-

Tags

Agriculture Art Markets Association for the Study of the Cuban Economy Baseball Black Market Book Book Review Bseball Buena Vista Social Club Business Cartography Castro Dynasty CELAC Central Planning Che Guevara Civil Liberties Civil Society Comedy Communications Communist Party of Cuba Comparative Experience Compensation issue Confiscations Constitution Cooperatives Corona Virus Corruption Covid 19 criptomoneda Cuba Cuba-Africa Relations Cuba-Brazil Relations Cuba-Canada Relations Cuba-Caribbeab Relations Cuba-China Relations Cuba-European Union Relations Cuba-Haiti Relations Cuba-Russia Relations Cuba-Soviet Relations Cuba-Spain Relations Cuba-Venezuela Relations Cuban-Americans Cuban Adjustment Act Cuban Diaspora Cuenta Cuenta-Propistas Cultural Policy Culture Currency Reform Daily Life 2012 Debt Issue Defense and Security Issues Democracy Demography Development Assistance Development Strategy Digital Library Diplomacy Dissidents Document Archive EBOLA Econmic Institutions Economic Growth Economic History Economic Illegalities Economic Institutions Economic Melt-Down Economic Model 2016 Economic Prospects Economic Recovery Economic Reform Economic Reforms Economic Self-Correction Education Eighth Party Congress Electricity Embar Embargo Emig Emigration Employment Energy Enterprise Management Entrepreneurship Environment Eusebio Leal Exchange Rate Policy Export Processing Zone Exports Expropriated Properties External Debt Fidel Fidel Castro Finance Fiscal Policy Foreign Foreign Exchange Earnings Foreign Exchange Earninigs Foreign Investmenr Foreign Investment Foreign Trade Freedom of Assembly Freedom of Expression Freedom of Movement Gender Issues Genera General Economic Analyses General Economic Performance Guantanamo Havana Health Hel Helms-Burton Bill History Housing Hugo Chavez Human Development Human Rights Humor Hurricane Hurricane IRMA Illegalities Income Distribution Industry Inequality Inflation Information Technology Infrastructure Inlation Innovation International Financial System International Relations Internet Interview Joe BIden Joint Ventures Journalism Labor Rights Labour Issues Lineamientos Literature Living Standards Luis Alberto López-Calleja Macroeconomy Manufacturing Sector Maps Marabu Mariel Market Socialism Media Medical System Microfinance Migration Miguel Diaz-Canel Military Mineral Sector MIning Missile Cisis 1962 Monetary System Music Narcotics Policy National Accounts National Assembly National Development Plan 2016-2030 New York Times Nickel Industry Nicolas Maduro Normalization North Korea - Cuba Relations OAS Summit Obam Obama Oligopoly Omar Everleny Perez Opposition Organization of American States Oscar Espinosa Chepe Paladares Panama Papers Pandemic Pensions Petroleum PHOTOGRAPHS polit Politic Political System Politics Poll Pope Francis Population Poverty Ine President President Raul Castro Private Sector Property Claims Property Market Protest Protests Public Finance Putin Race Raul Castro Real Estate Market Rectification Process Regional Development Regional Integration Regulation Relations with Latin American Religion Remittances Resources Revolutionary Offensive 1968 Rum Self Self-Employment Services Seventh Party Congress Sherritt Sherritt International Simon Joel Sixth Party Congress Small Small Enterprise Social Social Indicators Socially Responsible Enterprise Social Security Soviet Subsidization Special Period Sports State Enterprise Structural Adjustment Structural Change Succession Sugar Sector tax Taxation The Arts Tiendas Recaudadoras De Divisas Tobacco Tourism Trade Trade Strategy Transportation Trum Trump Ukraine Underg Underground Economy UNDP HDR 2010 UNDP HDR 2011 Unemployment Universities Urbanization US-Cuba Normalization US-Cuba Relations Venezuela Viet Nam Wage Levels Water Resouirces Yoani Sanchez ZIKA VirusPrimary Source Materials

Authors

- . Gioioso Richard N

- 14YMEDIO

- Ablonczy Diane

- Acosta Gonzalez Eliane

- Adams David

- Adams Susan

- Agence France-Presse

- Agencias Madrid

- Aja Díaz Antonio

- Alarcón Ricardo

- Albizu-Campos Espiñeira Juan Carlos

- Almeida J. J.

- Alvarez Aldo

- Alvarez José

- Alzugaray Carlos

- Amnesty International

- Anaya Cruz Betsy

- Anderson John Lee

- Aníbal

- Anio-Badia Rolando

- Arch

- Armeni Andrea

- Armstron

- Armstrong Fulton

- ARTnews

- ASCE

- Associated Press

- Augustin Ed

- Azel José

- Bain Mervyn J.

- Baranyi Stephen

- Barbería Lorena

- Bardach Ann Louise

- Barral Fernando

- Barrera Rodríguez Seida

- Barreto Humberto

- Batista Carlos

- Bayo Fornieles Francesc

- BBC

- Becker Hilary

- Becque Elien Blue

- Belt Juan A. B.

- Benjamin-Alvarado Jonathan

- Benzi Daniele

- Betancourt Rafael

- Betancourt Roger

- Blanco Juan Antonio

- Bobes Velia Cecilia

- Borjas George J.

- Brennan David

- Brenner Philip

- Brookings Institution

- Brown Scott

- Brundenius Claes

- Bu Jesus V.

- Buigas Daniel

- Burnett Victoria

- Bye

- Bye Vegard

- Café Fuerte

- CaféFuerte

- Cairncross John

- Campbell Morgan

- Campos Carlos Oliva

- Campos Pedro

- Caruso-Cabrera Michelle

- Casey Michael

- Castañeda Rolando H.

- Castellano Dimas

- CASTILLO SANTANA MARIO G.

- Castro Fidel

- Castro Ramphis

- Castro Raúl

- Castro Teresa Garcia

- Catá Backer Larry

- Cave Damien

- Celaya Miriam

- Centeno Ramón I.

- Center for Democracy in the Americas’ Cuba Program

- Center for Latin American Studies at American University

- Centro de Estudios sobre la Economia Cubana

- César Guanche Julio

- CÉSPEDES GARCÍA-MENOCAL MONSEÑOR CARLOS MANUEL DE.

- Chaguace daArmando

- CHAGUACEDA ARMANDO.

- Chase Michelle

- Chepe

- Chepe Oscar

- Christian Solidarity Worldwide

- CiberCuba

- Community of Democracies

- Cordoba Jose de

- Crahan Margaret E.

- Cuba Central Team

- Cuba Standard

- Cuba Study Group

- Cuban Research Institute

- D´ÁNGELO OVIDIO.

- DACAL ARIEL.

- Dade Carlo

- de Aragon Uva

- de Céspedes Monseñor Carlos Manuel

- De la Cruz Ochoa Ramón

- De la Fuente Alejandro

- de la Torre Augusto

- De Miranda Parrondo

- del Carmen Zavala María

- DFAIT Canada

- DIARIO DE CUBA

- Diaz Fernandez Ileana

- Diaz Ileana

- Diaz Moreno

- Diaz Moreno Rogelio Manuel

- Díaz Oniel

- Díaz Torres Isbel

- Díaz Vázquez Julio

- Díaz-Briquets Sergio

- Dilla Alfonso Haroldo

- Diversent Laritza

- Domínguez Jorge I

- DOMÍNGUEZ JORGE I.

- Dore Elizabeth

- Duany Jorge

- Duffy Andrew

- Echavarria Oscar A.

- Echevarría León Dayma

- Economist Intelligence Unit

- Eduardo Perera Gómez Eduardo

- EFE

- Eire Carlos

- Ellsworth Brian

- Environmental Defense Fund

- Erikson Daniel P

- Erisman Michael

- Escobar Reinaldo

- Espacio Laical

- Espino María Dolores

- Farber Samuel

- Faya Ana Julia

- Feinberg Richard E.

- Feinsilver Julie M.

