Carmelo Mesa-Lago, Catedrático de servicio distinguido emérito en Economía y Estudios Latinoamericanos en la Universidad de Pittsburgh

Pavel Vidal Alejandro, Profesor asociado del Departamento de Economía de la Universidad Javeriana Cali, Colombia

30 de mayo de 2019

Articulo original: LA CRISIS VENEZOLANA Y DE LAS POLÍTICAS DE DONALD TRUMP

Índice

Resumen, Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………….. 2

Introducción ………………………………………………………………………………………………… 3

(1) Antecedentes de la relación económica entre ambos países …………………………. 4

(2) Análisis de la severidad de la crisis económica-social venezolana ……………….. 5

(3) Evolución del comercio exterior cubano con Venezuela……………………………….. 7

(4) Las medidas de Trump contra Venezuela y Cuba ……………………………………….. 14

(5) Los efectos del shock venezolano ……………………………………………………………….. 18

(6) ¿Viene otro Período Especial? …………………………………………………………………….. 22

(7) Posibilidad de que otros países (Rusia o China) sustituyan a Venezuela ……….. 23

(8) ¿Hay alternativas viables para Cuba? ………………………………………………………… 24

(9) Conclusiones……………………………………………………………………………………………… 30

Resumen

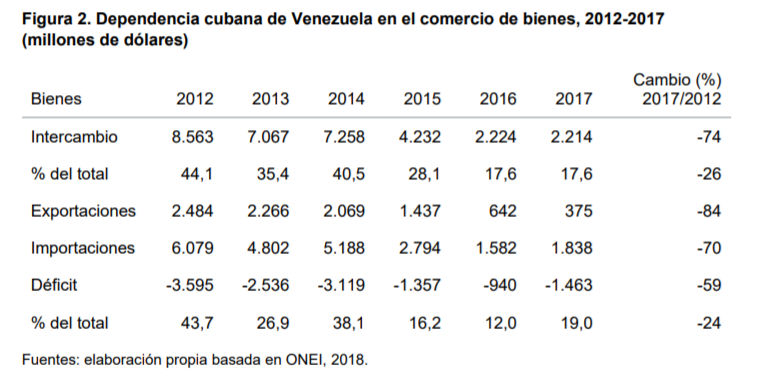

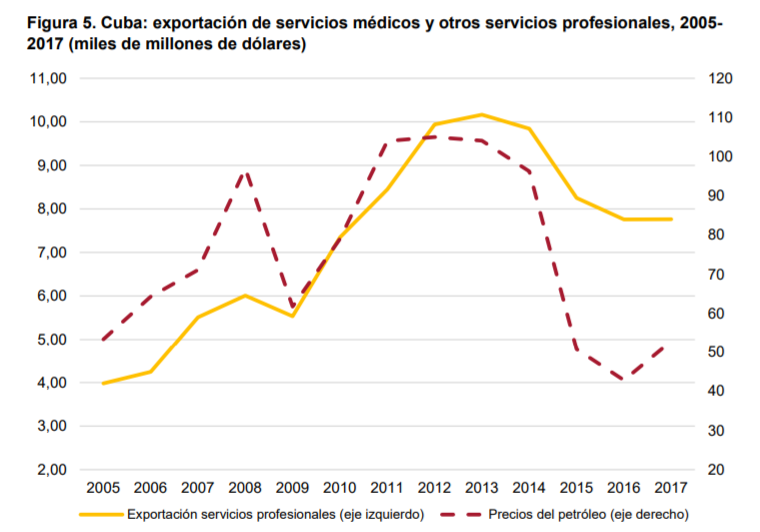

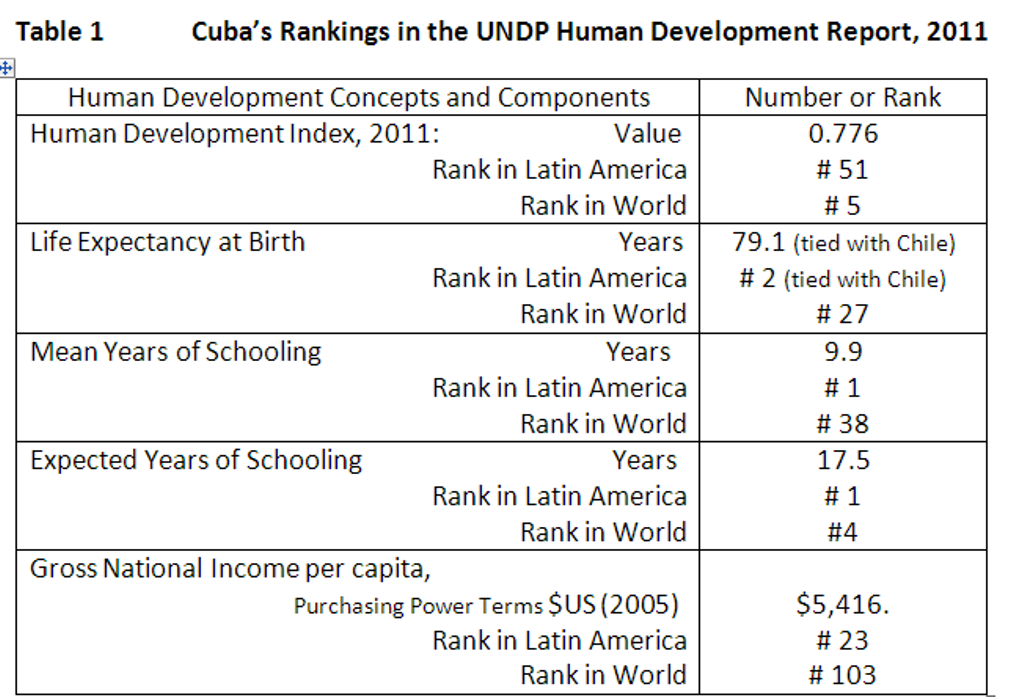

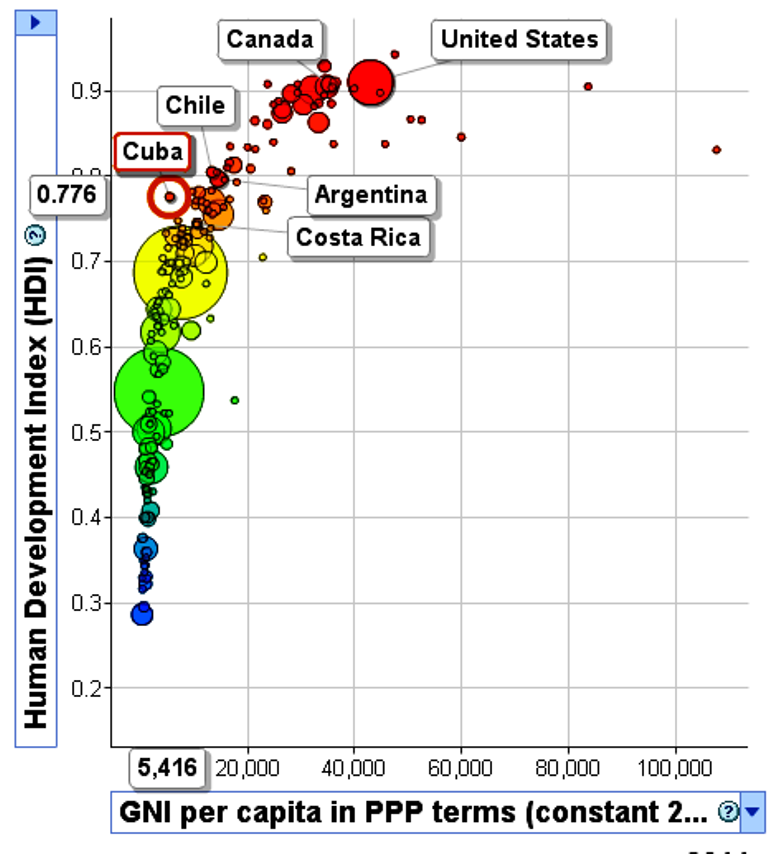

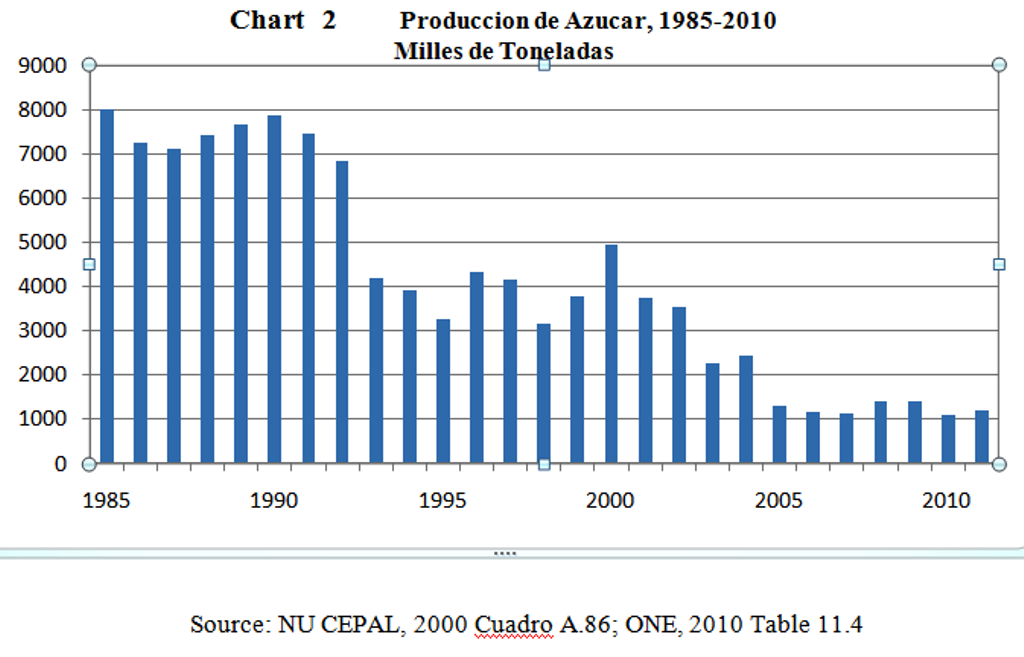

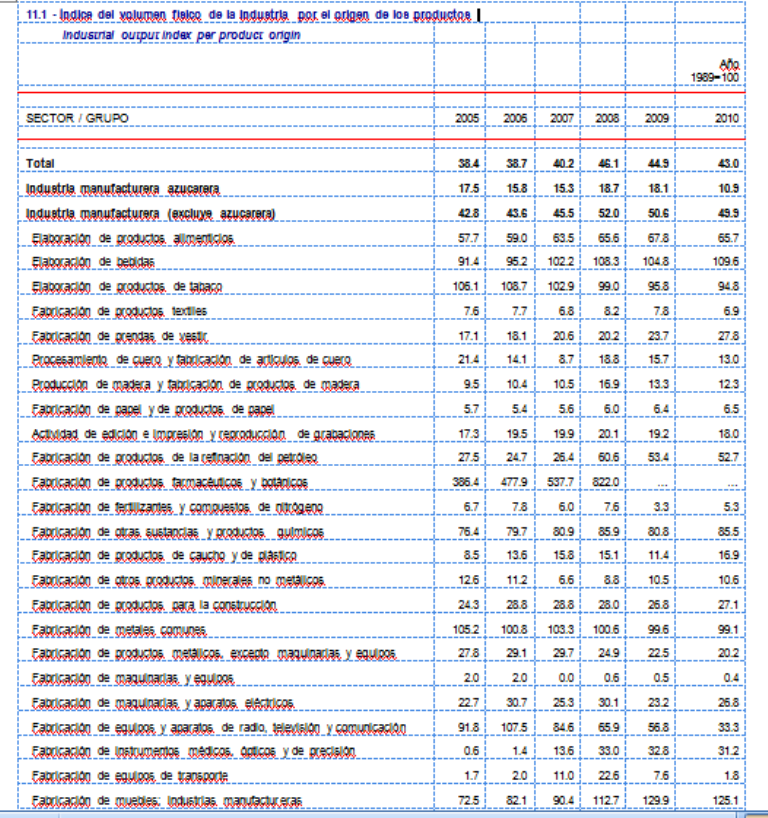

Históricamente, Cuba ha padecido la dependencia económica de otros países, un hecho que continúa después de 60 años de la revolución. La dependencia con la Unión Soviética en 1960-1990 dio lugar al mejor período económico-social en la segunda mitad de los años 80, pero la desaparición del campo socialista fue seguida en los años 90 por la peor crisis desde la Gran Depresión. Este documento de trabajo analiza de manera profunda la dependencia económica cubana de Venezuela en el período 2000- 2019: (1) antecedentes de la relación económica entre ambos países; (2) análisis de la severidad de la crisis venezolana; (3) evolución del comercio exterior cubano con Venezuela; (4) medidas de Donald Trump contra Venezuela y Cuba; (5) efectos del shock venezolano en Cuba; (6) ¿viene otro Período Especial en Cuba?; (7) posibilidad de que otros países (Rusia o China) substituyan a Venezuela; y (8) alternativas viables a la situación. El impacto en la economía cubana de la crisis venezolana y de las políticas de Donald Trump

