By Emilio Morales and translated by Joseph L. Scarpaci, Miami (The Havana Consulting Group).

Original Article here: The Havana Consulting Group, Joint Ventures

There is a longing in Cuba for the ‘old days’ of the 1990s when there was a successful boom in creating joint-venture companies on the island. Such nostalgia stems from the economic and political crisis in Venezuela, which has lessened the flow of capital from Big-Brother Venezuela.

Joint-venture companies played a key role in helping the Cuban economy recovery in the 1990s when Soviet aid dried up and the so-called Special Period began.

Many of these companies supported the expanding tourist sector and the decriminalization of the U.S. dollar, which became a staple in a dollarized retail market.

This spate of joint ventures sought to develop tourism infrastructure, assist in import substitution, and revive the national economy.

Joint venture companies concentrated mainly in the industrial sector, tourism, food processing, and real estate. Assuming there was a prior agreement with the Cuban counterpart, decisions were usually made by the foreign partner because they had put up the capital and the know-how.

In this stage of the island’s history with joint ventures, foreign companies played a key role training personnel about modern marketing research methods. This was a time when the economic teams of the armed forces launched the so-called ‘business improvement’ (perfeccionamiento empresarial in Spanish) programs.

Upper management teams of these companies learned modern marketing research techniques. Training this echelon of Cuban businessmen and women was a way to ensure loyalty, avoid corruption, and safeguard information.

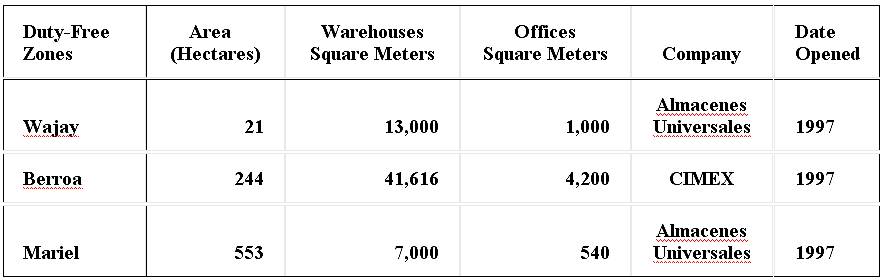

Some $3 billion drove this surge of joint-venture operations and parallel activities in duty-free zones.

Uncertainty lowers the expectations of reforms.

Around 2002, the number of joint ventures and amount of investment capital began declining. Two years later, the government did an about-face and began centralizing the economy once again which, in turn, caused investment to dry up and erode the economic reforms launched in the 1990s.

As a result, some 200 joint-venture operations folded and investment plummeted. The Cuban government took to prioritizing investments with such friendly nations as Venezuela, China and Brazil to fill this investment void, offering private investors slim pickings.

