JACOBIN MAGAZINE, May 1, 2018

BY SAMUEL FARBER

Original Article: Cuba in 1968

In 1960, less than two years after having overthrown the Batista dictatorship, the Cuban Revolution was well on its way to implementing the Soviet model. Most people at that time still supported the revolution. Notwithstanding the recurring shortages of consumer goods and the housing crisis, most Cubans had benefited from the newly established welfare state, which insured an austere but secure standard of living.

Buoyed by that support and by the people’s enthusiastic response to its resistance to US imperialism, the Cuban leadership pursued its foreign-policy objectives with a revolutionary elan absent in the more cautious and conservative Soviet bloc.

Cuba displayed its anti-imperialism with particular vigor in Latin America, where it supported — and often organized — guerrilla groups set on overthrowing dictatorial governments. Fidel Castro’s government devoted extra attention to countries that had severed their ties with Cuba following Washington’s directives. That is, Castro’s militant foreign policy was based not only on its revolutionary ideas also but on the Cuban state’s interests.

This helps explain why Castro maintained friendly relations with corrupt and authoritarian Mexico, the only Latin American country that refused to break diplomatic relations with revolutionary Cuba. In fact, Castro’s government abstained from criticizing Mexico’s crimes, including the October 1968 Tlatelolco massacre.

