by Samuel Farber*

Original Article: Controversy About “Centrism” In Cuba. HAVANA TIMES, September 2017.

The editors of Cuba Posible, Roberto Veiga Gonzalez y Lenier Gonzalez Mederos.

The editors of Cuba Posible, Roberto Veiga Gonzalez y Lenier Gonzalez Mederos.

As most people know, the Cuban mass media – radio, television, newspapers and magazines – are totally controlled by the state and they exclusively publish or broadcast content that closely follows the “orientations” of the Ideological Department of the Central Committee of the Cuban Communist Party (PCC.) It is through mechanisms such as these that the government’s ordered “enforced unanimity” continues to prevail in the Caribbean island.

Yet, in spite of censorship, there exists a relatively free space created by the Internet. Although in Cuba access to the Internet is expensive and continues to be among the lowest in Latin America and the Caribbean, it has nevertheless increased, thus allowing for the existence of many publications and “blogs” critical of the regime from different vantage points.

The most important in Spanish of these publications is Cuba Posible, edited by Roberto Veiga Gonzalez and Lenier Gonzalez Mederos, two Cuban Catholic disciples of the deceased Carlos Manuel de Céspedes y García-Menocal, a progressive priest who was General Vicar of the Archdiocese of Havana. Until a few years ago, Veiga and Gonzalez Mederos were the editors of Espacio Laical, sponsored by the Félix Varela Cultural Center of the same Havana Archdiocese, but they were fired by the Catholic hierarchy that no longer wanted to support the political line of the editors.

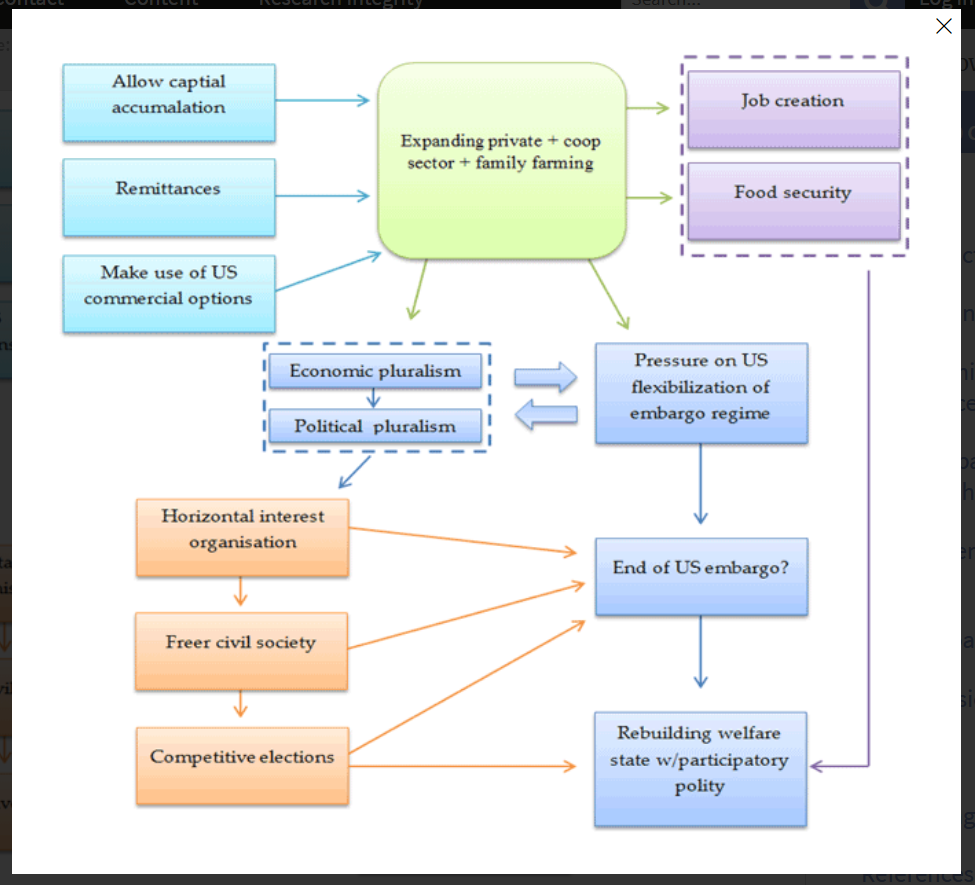

Broadly speaking, Cuba Posible could be characterized as social democratic because of its support for a mixed economy, which in reality would end up as a market economy subject to the imperatives of competition and other economic laws of capitalism given the lack of workers’ control and a democratic planning of the economy.

