run process known as permuta (exchange), which involved finding two properties of roughly equal value and then getting state approval to transfer the title, Cubans are relishing their new-found economic freedomFirst-in-a-lifetime buyer Guillermo Rey stands next to the scruffy portico of a four-bedroom, three-bathroom house in Vedado, Havana’s most high-end, fashionable district. The price, says the owner Rosa Marin, is 350,000 CUC, or convertible pesos, Cuba’s hard currency, which is roughly equivalent in value to the US dollar. She is selling because she wants to move into a smaller property “and buy my daughter a car, a good one, a Lada”.

It is a scene repeated all over Havana. The market is growing so fast that queues form outside the tumbledown offices of Cubisima, a Havana-based property sales website. “Every day we get more people looking to sell and more people looking to buy,” Mayelin Aguilar tells me as she keys the latest listings into her bulky Russian-built desktop computer – so old it still runs Windows 95.

The tree-lined Prado is polka-dotted with estate agents, their listings written in longhand in school exercise books. Their commission? A whopping 5 per cent – if, that is, the buyer pays up. With estate agency not on the approved list of private businesses Cubans can now set up, buyers know agents have no recourse to law, so many simply refuse to pay. “I’m lucky if I get commission for one deal in five,” says one agent.

Some 45,000 homes were sold in 2012, according to Cuba’s National Statistics Office. Observers say informal deals take that number to almost 100,000. Prices range from $10,000 for a small, run-down flat in Old Havana to $500,000 for villas in sought-after districts, such as Siboney and Miramar, and more than $2m for penthouses in modern blocks. The average price last year was just $16,000. The Cuban on the calle is still desperately poor.

This being Cuba, the conditions surrounding home sales are complicated and, occasionally, bonkers. The law says that only Cubans and permanent residents can buy and sell property and they must limit themselves to one main residence and, if they have the money, one holiday home. Raúl Castro does not want Cubans to become property barons.

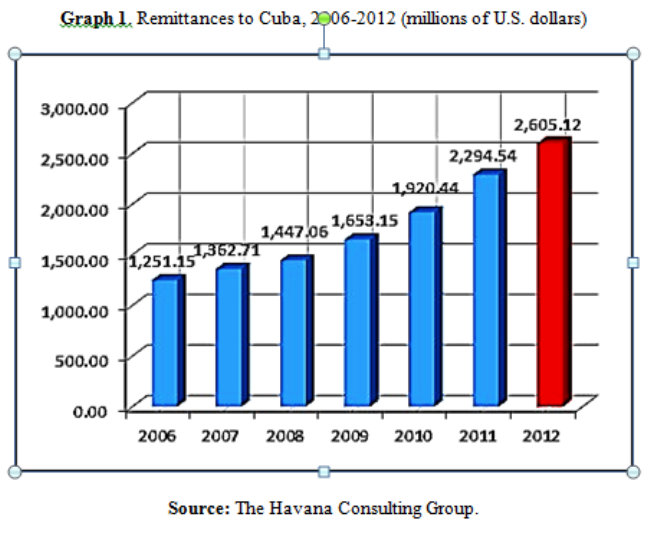

Nor does he want to encourage armies of foreign investors, especially the many arch-critics of the regime, to descend on Havana and buy it up, block by block. But, thanks to an early flirtation with capitalism 20 years ago, there are a few apartment buildings in Havana where foreigners can buy. The best are in the Atlantic Building, a 25-storey tower on the Malecón, where Rafael shows me the penthouse he says is worth $2.5m. Few want to say so publicly but some are being snapped up by Miami-based Cubans, via local relatives, making it difficult to divine whether the émigré Cuban or the relative is the real buyer. President Barack Obama recently relaxed the restrictions on foreign remittances from Cubans living in the US. Up to $5bn a year now flows into Havana and much of it ends up in bricks and mortar.

Other overseas investors get around the restrictions by giving money to a Cuban friend, or more often, girlfriend, to buy a property – although, when the deal is completed, some swiftly discover that their girlfriend is no longer their girlfriend. “I took a risk and it failed,” sighs one Dutch-born investor, whose $400,000 “home” in the fashionable Kholy western suburbs is now home to his former girlfriend and her extended family who cannot believe their luck – and his naivety.

Tax is troublesome, too. Both sellers and buyers must pay 4 per cent but most disguise the value of deals to reduce the liability. Raúl Castro’s dream of generating much-needed tax revenue from home sales is, so far, a forlorn hope.

But he might have an ace up his linen guayabera shirt – or, rather, 130km down the cracked highway from Havana in Varadero. It is Cuba’s “touristic zone”, a ghetto of white sand and whiter westerners, who sip mojitos and snap up Che Guevara T-shirts without bothering to wonder what Che would make of them splurging their Yankee dollars on a swanky beach holiday.

“This is where the £1.5m villas will be. And, over here, right next to an 18-hole golf course, is where the country club will be,” says Andrew Macdonald, striding across the scrub in canary yellow shorts. The Scots-born entrepreneur runs Esencia, an Anglo-Cuban firm, that wants to build Cuba’s first new golf course since the revolution, with 800 homes available for foreigners to buy.