- FERNÁNDEZ ESTRADA JULIO ANTONIO.

- Fernandez Tabio Luis Rene

- Field Alan M.

- Florida International University

- Font Mauricio

- FOWLER VÍCTOR.

- Frank Mark

- Franks Jeff

- Fulton

- Fusco Coco

- Gabilondo Jose

- Gabriele Alberto

- Gálvez Karina

- Gámez Torre Nora

- Gámez Torres Nora

- Garcia Alvarez Anicia

- Garcia Anicia

- Garcia Anne-Marie

- Garcia Cardiff

- Garcia Enrique

- Garrett Laurie

- Gazeta Oficial

- Globe and Mail

- Gómez Manzano Rene

- González Ivet

- González Lenier

- González Mederos Lenier

- Gonzalez Roberto M

- González Roberto Veiga

- González-Corzo Mario A.

- Gonzalez-Cueto Aleida

- Gorney Cynthia

- Granma

- Grant Tavia

- Gratius Susanne

- Grenier

- Grenier Guillermo J.

- Grenier Yvon

- Grogg Patricia

- GUANCHE ZALDÍVAR JULIO CÉSAR.

- Gutiérrez Castillo Orlando

- Hagelburg G. B.

- Hakim Peter

- Hansel Frank-Christian

- Hansing Katrin

- Hare Paul Webster

- Hargreaves Clare

- Havana Times

- Haven Paul

- Hearn Adrian H.

- Henk

- Henken Ted

- Hernández Rafael

- Hernández Sánchez Lisbán

- Hernández-Catá Ernesto

- Herrero Ricardo

- Hershberg Eric

- Hirschfeld Katherine

- Human Rights Watch

- Íñigues Luisa

- International Republican Institute

- Ize Alain

- Jiménez Guethón Reynaldo

- JIMÉNEZ MARGUERITE ROSE

- Justo Orlando

- Karina

- Kergin Michael

- Kirk Emily J.

- Kirk John

- Klepak Hal

- Koring Paul

- Kornbluh Peter

- Kraul Chris

- Kunzmann Marcel

- Lafitta Osmar

- Lai Ong

- Latell Brian

- Legler Thomas

- Leiva Miriam

- Leogrande

- LeoGrande William M.

- León-Manríquez José Luis

- Liu Weiguang

- Lo Brutto Giuseppe

- Lockhart Melissa

- Lopez-Levi Arturo

- López-Levy Arturo

- Lozada Carlos

- Luis Luis R.

- Lutjens Sheryl

- Luxner Larry

- Mack Arien

- Mao Xianglin

- Marino Mallorie E.

- MÁRQUEZ HIDALGO ORLANDO.

- Márquez Orlando

- Marrón González

- Martinez Alexandra

- Martínez Reinosa Milagros

- Martínez-Fernández Luis

- Maybarduk Gary

- Mayra Espina

- McKenna Barrie

- McKenna Peter

- McKercher Asa

- McNeil Calum

- Meacham Carl

- Mejia Jairo

- Mesa-Lago Carmelo

- Messina Bill

- Milne Seumus

- Ministerio de Justicia

- Ministerio de Salud

- Miroff Nick

- Monreal González Pedro

- Montaner Carlos Alberto

- Morales Domínguez Esteban

- Morales Emilio

- Morales Esteban

- Morales Rosendo

- Morris Emily

- Mujal-Leon Eusebio

- MULET CONCEPCION YAILENIS

- Muse Robert

- Nagy Piroska Mohácsi

- Naím Moisés

- National Geographic

- New York Times

- Nicol Heather

- Nova González Armando

- Offman Craig

- Oficina Nacional de Estadisticas y Informacion

- Omar

- OnCubaNews

- Orro Roberto

- Orsi Peter

- Oscar

- Pacheco Amaury

- Padrón Cueto Claudia

- Padura Fuentes Leonardo

- Pajon David

- Parker Emily

- Partido Comunista de Cuba

- Partlow Joshua

- Pedraza Sylvia

- Perera Gómez Eduardo

- Pérez Lorenzo

- Pérez Lorenzo L.

- Pérez Omar Everleny

- Pérez-Liñán

- Pérez-López Jorge

- Pérez-Stable Marifeli

- PESTANO ALEXIS.

- Peters Phil

- Petras James

- Piccone Ted

- Piñeiro Harnecker Camila

- Pinero Harnecker Camila

- Piñón Jorge R.

- Politics

- Pons Perez Saira

- Posner Michael

- Powell Naomi

- Pravda

- President Obama

- Press larry

- Prevost Gary

- PRIETO SAMSÓNOV DMITRI.

- puj

- Pujol Joaquín P.

- Pumar

- Pumar Enrique S.

- Quartz

- Radio Netherlands Worldwide

- Rathbone Jphn Paul

- Ravsberg Fernando

- Reporters Without Borders

- Reuters

- Ricardo Ramírez Jorge

- Ritter

- Ritter Arch

- Robinson Circles

- Rodriguez Andrea

- Rodríguez José Luis

- Rodriguez Rodriguez Raul

- Rodriquez Jose Luis

- Rogelio Manuel

- Rohrlich Justin

- Rojas Janet

- Rojas Rafael

- Romero Antonio F.

- Romero Carlos A.

- Romero Vidal

- Romeu Jorge Luis

- Romeu Rafael

- Ross Oakland

- Sagebien Julia

- Saladrigas Carlos

- Salazar Maria Elvira

- Sánchez Jorge Mario

- Sánchez Juan Tomas

- Sánchez Yoani

- Sanders Ronald

- Sanguinetty Jorge A.

- Santiago Fabiola

- Scarpacci Joseph L.

- Scheye Rlaine

- Seiglie Carlos

- Sher Julian

- Smith Anthony

- Sofía

- Spadoni Paolo

- Srone Richard

- Stevens Sarah

- Strauss Michael J.

- Stusser Rodolfo J.

- Sullivan Mark P.

- Svejyar Jan

- Tamayo Juan

- The Economist

- Theiman Louis

- Thiemann Louis

- Toro Francisco

- Toronto Star

- Torres Perez Ricardo

- Torres Ricardo

- Tønnessen-Krokan Borghild

- Travieso-Dias Matias F.

- Trejos Alberto

- Triana Cordovi Juan

- Triana Juan

- Triff

- Triff Soren

- Trotta Daniel

- Tummino Alana

- UN ECLAC

- United States Department of Agriculture

- US Department of Agriculture

- US Department of the Treasury

- US International Trade Commission

- US Treasury

- USÓN VÍCTOR

- Valdés Dagoberto

- Vazquez Jose

- Vega Veronica

- Veiga González Roberto

- Vera Rojas

- Verma Sonia

- Vidal Alejandro Pavel

- Vidal José Ramón

- Vignoli Gabriel

- Villalobos Joaquin

- Vuotto Mirta

- Warren Cristina

- Weinreb Amelia

- Weissenstein Michael

- Wells Cheney

- Werlau Maria C.

- Werner

- Werner Johannes

- West-Durán Alan

- Whitefield Mimi

- Whitfield Esther

- WOLA

- Wolfe Andy

- Woolley Frances

- Wylie lana

- Yaffe Helen

- YAKABUSKI KONRAD

- Yoani

- Zamora Antonio R.

Websites and Blogs from Cuba

- OnCubaNews

- Diario de Cuba (DDC)

- Las Damas de Blanco

- Lunes de Post-Revolucion

- 14 y medio

- Espacio Laical: CONSEJO ARQUIDIOCESANO DE LAICOS DE LA HABANA

- Granma, Órgano oficial del Comité Central del Partido Comunista de Cuba.

- Pedro Monreal, el estado como tal

- Havana Times

- La Joven Cuba

- Desde aquí / Reinaldo Escobar

- Translating Cuba, Translations of website postings from Cuba, mainly from 14 y Medio

- La Joven Cuba

Websites and Blogs on Cuba

Web Sites and Blogs on the Cuban Economy

- Pedro Monreal, el estado como tal

- ASCE Annual Proceedings

- Republica de Cuba: Oficina Nacional de Estadisticas

- Revista Temas de Economía Mundial. 2011 – 2020.

