By Andrea Armeni,

Published originally here “CUBA: One step forward” in Emerging Markets, 19/03/2012

After several tough years, the Cuban economy in 2011 started to show signs of recovery. Following a wave of reforms seeking a mild opening of the economy, and renewed, if limited, attention from international partners, some took this as cause for hope that things might be looking up for the island nation. Yet the challenges for the small and isolated enclave of socialism in the Americas remain daunting.

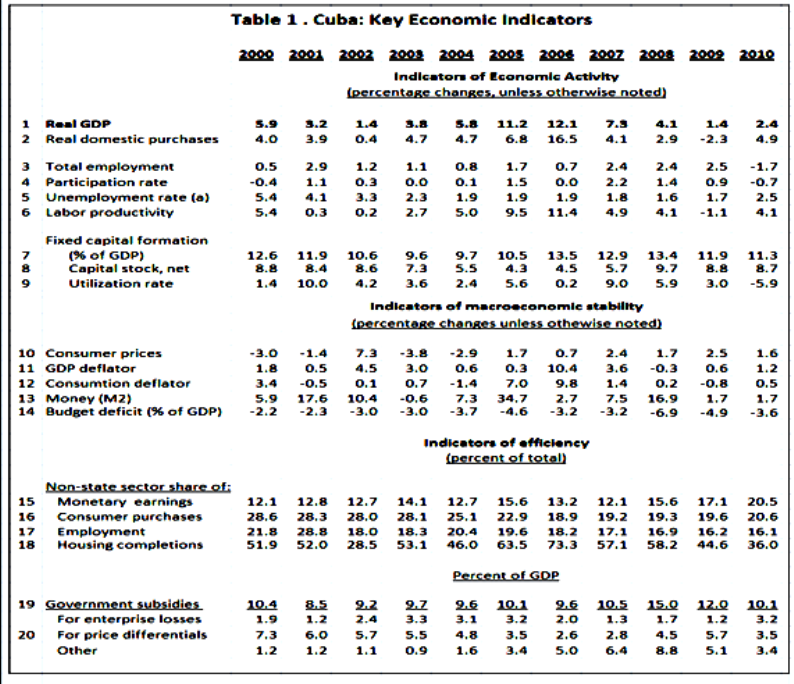

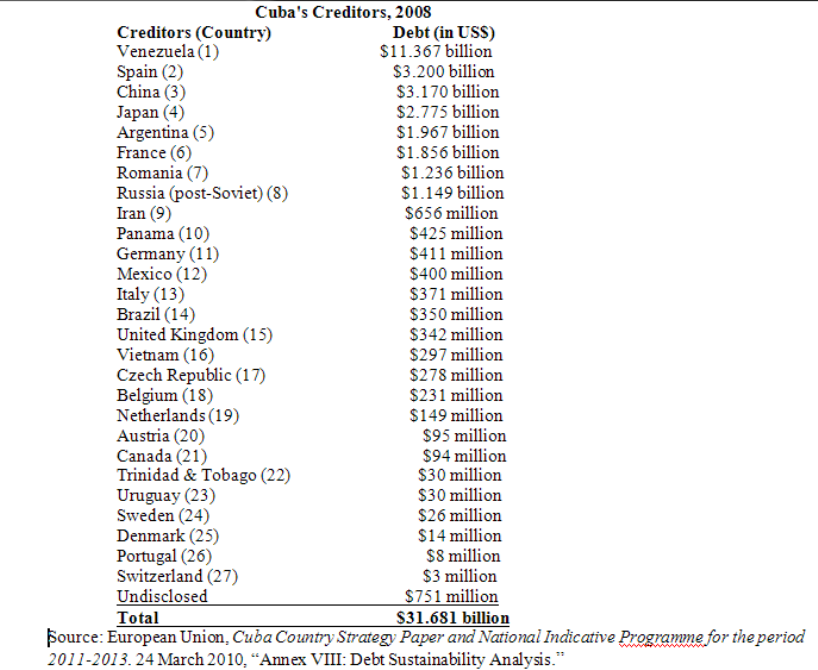

Faced with crippling foreign debt following the liquidity crisis of 2008 and 2009, Cuba found itself in need of a drastic overhaul. Already bare-bone, imports were slashed a further 38%, and government spending was cut back.