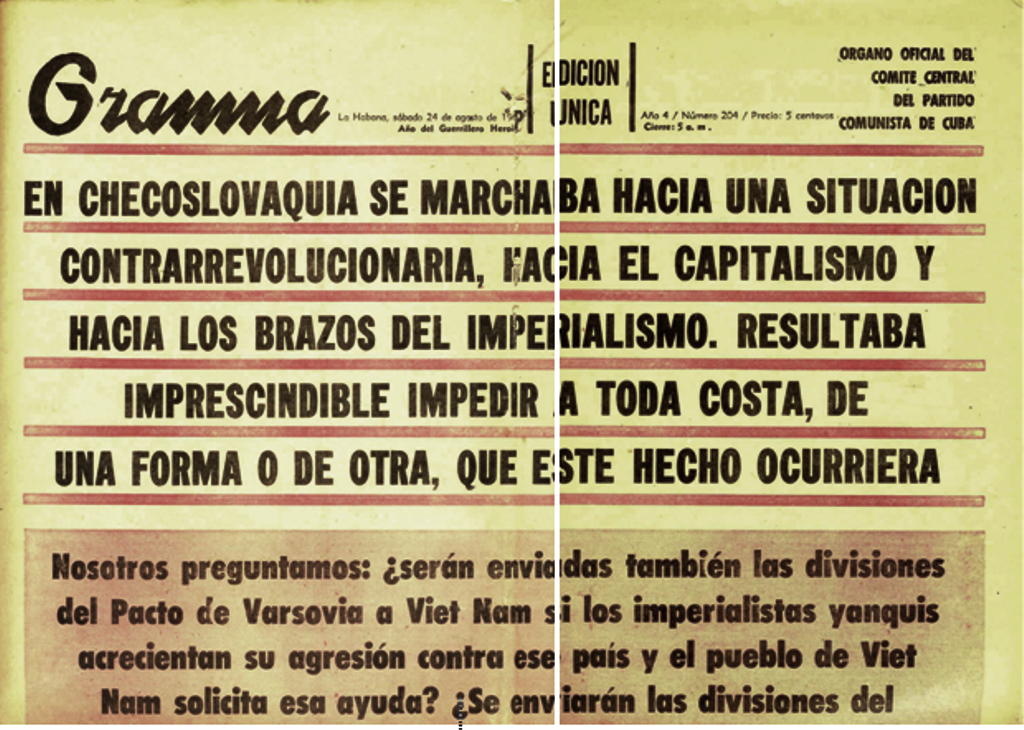

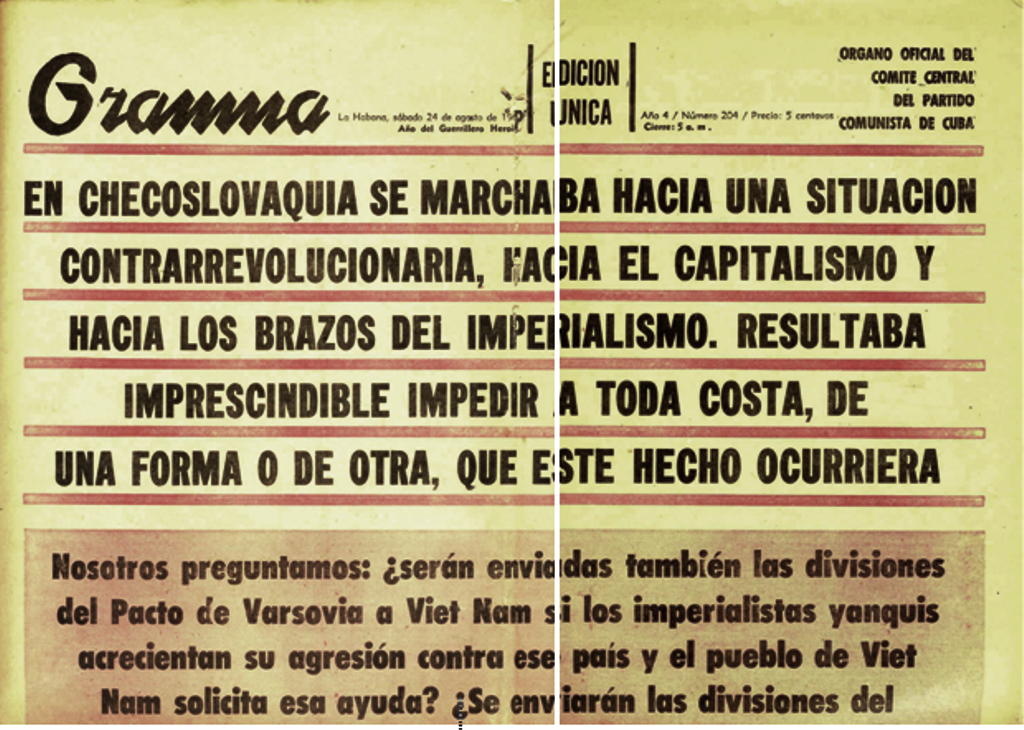

Granma, the official organ of the Cuban Communist Party, adopted a purely “objective” journalistic posture when covering Tlatelolco, allowing it to avoid any critical analysis of the political actors behind the massacre. While the Mexican left was denouncing the murder of hundreds of demonstrators, Granma uncritically reported the “provisional” figures provided by the “official sources”: just thirty dead, fifty-three seriously injured, and fifteen hundred arrested.

Reasons of state also explain why, after a rough start, Fidel established friendly relations with Franco’s dictatorship and why the Cuban revolutionary hierarchy, from its official unions and student organizations all the way to the top, did not support the French May ‘68 movement. Not only did French President de Gaulle refuse to toe the US line against Cuba, but he had also agreed to continue trade, which had became of crucial importance to the island following the American blockade. As with Tlatelolco in Mexico, Granma limited itself to “objectively” reporting the events of May ‘68. It strictly avoided making any political inferences or conclusions.

Despite these contradictions, Castro’s early foreign policy was governed by a set of revolutionary ideas that aimed to establish systems similar to Cuba’s across Latin America. His government supported and organized foco groups on the top-down Cuban model, which produced acrimonious conflicts with the gradualist and pro-Moscow Communist parties in countries like Venezuela and Bolivia. It also caused friction with the Soviet Union itself because Castro’s militancy jeopardized the long-standing agreement between the USSR and the United States, which held that the two imperialist powers and their partners would not intervene in each other’s spheres of influence.

This tension came to a head in 1967, when Moscow began to significantly reduce its oil shipments to Cuba in hopes of pressuring the island into moderating its aggressive foreign policy. But Castro wasn’t swayed. He responded by denouncing the USSR’s friendly overtures to Venezuela and Colombia despite their anti-communist repression. He then refused to send a top Cuban political figure to the celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of the Russian Revolution in November 1967. And, at the celebration of the ninth anniversary of the Cuban Revolution in January 1968, he expressly, albeit diplomatically, connected Cuba’s tightened oil rations to the slowdown of Soviet delivery. The USSR then suspended its supply of military hardware and technical assistance.