- Centro de Estudios de la Economía Cubana (CEEC)

- 14 y medio

- Association for the Study of the Cuban Economy (ASCE)

- Revista de la Facultad de Economía de la Universidad de La Habana.

Economics Websites: General

Featured

Recent Comments

- Erika Hagelberg on G. B. Hagelberg, Analyst and Friend of Cuba. His Last Work: ¨Cuban Agriculture: Limping Reforms, Lame Results”

- botas de mulher on ‘NOW IT WILL ONLY GET WORSE’: CUBA GRAPPLES WITH IMPACT OF UKRAINE WAR

- Roberto Bonachea Entrialgo on Esteban Morales Domínguez, “FRENTE A LOS RETOS DEL COLOR COMO PARTE DEL DEBATE POR EL SOCIALISMO” and Commentary by Juan Tamayo

- Merna Gill on THE CUBAN EMBARGO HAS FAILED

- Vahe Demirjian on THE UNITED STATES AND CUBA: A NEW POLICY OF ENGAGEMENT

- Arch Ritter on THE 2020 FIU CUBA POLL: BEHIND THE PARTISAN NOISE, A MAJORITY OF CUBAN-AMERICANS SUPPORT ENGAGEMENT POLICY.

- Vahe David Demirjian on THE 2020 FIU CUBA POLL: BEHIND THE PARTISAN NOISE, A MAJORITY OF CUBAN-AMERICANS SUPPORT ENGAGEMENT POLICY.

- Diane Duffy on CANADIAN RETIREE TURNING OUT HANDMADE BASEBALL BATS FOR CUBA

- Alexis Aguilera-Borges on Jump-Starting the Introduction of Conventional Western Economics in Cuba

- Lechner Rodríguez Aguilar on Recuperation and Development of the Bahi ́a de la Habana

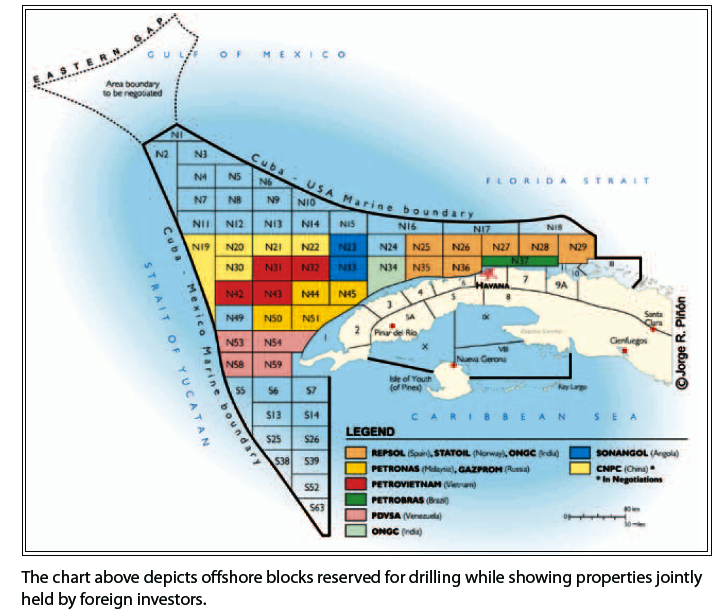

Cuba’s Offshore Petroelum Exploration and U.S. Policy

| POLITICO: Cuba drilling next hurdle for U.S. By: Darren Goode (Courtesy of Jorge R. Piñón) September 27, 2011 10:38 PM EDT |

| The White House must crisscross complex political and policy waters as it faces the impending reality of oil drilling off Cuba a mere 60 miles from the Florida Keys.

“It’s just like firing a shotgun in a crystal store,” said Jorge Piñón, a visiting fellow with the Florida International University Latin American and Caribbean Center’s Cuban Research Institute. “You’re going to break something eventually.” That presents multiple challenges for the Obama administration, which is tasked with protecting the U.S. coastline and waters if a catastrophe begins off Cuba. “I think there is a lot of a tendency to hold the breath and hope it doesn’t happen,” said Lee Hunt, president of the International Association of Drilling Contractors. “I can assure you that inaction and lack of leadership against a potential disaster would be this administration’s Katrina.” Administration officials have already upgraded drilling standards for operations off the U.S. coast and have established a partnership with Mexico to set higher bilateral standards in the Gulf of Mexico since last year’s historic spill. And Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation and Enforcement Director Michael Bromwich said last week that “the issue of drilling offshore Cuba has been on our screen for many months.” “I can say that this issue has been focused on and discussed in very high levels of the government,” Bromwich said. The Spanish company Repsol is expected by January to begin drilling a deepwater exploratory oil well off Cuba in waters about 60 miles south of Key West and slightly deeper than BP’s doomed Macondo exploration well. Other exploratory wells from the same Chinese-built semi-submersible rig owned by the Italian company Saipem would follow in subsequent months — involving companies such as Russia’s Gazprom. “Politicians don’t like to take the risk with Cuba unless they see a clear positive payback of some sort,” said Bill Reilly, a former EPA administrator under President George H.W. Bush. “Now that we see the rig approaching Cuban waters, the political calculus will change.” Reilly — who co-chaired a bipartisan commission that investigated last year’s Gulf spill — and Hunt were among a group granted permission by the administration to trek to Havana in early September to talk to senior Cuban officials in the absence of direct talks between the two governments. “The message was drilling in deepwater is a highly challenging, risky, technologically complex job, and the lessons of Macondo show that even very experienced companies and very practiced regulators can get it wrong,” Reilly said. Hunt, who was following up on a trip he made to Cuba last year, said the biggest difference between the two trips is the Cuban government “had taken a great deal more investigation” into safety and other protocols adopted by the U.S. and Mexico. “In a way, I would say in 2010 they had a very solid regulatory plan. In 2011, they had a fairly sophisticated regulatory plan,” Hunt said. “I don’t have too many concerns about their ability to drill safely.” Reilly and former Royal Dutch Shell Vice President Richard Sears, the chief technical adviser to the president’s spill commission, were in Cuba to explain the commission’s recommendations and findings. “Turned out they knew the oil spill commission’s recommendations cold,” said Reilly, who later briefed Bromwich and White House officials about the trip. “That was kind of surprising and reassuring. They are aware they have very serious challenges, as any country that’s never done this before should have.” But for many, the main concern is that U.S. equipment and personnel would not be ready to act quickly enough to respond to a spill. “What’s in place from the U.S. side to respond and basically prepare for a worst case or really a spill of any kind?” asked Dan Whittle, director of the Environmental Defense Fund’s Cuba program, who was also on this month’s five-day trip to Havana. Because of the decades-old U.S. embargo against Cuba, Hunt said, many resources would have to be shipped from as far away as the North Sea, the United Kingdom, North Africa or Asia. Reilly, Hunt and Whittle are among those asking the Obama administration to grant general licenses or narrow emergency exemptions to the embargo to ensure that U.S. companies of all stripes can assist in preventing and responding to a subsea well leak. The Commerce Department and the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control have granted licenses to some U.S. companies that operate in Cuban waters, including those that could help with oil spill preparation and response. Both agencies promised to act quickly on any additional approvals that are required. But some say granting a wider exemption is needed so that various companies — including parts manufacturers and vessel and plane operators — can respond quickly. “It’s very complex, so the easiest way is to issue a general license and to make sure that the general license is only to be used during an emergency,” Piñón said. “There are hundreds of companies. We don’t know who is going to have that valve that is going to be needed.” For example, well containment systems developed by the Marine Well Containment Co., a coalition of major Gulf oil producers that formed after last year’s spill, and the Helix Energy Solutions Group were instrumental in the Interior Department’s decision to start granting deepwater drilling permits again this year. Repsol has contracts with MWCC and Helix for their operations in U.S. waters, but not in Cuba. Bromwich said he is not pressuring the Treasury to issue or not issue a general license to companies. “It would be in the national interest to make sure that everything that can be done certainly in U.S. waters is done,” he said. “Whether it goes beyond that, I think, is among the issues that are being discussed in high levels of the government.” Regular talks also continue with Repsol, Bromwich said. But while Cuba appears willing to adopt offshore drilling standards modeled after those in the U.S. and Mexico, Piñón said there needs to be direct talks between the two governments. While the embargo tightened during the George W. Bush administration, the Obama administration has loosened some sanctions, including easing specific travel restrictions in January. One challenge will be the politics in Florida, which will again be a swing state in the 2012 election. The state includes critics of any oil or gas drilling near the state’s coastline, along with hard-line Cuban refugees who wince at any melting of relations with the Castro regime. Florida congressional members from both parties have offered bills punishing companies that operate in Cuba. Republicans on Capitol Hill, and potentially on the presidential trail, could also accuse the Obama administration of focusing more on shoring up Cuba’s domestic energy production rather than at home. But Florida political observers say any concern about fiddling with the embargo runs a distant second to the state’s economic doldrums and the devastating impact that a spill could have on the Sunshine State. “It’s much more of an issue for the Republican candidates than it is for the administration,” said Florida Republican strategist Ana Navarro. “I frankly don’t think the administration cares about the hard-lined Cuban-American vote, and I don’t think the hard-lined Cuban-American vote cares for the administration. And I don’t think that’s changing anytime soon.” |

