Published originally by NACLA (https://nacla.org). This is the last installment of a NACLA series on Cuba’s constitutional reform

Arturo López-Levy is the Bruce Gray Fellow and Visiting Assistant Professor of International Relations at Gustavus Adolphus College, Minnesota. He worked as a political analyst for the Cuban government until 1994. He is a co-author of Raúl Castro and the new Cuba: A Close-Up View of Change (McFarland, 2012.

Arturo López-Levy

Arturo López-Levy

During his time as president, Raúl Castro announced a series of reforms. [3] One of these was to overhaul Cuba’s 1976 constitution [4], which was drafted at the height of Cuban socialism and has long been out of sync with the country’s post-Soviet reality. In July, Cuba’s National Assembly unveiled a proposed version for the new constitution [5]. This draft will undergo a process of public debate throughout the fall and should be ratified in February 2019.

The constitutional reform has intensified debates on the island about rights, citizenship, and the new economy. This essay forms part of a running forum NACLA is hosting to offer a range of views on this crucial process at a critical moment in Cuban history.

In this essay, political scientist and international relations expert Arturo López-Levy explains how the constitutional reform reflects the goals and expectations of a new generation of the Cuban political elite.

Michelle Chase (MC): In broad strokes, what are the most relevant changes proposed in the new draft of the Constitution?

Arturo López-Levy (ALL): If people outside Cuba want to understand the current process of constitutional reform in Cuba, they should look at the relevant terms of the debate and balance of power within the island rather than impose prescriptive and sometimes utopian views about democracy from the outside.

The first thing I would caution is that we should pay attention to the framing of this debate. While many outside observers, dissidents, opposition, and exile intellectuals focus on substantive issues of liberal democracy (such as the right to organize political parties, freedom of association and expression, etc.), the framing of this debate within Cuba’s political structures is mostly focused on procedures and institutions (term limits, decentralization, separation of a new presidency of the republic, presidency of the Council of State, and premiership and legalizing new institutions and practices of the new economy.)

This is hardly a surprise. Facing the passing of the generation who made the Cuban revolution in 1959, the goal of the Cuban elite is improving the collective character of the leadership and the sustainability of the one-party system. There is a new generation of leaders rising in Cuba, but there is no evidence to suggest that they will dismantle the monopoly of the Cuban Communist Party (PCC), establish an independent judicial system, or willingly adopt a free press. This fact has made many observers of Cuba’s political reform skeptical about the prospects for democratization in Cuba. That is why they dismiss the relevance and implications of the debate that is taking place as non-consequential. The problem with these analysts is that they are imposing their own priorities and values without observing the process on its own merits. In contrast, a good analysis should emphasize the magnitude of the institutional change being proposed, and how a change in these institutional procedures can produce substantive changes, even if unintentionally, in the long run.

From an institutional point of view, the proposed reforms to Cuba’s current constitution represent a fundamental political liberalization of the current system. The new Carta Magna represents explicit and implied changes of utmost importance in the economic realm and the organizational structure of the Cuban state.

In terms of explicit changes, the proposed amendments redefine the character and goals of the Cuban state. The proposed constitution drops the goal of “building a communist society” and ratifies the adoption of a new model of a mixed economy in which not only private property is legalized but also the role of the state sector in the Cuban economy changes. This goes farther than reforms introduced in 1992, which opened the possibility for some expansion of private property in the country but explicitly excluded some sectors of production from privatization. That list disappears in the new project. This change does not mean that the Cuban state now has a “neoliberal orientation,” as some have argued, but it does legally empower the government with discretion to decide what to privatize, how and when.

The draft constitution also lays out changes in the structure of the state that open the gates for a substantial future decentralization. The new constitution redefines the role and mode of election of the provincial governors and their relations with the municipalities. At the national level, the new text proposes the creation of a presidency, as the top official of the country, centralizing in that office many functions that Fidel Castro has said in the past that should be distributed in a council of notables and representatives of the social organizations under the tutelage of the communist party (the Council of State). Together with this new office of the presidency, the constitutional proposal includes the separation of functions and position of the president of the Council of State and prime minister. This is not a separation of power, as some uninformed observers suggest, but a clearer distribution of functions. The prime minister is subordinate to the president, who is also supposed to be the leader of the party, but the premier’s performance and legacy will be essentially assessed by his performance (better economy, welfare, etc.), not in ideological terms.

MC: How was this draft produced? Who exactly contributed to it and how do we see those interests in the draft?

