January 13, 2015 Policy Beat

Original here: US :Cuba Immigration policy

By Marc R. Rosenblum and Faye Hipsman

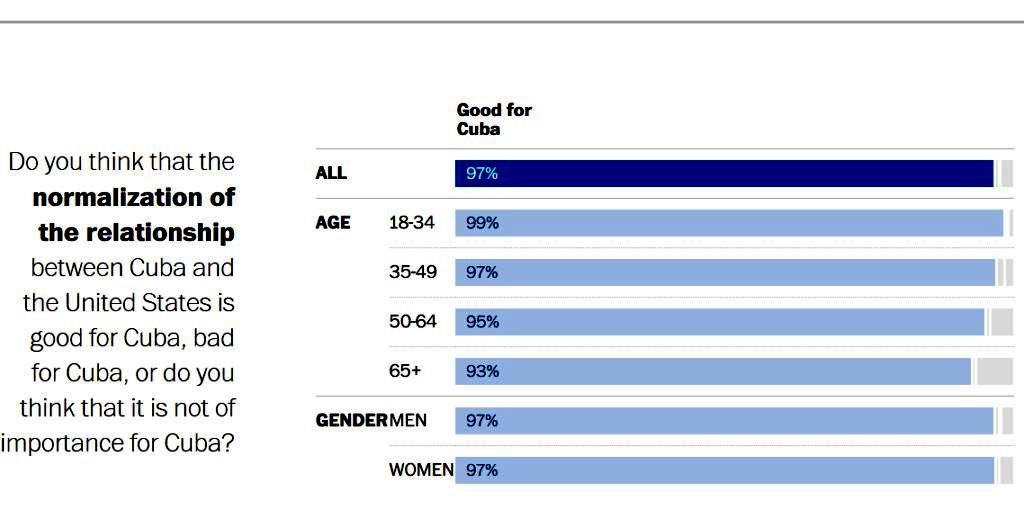

The historic December 2014 agreement by President Barack Obama and Cuban President Raúl Castro to normalize relations between the United States and Cuba may herald revisions to immigration policy and create changes that affect the future migration of Cubans to the United States. The decision to re-establish diplomatic ties with the island nation, severed more than half a century ago after the Cuban revolution in which Fidel Castro seized power and established a socialist government, will prompt a series of sweeping changes. The United States will reopen an embassy in Havana; greatly relax restrictions on trade, travel, remittances, and financial transactions; and re-evaluate Cuba’s decades-old designation as a state sponsor of terrorism.

The two countries have also agreed to greater cooperation on areas such as counter-narcotics, environmental protection, and human trafficking. Despite the long estrangement, the United States and Cuba have cooperated on migration issues for decades and have agreed to do so in the future. While the United States has stated that its immigration policy toward Cuba—which affords Cubans uniquely favorable treatment—will for now remain unaffected, improved overall relations will make today’s immigration arrangements difficult to sustain.

Currently, Cubans who arrive in the United States, even without proper authorization, are granted entry and benefit from a fast-track process that allows them legal permanent resident (LPR) status after one year in the country. This unique policy, based on a presumption that all Cuban emigrants are political refugees in need of protection, may need revision now that a détente is at hand. As the two countries improve relations and open their travel channels, policies that automatically welcome Cubans—including illegal entrants and visa overstayers—and accelerate their access to a green card may need to be revisited.

A Cold War mentality has dominated the U.S. approach to its small southern neighbor since the Cuban revolution in 1959, focused chiefly on isolating the country through economic sanctions in opposition to Cuba’s socialist model. The United States has also cited major human-rights concerns for maintaining a trade embargo and implementing tough travel and financial restrictions. In his December announcement, President Obama called this approach outdated, saying that five decades of U.S. isolation of Cuba had failed to achieve the objectives of promoting democracy, growth, and stability there.

The U.S.-Cuba Migration Relationship

Fraught political relations between the two countries, combined with their geographic proximity, have afforded Cuba a place that is sui generis in U.S. immigration law and policy. On the one hand, the United States has offered generous refuge to Cubans fleeing communism; on the other, it has discouraged illegal and dangerous boat migration from Cuba, which has occurred in large waves several times in recent decades.