When conflict simmered between a reform-minded Communist government in Czechoslovakia and Moscow, many wondered what the Cuban response would be. For months, Granma published very little about Czechoslovakia, entirely ignoring the reformist Prague Spring and its impact on the international left. This changed, however, in mid-July, when the paper began covering the growing confrontation between Czechoslovakia and the USSR in depth.

Most likely, Castro recognized that the key dynamics of the Czech events had shifted. Originally, protesters were calling for internal reform and democratization, which Castro would not want to have publicized on the island. (Likewise, Granmadid not cover the student movements in Poland and Yugoslavia that had taken place in March and June of that year.) But by July it had become clear that a confrontation between Czechoslovakia and the USSR was coming, one that would bring the issue of national sovereignty to the fore. US imperialist aggression made this question particularly important to Castro, and the conflict brewing between Cuba and the USSR only made the issue more urgent.

Granma focused on the external USSR-Czechoslovakia conflict, excluding the internal dimension, and wrote in some detail about other Communist parties’ reactions to the developing confrontation, regardless of which side they supported. It was clear that the newspaper — and by inference Fidel Castro, his government, and the Cuban Communist Party — would not take sides. In fact, it was going out of its way to give equal space to both parties.

But this all changed when Fidel, without having said a word about the conflict, came out in support of the Soviet invasion in August. Granma immediately adopted the Soviet line and started publishing statements from Cuban mass organizations praising Fidel’s support of the invasion.Other steps, designed to appease the Soviets and incur favors, followed. Cuba cut back on its support to Latin American guerrillas, and, in the 1970s, it carried out a rapprochement with the pro-Moscow Communist parties in the region by acknowledging that armed struggle represented only one path for revolutionary struggle. In response, these parties recognized Cuba’s vanguard role in the hemisphere’s anti-imperialist struggle.

This was the beginning of what former Soviet diplomat Yuri Pavlov called the “belated honeymoon” between the USSR and Cuba, which lasted well into the 1980s. In June 1969, the Cuban representative at the International Conference of Communist Parties in Moscow joined the pro-Soviet majority in denouncing China’s “sectarian” position. In return, the Soviet Union sent a flotilla of warships to visit Cuba. An exchange of military delegations soon followed. Marshal Andrei Grechko, the Soviet defense minister, went to Havana in November 1969, and Raúl Castro, Cuba’s defense minister, traveled to Moscow in April and October 1970. The flow of Soviet arms resumed and then increased, and Fidel Castro approved the construction of a deep-water base for Soviet submarines at Cienfuegos.

Mutual state visits came soon after, and Cuba joined the Soviet-led Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA) in 1972. In that period, Cuba turned to Africa as the main focus of its revolutionary foreign policy. There, unlike in Latin America, it shared Moscow’s strategic interests.

While appeasing Moscow, Castro nevertheless preserved his right to disagree with some Soviet policies, making Cuba a junior partner, rather than a satellite, of the USSR. In fact, Castro had staked out this position from the beginning. In his speech supporting the invasion of Czechoslovakia, he not only criticized Alexander Dubcek’s “liberalism” but also the USSR’s policy of peaceful coexistence with the United States. The Cuban leader sarcastically wondered if the Soviets would dispatch Warsaw Pact troops to help defend Cuba from an attack by the imperialist Yankees.

Full Nationalization

That same year, Castro initiated what he called the Revolutionary Offensive, a project aimed at totally nationalizing the island’s economy. The state had already taken over large and middle-sized businesses in 1960, but family-owned operations remained in private hands.

Within sixteen days of the announcement, the official press reported that 55,636 small businesses had been nationalized, including bodegas, barber shops, and thousands of timbiriches (“hole-in-the-wall” establishments). The Revolutionary Offensive gave Cuba the world’s highest proportion of nationalized property.