Can Cuba Recover from its De-Industrialization? I. Characteristics and Causes

By Arch Ritter

[Note: a subsequent Blog Entry will analyze “Consequences and Courses of Action” ]

Since 1989, Cuba has experienced a disastrous de-industrialization from which it has not recovered. The causes of the collapse are complex and multi-dimensional. Is it likely that the policy proposals of the Lineamientos approved at the VI Congress of the Communist Party of Cuba will lead to a recovery from this collapse? What can be done to reverse this situation?

One of the last Cane-Harvesting Machines Fabricated in Cuba, en route to its Destination, November 1994

One of the last Cane-Harvesting Machines Fabricated in Cuba, en route to its Destination, November 1994

Perhaps it should be noted to begin with that the manufacturing sector of many if not most high income countries have shrunk as a proportion of GDP and especially in terms employment. This has been due to the migration of labor-intense manufacturing to lower wage countries, most notably China and India, as well as technological change and rising labor productivity in many areas of manufacturing. However, given Cuba’s income levels and its historical record, it could and should be expanding its manufacturing base and perhaps even increasing employment in the sector rather than remaining in melt-down phase

I. Characteristics of Cuba’s De-Industrialization, 1989-2010

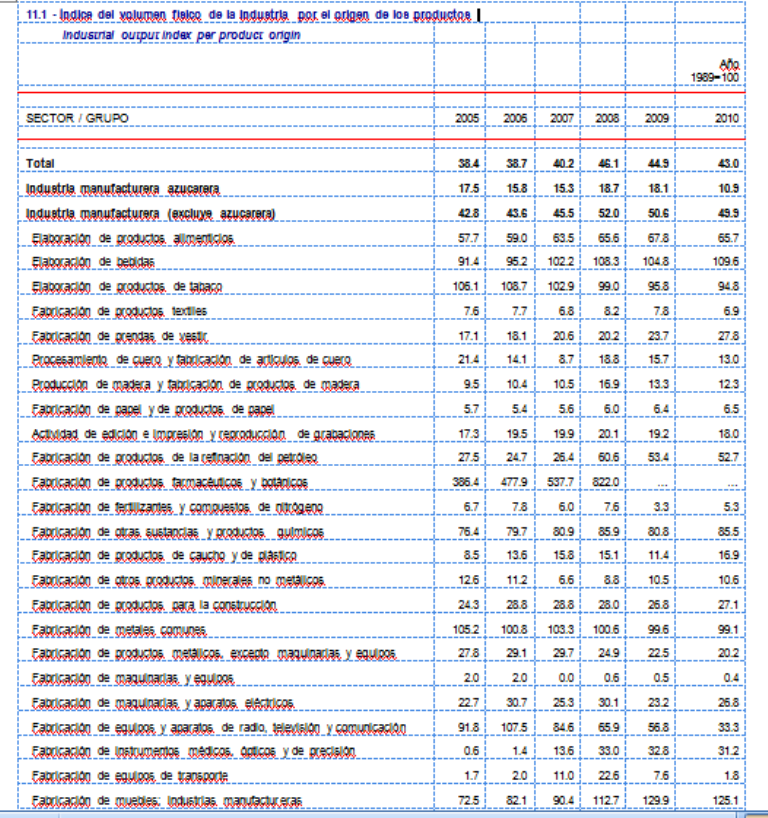

The accompanying Charts and Tables, all using data from Cuba’s Oficina Nacional de Estadisticas, indicate the severity of Cuba’s manufacturing situation.

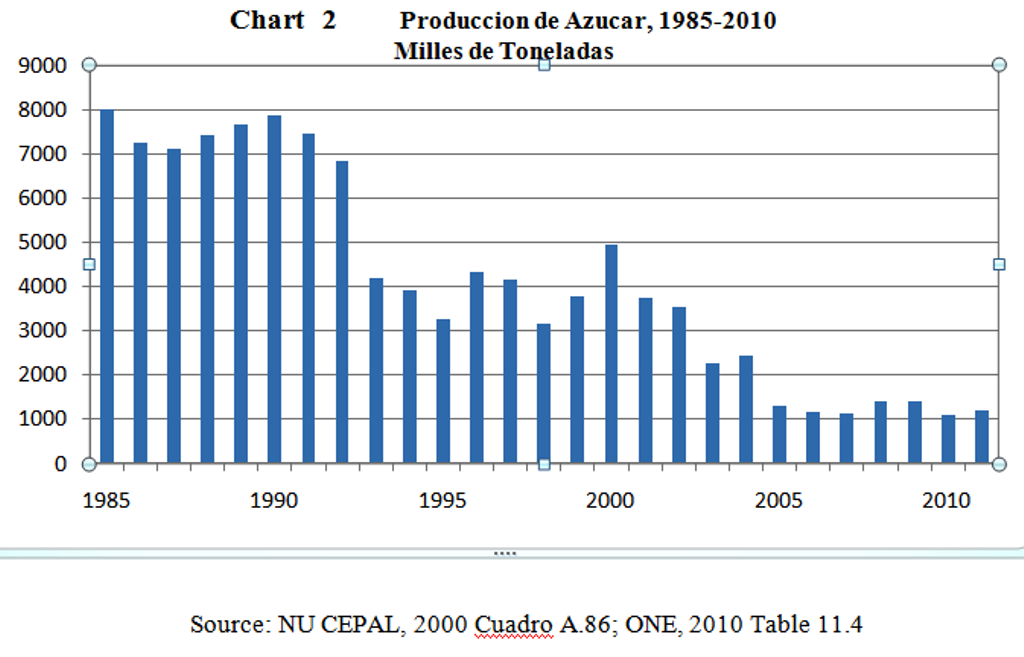

Chart 1 illustrates the almost 60% decline in the physical volume of industrial output – excluding sugar – from 1989 to 1998. By the year 2010, the level of output was at 49.9% of the 1989 level. This does not constitute a recovery.

The physical volume of output by destination is presented in Appendix Table 11.2 below. This Table indicates industrial output including sugar in 2010 was at 43% of its 1989 volume. Products for Consumption were at 81.8% of their 1989 value in 2010. Some product areas had improved, namely manufactures for consumption and “other manufactures” but food drink and tobacco production were at 71.5% of their 1989 volume. Footwear and clothing were at 21.8% of their 1989 volume. Equipment production had almost totally disappeared and was at 6.6% of their 1989 volume in 2010. Intermediate products were at 34.7% of their 1989 volume, despite a near 50% increase in volumes of mineral extraction. .