With respect to the political system itself, Cuba Posible presents a pluralist perspective and has occasionally criticized the one party state as a questionable political system without making its opposition to it a central feature of its publication.

For the socialist and democratic left, those politics are troublesome enough in and of themselves. But they become even more problematic when coupled with Cuba Posible’s stated intent to act as a “loyal opposition” to the regime. In the first place, no such thing as a “loyal opposition” is possible in a system that, as a matter of political principle rejects the mere possibility of an opposition; it is even less possible that such an opposition, however loyal, can come to power through elections or any other peaceful means. Secondly, such intent injects into the publication a conciliatory tone when indignation is the most appropriate response to the government’s abuses.

It should be noted, however, that Cuba Posible continues to include among its collaborators people who represent a broader political perspective than that of its editors. And in any case, Veiga Gonzalez as well as Gonzalez Mederos have the absolute democratic right to submit their views to the consideration of the Cuban people, whether in the Internet or in the mass media, a right that is, of course, rejected by the regime stalwarts who have lately closed ranks against them and their publication accusing them of the sin of what these stalwarts have labeled as “centrism”.

What are those who speak about “centrism” saying?

Several months ago, a group of writers, who for some time have been agitating, supposedly on their own account, for a “hard line” position in defense of the Cuban regime, began a campaign against Cuba Posible and other moderate critics of the Cuban regime. The most important of those hard line writers has been Iroel Sanchez in his blog La Pupila Insomne (https://lapupilainsomne.wordpress.com), where he recently reproduced a whole book titled El Centrismo en Cuba: otra vuelta de tuerca hacia el capitalismo [Centrism in Cuba: Another turn of the Screw towards Capitalism].

The book includes his contributions as well as those of many of his co-thinkers. It is an open attack against what Sanchez and company call “centrists,” accusing them of using their moderate critique of the government as a mask to subvert and eventually overthrow the “socialist” system in Cuba.

Besides branding that supposed strategy as “right-wing nationalist” and “social democratic,” Iroel and his associates also brandish against those critics the term “third way,” which in reality has nothing to do with right wing nationalism or with social democracy, but refers instead to the policies espoused by Tony Blair, who far from being a social democrat, was a neoliberal trying to subvert the welfare state and the social democratic character of the British Labor Party. For Iroel and his hardliners, however, this doesn’t matter: there is no difference between right-wing nationalism, social democracy, and neoliberalism.

Of all the terms wielded by Sanchez and company against the opposition, the one that they really focused on was “centrism.” They wield it in a purely topographic sense referring to a location in between two extremes, capitalism and communism. Curiously, the supposedly communist Iroel Sanchez seems to ignore that in the political traditions of revolutionary Marxism and Communism, the term “centrism” refers to those political parties that, especially in the period 1918-1923, were more radical and to the left of Social Democracy but kept to the right of the Communist parties.

Among those “centrist” parties were the German Independent Social Democrats – a left-wing split from German Social Democracy (SPD) – and several other European parties that came together in the 1920s to form the so-called “Vienna International,” which, significantly, was also referred to as the “Two and a half International.” For the Communist International, these parties might have talked about socialist revolution, but in reality they were reformists and even counterrevolutionaries.

While centrism within that Marxist tradition referred to a specific phenomenon – left-wing radical groups that broke with Social Democracy but did not become Communist – Sanchez uses the same term to paint over with the same brush the wide political spectrum of political orientations between capitalism and Communism. If you are not 100% with the regime, your actual politics does not matter: and you are, by definition, an anti-revolutionary “centrist.”

Even in purely topographic terms, the characterization of the Cuban opposition and critics as “centrists” is highly questionable, because it assumes, as a political axiom, that the Communist parties in power are in fact left wing. This is how, by definition, Iroel and his people get to identify the left with a system that in reality is a class society based on state collectivism, where the state owns the economy, and manages it through the control mechanisms of the one-party state. To be part of the ruling class depends on the position that individuals occupy in the party-ruled bureaucracy. This type of power is hostile to democracy, civil and political rights, and especially to the working class and popular control of the economy.

