CNBC.com

Ted Henken, November 14, 2016

One example of freer markets in Cuba isthe Paladar La Cocina de Lilliam (Lilliam’s Kitchen), a home-based restaurant garden where President Jimmy Carter ate on his first visit to Cuba in 2002. Photo: Ted Henken

One example of freer markets in Cuba isthe Paladar La Cocina de Lilliam (Lilliam’s Kitchen), a home-based restaurant garden where President Jimmy Carter ate on his first visit to Cuba in 2002. Photo: Ted Henken

While Americans have been reeling over the shocking outcome of our presidential election, Cubans are experiencing perhaps even greater vertigo as a result of the surprise victory of Donald Trump.

As the saying goes, “When the U.S. sneezes, the rest of the world gets a cold.” Or perhaps the old Mexican adage is more appropriate to the situation Cubans find themselves in: “Poor Mexico! So far from God, but so close to the United States!”

Cubans went from a largely acrimonious relationship with the U.S. prior to December 2014, to one of unprecedented “hope and change” during the past 22 months under bilateral efforts to achieve diplomatic normalization between the erstwhile adversaries, to one of great trepidation and uncertainty over the past week given the president-elect’s campaign promise to “cancel Obama’s one-sided Cuban deal.” President Raúl Castro perfectly captured the moment’s ambivalence for Cuba by quickly sending the president-elect a brief note of congratulations while simultaneously ordering a five-day military mobilization.

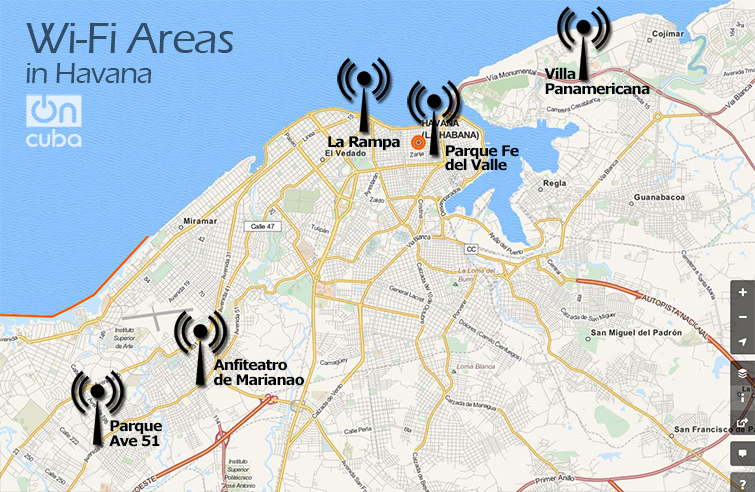

In my more than half-dozen trips to the island over the past year, I have noted a palpable, ebullient expectation among Cubans for a better, more prosperous future under Obama’s “new rules” of engagement. This was especially pronounced among Cuba’s emergent entrepreneurial class, which includes old school cabbies in their even older school American cars, hip app designers in Cuba’s surprising tech start-up scene, and some of the many restaurateurs behind the island’s surging circle of “paladares” (private, home-based restaurants) which now number more than 1,800.

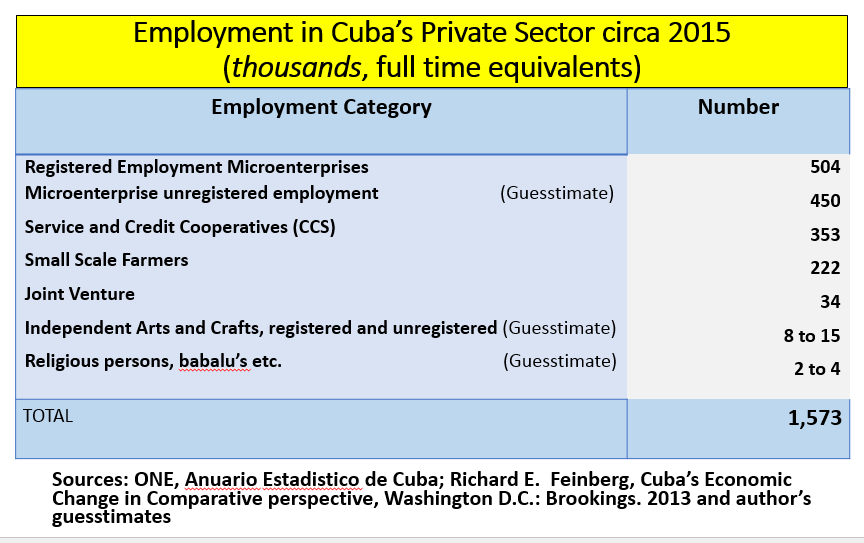

This hard-won hope was also born of Cuba’s own “new rules” introduced in late 2010 under President Raúl Castro aimed at expanding the island’s long-suppressed private sector. However, I also found that most entrepreneurs were under no illusions that the Cuban government would be fully lifting its own counter-productive “auto-bloqueo” or internal embargo against grass-roots entrepreneurial innovation and inventiveness any time soon.