The physical volume of output by destination is presented in Appendix Table 11.2 below. This Table indicates industrial output including sugar in 2010 was at 43% of its 1989 volume. Products for Consumption were at 81.8% of their 1989 value in 2010. Some product areas had improved, namely manufactures for consumption and “other manufactures” but food drink and tobacco production were at 71.5% of their 1989 volume. Footwear and clothing were at 21.8% of their 1989 volume. Equipment production had almost totally disappeared and was at 6.6% of their 1989 volume in 2010. Intermediate products were at 34.7% of their 1989 volume, despite a near 50% increase in volumes of mineral extraction. .

Volumes of industrial output by origin or industrial sub-sector are presented in Appendix in Table 11.1 Some manufacturing sub-sectors have virtually disappeared with production at very low levels as a percentage of 1989 levels. For example, for the following sectors, 2010 levels as a percentage of 1989 levels were as follows:

- Textiles: 6.9%

- Clothing: 27.8%

- Paper and paper products: 6.5%

- Publications and recordings: 18.0%

- Wood products: 12.3%

- Construction Materials: 27.1%

- Machinery and Equipment: 0.4%

On the other hand, pharmaceutical production increased dramatically, with 2008 production at 822% of the 1989 level. Tobacco, drinks (presumably alcoholic) and metal products were approximately at the 1989 levels. But almost everything else was around 25% of the levels of 1989 or less.

The collapse of the sugar agro-industrial complex is well known and is illustrated in Chart 2.

There are a variety of reasons for the collapse of the industrial sector.

1. The initial factor was the ending of the special relationship with the Soviet Union that subsidized the Cuban economy generously for the previous 25 years or so. This resulted from the shifting of the Soviet Union to world prices in its trade relations with Cuba rather than the high prices for Cuba’s sugar exports as well as an end to the provision of credits to cover Cuba’s continuing trade deficits with the USSR. The break-up of the Soviet Union and recession in Eastern Europe also damaged Cuba’s exports. These factors reduced Cuba’s imports of all sorts, especially of imported inputs, replacement parts, and new machinery and equipment of all sorts. The resulting economic melt-down of 1989-1993 reduced investment to disastrous levels and resulted in cannibalization of some plant and equipment for replacement parts. The end result was a severe incapacitation of the manufacturing sector.

2. The technological inheritance from the Soviet era as of 1989 was also antiquated and uncompetitive, as Became painfully apparent after the opening up of the Soviet economy following Perestroika.

3. Since 1989, levels of investment have been continuously insufficient. For example, the overall level of investment in Cuba in 2008 was 10.5% of GDP in comparison with 20.6% for all of Latin America, according to UN ECLA, (2011, Table A-4.)

4. Maintenance and re-investment was also de-emphasized even before 1989. After 1989, maintenance and re-investment were a category of economic activity that could be postponed during the economic melt-down – for a little while. But over a longer period of time, lack of adequate maintenance of the capital stock has resulted in its serious deterioration or near destruction. This can be seen graphically by the casual observer with the dilapidated state of housing in Havana and indeed the frequent “derrumbes” or collapse of houses and abandoned urban areas.

5. The dual monetary and exchange rate system penalizes traditional and potential new exporters that receive one old (Moneda Nacional) peso for each US dollar earned from exports – while the relevant rate for Cuban citizens is 26 old pesos to US$1.00. This makes it difficult if not impossible for some exporters and was a key contributor to the collapse of the sugar sector.

6. The blockage of small enterprise for the last 50 years has also prevented entrepreneurial trial and error and the emergence of new manufacturing activities.

7. Finally, China has played a major role in Cuba’s de-industrialization as it has done with other countries as well. China has major advantages in its manufacturing sector that have permitted its meteoric ascent as a manufacturing power house. These include

- Low cost labor;

- An industrious labor force;

- Past and current emphases on human development and higher education;

- A relatively new industrial capital stock;

- Massive economies of scale;

- Massive “agglomeration economies”;

But of particular significance has been its grossly undervalued exchange rate that has permitted it to incur continuing trade and current account surpluses and amass foreign assets now amounting to around US$ 3 trillion. Indeed, in my view, China has cheated in the globalization process and captured the lion’s share of its benefits through manipulation of the exchange rate, and has contributed to the generation of major imbalances for the rest of the world, including both the United States and Cuba among other countries. .

China’s undervalued exchange rate has co-existed with Cuba’s grossly overvalued exchange rate that has been partly responsible for pricing potential Cuban exports of manufactures out of the international market. The result is that Cuba is awash with cheap Chinese products that have replaced consumer products that Cuba formerly – in the 1950s as well as the 1970s – produced for itself.

With respect to the sugar sector, there are a number of factors have been responsible for its decline.

1. Most serious, the sector essentially was a “cash cow” milked to death for its foreign exchange earnings, by insufficient maintenance and by insufficient re-investment preventing productivity improvement.

2. The monetary and exchange rate regimes under which it labored have also damaged it badly. Earning one “old peso” for each dollar of sugar exports has deprived the sugar sector of the revenues needed to sust4ain its operations.

3. Finally the decision by former President Fidel Castro to shut down close to half the industrial capacity of the sector and try to convert former sugar lands to other uses sealed its fate. In view of Cuba’s natural advantages in sugar cultivation, the sophistication and diversity of the whole sugar agro-industrial cluster of activities, the high sugar prices of recent years and the competitiveness of ethanol derived from sugar cane, this decision was foolish in the extreme.

Next: Part II, The Consequences of Deindustrialization and Possible Future Courses of Action. will be published in the next Blog Entry

Posted in Blog, Featured

Tagged Agriculture, Economic Growth, Economic Melt-Down, Energy, General Economic Analyses, Industry, Special Period, Sugar Sector

1 Comment

Oil Diplomacy to the Rescue? Cuban Drilling off Florida Keys to Begin by End of the Year

John Daly,Oil Price; Tuesday, 27 September 20, Courtesy of Jorge R. Piñón.

[Oil Price is a well respected oil price research and analysis publication]

For 51 years the U.S. has imposed an economic embargo against Cuba, severely crippling the island’s economy for its effrontery in choosing a socialist path for development, a policy confirmed and intensified in the wake of the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis.

Now the unlikeliest of economic interests may be bringing the two countries closer together – oil.

Specifically, oil deposits in the Florida Straits between Key West and Cuba.

Spain’s largest oil company, Repsol-YPF, has contracted the massive Italian-made Scarabeo 9 semi-submersible oil rig, currently en route from Singapore, to arrive in the Florida Straits by the end of the year after the end of hurricane season to begin exploring Cuba’s offshore reserves. Repsol-YPF, which drilled Cuba’s first onshore well in 2004, intends initially to drill six wells with the Scarabeo 9 rig.

Cuba, which currently produces a paltry roughly 50,000 barrels of oil per day from onshore sources, is understandably keen to begin exploiting its offshore reserves, which estimates place between 5-20 billion barrels of crude in a 43,000 square-mile drilling area containing 59 maritime fields it has designated off its northern coast. While Fidel Castro’s close ally, Venezuelan Hugo Chávez currently dispatches 120,000 bpd to Cuba on very favorable financing terms, the arrangement is heavily dependent on the friendship between octogenarian Castro and cancer-stricken Chávez, hardly a recipe for permanency.

While Repsol-YPF is the first out of the gate, other concessionaires include Norway’s Statoil ASA, India’s state-owned Oil and Natural Gas Corporation Ltd (ONGC) and Brazilian state oil company Petroleo Brasileiro, or Petrobras.

Note the total absence of U.S. oil companies – that’ll punish those pesky Commies!

While the 1982 United Nations Convention of the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) maritime treaty provides littoral nations with a 200-mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) extending 200 miles offshore for exploiting maritime reserves, in 1977 U.S. President Jimmy Carter signed a treaty with Cuba that essentially split interstate waters and created for Cuba an “exclusive economic zone” extending from the western tip of Cuba northward to roughly 50 miles from Key West, which Havana then divided into 59 parcels for leasing.