Fortunately, there are other far better conceptions of what the left means. For Jan Josef Lipsky, for example, a leader in Poland, of the Workers’ Defense Committee (KOR) in the 1970s, and of Solidarity in the 1980’s, the left is, as he explained in KOR. Workers’ Defense Committee in Poland, 1976-1981, an attempt to reconcile equality and liberty: “…being on the left” is “an attitude that emphasizes the possibility and necessity of reconciling human liberty with human equality, while being on the right…may mean sacrificing the postulate of human freedom in favor of various kinds of social collectives and structures, or foregoing the possibility of equality in the name of laissez faire.” (180)

But Iroel Sanchez and his associates defend the one-party state as the only political system compatible with socialism. They don’t even mention that Raul Castro’s “monolithic unity” proclaimed years ago disregards the profound differences in political power associated with class, race and gender in the “actually existing” Cuban society.

It is precisely because of that power differential, that those groups and individuals without power in society – workers, peasants, Black people, women, and gays among others – need the freedom to organize independently into associations and political parties to struggle for their interests. For this to happen it is necessary to abolish the political monopoly of the PCC, consecrated in the existing Constitution, through its mass organizations like the CTC [Worker’s Confederation] and the FMC [Women’s Federation], which blocks any independent attempt by workers, women and other groups to defend themselves.

Once deprived of its constitutionally mandated monopoly, and thus, of all the privileges it appropriated onto itself during its long lasting control of public life, the PCC could become an authentic political party, a voluntary organization materially supported by the dues and donations of its members and sympathizers. It would then function as one of many political parties representing the conflicts and divisions within Cuban society. To the extent that these parties represent the interests of the classes and groups that would emerge in a changing society, it would be impossible – and undesirable – to limit their number through legal mandates, or through administrative or police methods.

Who are the people attacking the “centrists”?

Some people in the opposition regard Iroel Sanchez and his stalwarts as “extremists.” But this is not an appropriate term: historically, there have been many “extremists” who did the right thing. The pro-independence Cubans of the War of Independence (1895-1898) could have also been accused of “extremism” since they rejected both the “volunteers” and “guerrillas” who supported Spanish colonialism (equivalent to the Right of those years) and the Autonomists (the moderates of that period).

Instead, Iroel and company are hard line Stalinists, as they clearly demonstrate in their book. Thus, in his contribution titled “Una respuesta para Joven Cuba” [An answer for the Joven Cuba blog,] Javier Gómez Sánchez lashes out against the blog under that title, a blog that has been frequently critical and fairly honest but clearly pro-government, as if they were just another group of “centrists.”

The content and inquisitorial tone of Ileana González in her contribution titled “Al Centrismo Nada” [Nothing for Centrism] does not fall far behind Andrey Vyshinsky’s, the prosecutor of the Moscow Trials from 1936 to 1938. The extremely detailed information about opposition persons presented in various articles in this book also suggests that many of its contributors are State Security agents or close collaborators of that repressive body.

It is worth noting, however, that these Stalinists do not seem to have gelled into a hard line political tendency within the PCC, as was the case, for example, of the “Gang of Four” that attempted to control the Chinese Communist Party after Mao’s death, but was quickly eliminated by Deng’s forces. They don’t even resemble Fidel’s Support Group at the beginning of this century, to which the Maximum Leader conferred a certain degree of operational and administrative power. Iroel and his group are no more and no less than propagandists in the service of the PCC. That is all.

What are the purposes of the campaign against “Centrism”?

