Fidel Castro recently clarified an allegedly erroneous quotation and stated something to the effect that “Yes the Cuban Model does indeed work”. It would have been difficult for Fidel to do a “Mea Culpa” and agree that half a century of his own management of the Cuban economy had been erroneous and counter-productive.

However, as the grand economic “strategizer” as well as the micro-manager of many issues that captured his attention President Fidel Castro was responsible for a long list of economic blunders. Here is my listing of Fidel’s most serious fiascoes.

Next week I will try and produce a listing of Cuba’s Greatest Achievements under President Castro. Unfortunately I find this more difficult than to identify the failures.

Top Ten Economic Fiascoes

Fiasco # 10 The Instant Industrialization Strategy, 1961-1963:

Fiasco #9 The 10 Million Ton Sugar Harvest Strategy, 1964-1970

Fiasco #8 The “New Man”

Fiasco #7 The “Budgetary System of Finance”

Fiasco #6 The “Revolutionary Offensive” and the Nationalization of Almost Everything

Fiasco #5 Revolucion Energetica

Fiasco #4 Shutting Down Half the Sugar Sector

Fiasvco #3 A Half Century of Monetary Controls and Non-Convertibility

Fiasco #2 Suppression of Workers’ Rights

Fiasco #1 Abolition of Freedom of Expression

Fiasco # 10 The Instant Industrialization Strategy, 1961-1963:

Cuba’s first development strategy, installed by the Castro Government in 1961, called for “Instant Industrialization”, the rapid installation of a wide range of import-substituting industries, such as metallurgy, heavy engineering and machinery, chemical products, transport equipment and even automobile assembly.

The program proved unviable as it was import-intensive, requiring imported machinery and equipment, raw materials, intermediate goods, managerial personnel, and repair and maintenance equipment. Because the sugar sector was ignored, the harvest fell from 6.7 million tons in 1961 to 3.8 in 1963 generating a balance of payments crisis. The end result was that Cuba became more dependent than ever on sugar exports, on imported inputs of many kinds and on a new hegemonic partner, the Soviet Union.

The strategy was aborted in 1964.

