Forbes, Feb 16, 2016

Original Article : CUBA’S FIRST U.S. FACTORY

Horace Clemmons and Saul Berenthal, both 72-year-old retired software engineers, are slated to become the first Americans since 1959 to set up a manufacturing plant in Cuba. Their plan: produce small, easily maintained tractors for use by family farmers. Under new regulations issued by the Obama administration, the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control gave the Paint Rock, AL-based partners the go-ahead last week. Once they get final approval from the Cubans, they anticipate that in early 2017, they’ll start building a factory in a special economic zone set up by the Cuban government in the port city of Mariel. In this condensed and edited interview, Berenthal describes his transition from software entrepreneur to Cuban manufacturing pioneer.

Susan Adams: Tell me about your personal connection to Cuba.

Susan Adams: Tell me about your personal connection to Cuba.

Saul Berenthal: I was born and raised in Cuba. I came to the U.S. in 1960 right after the revolution. First I came and then my parents. My family in Cuba is in the cemetery. But I have lots of friends there and I’ve been traveling back and forth since 2007.

Adams: How did you get the idea to build tractors?

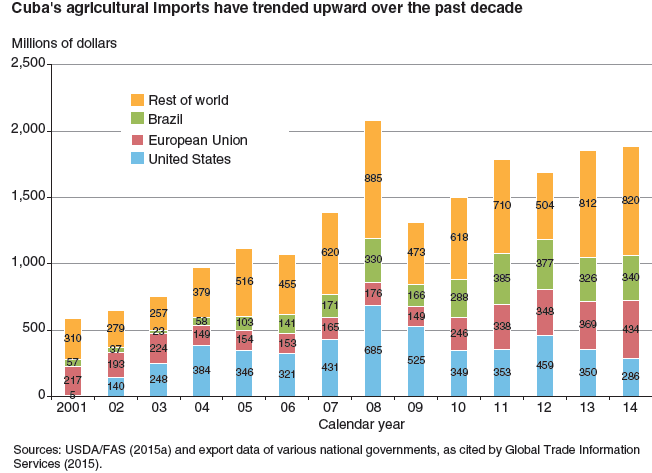

Berenthal: I understood the needs of the Cuban economy. Cuba has to import more than 70% of what people eat. They’re still using oxen to farm the land. Our motivation really is to help the Cuban farmer be more productive.

Adams: But you and Mr. Clemmons are software engineers. How did you know the first thing about farm equipment?

Berenthal: Horace was born and raised on a farm in Alabama. He’s the farming expert and I’m the Cuba expert.

Adams: Just because he was raised on a farm wouldn’t mean he would know how to make tractors.

Berenthal: We hired an engineering company in Alabama that helped us pick up an existing design that was appropriate for what we wanted to do. We brought in state-of-the-art technology and produced the tractors. We have a tractor in Cuba already that’s going to be shown at an agricultural fair in March.

Adams: It sounds like you were motivated less by profit than by a desire to help the Cuban economy and Cuban-American relations.

Berenthal: Yes, our motivation is really to help Cuban farmers be more productive. Through commerce and trade, we can bring Cuban and American people closer together.

Adams: What about making money?

Berenthal: Our business model says we are investing in Cuba and reinvesting any profits we make. We’ll do what we did with our other businesses. We’ll create value and then sell the company.

Adams: What profit margins do you project for your tractors?

Berenthal: We’re aiming for 20%.

Adams: How many tractors do you need to sell before you’re profitable?

Berenthal: We believe we’ll sell 300 tractors in the first year and then we’ll ramp up to 5,000. That includes other light equipment we’ll sell for construction as well. The facility will have the capacity to produce up to 1,000 tractors a year. I think the profitability will come after the first or second year when we start to do production and not just assembly in Cuba.

Adams: But Cuba is plagued by shortages of the most basic products. How will you get tractor parts?

Berenthal: They’re all going to be sourced and shipped from the U.S. The current state of the embargo makes it so we can’t buy parts there. But we think that within the next three years the embargo will be lifted and we’ll be able to source from Cuba, if not sooner.

Adams: Your factory will be in a special economic zone?

Berenthal: It’s called ZED, for Zona Especial de Mariel. It’s built around one of Cuba’s biggest ports and it has a whole bunch of sections dedicated to foreign investment. They provide for a bunch of tax and investment incentives. We’re also taking advantage of Cuba’s commercial treaties with the rest of Latin America, where we’ll be able to ship and provide better pricing than for tractors built in the U.S.

Adams: What kind of tax incentive is Cuba offering?

Berenthal: For the first 10 years we don’t pay any taxes.

Adams: How many local people will you employ?

Berenthal: We’ll start with five and ramp up to 30 within the first year and then probably go up to 300.

Adams: You want to sell the tractors for $8,000-$10,000. How can a Cuban farmer with an ox possibly afford that?

Berenthal: There are a couple of ways. There is financing by the Cuban government and by third countries like Spain, France and the Netherlands. We also count on Cuban-Americans who live in the U.S. who have relatives and friends that run farms. We think they would be happy to contribute to Cubans owning a tractor. We’re also counting on NGOs that help Cuban farmers, like religious groups.

Adams: How much is your initial investment?

Berenthal: We project a $5 million investment and then it will go up to $10 million.

Adams: Where are you getting the money?

Berenthal: It’s private money. We have a couple of investors but we have also sold a couple of companies.

Adams: What did you find when you went to Cuba?

Berenthal: I started meeting with people and I had a lot of contacts in the economics department at the University of Havana. I learned what the Cuban government was proposing to do about readjusting the economy. In 2014, when the opportunity for trade arose, we decided to pursue farming and tractors.

Adams: How difficult was it to get U.S. government approval?

Berenthal: In all honesty it was tedious rather than difficult. We had to wait for the regulations to change so that the proposal we made was covered by the regulations implemented over the last nine months.

Adams: Were you competing with other U.S. companies?

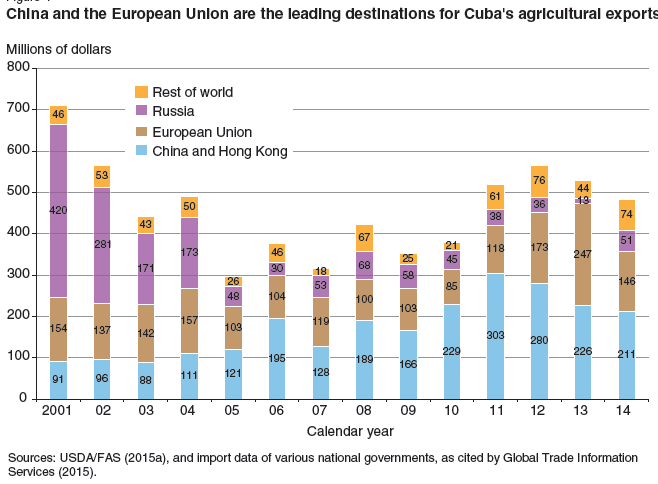

Berenthal: We certainly believe we’re going to compete with the Chinese and Byelorussians, who are the current suppliers of tractors to the Cuban government.

Adams: Where did you get the names for your company, Cleber, and product, Oggun.

Berenthal: Cleber is from our names, Clemmons and Berenthal. It’s clever! Oggun is the name of the deity for iron in the Santeria religion. Santeria is the most popular religion in Cuba. It’s a mixture of Catholic and African religions.

Adams: Do you practice Santeria?

Berenthal: No ma’am. I’m Jewish. We’re called Jewbans