So, what is Washington’s view of the latest developments? Depends how close you get to Florida, where politicians rely on the anti-Castro Cuban émigré vote to stay in power.

Congressional leaders like Cuban-born Republican House of Represenatives member Ileana Ros-Lehtinen and U.S. Senator Florida Democrat Bill Nelson would like to see Cuba scrap its offshore drilling plans altogether, a most unlikely scenario.

A more realistic approach is embodied in last week’s visit to Cuba by International Association of Drilling Contractors chief executive Lee Hunt, who as part of a joint Environmental Defense Fund traveled to the island with William Reilly, a former Environmental Protection Agency administrator and co-chair of the White House task force investigating the 2010 BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, Royal Dutch Shell former vice president of deepwater drilling Richard Sears and Environmental Defense senior attorney Fund Dan Whittle to discuss plans to deal with possible oil spills from the Cuban projects, and whether U.S. firms might participate in cleanup activities.

The 64,000 peso question is whether Washington will allow such participation. Despite the embargo the Obama administration has said it will let U.S. companies do business with Cuba’s foreign partners in that context on a case-by-case basis. The reality of a Cuban oil spill having effects on U.S. waters has even allowed a bit of reality to intrude on Ros-Lehtinen’s policies, as she recently observed that “should a disaster occur and Florida’s waters be threatened, U.S. regulations could allow U.S. oil spill mitigation companies to engage in clean-up activities.”

Another potential factor in influencing Washington’s decisions is that Repsol-YPF may not be going it alone, either. Mexican daily La Jornada reported earlier this month that Mexican state oil company Petroleos Mexicanos, more familiarly known as Pemex, is shifting from its former “Mexico first” policy and intends to begin foreign operations, including offshore drilling in Cuba. The development is hardly surprising in light of Pemex’s recent announcement that it spent $1.6 billion to raise its stake in Repsol YPF from 4.8 percent to 9.8 percent, with the idea of creating a strategic partnership. In raising its stake, Pemex said it will unite its votes on the Repsol board of directors with those of Spanish construction company Sacyr Vallehermoso, which owns 20 percent of Repsol’s shares. Pemex seems to be emulating the successful global strategy of Brazil’s Petrobras.

As Pemex, ONGC and Petrobras are all state-owned companies, while the Norwegian government owns a majority share in Statoil ASA, to interfere with these companies’ activities is to roil relations with their parent governments, and in the case of Pemex, such a stiff-necked policy could have ominous implications for U.S. energy security, as according to the U.S. Energy Administration, the United States total crude oil imports now average 9,033 thousand barrels per day (tbpd), with Mexico being the second largest source of U.S. imports, running at 1,319 tbpd.

It may be time for a rethink of U.S. policy towards Cuba. After all, Castro has outlasted the Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, Ford, Carter, Reagan, Bush I, Clinton and Bush II administrations, so it rather seems unlikely that the embargo has produced the desired effect of removing the Cuban government.

And oil spills know no nationality.

OilWells, just off the Via Blanca, the road from Havana to Matanzas, 1999

OilWells, just off the Via Blanca, the road from Havana to Matanzas, 1999

Posted in Blog

Tagged Foreign Investment, International Relations, Petroleum, US-Cuba Relations

Leave a comment

Cuba: A Half-Century of Monetary Pathology and Citizen’s Freedom of Movement

By Arch Ritter

UNIVERSAL DECLARATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS

Article 13. (1) Everyone has the right to freedom of movement and residence within the borders of each state. (2) Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country. Article 30. Nothing in this Declaration may be interpreted as implying for any State, group or person any right to engage in any activity or to perform any act aimed at the destruction of any of the rights and freedoms set forth herein.In December 2009, I made a formal invitation to two Cuban citizens to visit Canada, following the official “Procedure for Inviting a Cuban National to Visit Canada” as laid out by the Cuba’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MINREX). I paid the required Consular Fee of $CDN 256.00 for each invitation. The two Cuban citizens invited were Yoani Sanchez and Miriam Celaya. I thought naively and foolishly that while Yoani Sanchez had been denied the right to leave Cuba a number of times before December 2009 when she had been invited by official institutions, perhaps a personal invitation would be successful. I of course was wrong. The Exit Permits of course were refused. The Consulate of Cuba in Ottawa of course refused to return the $512.00.

The lack of freedom of movement of Cuban citizens is well known. The case of Yoani Sanchez is a cause célèbre and also a public relations disaster for the Government of Cuba. A number of analysts have written eloquently on the practice of the Cuban Government to dishonor its commitment to Article 13 of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights cited above. (See Ana Julia Faya: Nosotros tampoco viajamos libremente a Cuba, “Los permisos de entrada y salida del país son una violación de los derechos de los cubanos” and Haroldo Dilla Alfonso, “The (Non) Right of Cubans to Travel, Havana Times, February 01, 2011”

Sergio Diaz-Briquets has presented a comprehensive and comparative analysis of the Consular Fees charged by the Governmemt of Cuba for the acquisition of a passport, its renewal while abroad, and various other consular services (ASCE Conference 2010). He concluded that the Consular Fees are simply abusive. (See S. Diaz-Briquets, Government-Controlled Travel Costs to Cuba and Costs of Related Consular Services: Analysis and International Comparisons )

However, the most egregious violation of the freedom of movement of Cuban citizens lies less in the exorbitant consular fees that are routinely charged to Cubans abroad for consular services and the Exit Permit controls over Cuban citizens and more in Cuba’s monetary and exchange rate system. Cuba’s currency has been inconvertible for 50 years and the dual monetary and exchange rate system has prevailed for the last 20 years. Currency inconvertibility means that citizens can not routinely change their earnings for foreign currencies in order to travel freely. Instead, from 1961 to 1992 they have had to get permission from the Government to exchange their earnings in Moneda Nacional into a foreign currency. On the other hand, anyone on official government business or activities sanctioned by the Government could get access to foreign exchange. This meant that for the average citizen travel was highly restricted unless one could find a foreign sponsor to pay the bills.

With the dual monetary system coming into play in the early 1990s, the economic powerlessness of most Cuban citizens was further intensified. With the collapse of the value of the “old peso” (Moneda Nacional) vis-a-vis the US dollar (and then the convertible peso CUC) the purchasing power of earnings in the official economy also collapsed. At the exchange rate for Moneda Nacional to the US dollar at around 26 to 1, the average monthly income is somewhere around US$ 20.00. Cuba’s monetary system impoverishes Cuban citizens in terms of the international transferability of their earnings from work.

In order to travel abroad, Cuban citizens now have three options. First, they can work for some branch of the government, mixed or state enterprises or organizations such as Universities for which travel abroad on official business can occur. Second, they can marry a foreigner for convenience or in sincerity – Spaniards and Ecuadoreans have been predominant recently – who then provides hard currency funding for travel abroad. Or third, they can now convert their Moneda Nacional earnings into Convertible pesos at the ratio of 26 to 1 and then acquire foreign currency through various channels with the convertible pesos. For most citizens, travel abroad is essentially blocked by the monetary and exchange rate systems.

The central planning system and the generalized controls on the economy adopted in 1960-61 meant that inconvertibility would have happened in any case. However, inconvertibility occurred under the watch of Che Guevara, who at the time was President of the National Bank and Minister of Finance as well as Minister of Industries (which included Basic Industry, Light Industry, Mining, Petroleum, and the sugar mills. Guevera was the indisputable “czar” of the Cuban economy.

Monetary inconvertibility and the accompanying loss of freedom of movement is one of Che Guevara’s gifts to the Cuban people. This has been compounded by the monetary and exchange rate policies of the Fidel and Raul Castro Presidencies after about 1990, which generated the dual system and which have so far been unable to come to grips with it and establish a unified and convertible currency.