According to Cuban economist Carmelo Mesa-Lago, some 31 percent of these small businesses were retail food outlets, and another 26 percent provided consumer services, like shoe and auto repair. Restaurant and snack shops represented another 21 percent; 17 percent sold clothing and shoes. The rest (5 percent) were small handicraft establishments that manufactured leather, wood products, and textiles. Half of these small businesses were exclusively owner- and family-operated and had no employees.

Shortly after nationalization, the state closed one-third of the small enterprises. The only private activity left in Cuba was small-farm agriculture, where 150,000 farmers owned 30 percent of the land in holdings of less than 165 acres each.

One of the Revolutionary Offensive’s goals was to shut down the many thousand bars in Cuba, both private- and state-owned. The regime wanted them closed not because of opposition to alcohol but because it believed the bars fostered a prerevolutionary social ambiance, antithetic to the Castro government’s militaristic, ascetic, anti-urban campaigns to forge the “New Man.”

These campaigns began in 1963, when Castro attacked homosexuality and cultural nonconformity.. Hoping to emphasize the state’s centrality to citizens’ lives, he also went after religious dissenters, including Jehovah’s Witnesses, Catholics, and followers of the secret Afro-Cuban Abakuá society. Members of these groups were imprisoned in the Units of Military Aid to Production (UMAP), forced labor camps established in 1965 and disbanded in 1968.

The Revolutionary Offensive’s nationalization of all small businesses was also intended to provide the state with complete control over agricultural output. Many of the expropriated merchants bought farm products at high prices, reducing the amount available for the state.

In addition, it granted the state more power over the labor force. Absenteeism and job abandonment, generated by the lack of consumer goods, had become a major problem. To combat it, the Cuban leadership drafted a law against vagrancy, which it enacted on March 28, 1971. The legislation ordered all adult men to put in a full day’s work and established a variety of punishments ranging from house arrest to internment in forced labor rehabilitation centers. Information regarding its enforcement is unknown.

The Revolutionary Offensive exemplifies Castro’s super-voluntarist, “idealist” approach to socialization. The policy equated private property in general with capitalist private property in particular, a misreading of Friedrich Engels’sSocialism: Utopian and Scientific.

There, Engels distinguished modern capitalism, in which individual capitalists appropriate the products of social and collective activity, from socialism, where both production and its appropriation are socialized. Accordingly, productive property involving collective work is the proper object of socialization, not the individual or family productive unit, let alone personal property.

Besides this confusion, the Cuban government was in no position to take over the distribution of goods and services from small businesses — the nationalization program reinforced, instead of ameliorated, the shortage of consumer goods.

The Ten Million Ton Sugar Crop campaign, planned for January 1969 to July 1970, is another example of Castro’s voluntarist orientation. This extravagant effort never achieved its goal. Instead, it diverted scarce production and transportation inputs, causing serious disruptions to the island’s economy.

As historian Lillian Guerra pointed out, the campaign represented far more than an exercise in voluntarism or “idealism.” It aimed not only “to revive the ‘júbilo popular’ (mass euphoria) of the early sixties and thereby restore the unconditional standards of support for government policies” but, more importantly, “to prove the value of labor discipline and enforce it simultaneously.”

Likewise, as Mesa-Lago pointed out, Castro used the Revolutionary Offensive to mobilize as much of the labor force as possible for production, particularly in agriculture, in order to reinforce labor discipline, save inputs, and exhort workers to increase productivity and do unpaid work. In April 1968, the official union confederation recruited a quarter of a million workers to perform farm labor without pay for twelve hours per day over three to four weeks. Some 2.5 million days were “donated” by workers who spent fourteen weeks on coffee plantations.

These campaigns were all launched in response to that decade’s economic crisis, one that became qualitatively worse with the criminal economic blockade established by the United States in the early sixties. But the bureaucratic and chaotic top-down administration of the economy generated that crisis.