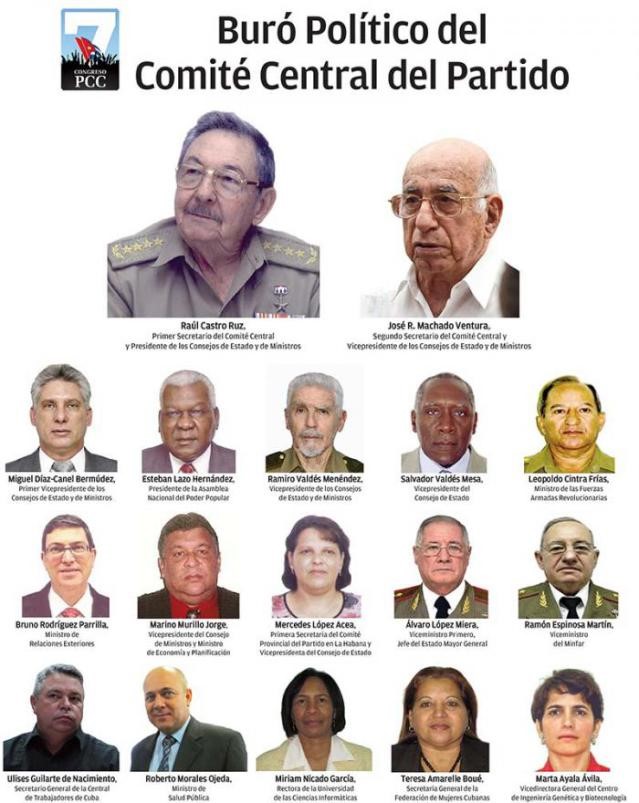

ALL: The politburo of the Communist Party created a commission six years ago that worked on a blueprint of the most important proposals. Then, at the end of the legislative term in December 2017, the National Assembly created a commission of deputies that included many of the members of the first commission created by the party, plus some relevant scholars of law, history and other matters, and representation from official regional and mass organizations. In terms of generations, the commission showed an interesting mix of old and new blood (in both political and demographic terms).

Most of the members of this commission are openly and inextricably tied to the orthodox party line of the PCC. The group was not composed of the country’s most prominent jurists, constitutional law scholars, experts, or intellectuals. They were competent loyalists who exercised their power as agenda setters in the dark, with no transparency.

This fact disavows any fiction of separation between the state and the party but it also confirms the relevance assigned by the leadership to the constitution making process and the anticipated changes for the political future of the country. This is a loyalist commission that is conscious of the need for renewal within the limits of the system and took seriously the challenge of legitimation and adaptation under the new conditions of the world and Cuban politics and economy.

The commission submitted its proposal to the National Assembly, which debated it and approved it for submission to the general public as a project for debate. Then a process of discussion throughout the whole country began, in every neighborhood or place of employment. In addition, for the first time and creating an interesting precedent, a website hosted by the ministry of foreign relations is collecting comments from emigres. This final project will supposedly be submitted to a referendum during the first half of 2019.

The process of debate serves many purposes beyond the pursuit of some domestic and external legitimation. One of the most important goals is the collection of information about the positions not only of the antagonists but also about those who are associates in different degree with the system. The discussion allows also some cooptation of civil society’s demands and elites opening space for them within the governing coalition. It also allows the historic generation of the revolution to test the persuasive capability and attraction of the different positions of those rising within their ranks.

MC: Why is the Constitution being revisited at this time? How is it related to Raúl Castro’s reforms, the new presidency of Miguel Díaz-Canel, etc.?

ALL: This proposal of constitutional reform is part and parcel of the gradualist and incrementalist approach to economic and political reform adopted by Raúl Castro. An important part of the new project has to do with the political conception about what type of state Cuba will be. The new Article 1 introduces the notion of a socialist “rule of law,” better interpreted as a socialist rule by law. Although this term has been mentioned several times since 1959, it has never been elevated to the rank of a constitutional principle. The idea—as presented by the most outspoken voice in the commission, the chief of the secretariat of the Council of Ministers Homero Acosta—emphasized constitutional obedience and observance over arbitrary power.

Does talking about a “rule of law” socialist state and the reintroduction of guarantees of important rights such as habeas corpus represent the adoption of a judiciary independent from the Communist Party? Obviously not, but that does not mean that when Cuban leaders speak about a “more democratic system” or a “democratic party of the Cuban nation” or rapprochement with patriotic emigres, they are just babbling demagoguery. On the contrary, this is an acknowledgment that, without the complement of political liberalization, the success of economic reform is at risk. Facing the ideological position presented by former dean of the law school of the University of Havana, Jose Toledo Santander who defended the proposition that the Communist party was above the National Assembly and the constitution is what the party- particularly its Political Bureau- say it is; Acosta proposed a different scheme in which the party lead the discussion of the constitutional reform today and then becomes the main guardian of its strict application in accordance with the will of the people who is the ultimate holder of Cuban sovereignty.