Posted in Blog, Featured

Tagged Che Guevara, Fidel Castro, Freedom of Movement, Human Rights, International Relations, Monetary System

Leave a comment

Larry Catá Backer, GLOBALIZATION AND THE SOCIALIST MULTINATIONAL: CUBA AND ALBA’S GRANNACIONAL PROJECTS AT THE INTERSECTION OF BUSINESS AND HUMAN RIGHTS

At the 2010 Conference of the Association for the Study of the Cuban Economy, Larry Catá Backer presented a challenging and insightful analysis of the new forms of socialist multinational enterprise being used by Cuba and Venezuela from the perspective of how practices of state bartering of labor may run counter to emerging global frameworks for human rights and economic activity.

” That collision is examined against (1) recent litigation in which Cuba has been accused (directly or indirectly) of violating international law by operating enterprises based on forced labor, (2) the possibility of conforming to the OECD’s Guidelines on Corporate Governance of State Owned Enterprises, and (3) the possibility that these enterprises will not be able to conform to the United Nation’s developing business and Human Rights project.”

Larry Catá Backer is the W. Richard and Mary Eshelman Faculty Scholar

and Professor of Law, Professor of International Affairs, Pennsylvania State University. He is the author of the legal Blog Law at the End of the Day,

and Professor of Law, Professor of International Affairs, Pennsylvania State University. He is the author of the legal Blog Law at the End of the Day,

The complete Essay is available here:

INTRODUCTION

This paper considers Cuba’s new efforts at global engagements through the device of the grannacional in its ALBA framework. The paper starts by examining the basic theory and objectives of the grannacional generally as articulated in ALBA publications as the

“concepto grannacional” that serves as the organizing framework of these multi-state socialist enterprises. It considers distinctions and implications for the division of grannacional efforts between proyectos grannacionales and empresas grannacionales. It then focuses on a specific grannacional-related project—the Misión Barrio Adentro (MBA), a socio-political barter project in which Cuba exchanges doctors and other health field related goods and services under its control for Venezuelan goods, principally petroleum.

(Convenio 2000). MBA is analyzed as an example of the application of Cuban-Venezuelan approach to economic and social organization through the state. The MBA is also useful as an illustration of the difficulties of translating that approach into forms that might conform with emerging global expectations of economic conduct by private and state actors. The recent litigation in which Cuba has been accused (directly or indirectly) of violating international law by operating enterprises based on forced labor by both laborers and doctors, and soft law systems of governing business conduct (Galliot 2010) serve as a backdrop against which this analysis is undertaken. For Cuba programs like MBA have served as a means

of engaging in economic globalization and of leveraging its political intervention in the service of its ideological programs in receptive states like Venezuela. (Bustamante & Sweig 2008; Kirk & Erisman 2009). It has also provided a basis for expanding Cuba’s commercial power by permitting large scale state-directed barter transactions. But when bartering involves labor as well as capital, the fundamental premises of the ALBA system—and Cuban ideological notions of the fungibility of labor and capital in the service of the state—may collide with emerging global frameworks for human rights and economic activity. That collision is examined against (1) recent litigation in which Cuba has been accused (directly or indirectly) of violating international law by operating enterprises based on forced labor, (2) the possibility of conforming to the OECD’s Guidelines on Corporate Governance of State Owned Enterprises, and (3) the possibility that these enterprises will not be able to conform to the United Nation’s developing business and Human Rights project. MBA serves as a template both to understand the character of the operationalization of social sector grannacionales and also to illustrate the way in which these projects raise significant questions of international law compliance, especially the ability of these enterprises to comply with emerging standards of business conduct.

CONCLUSION

Cuba has begun the process of seriously integrating itself within an international economic architecture. It is seeking to engage in globalization on its own terms. It means to use global engagement to open another front in its great ideological campaigns against the emerging conventional system private markets driven economic globalization in favor of a more state directed and controlled system of commercial activity among states. An important venue for that

engagement has been through ALBA. ALBA has served as a vehicle for regional integration through which the ideology driving the Cuban state is leveraged, applied and furthered by others, principally Venezuela. In the form of ALBA’s grannacional projects

and enterprises, ALBA states seek to mimic, and by mimicking to subvert, the conventional framework for economic globalization.

It is one thing to describe the ideological and functional framework for the grannacional project. It is quite another matter to consider the way these enterprises might operate on a day-to-day basis. And more importantly, it is necessary to consider the implications

of such operation of these supra-national corporations under standards of international soft and hard law. This paper has suggested the contours of the violation exposure of grannacional projects under these international norms. The very ideological foundation of the grannacional projects serves as the basis

for conflict with normative standards in effect elsewhere.

In a command economy in which there is no distinction between the political and economic sphere and where the line between obligations of citizens and of workers is blurred, the difference between a citizen’s duty to the state and involuntary servitude can be quite thin. It is unlikely that international standards will bend to accommodate substantial deviations where the functional effect of state action appears to substantially impede recognized human rights, as those are generally understood. It suggests that while Cuba and the ALBA states may avoid the consequences of breach within their own territories, their assets elsewhere may be exposed to actions based on those breaches. And, perhaps more importantly, private and public enterprises of other states will also be exposed to liability for complicity Cuba in Transition in the violations of grannacional enterprises with which they might partner. That can have significant effects on the ability of grannacional enterprises to

forge significant business relationships outside the ALBA area. Global human rights norms, then, might confine grannacional activity to the territory of the sponsoring states more effectively than any sort of politically motivated embargo. The possible exposure of Cuba for human rights violations in connection

with its labor barter transactions illustrates the nature of the problem. Cuba (and ALBA) may well have to pay a price for the choice of their collective form of economic global engagement as it collides with the emerging legal and normative framework for international human rights applies to economic activity that, ironically enough, Cuba has helped to construct.

Cuba’s Anti-Corruption Drive: Second Canadian Trading Company Shut Down

By Marc Frank | Reuters –

HAVANA (Reuters) – Cuba has shut down one of the most important western trading companies in the country as an investigation into alleged corrupt import-export practices broadened to a second Canadian firm, foreign business sources said on Friday.

State security agents on Friday watched who entered the building in Havana’s Miramar Trade Center where Ontario-based Tokmakjian Group, one of the top Canadian companies doing business on the communist-run island has its offices. The company offices of the fourth floor were sealed with a notice that it had been closed by Cuban State Security. “We received notice on Monday from the foreign ministry and the Council of State, which is the procedure in such cases, to stop all dealings with the Tokmakjian Group,” said an employee of a Cuban company that does business with the firm. Like other people who spoke to Reuters about the clampdown on the company, she asked that her name not be used.

Miramar Trade Center

Tokmakjian Group is estimated to do around $80 million in business annually with the Caribbean island, mainly selling transportation, mining and onstruction equipment. The company is the exclusive Cuba distributor of Hyundai, among other brands, and a partner in two joint ventures replacing the motors of Soviet-era transportation equipment. Company officials were not immediately available for comment.

Cuban authorities shut down Canadian firm Tri-Star Caribbean on July 15 and arrested company president Sarkis Yacoubian. The company, considered a competitor of Tokmakjian Group, did around $30 million in business with Cuba. “Apparently Tri-Star Caribbean was just the beginning. They brought in more than 50 state purchasers for questioning, arrested some of them and broadened the investigation from there,” a western businessman said. “As far as I know up to now just Canadian firms are involved, but you can bet every state importer and foreign trading company in the country is on edge,” he said.

Cuban President Raul Castro has made fighting corruption a top priority since taking over for his ailing brother Fidel in 2008, and in the past year a number of Cuban officials and foreign businessmen have been charged in graft cases.

Tri-Star Caribbean did business with around half of the 35 Cuban state companies authorized to import, from tourism, transportation and construction to the nickel and oil industries, communications and public health. The whereabouts of the man who founded the family business, Cy Tokmakjian, of Armenian heritage, born in Syria and educated in Canada, was not clear on Friday.He was last seen by Reuters a week ago, the day after his offices were sealed, but another western businessman said he had been detained by Cuban authorities. “They picked up Cy on Saturday and I heard his wife and at least one of his kids flew ion to see what they could do,” he said.