But this last crisis finally prompted the state to enact its first series of serious economic reforms in six decades. As Cuba’s outdated economic model is generally considered to be the real reason of its economic ills, any kind of progress in the model is an improvement.

Observers had anticipated that Raúl Castro, after taking over the reins from his brother Fidel in 2006, would herald a period of transition. But early attempts at reform were stymied, and Raúl did not prove to be a stalwart of change. His early criticisms of the Cuban economy did not materialize into effective policy. Moves towards openness and away from the almost absolute control by the state of economic activity didn’t happen.

Real change started to take place in 2011, when Raúl pushed for the long-delayed Sixth Congress to adopt a series of economic action points ranging from a slashing of the bloated state payroll and a sliver of openness to private enterprise, to private ownership of real estate and greater freedoms in agricultural production. The reforms are moving Cuba in the right direction – and, as compared to previous measures, they are concrete measures. According to Armando Linde, former president of the Association for the Study of the Cuban Economy (ASCE), unlike in the past: “the current reforms are not merely to appease possible Castro-fatigue in Cuba. They are doing it because they feel that their model has been exhausted.”

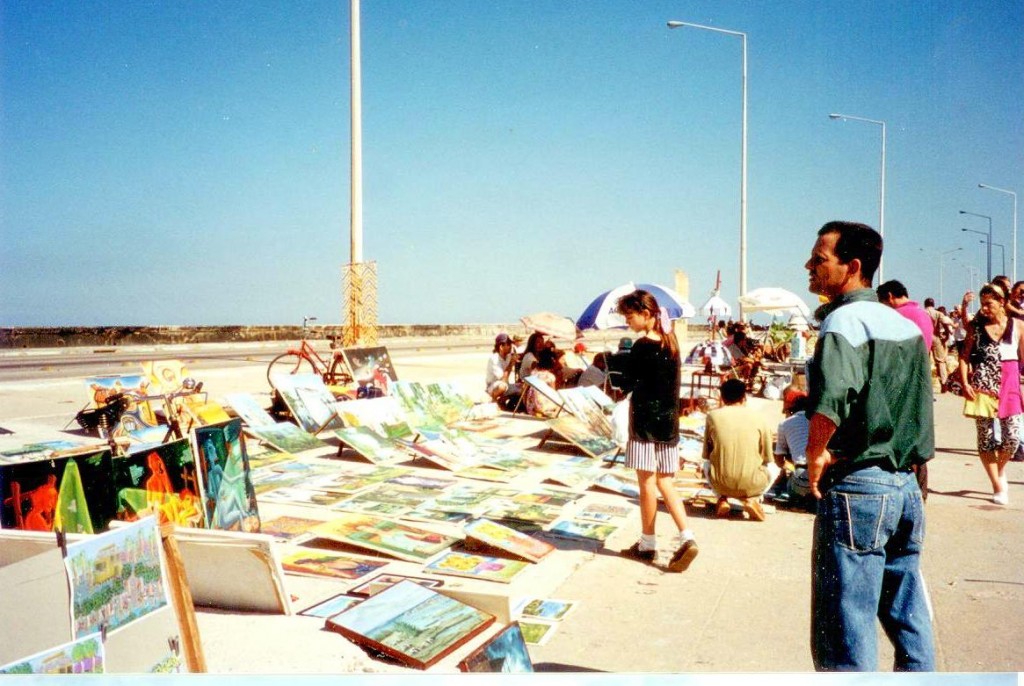

Mercado Artesanal, on the Malecon, Photos by Arrch Ritter, around 2004

Mercado Artesanal, on the Malecon, Photos by Arrch Ritter, around 2004

Richard Feinberg, a non-resident senior fellow of the Brookings Institution and author of a recent major report on Cuba, notes that “the reform process, which is still cautious, is accelerating.”