Fiasco #9 The 10 Million Ton Sugar Harvest Strategy

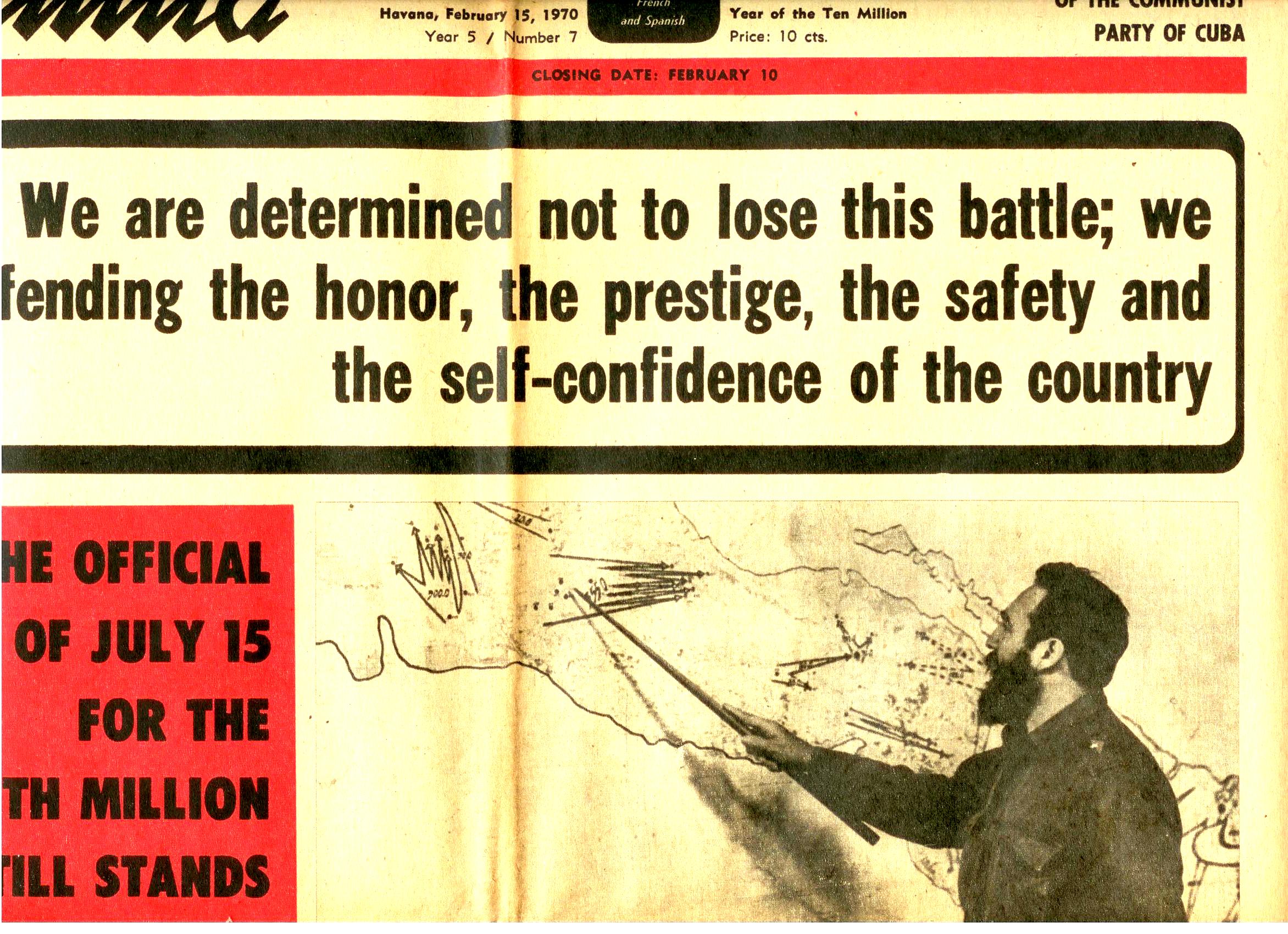

The failure of the “Instant Industrialization” strategy led to an emphasis on sugar production for export with a guaranteed Socialist Bloc market for 5 million tons per year at a price well above the world price – from 1965 to 1970. The over-riding preoccupation became the 10 million ton goal, which according to President Castro was necessary for “defending the honor, the prestige, the safety and self-confidence of the country” (February 9, 1970.)

Fidel seemed happiest when conducting a campaign military style as he did during the effort to produce 10 million tons of sugar.

Fidel seemed happiest when conducting a campaign military style as he did during the effort to produce 10 million tons of sugar.

If it had been implemented in a measured way, a strategy to increase export earnings from sugar would have been reasonable. However, as 1970 approached, the implementation of the 10 million ton target became increasingly forced. Other sectors of the economy were sacrificed as labor, transport capacity, industrial inputs, energy, raw materials and national attention all focused on sugar.

This strategy was aborted in 1970.

Fiasco #8 The “New Man”

In order to mobilize human energies for the 10 million ton harvest a radical “Guevaraist” approach was adopted involving the construction of the so- called “New Man.” The idea behind this was a vision of the Cuban Nation as a guerrilla column marching behind Fidel – somewhat like his marches down the Malecon in 2000-2006 – single-mindedly pursuing a common objective, willingly sacrificing individual interests for the common good and with the esprit de corps, discipline and dedication of an idealized guerrilla band. To promote this revolutionary altruism, the government used public exhortation and political education, “moral incentives” instead of material incentives and proselytizing and enforcement by the Party and other “mass organs” of society.

By 1970, it was apparent that people could not be expected to sacrifice their own and their family’s material well-being and survival for some objective decreed and enforced by the Party. The approach was dropped in 1970.

Fiasco #7 The “Budgetary System of Finance”

In a simultaneous experiment, a so-called “budgetary system of finance” was installed under which enterprises were to operate without financial autonomy and without accounting, neither receiving the revenues from sales of their output nor paying for their inputs with such revenues – somewhat like University Departments.

Without a rational structure of prices, and without knowledge of their true costs or the value of their output, neither enterprises nor the planning authorities could have an idea of the genuine efficiencies of enterprises, of sectors of the economy, or of resource-use anywhere. The result of this was disastrous inefficiency. In President Castro’s words:

“..What is this bottomless pit that swallows up this country’s human resources, the country’s wealth, the material goods that we need so badly? It’s nothing but inefficiency, non-productivity and low productivity.” (Castro, December 7, 1970)

This system was also terminated in 1970.

Fiasco #6 The “Revolutionary Offensive” and the Nationalization of Almost Everything

In the “Revolutionary Offensive” of 1968, Fidel Castro’s government expropriated most of the remaining small enterprise sector on the grounds that it was capitalistic, exploitative, and deformed people’s characters, making them individualistic instead of altruistic “New Men”. The result was true living standards were impaired, product quality, quantity and diversity deteriorated, enterprises were pushed into the underground economy, theft from state sector and illegalities become the norm and citizen’s entrepreneurship was suppressed. This policy was changed in 1993, then contained by tight regulation, licensing and taxation after 1985,.

Again in September 2010, the government of Raul Castro appears ready to expand the small enterprise sector in hopes that it will absorb most of the 500,000 workers to be laid off from the state sector.

Fiasco #5 “Revolucion Energetica”

President Castro’s “Revolucion Energetica” included some valuable elements such as conservation measures, re-investment in the power grid and the installation of back-up generators for important facilities such as health centres. A questionable feature of the plan is the replacement of large-scale thermal-electric plants with numerous small generators dispersed around the island. But the use of the small-scale generators likely constitutes a major error for the following reasons:

- The economies of large scale electricity generation are lost;

- Synchronizing the supply of electricity generated from numerous locations to meet the minute-by-minute changes in electricity demand is complicated and costly;

- Problems and costs of maintaining the numerous dispersed generators are high;

- Logistical control and management costs escalate as the national grid is replaced with regional systems.

- Expensive diesel fuel is used rather than lower cost heavy oil:

- Diesel fuel has to be transported by truck to the generators around the island;

- Investments for the storage of diesel fuel in numerous supply depots are necessary;

- Problems of pilferage of diesel fuel may be significant, and costs of security and protection may be high.