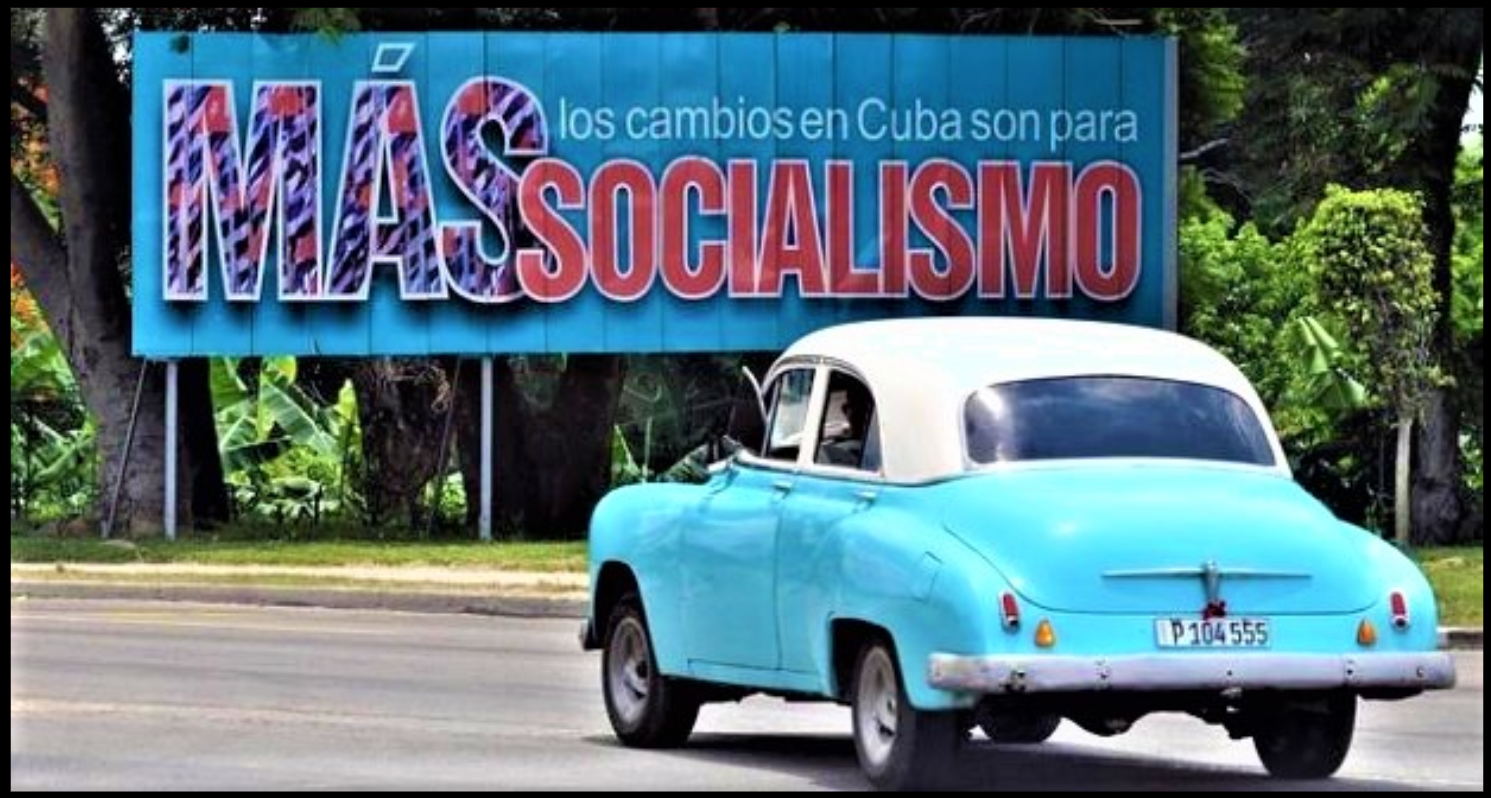

The Cuban government initiated and is using this campaign to draw a line in the sand of what is and is not permissible. But it is not doing it itself through its official press and broadcasting stations to avoid sowing more doubts about the authenticity and durability of Raul Castro’s economic reforms and relative political liberalization.

Long term, the regime is using this campaign as an attempt to close the ranks of the party and the country with another call in the style of the “monolithic unity” of former years in preparation for the foreseeable physical disappearance of the historic leaders of the revolution in the next five to ten years, and for the problems that this can create for a fluid transition of power.

The call to “unity” has become ever more urgent with the gradual but definitive increase of Internet access, especially among the youth, the professional and technocratic strata, and among those with a university education who generally have a greater access to the Internet. The information acquired through those channels can potentially undermine the political loyalty to the party and regime. It is not for nothing that practically the entire campaign against “centrism” has been conducted through the Internet, and not in the official press and mass media.

Trump’s repeal of several measures favoring the slow process of relaxation and possible abolition of the economic blockade of Cuba, have not yet eliminated the limited but real softening of the opinion of many Cubans with respect to the United States. This softening was due to Obama’s initiatives easing various restrictions of the US’s criminal blockade, such as increasing the remittances that can be sent to Cuba, resuming regular commercial flights to the Island, and his successful visit to Cuba.

As we know, the official Cuban press has used every means at its disposal to fight that softening of Cuban opinion, which for obvious reasons, the regime considers dangerous to its power. The government’s attack against the so-called “centrist” opposition, is nothing more than another attempt to harden the Cuban people to close ranks around it and to maximize its control through its call to “unity.”

*Samuel Farber was born and grew up in Cuba and has written numerous articles and books about the country. His last book, The Politics of Che Guevara: Theory and Practice was published by Haymarket Books in 2016.

Cuban activist Rosa María Payá with the former president of Costa Rica, Miguel Ángel Rodríguez, in Lima, Peru

Cuban activist Rosa María Payá with the former president of Costa Rica, Miguel Ángel Rodríguez, in Lima, Peru