Richard Feinberg, a non-resident senior fellow of the Brookings Institution and author of a recent major report on Cuba, notes that “the reform process, which is still cautious, is accelerating.”

This positive impression of the state’s intentions is accompanied by a widespread sentiment that the reforms still do not go far – or fast – enough. Others, such as Arch Ritter, a Canadian academic at Carleton University and an expert on the Cuban economy, voice concerns over the feasibility and the implementation of the 300-odd “main lines” of reform.

Cuban economist Oscar Espinosa Chepe, a frequent critic of the state, welcomes the reforms but also notes that the government has already fallen short on its proposed implementation timetable. Omar Everleny, a professor as well as director of the prominent Center for the Study of the Cuban Economy in Havana, sounds a more positive note: “The option given by the government is a good one: a gradual approach, that is to say, every few months a new measure is implemented.” A case in point is the reduction of the state employee rolls: the plan called for the dismissal of half a million workers in the state’s employ by the end of 2011. According to Carmelo Mesa-Lago, a respected scholar of the Cuban economy, only some 100,000 have been dismissed so far. Without the sudden creation of jobs in the private sector, the firing of so many state employees would have resulted in an unemployment rate of 22%, says Mesa-Lago.

With significant limitations on alternative employment for a population used to monopolistic state employment, change has to be gradual.

INITIAL CHANGES

But the resurgence of economic activity is evident, particularly in the capital, and there is little doubt that Cuba’s internal economy has received a positive push by allowing private micro-enterprise. Real GDP growth is expected to reach 2.5% in 2012. But limitations remain in terms of the scarcity of productive inputs, from flour to fertilizer, an uncertain new taxation scheme, and the strangulation of any enterprise that goes beyond a handful of employees.

Agriculture, another sector that has suffered tremendously in the last years, is showing signs of recovery in the official figures. This should be spurred further by easing restrictions on independent agricultural production and sale of farm produce. There is talk of making agricultural credits available as well as providing raw materials, such as seeds and fertilizers, that were previously accessible only to state producers.

But national production across the board remains dismal. Cuba manages its trade deficit in goods only by exporting services, principally in the form of doctors and nurses, to Venezuela and other friendly countries.

Cuba’s dependency on Venezuela creates problems of its own. Venezuela now counts for 40% of Cuba’s hard currency from trade, and its share in Cuba’s total trade deficit has risen to 42%, according to Mesa-Lago. Cuba is still reeling from the impact of the end of Soviet subsidies and many believe that if Venezuela’s policies vis-à-vis Cuba were to change, the island would likely suffer another tremendous crisis. Venezuela’s elections, scheduled for October, have raised the possibility, however slim, that Chávez could be unseated, not least following his diagnosis with cancer. “Cuba is going to be in trouble if there is a change of regime in Venezuela,” says Ritter. “With a regime change in Venezuela, which looks like a possibility, Cuba may lose its massive indirect quasi-subsidization through the purchase of these medical services.”

Nor is there any imminent rescue from other parties in sight. China’s credits are reportedly limited to commercial purchases of Chinese goods (Cuba does not officially publish such figures). Foreign direct investment is still low after the scare from the 2008–09 liquidity crisis, which caused investors to flee as the government froze foreign companies’ bank accounts and limitations emerged on the repatriation of proceeds. At the institutional level, Brazil is a potential partner for Cuba in the coming years. Lula’s seminal visit in 2010 was followed by a three-day visit from president Dilma Rousseff early this year. The economy featured at the core of the discussions, reinforcing Brazil’s presence on the island, with interests that range from a successful tobacco joint venture, Brascuba, to Brazil’s $640 million contribution to the renovation of one of Cuba’s main harbours.

Brazil’s interests in Cuba are far less ideological than those of Venezuela. Brazil’s knowledge and investments in sugar cane and its derivative ethanol could revive Cuba’s sugar industry, for example. But the interest is also geopolitical, as Brazil aims to assert its diplomatic influence over the continent.

