The quasi-private restaurants in the Barrio Chino have enjoyed a cultural exemption from the controls placed on normal “paladars” or restaurants. They have faced no 12 chair size limitation. They emerged some time ago as dynamic, large, diverse and efficient restaurants – indeed, the best in Havana. They are a living example of what many sectors of the Cuban economy could become if the tight restrictions and toxic tax levels were all made more reasonable. This is not yet happening. (Photo by Arch Ritter 2008)

.

The quasi-private restaurants in the Barrio Chino have enjoyed a cultural exemption from the controls placed on normal “paladars” or restaurants. They have faced no 12 chair size limitation. They emerged some time ago as dynamic, large, diverse and efficient restaurants – indeed, the best in Havana. They are a living example of what many sectors of the Cuban economy could become if the tight restrictions and toxic tax levels were all made more reasonable. This is not yet happening. (Photo by Arch Ritter 2008)

.

By Arch Ritter

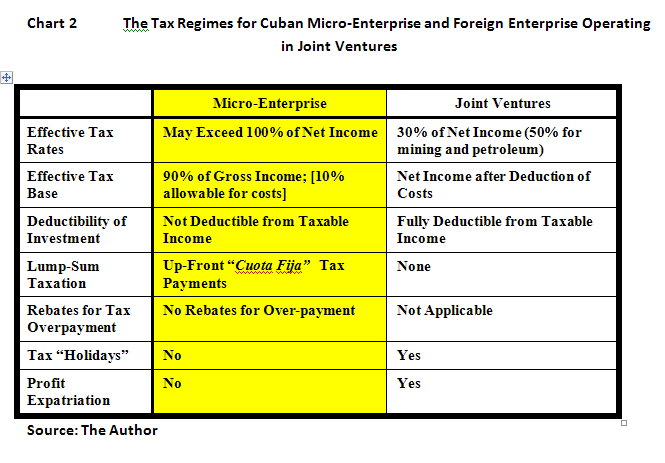

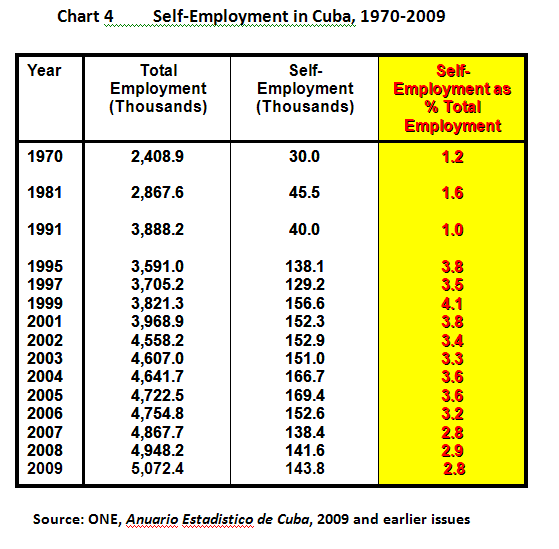

In October 2010, Raul Castro’s Government increased the size limitation on private restaurants from 12 to 20 chairs. This was part of a broader reform package designed to shrink the state sector ultimately by about 1 million workers or 20% of the labour force and to re-absorb them into an expanding small enterprise sector. The 20 chair rule however is symbolic of the positive but timid character of the reforms undertaken so far.

This is an amazing and ironic reversal of fortune for Cuba’s private sector. Small enterprises were almost eliminated in the 1960s, were liberalized from 1993 to 1995 and then were stigmatized and contained by onerous regulations and taxation. Now they are supposed to save the economy, generating jobs, higher productivity and higher living standards than was possible under the old system. 9Raul apparently has even more faith in the small enterprise sector than I do!)

Fidel Castro’s 50-year attempt to construct his own variety of “socialism” is being repudiated and abandoned by his own brother and by the Cuban Government. This is an obvious humiliation for Fidel, even though the genuflections in the media and official documents – including even the “Linamientos” – continue.

Firing one million state sector workers looks risky and brutal. Hoping that they will somehow be absorbed in the small enterprise sector looks like wishful thinking. In other contexts this approach would be labeled “neo-liberal”! Will the laid-off workers have the abilities and aptitudes necessary to start their own businesses?

But the biggest question is whether the small enterprise sector can create 500,000 jobs by March 30 and ultimately one million new jobs. As of November 28, half way through period when the lay-offs are to occur, only 45,000 new self-employment licenses had been issued, with 43% going to retirees rather than those in the labor force. This process is off to a slow start but perhaps it will accelerate.

