By Arch Ritter

Does Cuba have an “external debt problem”? Is servicing the debt, that is, paying the interest and amortization, a serious burden for the balance of payments?

Unfortunately, Cuba does not provide sufficient information to analyze this issue clearly. One searches in vain in the documentation of the Oficina Nacional de Estadisticas (ONE) and the web site of the Banco Central de Cuba (BCC) for useful and up-to-date information on debt magnitudes or the cost of servicing the debt. Why is it that all the countries in Africa – excepting Somalia and South Sudan – and all the countries of Latin America can provide up-to-date information on their debts but Cuba can not? [For Africa see the African Economic Outlook, 2012, Table 12 and for Latin America, Naciones Unidas, CEPAL, CEPAL, Naciones Unidas, Balance Preliminarde las Economias de America Latina y el Caribe. 2012]

One can only conclude that Cuba’s debt issue is a matter of “official secrecy”. Presumably it is not due to incompetence in the Central Bank or the Statistical Agency.

Surprisingly, the present lack of timely and detailed information on the external debt is in sharp contrast with the situation under the government of President Fidel Castro in the 1980s. In this period, the BCC published detailed information on the external debt which permitted independent external analysis (See for example A. Ritter, “El problema de la deuda de Cuba en monedas convertibles”; “Cuba’s convertible currency debt problem”, – Revista de la CEPAL; CEPAL Review, 1988, not available in electronic format.)

The most recent number for Cuba’s external “gross debt” provided by the ONE for 2008 was 11.6 billion pesos in Moneda Nacional. This constituted 19.1% of Cuba’s GDP for that year (ONE AEC Table 8.2). These numbers are undoubtedly higher now in 2012 after the 2008-2009 recession.

The total external debt ostensibly amounted to 92.7% of Cuba’s exports of both goods and services in 2008. This does not seem unduly onerous. However, Cuba’s service exports, paid for primarily by the Government of Venezuela in exchange for medical and other services are vulnerable to change if Hugo Chavez were to leave the scene or lose the forthcoming presidential election. These service exports are unsustainable in the long run in any case as countries develop their own medical services.

As a percentage of merchandise exports, Cuba’s gross debt comes in at 325%, a magnitude that is more onerous. Unfortunately lack of relevant information prevents a determination of debt service as a percentage of exports of goods and services or of merchandise exports alone.

But how meaningful are these gross debt figures?

Cuba’s external debt is in foreign currency. Cuba’s domestic GDP is measured in Moneda nacional. What is the reasonable exchange rate for translating Moneda Nacional into a common foreign currency such as the US Dollar? The appropriate exchange rate would not be the official 1.00 CuP = $US 1.00. Nor would the appropriate rate be 24.00 CuC = $US 1.00, which was the exchange rate of the CuP (in Moneda Nacional) to the CuC (or the Convertible Peso.) If it were the latter, then the hard currency debt of 11.6 billion would be 458% of Cuba’s GDP, an amount that would be horrendous. Likely the true weight of the external debt is somewhere the 19.1% of GDP and the astronomical 458% of GDP, but we have little idea exactly where.

Cuba underwent a debt crisis in the late 1980s when it faced a total hard currency debt of $US 5.5 billion. It resolved the problem by first arranging a series of reschedulings. When these did not solve the problem, Cuba suspended negotiations on July 1, 1986, and entered a debt moratorium paying neither interest nor amortization.

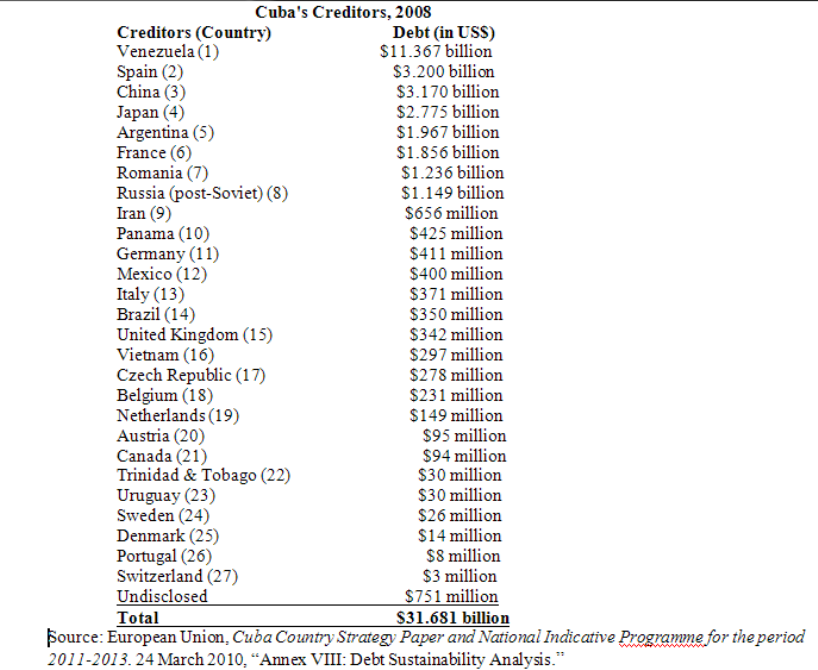

According to a report by the Republic of Cuba-European Union entitled Country Strategy Paper and National Indicative Programme for the period 2011-2013. 24 March, 2010, “Annex VIII: Debt Sustainability Analysis.” Cuba’s creditors, excluding the former Soviet Union, were owed a total of $31.7 billion in 2008. The total volume of debt outstanding now in 2012 is undoubtedly higher than the 2008 figure. Some 20 billion of this was “inactive” or no longer honored by Cuba, but we do not know which debts were no longer active.

Under President Fidel Castro and perhaps Raul Castro as well, Cuba has played an interesting and remunerative game, making economic friends with a succession of suitors, obtaining trade, official and bank credits from its partners, and then reneging on the debt. The most dramatic example was of course the former Soviet Union which extended credits amounting to around 20 billion transferable rubles, or some $US(1988) 28 billion. This debt plus other debts with the countries of the Soviet Bloc is not acknowledged by Cuba will never be repaid.

Under President Fidel Castro and perhaps Raul Castro as well, Cuba has played an interesting and remunerative game, making economic friends with a succession of suitors, obtaining trade, official and bank credits from its partners, and then reneging on the debt. The most dramatic example was of course the former Soviet Union which extended credits amounting to around 20 billion transferable rubles, or some $US(1988) 28 billion. This debt plus other debts with the countries of the Soviet Bloc is not acknowledged by Cuba will never be repaid.

More recently, Venezuela, China and Iran have been the favored economic partners with Cuba extending credit to promote their exports. Will they also be “stood up”, “let down” or “dumped” by Cuba when the credits run out?

Certainly when Chavez leaves the scene and when Venezuela decides to end its special relationship with Cuba, Cuba will likely declare a moratorium. Are there additional suitors who are willing to enter a special economic relationship with Cuba and provide new credit lines? I can no longer see a waiting list of suitors. However, there may well some ready to succumb to the charms of Cuba, its diplomats and its trade negotiators. Perhaps Brazil is next in line!