As Andrés Vilariño, a Cuban government economist pointed out, investment inefficiency was one of the principal causes of declining economic productivity in the sixties. For example, expensive imported machinery sat in warehouses and ports for so long, most of it rusted over. Meanwhile, the inadequate supply of consumer goods, combined with the lack of worker control of the production process and the absence of independent unions, engendered a sense of apathy among Cuban workers. The lack of transparency in decision making, not to mention the inaccurate economic information coming from a lower management class fearful of reprisals for reporting bad news, produced bad planning and waste, often aggravated by Fidel Castro’s capricious interventions and micromanagement.

In one telling case, he tried to introduce a new breed of cattle, the F1 hybrid, against the advice of British experts that he himself had brought to Cuba. The project wasted millions of dollars.

New Targets

In 1968, Castro shifted the repression already being deployed on his government’s enemies (even critics from the pro-revolutionary left). First, the government eliminated some of the most excessive forms of punishment, closing, for example, the UMAP agricultural labor camps. Second, government policing efforts zeroed in on any political and cultural expression that deviated from the official party line.

A case in point was the old Communist leader Aníbal Escalante. In 1962, he was purged from the government and party and then jailed for his sectarian attempt to accumulate power by excluding revolutionaries who did not belong to the old pro-Moscow Communist Party from government positions. In 1968, he was again purged and jailed, this time on charges of having formed a “micro-faction” within the Cuban Communist Party critical of Castro’s economic policies. He was also accused of meeting with Eastern European diplomats in order to gain their support. For Fidel — and his brother Raúl, assigned to officially charge Escalante — this “micro-faction” jeopardized their efforts to impose a single line in the party.

The affair demonstrates the disproportion between the supposed offense and the punishment. Not only were many of Escalante’s criticisms of Castro’s economic policies correct — especially with regard to the disastrous ten million ton sugar-crop campaign — but no evidence ever indicated that Escalante and his small group were conspiring to remove or overthrow the Cuban government with or without the support of Eastern European diplomats. The group may have been “unpatriotic,” as the government charged, but its activities were peaceful and therefore subject to public political debate. Instead, the regime, following the Stalinist tradition, turned it into a criminal case.

Castro had thirty-five of the thirty-seven members of Escalante’s group tried by a so-called War Council (Consejo de Guerra), which the government assembled specially to impose stiff sentences. Escalante was sentenced to fifteen years in prison, and thirty-four of his associates were sentenced to terms ranging from one to twelve years. The two remaining members belonged to the armed forces and were therefore referred to the Revolutionary Armed Forces’ prosecutor for processing.

By adopting these separate paths, the government implicitly recognized most of Escalante’s group as civilians, who were supposed to be processed differently from, and under less onerous rules than, the military. Despite this implicit difference, they faced a War Council, where they earned harsher sentences than they might have received otherwise.

Castro also turned his attention to Cuban dissenters in the cultural realm. In January, 1968, the government opened the Havana Cultural Congress, inviting more than five hundred intellectuals from seventy countries to attend, including prominent left-wing social scientists and historians such as Ralph Miliband and E. J. Hobsbawm, well-known Caribbean and Latin American literary figures like Aimé Cesaire, Julio Cortázar, and Mario Benedetti, famous European writers such as Michel Leiris, Jorge Semprún, and Arnold Wesker, as well as left-wing politicos such as several leaders of the North American SDS and SNCC. The congress, which focused on the topic of political, economic, and cultural anti-imperialism, was ostensibly carried out in an open manner. According to independent observers, all the presentations and resolutions that participants proposed were included without any interference.

Thanks to this apparent openness, neither the foreign guests nor many of the invited Cuban intellectuals suspected that an important group of black Cuban intellectuals and artists — among them Rogelio Martínez Furé, Nancy Morejón, Sara Gómez, Pedro Pérez-Sarduy, Nicolás Guillén Landrián, and Walterio Carbonell — had been excluded.