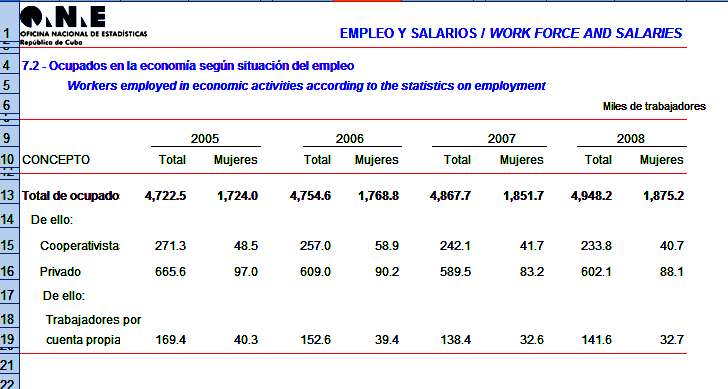

The regulatory and tax regimes under which small enterprise operated from 1995 to 2010 were designed to contain its growth, to keep enterprises tiny, and to limit the incomes of the self-employed. Now the tax and regulatory framework has been liberalized somewhat:

- Licensing has been broadened.

- Rental of facilities from citizens or the state is easier.

- Sales to state entities are now possible.

- Use of banking facilities and bank credit will be possible.

- Permitted activities have been increased.

- Some regulations have been eased.

- Punishments for infractions have been eased. Virtually all of the old ‘infracciones’ continue to punished by the same fines as before. But the seizure of equipment and the retraction of licenses have been dropped.

- Imported inputs will become accessible for small enterprise at wholesale prices.

But tight limits on self-employment remain.

- Professional activities are prohibited.

- Intermediaries are prohibited and each producer is supposed to be the seller of his or her output.

- Petty restrictions such as the 20 chair rule continue.

- Tight limits continue on the hiring of employees.

- Advertising remains prohibited.

The tax regime has been slightly relaxed but is still problematic. Small enterprises face five taxes: a sales tax (10%), a tax on hiring employees, social security taxes, a public services usage tax, and an income tax (that rises to 50% of income above 50,000 “old” pesos or about $2,000.00 per year.) For the calculation of the income tax, deductible costs of production from total revenues are limited to 10% for simpler enterprises up to 40% for larger enterprises. This means that for a restaurant with actual costs of production of 80% of total income, the tax on actual net revenue exceeds 100%. The tax on hiring an employee is 37.5% of the average monthly wage for Cuba.

For very small-scale activities, an up-front monthly licensing fee that constitutes a simplified tax payment is required.

This revised regime is an improvement over the previous system. It may induce some enterprises to come up from underground and may promote the establishment of some new enterprises. But, on the other hand:

- The high effective tax rates will kill off many potential enterprises and promote continued non-compliance.

- The 37.5% employment tax will limit hiring.

- The numerous controls and limitations on small enterprise will continue to “stunt” them so that they remain inefficient, wasting human and material resources.

It is therefore unlikely that small enterprise will expand enough to absorb one million redundant workers. By stunting the small enterprises, the possibilities of raising productivity, real incomes and ultimately living standards will also be limited

What happens then? Perhaps the “Fidelistas” could proclaim victory and halt or reverse the reform process. This is unlikely because the old “Fidel” model is discredited by events and by Raul himself. Moreover, Raul’s appointees now dominate the Council of Ministers. His military colleagues hold many key posts in the economy.

More likely, Raul’s Government will conclude that job creation should precede the lay-offs, not vice versa and that their expectations regarding job creation in the small-enterprise sector were overly optimistic. They might then slow down the lay-offs and in time liberalize the tax and regulatory framework.

Raul Castro is finally emerging from 60 years in his elder brother’s shadow. Perhaps he is thinking of his own historical legacy. “History” will never “absolve” Fidel, but it might absolve Raul if he sets Cuba on a course towards a workable economic system – not to mention human rights and meaningful pluralistic democracy.

Since its liberalization in 1993, the production of arts and crafts, largely for the tourist market, has expanded immensely and the quality and diversity of the products has improved greatly. It is now a major source of foreign exchange for Cuba, though statistics on this do not seem to exist. This sector provides another living example of the improvements that could be made in the small enterprise sector generally if it was liberalized appropriately. Above, a photo of the crafts market near the Cathedral on Avenida del Puerto, by Arch Ritter, 2008.

Since its liberalization in 1993, the production of arts and crafts, largely for the tourist market, has expanded immensely and the quality and diversity of the products has improved greatly. It is now a major source of foreign exchange for Cuba, though statistics on this do not seem to exist. This sector provides another living example of the improvements that could be made in the small enterprise sector generally if it was liberalized appropriately. Above, a photo of the crafts market near the Cathedral on Avenida del Puerto, by Arch Ritter, 2008.

Photographer, at the Capitolio circa 1996, (Photo by A, Ritter)

Photographer, at the Capitolio circa 1996, (Photo by A, Ritter)