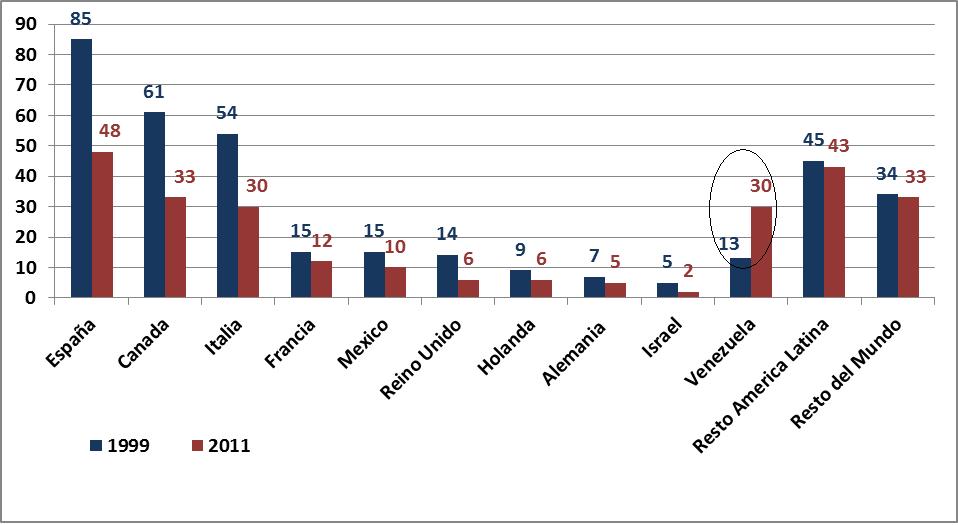

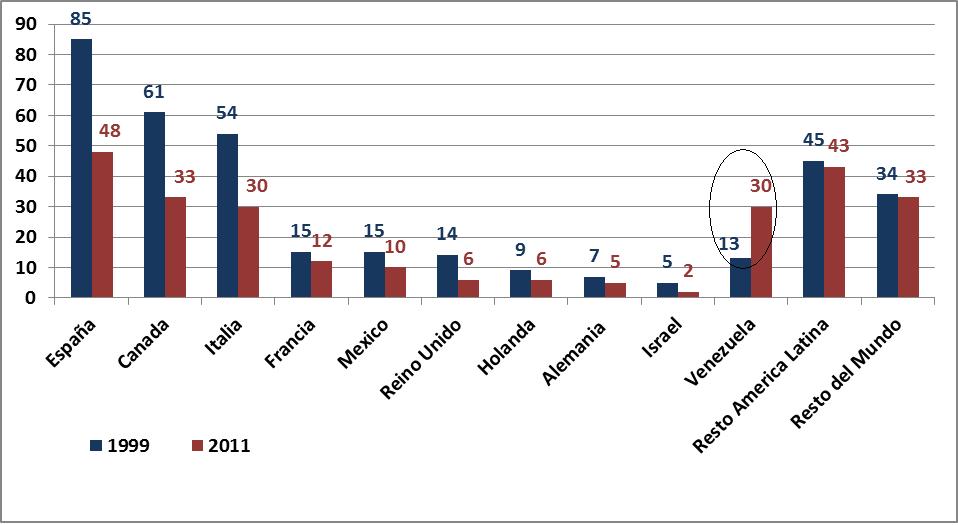

Investment and joint-venture operations dropped off quickly between 1999 and 2011, except in Venezuela, where they shot up from 13 to 30.

Figure 1. Number of Businesses Operating in Foreign Direct Investment, 1999-2001.

Data source: Ministry of Foreign Investment and Collaboration (1999) and the Ministry of Foreign Trade and Foreign Investment (2001, calculated by The Havana Consulting Group.

Those foreign companies that remained in Cuba during this period had to endure, from 2008 to 2010, diminished or no payments that were owed to them by the island’s government (called the corralito, or little corral). Considerable tension resulted, particularly between the Spanish diplomatic corps that pleaded for payment to some 300 Spanish firms who had operations there.

This acute two-year financial crisis stemmed from the island’s lack of liquidity that not only affected the supply of raw materials in the sectors where these foreign firms operated, but decreased inventory in hard-currency retail chains and in tourism. The Cuban government’s failure to make payments led to a further decline in foreign investment as investors got jittery.

Raúl Castro introduced a series of economic reforms called “updating the Cuban economic model” when he came to power. This entailed trying to insert market mechanisms at all levels of the economy with the socialist planning system. Joint ventures were at the center of these measures so that the economy could receive foreign investment. In all instances, the Cuban government maintains at least 51% control of these companies.

From the start of these reforms until October 2013, the bulk of them have tried to expand the private sector and agriculture. However, the pace of foreign investment has not gone as expected because of corruption charges made against some foreign investors residing on the island, and Cuban business representatives of joint-venture firms.

Cuban authorities have detained or jailed several foreign businessmen and high-ranking Cuban officials (including one minister and several vice ministers and Cuban CEOs. They are charged with corruption, bribery, and related crimes. Some have been sentenced up to 10 years while others were acquitted after having spent more than a year in jail while awaiting trial.

Undoubtedly, this anticorruption has proven unattractive to foreign investors because of the uncertainty and insecurity the matter has created.

Searching for investors.

Despite all this, the Cuban government has created a special zone adjacent to the Mariel port, just west of Havana. The Brazilian government has invested $900 million, which the Cuban government hopes will attract foreign investment and give the economy a second chance.

By the looks of things, the Cuban government is moving forward with plans to attract investment. It is noteworthy that Venezuela, its principle political ally and one of two pillars of the Cuban economy, is coping with a deep crisis back home. Still, these strategic actions aim to exceed the results obtained in the 1990s.

Potential gains in joint ventures will likely concentrate in the tourism, agriculture and real-estate sectors.

However, it is unclear whether the traditional business partners already located on the island will play a prominent role. The lack of transparency about the jailing of foreign businessmen and the closing of joint ventures is unattractive to international investors.

If we consider the recent announcement about shifting to a single currency, it is obvious that foreign companies with investments in Cuba take a beating. Government efforts to attract a new wave of investors to the new Mariel port facilities could be impacted adversely because of these proposed monetary changes.

Another weakness is the lack of flexible and attractive foreign investment laws.

This is why the government urgently seeks a new wave of foreign investors. To do that, it has announced that it is reworking its investment laws so that they appeal to the international community. Moreover, for the first time in half a century, these new laws may consider allowing Cubans who reside off the island to invest.

Until now, however, these new laws have not appeared. Until they do, uncertainty grows, the crisis deepens, and the country is losing the glamour and allure it needs to attract new investment.

Hotel Melia Cohiba, Spanish-Cuban Joint Venture

Hotel Melia Cohiba, Spanish-Cuban Joint Venture

Sherritt International Nickel Refinery, Fort Saskatchewan Alberta: Cuban-Canadian Joint Venture in Canada!

Sherritt International Nickel Refinery, Fort Saskatchewan Alberta: Cuban-Canadian Joint Venture in Canada!

Preface

Preface