Abstract

Cuba has historically endured an economic dependence on other nations that continues after 60 years of revolution. Dependence on the Soviet Union in 1960-90 led to its best economic and social situation in the second half of the 1980s, but the disappearance of the socialist world was followed in the 1990s by its worst economic crisis since the Great Depression. This Working Paper analyses Cuba’s economic dependence on Venezuela in 2000-19, as follows: (1) antecedents of the economic relationship between the two countries; (2) evaluation of the severity of Venezuela’s economic-social crisis; (3) evolution of Cuba’s trade relationship with Venezuela; (4) Trump’s measures against Venezuela and Cuba; (5) effects of the Venezuelan shock on Cuba; (6) is another Special Period in the offing?; (7) possibility of another country (Russia or China) replacing Venezuela; and (8) viable alternatives to Cuba.

…………………………………………..

Conclusiones

Este estudio ha aportado evidencia abundante y sólida (respecto a Venezuela) que ratifica la histórica dependencia económica cubana de otra nación y la necesidad de subsidios y ayuda sustanciales para poder subsistir económicamente.

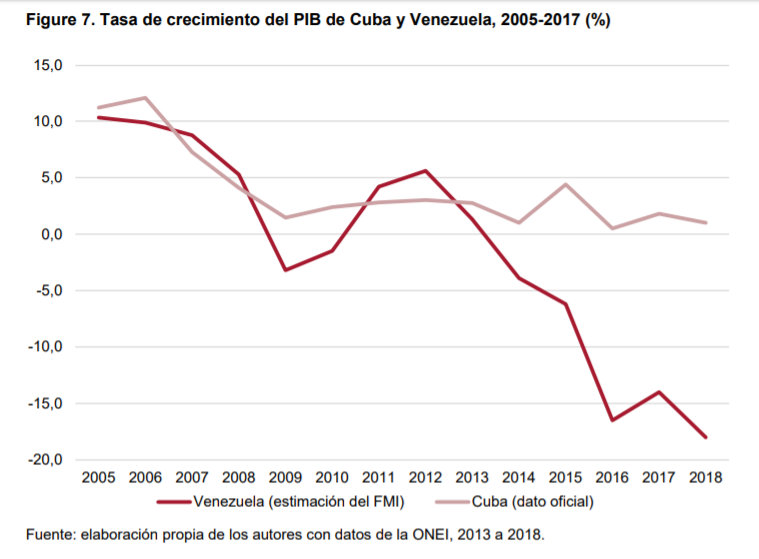

A pesar del gran peso de la beneficiosa relación económica externa, Cuba no ha logrado financiar sus importaciones con sus propias exportaciones. La ayuda externa resulta, al menos por un tiempo, en un crecimiento económico adecuado (en 1985-1989 con la URSS y en 2005-2007 con Venezuela), pero cuando desaparece o entra en crisis el país subsidiador, ocurre una grave crisis en Cuba. La dependencia sobre Venezuela ha sido menor que la relativa con la Unión Soviética y hay además otros factores que podrían atenuar la crisis resultante de la debacle en el primer país; aun así, Cuba ya ha sufrido

El impacto en la economía cubana de la crisis venezolana y de las políticas de Donald Trump Documento de trabajo 9/2019 – 30 de mayo de 2019 – Real Instituto Elcano 31 desde 2012 una pérdida equivalente al 8% de su PIB y una caída del régimen de Maduro agregaría otro 8%. Las medidas de Trump contra Venezuela no han conseguido hasta ahora derrocar el régimen de Maduro y este ha logrado circunscribir algunas de ellas, pero han agravado la crisis en la República Bolivariana creado una situación peliaguda que se agravará en el medio y largo plazo.

Por otra parte, las políticas trumpistas contra Cuba probablemente tendrán un impacto adverso sobre las remesas externas y el turismo (respectivamente la segunda y tercera fuentes de divisas cubanas), mientras que la aplicación del título III de la ley Helms-Burton generaría costes considerables por las demandas interpuestas y un efecto de congelamiento en la inversión futura.

La reacción de la dirigencia cubana frente a la crisis que se agrava ha sido el continuismo, de lo que no ha funcionado por seis décadas; muy poco se dice oficialmente (aunque se destaca por los académicos economistas del patio) sobre la urgente y necesaria profundización de las reformas económicas fallidas de Raúl Castro, a fin de adoptar algunas de las políticas del socialismo de mercado practicado con éxito en China y Vietnam. Para que Cuba pueda encarar la dura crisis que se avecina a corto plazo y conseguir escapar de la dependencia económica externa a largo plazo, esa es la alternativa más viable.