The population of Cuban immigrants in the United States surged after the revolution, rising from under 71,000 in 1950 to 163,000 by 1960. In the immediate aftermath of the overthrow of the Fulgencio Batista regime by Castro-led revolutionaries, many wealthy Cubans and other opponents of the Marxist forces fled, particularly as Castro began nationalizing private property. Under Operation Pedro Pan, organized by religious organizations in Miami with the support of the U.S. government, approximately 14,000 unaccompanied children whose parents opposed the Castro regime were flown to the United States between 1960 and 1962. In September 1965, the first Cuban “boatlift” began when the Cuban government announced that people were free to leave for the United States from the port of Camarioca. When thousands sought to take advantage of the opportunity, many in unsafe vessels, the United States and Cuba reached an agreement to instead allow Cubans to fly to Miami on chartered “Freedom Flights;” about 300,000 Cubans arrived this way between 1965 and 1973.

The cornerstone of U.S. immigration policy toward Cuba is the 1966 Cuban Adjustment Act (CAA), which Congress passed to accommodate these flows after amendments to the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) in 1965 limited the number of Cubans (and other Western Hemisphere immigrants) who could receive visas. Under CAA, all Cubans who arrive in the United States are presumed to be political refugees, and are eligible to become legal permanent residents (LPRs or green card holders) after one year, assuming they are otherwise admissible. Two decades later, when Congress passed the 1980 Refugee Act establishing the current U.S. refugee and asylum system, the CAA provisions were left in place. Under the 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act, the CAA will sunset once Cuba becomes a democracy.

Following termination of the Freedom Flight program, most Cubans seeking to enter the United States have traveled by sea, and the attempts of hundreds of thousands of Cubans to make the perilous journey across the Straits of Florida have played a large role in shaping U.S. immigration policy toward Cuba. In 1980, maritime departures surged dramatically during the Mariel boatlift, when Fidel Castro opened the Cuban port of Mariel, allowing anyone to depart the country—including several thousand criminals and mentally disabled individuals. In the six months the port remained open, 125,000 Cubans (along with 25,000 Haitians who joined the flotilla) arrived in South Florida. Boat migration again surged in the mid-1990s. U.S. Coast Guard interdictions of Cubans jumped from 2,882 in fiscal year (FY) 1993 to 38,560 in FY 1994.

The 1994 surge prompted a pair of far-reaching migration agreements between Cuba and the United States in 1994 and 1995. Before then, Cuban migrants interdicted at sea by the Coast Guard were admitted to the United States, a practice widely criticized for encouraging more Cubans to attempt the risky journey. Under the 1994 agreement, Cuba agreed to discourage boat departures, while the United States agreed to grant admission to at least 20,000 Cuban nationals annually and to place intercepted Cubans in safe havens to be considered for asylum. Under the 1995 agreement, the United States granted parole status to the roughly 30,000 Cubans awaiting an asylum determination, and changed its policy to returning future migrants interdicted at sea directly to Cuba. Cubans who expressed a fear of persecution upon return and were determined to meet the refugee definition would no longer be eligible for asylum in the United States, but resettled in third countries.

Combined with the CAA, the 1994 and 1995 migration accords set forth the current “wet-foot, dry-foot” policy. Cubans intercepted at sea are returned to Cuba, where the government has pledged not to retaliate against them. Those who successfully reach the United States are permitted to stay, and become eligible to apply for a green card after a year.

Furthermore, to meet the 20,000 admission floor negotiated in the 1994 accords, the United States instituted the Special Cuban Migration Lottery. The lottery, held in 1994, 1996, and 1998, allowed Cuban nationals between the ages of 18 and 55 to register for admission to the United States, provided they possess two of the three following characteristics: a secondary school or higher education, three years of work experience, or a relative residing in the Unites States. Up to 20,000 lottery winners per year (depending on the number of Cubans admitted through regular visa processing) are granted parole status, and may bring their spouse and children. With 541,000 Cubans entering the lottery between 1994 and 1998, Cubans selected in 1998 continue to be paroled into the United States today.