No other country in the world has adopted this method of generating electricity, suggesting that it does not make sense economically.

The energy master-plan also ignores a possible role of the sugar sector in producing ethanol and contributing to energy supplies. The experience of Brazil indicates that at higher petroleum prices, ethanol from sugar cane becomes economically viable. The shut-down of some 70 out of Cuba’s 156 sugar mills in 2003, the moth-balling of another 40 and the contraction of the whole sugar agro-industrial service cluster is also a major loss for electricity generation.

Fiasco #4 Shutting Down Half of the Sugar Sector

In 2002, Castro decided that there was no future in sugar production, a decision prompted by low sugar prices at the time and undoubtedly the continuing difficulties in the sector. He decreed the shut-down of 71 of 156 sugar mills, taking some 33% of areas under sugar cane out of production and displacing about 100,000 workers. It was hoped that land-use would shift to non-sugar crops, that remaining mills would become more productive, and that displaced labour would be reabsorbed elsewhere.

In any case, sugar production has continued to decline which is unfortunate given high prices in recent years. There has not been a shift into ethanol production. The physical plant has continued to deteriorate. The cluster of activities surrounding sugar must be near collapse. The sugar communities are left without an economic base and some face the prospect of becoming ghost towns.

Fiasco #3 A Half Century of Monetary Controls and Non-Convertibility

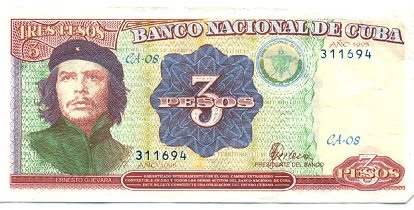

Responsibility for Fiasco #3 is shared in part with Che Guevara, who as President of the Banco Nacianal de Cuba, presided over imposition of monetary controls and implementation of the policies that made Cuba’s peso non-convertible for half a century.

Cuba’s monetary system has been and is a serious obstacle to the freedom of Cuban citizens. Citizens’ incomes have had purchasing power outside the country only when permitted to be exchanged for a foreign convertible currency and then only at a discount for some decades. As is well known, the official exchange rate for Cuban citizens has been in the area of 22 pesos (Moneda Nacional) to US $1.00, so that the purchasing power of the average monthly salary – 415 pesos in 2008 (Oficina Nacional de Estadisticas, 2009, Table 7.4) is about US$20.00.

Fiasco #2 Suppression of Workers’ Rights

Thanks to the regime implanted by President Castro, Cuban workers do not have the right to undertake independent collective bargaining or to strike. Unions are not independent organizations representing worker interests but are official government unions. Independent unions and any attempts to establish them are illegal.

Cuba has signed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and is a member of the International Labor Organization. The basic United Nations Declarations support freedom of association for labor. The International Labor Organization’s Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work includes, as the first fundamental right of labor, “freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining”

The central function of independent labor unions is to provide countervailing power to oligopolistic or monopolistic employers in wage determination and in the setting of the terms and conditions of work. Unions have been successful in western countries in raising wages, improving the equity of income distribution and improving work conditions.

In the Cuban case, workers have confronted a monopolistic employer – the state – that also controls their unions which are in effect “company unions.” By controlling the unions and containing their wage demands, wages have been held down. The absence of independent unions has permitted the government to implement counterproductive economic policies year after year and has muted the urgency of undertaking economic reforms.

Fiasco #1 Abolition of Freedom of Expression

An important requirement for the sustained effectiveness of an economic system is the ability to freely, openly and continuously analyze and criticize its functioning. Open analysis and criticism in a context of free generation and diffusion of information provide a necessary spur for self-correction, exposing illegalities, flawed policies and errors. Free analysis and criticism is vital in order to bring illicit actions to light, to correct errors on the part of all institutions and enterprises as well as policy makers and to help generate improved policy design and implementation. This in turn requires freedom of expression and freedom of association, embedded in an independent press, publications systems and media, independent universities and research institutes, and freely-functioning opposition political parties.

Unfortunately this has been lacking, thanks to the Castro regime. The media and the politicians have largely performed a cheerleader role, unless issues have been opened up for discussion by the President and the Party.

The near-absence of checks and balances on the policy-making machinery of the state also contributes to obscuring over-riding real priorities and to prolonging and amplifying error. The National Assembly is dominated by the Communist Party, meets for very short periods of time – four to six days a year – and has a large work load, so that it is unable to serve as a mechanism for undertaking serious analysis and debate of economic or other matters. The cost for Cuba of this situation over the years has been enormous. It is unfortunate that Cuba lacks the concept and reality of a “Loyal Opposition” within –the electoral system and in civil society. These are vital for economic efficiency, not to mention, of course, for authentic participatory democracy.

NOTE: For additional articles on various aspects of Fidel Castro’s presidency, see:

Fidel Castro: The Cowardice of Autocracy

Cuba’s Achievements under the Presidency of Fidel Castro: The Top Ten

Fidel’s No-Good Very Bad Day

The “FIDEL” Models Never Worked; Soviet and Venezuelan Subsidization Did