The prospect of oil revenues is another reason for hope that Cuba can earn much-needed hard currency. Exploration began earlier this year for offshore oil extraction in Cuba’s waters. While the discovery of drillable reserves would be a godsend to the Cuban economy, any financial rewards would not come for another four or five years. Cuba can’t afford to wait that long on the economic sidelines – the reforms will have to prove effective in spurring internal growth quickly if Cuba is to avert another major crisis.

NOT SO SPLENDID ISOLATION

Beyond all this lies the fact that Cuba is still cut off from all international financial institutions (IFIs). “Cuba can’t be the only country out of some 200 that doesn’t belong to any of these institutions,” says Everleny. “To the extent that Cuba is changing its economy and is establishing better relations with other countries in Latin America, why should Venezuela be a part of these international institutions but not Cuba? Why Ecuador, Bolivia, Nicaragua?” The notion that Cuba should become a member in IFIs is gaining traction. Feinberg’s recent seminal paper, published by the Brookings Institution, analyses the feasibility of Cuba joining the IFIs, and was read with interest in Cuba. Feinberg outlines the complicated interplay between the morass of US legislation surrounding Cuba’s isolation from the rest of the world and the island’s real chances for establishing relations with the IFIs and, perhaps more plausibly, with Andean Development Bank Comunidad Andina de Fomento (CAF), which has already invested beyond its member countries.

“One would imagine that influential CAF shareholders (including Venezuela, Brazil and Argentina) would be supportive, and would agree that the goals of a Cuba fund could be made consistent with overall CAF policies,” says Feinberg’s paper.

For a long time the socialist state scoffed at the idea of dealing with such imperialist institutions as the World Bank and the IMF, but Cuba under Raúl has toned down its rhetoric against the IFIs. A recent visit to Cuba by several World Bank economists – though in their personal capacities – was mentioned positively by several observers.

Everleny, who met officials from the Washington multilaterals visiting Havana, says: “The spirit is to try to initiate an exchange from a technical standpoint – information, publication, access for them to see what is happening in Cuba.”

Officially, the World Bank, the IMF and the IDB will not comment on anything concerning Cuba, but these informal gestures have been welcome – even on the part of the Cuban government. “There has to be a dialogue already, even though officially there has not been a proposal to join any of the IFIs,” says Everleny. “But at the same time – the state has not blocked it either.”

Peter Hakim, president emeritus of the Inter-American Dialogue, echoes the voices that would welcome more involvement by the IFIs in Cuba, even if just at the consultative level. “The World Bank and the IMF have very talented people who know a lot about developing economies; they could be very helpful,” he says, “and even more helpful if they could put some money behind the reform process.”

Linde, the ASCE economist who retired as deputy secretary of the IMF, agrees, but he sees little chance of any significant steps happening quickly. While it is doubtful that any steps towards openness will come from the Obama administration before the 2012 elections, he says: “The Cuban community in the US is becoming more open to a rapprochement with the Castro regime. This younger generation is more amenable to looking ahead rather than looking back to the past.”

But the fact remains that until the US – for whatever reason – demonstrates a willingness to engage with Cuba, there is little prospect for any international action that could do much to improve the lot of the Cuban people. Hakim calls this a “terrible mistake” that has effectively stopped the IFIs from meaningfully approaching Cuba.

One good chance for openness to a dialogue in recognition of Cuba’s reforms should be the Summit of the Americas in April. Despite its lack of participation in the OAS (Organization of American States), Cuba has signalled its willingness to participate in the summit if invited, a position backed by the ALBA (Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas) countries. This is seen by some as a good opportunity for the US and Cuba to greet a new era where the two can sit at the same table.

Uninspiringly, US hardliners such as chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee Ileana Ros-Lehtinen are vehemently opposed to Cuba’s presence at the Colombia Summit: “Allowing the Cuban tyranny to participate would fly in the face of everything the Charter and the OAS is supposed to stand for,” she says.

The isolationist stance has fewer and fewer supporters outside a narrowing cluster of Miami Cubans. The overwhelming majority of non-political observers say the US should recognize the steps taken by Cuba and help push them along. It is 2012, not 1962, after all.