According to the Black Cuban author Carlos Moore, the group had been meeting to discuss the Cuban government’s lack of action against racism, a problem that the revolutionary leaders claimed to have solved with the abolition of racial segregation in the early sixties. In response to a rumor that these intellectuals had drafted a position paper on race and culture in Cuba for the congress, Minister of Education José Llanusa Gobel called them in for a private meeting a couple of days before the event began. After listening to their critiques, Llanusa accused them of being “seditious” and told them that the “revolution” would not allow them to “divide” the Cuban people along racial lines. He explained that the very idea of their “black manifesto” was a provocation for which they would have to recant or face the consequences.

He then barred them from the congress. In addition, each member was subjected to various degrees of punishment. The worst was meted to those unwilling to recant, such as Nicolás Guillén Landrián, the nephew of the national poet laureate and then-president of the Cuban writers and artists union. After the congress, he was repeatedly arrested and later left Cuba as an exile.

Walterio Carbonell, one of the group’s leaders, also refused to recant. A Cuban exponent of Black Power politics, he had originally belonged to the old pro-Moscow Cuban Communist Party. Ironically, he had been expelled from that organization for supporting Fidel Castro’s attack on the Moncada barracks on July 26, 1953. After the revolution, he served as Cuba’s ambassador to the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN). In 1961, he published his Critique: How Cuba’s National Culture Emerged, where he argued that black Cubans had played a major role in the war of independence and the establishment of the republic — a fact that the prerevolutionary white racist culture and institutions had erased. Moreover, he claimed that the black Cuban experience was at the heart of the Cuban Revolution’s radicalism — accordingly, the struggle against racism strengthened rather than weakened the revolution.

Walterio Carbonell

Walterio Carbonell

Thanks to these arguments, Carbonell endured various forms of detention between 1968 and 1974, including compulsory labor. According to Lillian Guerra, after he was released in 1974, he continued to defend his ideas, so he was interned in various psychiatric hospitals and subjected to electroshock and drug therapy for another two to three years. After that, Carbonell spent his remaining years as a little-known researcher at the National Library.

Unlike Carbonell’s cases, the repression case of Cuban poet and journalist Heberto Padilla became well known very quickly. In 1968, Padilla won was awarded the National Union of Writers and Artists of Cuba’s (UNEAC) most prestigious prize for his book of poems Fuera del Juego (Outside the Game). But the government objected to Padilla’s critical, nonconformist spirit and condemned the work, forcing UNEAC to change its line on it as well.

Heberto Padilla

Heberto Padilla

Ostracized and unable to publish in Cuba, Padilla was arrested for daring to read several of his new poems in public and trying to publish a new novel. He was compelled to confess, in Stalinist fashion, his political sins in 1971. This provoked an international scandal, and a large group of well-known intellectuals sympathetic to the Cuban Revolution, such as Jean-Paul Sartre and Julio Cortazar, protested. In response, the regime banned and withdrew from the country’s libraries the works of any Latin American and European intellectual who objected to Padilla’s treatment.

In 1968, the government began using repressive to enforce a monolithic cultural line. This shift created the foundation of what was later called the Quinquenio Gris, the five-year period from 1971 to 1976 in which the Castro regime brutally repressed nonconformist expression. In 1971, the National Congress of Education and Culture viciously attacked gay artists and intellectuals, banned gays from representing Cuba abroad in artistic, political, and diplomatic missions, and branded the Afro-Cuban Abakuá brotherhood a “focus of criminality” and “juvenile delinquency.” Over those five years, the government imposed “parameters” on professionals in the fields of education and culture in order to scrutinize their sexual preferences, religious practices, and relationships with people abroad, among other political and personal issues.

The late Cuban architect Mario Coyula Cowley insisted that the Quinquenio Grishad in fact been the Trinquenio Amargo (the “bitter fifteen years”), because it had really started in the second half of the sixties. The hope that Castro would have supported Czech national self-determination and the upheavals of revolutionary 1968 to chart an independent, more democratic course for the Cuban Revolution was quickly lost.

Cuban security personnel detain a member of the Ladies in White group after their weekly anti-government protest march, in Havana, on September 13, 2015. Human Rights Watch, World Report: Cuba 2016

Cuban security personnel detain a member of the Ladies in White group after their weekly anti-government protest march, in Havana, on September 13, 2015. Human Rights Watch, World Report: Cuba 2016