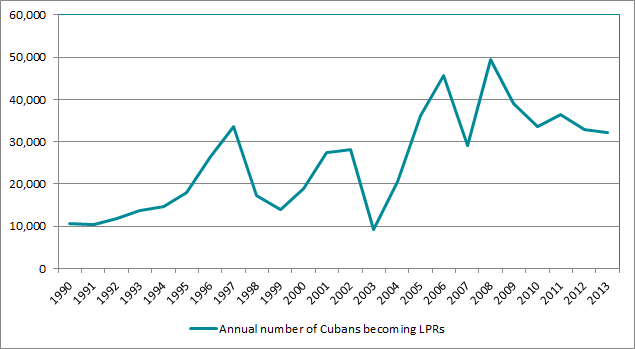

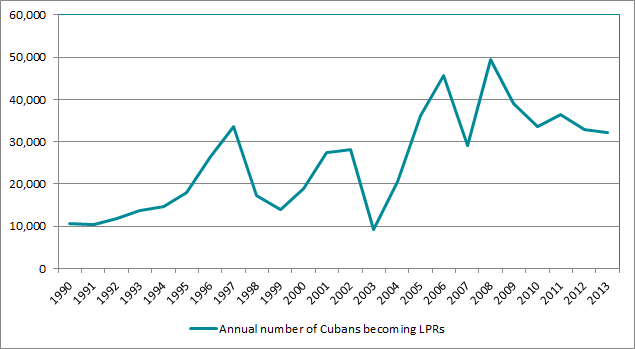

As a result of these policies, and in spite of the hostile relations between the two countries, Cubans represent one of the ten largest foreign-born groups in the United States, with an estimated 1.1 million immigrants (2.7 percent of the foreign-born population). Collectively, Cuban immigrants and their U.S.-born descendants represented a diaspora of 2.1 million in 2011. Cuba also ranks highly as a sending country for new green-card holders, which have numbered in the 30,000s in each of the past five years (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Annual Number of Cubans Gaining LPR Status, 1990-2013

Source: Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Office of Immigration Statistics, Yearbook of Immigration Statistics 2000-2013 (Washington, DC: DHS, Office of Immigration Statistics, various years), www.dhs.gov/yearbook-immigration-statistics.

Source: Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Office of Immigration Statistics, Yearbook of Immigration Statistics 2000-2013 (Washington, DC: DHS, Office of Immigration Statistics, various years), www.dhs.gov/yearbook-immigration-statistics.

Loosening Travel Restrictions

Travel between Cuba and the United States has been tightly controlled for much of the last half-century. Americans are only permitted to travel to Cuba for certain authorized purposes, such as educational, religious, humanitarian, or journalism trips. In 2013, Cuba changed a long-standing policy requiring its citizens to obtain an exit permit and letter of invitation from a country abroad in order to travel internationally, even temporarily. Most Cuban nationals now only need a valid passport and visa to depart, although certain skilled workers are excluded from the loosened rules. In response to Cuba’s policy change, the State Department extended the validity of B-2 tourist visas issued to Cubans from six months (single-entry) to five years with multiple entries permitted. Between 2012 and 2013, nonimmigrant visas issued to Cubans jumped 82 percent, from 20,200 to 36,787.

Future Implications

Cuba receives unique treatment under U.S. immigration law. No other nationality is given a blanket right to green-card eligibility, no other country has a floor below which visas may not fall, and no other group of immigrants is guaranteed admission to the United States if they appear at or between ports of entry. In effect, Cuban nationals are exempt from deportation and immigration enforcement policies affecting all other noncitizens. Furthermore, because Cuban arrivals are treated similarly to refugees, many are eligible for federal assistance and means-tested benefits from which most noncitizens are barred.

As the Obama administration and Cuba take steps to normalize their relations, trade and travel between the two countries is only expected to increase. While Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson has stated that current immigration policy and law concerning Cuba will remain “for the time being,” expanded travel and trade raise questions about the viability of the wet-foot, dry-foot policy and the Cuban Adjustment Act: As visa issuance to Cuban nationals increases, will a growing number of Cubans overstay their visas in order to obtain green cards? A policy that rewards those who violate the terms of their visas is sure to invite questions of fairness. How will the U.S. policy of automatically treating Cubans who reach the United States as refugees affect bilateral relations once diplomatic ties are restored?

Indeed, the Coast Guard has already reported a spike in interdictions of Cubans at sea since the announcement, with 500 interdictions in December—three times the typical amount. The Coast Guard attributes the spike to fear among Cubans that the United States could soon repeal the wet-foot, dry-foot policy.

However, while improved relations may create a pressing need for normalized immigration policies toward Cuba, both Cuba and immigration are highly polarized political issues. Permanently changing these laws will ultimately require approval by the U.S. Congress, and faces a steep uphill climb.

Playas deEste, August 1994. Did They Make it?