This sense of rising hope inside Cuba reached its climax in Obama’s brilliant deployment of soft power during his historic state visit to the island in March 2016. Many Cubans identified with this youthful, optimistic, and eloquent African-American family man endowed with both a sense of history and of humor much more than with their own waxworks of old white ideologues.

However, Cuba’s old guard realized that Obama’s charm offensive had begun to fatally undermine their own authority and undercut their long-effective use of the U.S. boogeyman as a scapegoat for their own economic failures and as a justification for their continued political authoritarianism. In response, the Cuban leadership has spent the past eight months constantly reminding Cuban citizens of the continued U.S. existential threat to Cuban sovereignty under the Revolution and simultaneously dashing their hopes for a better, more open and prosperous future by stepping up detentions of peaceful political opponents and independent journalists and slowing economic reforms to a manageable trickle.

The clearest example of the Cuban government’s efforts to lower expectations has come on the economic front. First, April’s Seventh Party Congress included no new resolutions about deepening or expanding much needed market-oriented reforms apart from a vague reference to studying the possibility of granting status as legal businesses to a portion of the half-a-million strong micro-enterprise sector. Nothing has come of this idea in the intervening seven months.

Second, price controls have been reimposed in the private agriculture and transportation sectors, reducing incentives for greater production. Third, this past summer saw the government scale back economic growth estimates for 2016 to under 1 percent and impose severe energy saving and cost-cutting measures across the state sector due to a liquidity crisis and the Venezuelan debacle.

Finally, the issuing of new licenses for Havana’s surging private, home-based restaurant sector were suspended for six weeks in the fall in order to root out legal violations such as providing bar services and live entertainment without permission, obtaining supplies from black-market sources, staying open past the state-imposed 3 a.m. closing time, and tax evasion. Some have even been accused of doubling as sites of prostitution and drug trafficking and shut down.

show chapters

However, the government has so far not delivered on its promise to provide affordable access to wholesale markets for these restaurateurs nor has it allowed them to legally import supplies from abroad or expand beyond the arbitrary limit of 50 place settings. Moreover, the tax system for the private sector provokes “creative bookkeeping” by imposing a rigid 40-percent deduction limit for business often burdened by much higher supply costs due to Cuba’s environment of chronic scarcity. It also imposes a labor tax on any more than five employees disincentivizing legal hiring.

To add insult to this injury, the moribund network of their state-run competitor restaurants do enjoy access to wholesale markets and suffer no seating or size restrictions or employment taxes. Especially frustrating for Cuban entrepreneurs is the fact that this emphasis on law and order comes in the context of shrinking output in the state enterprise sector, a looming emigration crisis with record numbers of new Cuban arrivals in the U.S., and in the midst of a tourism boom that the state hospitality sector has proven unable to absorb.

As Cubans like to say: “¡No es fácil!” (It ain’t easy!)

President-elect Donald Trump could follow the recommendation of some Congressional Republicans by adding his own isolationist wind to the already full sails of the Cuban government’s rigid control that attempts to keep Cuban entrepreneurs in their frustrated and impoverished places. Or he could send Cuba’s business pioneers a message of support and solidarity as they attempt to build a more prosperous future by continuing America’s historic opening to Cuba that aims to empower the island’s mergent capitalists through engagement, investment, and trade.

For someone who campaigned as a anti-politician who would bring a hard-nosed business sense to Washington, Cuba presents Trump with a golden opportunity to place economic pragmatism and the tangible benefits it would bring to citizens of both countries over the out-dated and counterproductive Cold War ideology that undergirds the embargo.

Commentary by Ted A. Henken, an associate professor of Sociology and Latin American Studies at Baruch College, City University of New York and co-author with Arch Ritter of the book “Entrepreneurial Cuba: The Changing Policy Landscape.” He is a past president of the Association for the Study of the Cuban Economy (2012-2014). Read his blog and follow him on Twitter @ElYuma.