He has signed up some big names to build the $350m development at Carbonera, near Varadero. Sir Terence Conran will design the homes. Adrian Zecha, founder of Aman resorts, is in charge of the country-club-cum-hotel and spa. Golf champion Tony Jacklin will help design the golf course. “Cuba is the top emerging tourism market in the Caribbean by a mile, and it’s in the top five emerging markets globally,” Macdonald says. “It’s a long slog getting stuff done but the potential is huge.”

“Slog” hardly does justice to the tortuous process he has had to undergo to get this far, and which has cost him $3m on feasibility studies. He began negotiations in 2006 and each year the government has said it will approve the venture. But each year then becomes next year. Manuel Marrero, Cuba’s minister of tourism, says the deal has finally been approved in cabinet but Macdonald still does not have the formal sign-off he craves.

Ministers may not like it but they know the only way to balance the books is to encourage the local market

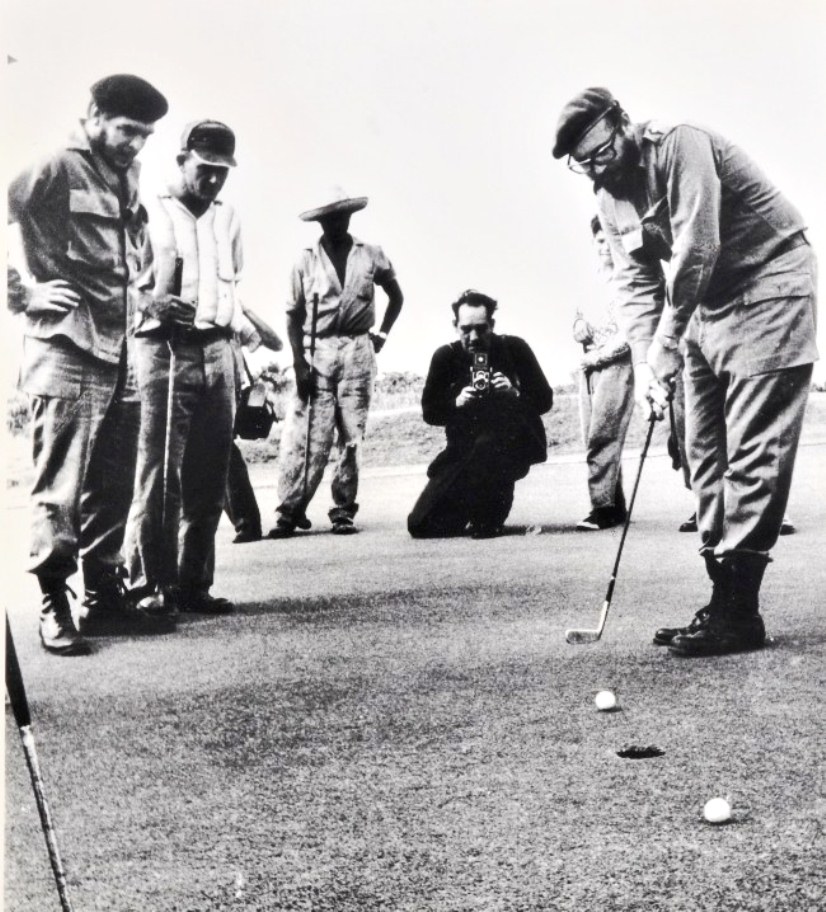

If and when Macdonald, 47, does get the formal go-ahead, it will mark the end of Cuba’s bunker mentality when it comes to golf. Fidel Castro declared golf “incompatible with the glorious revolution” and ordered Cuba’s courses to be put to less “bourgeois” use. Today, one of them lies abandoned just outside Havana; another is a military special forces training ground; and a third forms the rolling lawns of a city’s arts school.

Macdonald wants to build 150 colonial-style oceanfront villas and 670 apartments. Prices for the apartments will start from $2,700 per sq metre and range from 75-140 sq metres. The villas will cost $3,750 per sq metre and range from 350-600 sq metres. Six-hundred investors have registered an interest, Macdonald says. Buyers will have what passes for freehold title under Cuba’s nascent property laws, and will be able to rent out their property.

Artist’s Depiction of Esencia Housing Project Proposal

Cuba has retained the original Spanish, pre-revolutionary land registry and Macdonald says it shows that no overseas parties have a claim on the land at Carbonera. Tens of thousands of exiled Cubans, who left the country after the revolution, still claim rights over properties. On a bluff just along the coast from Carbonera stands the DuPont villa, the former vacation home of the wealthy US chemicals family. It is now a government-run guest house.

Investing in Cuba is only for the most steely-nerved. Not only is there the vexed question of potential claims on properties from exiled Cubans, the Cuban government has a long, ignominious history of first encouraging and then choking off economic liberalisation. It relaxed restrictions on home sales 15 years ago, only to reverse the policy a few years later.

This time, however, observers say Raúl Castro, who is more pragmatic and less ideological than his older brother, is unlikely to do a U-turn. One western business leader, who has set up a financial services consultancy in Havana, says: “Cuba is bankrupt. Ministers may not like it but they know the only way to balance the books is to encourage the local market and to allow overseas investors to build homes and golf courses and maybe eventually buy villas in Havana.”

That would be good news for Rafael. The more the market expands, the sooner he hopes the government will legalise his profession. “That way,” he smiles, “the next time you come into Cuba, I can tell you my name.”

![r[1]](https://thecubaneconomy.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/r1.jpg)