The new president Miguel Díaz-Canel and his team are conscious of the potential problems that a more open Cuba can bring. Let’s not forget that political liberalization, not to mention democratization, can be a destabilizing process for a system like Cuba’s. But Díaz-Canel and the new generation of leaders know that accelerating the reforms adopted under Raúl is their best chance. Many factors are pushing in this direction. The one-party state’s old pillars of legitimacy (personal charisma, the appeal of communist paradigms, the appeal of social equality) have declined. It is also clear that the current political structure is inadequate to cope with challenges associated with these reforms, such as the rise of inequality, the overlapping of race and class in the income gap, the increase of corruption and the divisions between urban and rural areas, tourist and non-tourist sectors of the economy, and sectors that benefit from remittances versus those that do not.

In general, these reforms show that president Díaz-Canel and his generational team are setting the political agenda of the country. Some of these leaders have been candid about the fact that the constitutional reforms are updating the legal framework of the country because politics and law have lagged behind the economic and social changes in the country. This was never a major concern of Fidel and Raúl Castro, or the generation of the so-called “historicos.” It confirms that the new generation of leaders is acting with the support of the old generation but is pressing their own issues forward.

MC: Is it fair to say that the new constitution is moving Cuba toward a more republican, or liberal, concept of citizenship?

ALL: Yes, in the margins. In the liberal sense, it proposes a rule by law, not a rule of law. This is better than what exists now but it is not based on an open and transparent competition of political views within the paradigm of the universal declaration of human rights. In the republican sense, the assessment is more complex. The new project creates a better separation of functions between president and prime minister and improves some mechanisms of horizontal accountability and decentralization. At the same time, by transferring to a president of the republic the previous functions of the council of state, the new constitution will strengthen the individual power of the top executive. This could open the door to bouts of Latin American caudillismo down the road.

However, liberal democracy or republicanism in the western style should not be the main criterion to measure the progress of Cuban political development. Cuba democratizes according to its own history and culture. The concept of political liberalization is better fitted to deal with the transformation taking place in Cuba because it emphasizes issues such as the expansion of choices and human rights as international standards. For instance, the expansion of rule by law provides the country with better institutional mechanisms (courts, police, prosecutors, etc.) to cope with an eventual democratization, regardless of the government’s intention to use it to strengthen one-party rule. In a worst-case scenario, non-liberal reformers will be doing the right thing for the wrong reason. The result could be positive.

MC: What implications do all these changes have for U.S. policy toward Cuba?

ALL: If the international community, particularly Latin America and the United States, want to have a realist policy of democracy promotion towards Cuba, it is essential for their policymakers to abandon false presumptions about short-term democratization in the liberal sense and educate themselves about the real and relevant framework, choices, and scenarios within which Cuba is discussing its constitutional reforms. In such a critical hour, the policies of the Trump administration are the model of what not to do. If they continue to adopt a narrow vision about democratization and rights, the role of most international actors, their positions and interactions will be counterproductive.

At a critical time of debate, which will shape how Cuban politics will unfold and whether there will be more opportunities for democratization in the future, the role of the United States is important mainly for what it shouldn’t do. Cubans will decide their own destiny within the context of a nationalist culture strengthened by the 1959 revolution. If Washington insists on treating the new government as mere continuation of the previous generations, trying to play favorites within Cuban politics and interfering in Cuba’s internal affairs, American policy will be very counterproductive to Cuba’s political development and even detrimental to America’s national long-term interest in a peaceful, stable, democratic, and market-oriented Cuba.

The Trump administration has chosen to reaffirm policies of hostility despite all the promising signs for marketization and political liberalization of more engagement during the last two years of the Obama administration. Washington should reconsider the way it engages with a changing Cuba. It should look at this process of constitutional reform with a flexible vision about the positions and motivations of all Cuban actors, including non-liberal reformers in the government. Rather than dismiss the relevance of the intergenerational transition of leadership, it should engage the new president Miguel Díaz-Canel with dialogue and dignity using this critical juncture for a new beginning and facilitating the deepening of the reforms, not repeating the hostility role so fruitful to the most conservative elements in the Cuban government ranks.