Cuba’s state-run media rarely reports on corruption related investigations until they are concluded and those charged are sentenced.

Tokmakjian, a former mechanic, is a self-made millionaire with interests in Canada and other countries besides Cuba, where he is a well known figure. He made his first deal with the Caribbean island in 1988.

President Castro, a general who headed Cuba’s Defense Ministry for 49 years, has cracked down on corruption as part of his efforts to revive the country’s sagging economy, but to date has done little to change the conditions that foster it, such as low salaries and lack of transparency. There is no open bidding in Cuba’s import-export sector and state purchasers who handle multimillion-dollar contracts earn anywhere from $50 to $100 per month.

Castro has moved military officers into key political positions, ministries and export-import businesses and in 2009 stablished the Comptroller General’s Office with a seat on the Council of State. A source close to the Tri-Star Caribbean case said the Comptroller General’s Office had been brought into the investigation, indicating it most likely was targeting high level officials.

Castro’s crackdown has resulted in the breaking up of high-level organized graft in the civil aviation, cigar and nickel industries, at least two ministries and one provincial government. An investigation into the communications sector and another into shipping are also under way.

Posted in Blog

Tagged Corruption, Cuba-Canada Relations, Foreign Investment, Foreign Trade, Illegalities

Leave a comment

As Cuba plans to drill in the Gulf of Mexico, U.S. policy poses needless risks to our national interest

The Center for Democracy in the Americas’ Cuba Program has published a thorough exploration of Cuba’s petroleum exploration plans and prospects and the implications for United Sates” policy towards Cuba generally and in the oil sector more specifically.It is the most thorough and well-balanced assessment of this issue that I have seen. (Apologies for not getting some publicity out on this work earlier.)

Here is a hyperlink to the study. The Preface and the last coupleof Concluding comments are als presented beliw.

As Cuba plans to drill in the Gulf of Mexico, U.S. policy poses needless risks to our national interest

The Center for Democracy in the Americas’ Cuba Program; February 2011

PREFACE

This year Cuba and its foreign partners will begin drilling for oil in the

Gulf of Mexico. Drilling will take place as close as 50 miles from Florida

and in sites deeper than BP’s Macondo well, where an explosion in April 2010

killed 11 workers and created the largest oil spill ever in American waters.

Undiscovered reserves of approximately 5 billion barrels of oil and 9 trillion

cubic feet of natural gas lie beneath the Gulf of Mexico in land belonging

to Cuba, according to the U.S. Geological Survey, although Cuba’s estimates

contain higher figures. The amount actually recoverable remains to be seen.

Finding oil in commercially viable amounts would be transformative for

Cuba. Revenues from natural resource wealth have the potential to provide

long-sought stability for Cuba’s economy and are likely to significantly alter

its relations with Venezuela and the rest of Latin America, Asia and other

leading energy producing and consuming nations. Discoveries of commercially

viable resources would also have an enormous impact upon the Gulf

environment shared by Cuba and the United States.

The U.S. embargo against Cuba, a remnant of the Cold War, is an obstacle

to realizing and protecting our interests in the region. Not only does it prohibit

U.S. firms from joining Cuba in efforts to extract its offshore resources, thus

giving the competitive advantage to other foreign firms, but it also denies

Cuba access to U.S. equipment for drilling and environmental protection—an

especially troubling outcome in the wake of the disastrous BP spill. The embargo compels Cuba’s foreign partners to go through contortions—such

as ordering a state of the art drilling rig built in China and sailing it roughly

10,000 miles to Cuban waters—to avoid violating the content limitations

imposed by U.S. law.

Most important, due to the failed policy of isolating Cuba, the United

States cannot engage in meaningful environmental cooperation with Cuba

while it develops its own energy resources. Our government cannot even

address the threat of potential spills in advance from the frequent hurricane

activity in the Gulf or from technological failures, either of which could put

precious and environmentally sensitive U.S. coastal assets—our waters, our

fisheries, our beaches—at great peril.

The risks begin the moment the first drill bit pierces the seabed, and

increase from there. Yet, our policy leaves the Obama administration with

limited options:

• It could do nothing.

• It could try to stop Cuba from developing its oil and natural gas, an alternative

most likely to fail in an energy-hungry world, or

• It could agree to dialogue and cooperation with Cuba to ensure that drilling

in the Gulf protects our mutual interests.

Since the 1990s, Cuba has demonstrated a serious commitment to protecting

the environment, building an array of environmental policies, some based

on U.S. and Spanish law. But it has no experience responding to major

marine-based spills and, like our country, Cuba has to balance economic

and environmental interests. In this contest, the environmental side will

not always prevail.

Against this backdrop, cooperation and engagement between Cuba and

the United States is the right approach, and there is already precedent for it.

During the BP crisis, the U.S. shared information with Cuba about the

spill. The administration publicly declared its willingness to provide limited

licenses for U.S. firms to respond to a catastrophe that threatened Cuba. It also

provided visas for Cuban scientists and environmental officials to attend an

important environmental conference in Florida. For its part, Cuba permitted

a vessel from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to look for damage in Cuban waters. But these modest measures, however welcome,

are not sufficient, especially in light of Cuba’s imminent plans to drill.

Under the guise of environmental protection, Reps. Ileana Ros-Lehtinen

and Vern Buchanan, Members of the U.S. Congress from Florida, introduced

bills to impose sanctions on foreign oil companies and U.S. firms that help

Cuba drill for oil, and to punish those foreign firms by denying them the right

to drill in U.S. waters. This legislation would penalize U.S. firms and anger

our allies, but not stop Cuba from drilling, and will make the cooperation to

protect our mutual coastal environment more difficult should problems occur.

Energy policy and environmental protection are classic examples of

how the embargo is an abiding threat to U.S. interests. It should no longer

be acceptable to base U.S. foreign policy on the illusion that sanctions will

cause Cuba’s government to collapse, or to try to stop Cuba from developing

its oil resources. Nor should this policy or the political dynamic that sustains

it prevent the U.S. from addressing both the challenges and benefits of Cuba

finding meaningful amounts of oil in the Gulf of Mexico.

The path forward is clear. The Obama administration should use its

executive authority to guarantee that firms with the best equipment and

greatest expertise are licensed in advance to fight the effects of an oil spill.

The Treasury Department, which enforces Cuba sanctions, should make clear

to the private sector that efforts to protect drilling safety will not be met with

adverse regulatory actions. The U.S. government should commit to vigorous

information sharing with Cuba, and open direct negotiations with the Cuban

government for environmental agreements modeled on cooperation that

already exists with our Canadian and Mexican neighbors.

Most of all, the administration should replace a policy predicated on Cuba

failing with a diplomatic approach that recognizes Cuba’s sovereignty. Only

then will our nation be able to respond effectively to what could become a

new chapter in Cuba’s history and ours.

There is little time and much to do before the drilling begins.

Sarah Stephens; Executive Director

RECOMMENDATIONS (7 to 9)

Accept the Reality of Cuba’s Oil Program

7. The United States is served by an economically stable Cuba.

Cuba is currently undertaking significant economic reforms. It has announced

layoffs for 500,000 state workers and proposed economic reforms to enable

Cuba’s nascent private sector to absorb them. More Cubans working in the

private economy will provide more Cubans with greater personal autonomy.

If Cuba is able to develop its hydrocarbon reserves in a manner that places

the Cuban economy on a more sustainable footing, this could lessen the

possibility of another migration crisis or other forms of instability.

Cuba’s economic plans include its vision for oil. As Lisa Margonelli said at

the National Foreign Trade Council, “Cuba has an elaborate plan to be a port,

to be a source for refined products, to serve as a bonded warehouse for the

distribution of goods throughout the region. Despite being a small country,

they are thinking about energy and their economic future in a big way.”

Economies dependent on the extraction of natural resources are often

unsuccessful. Finding oil can be a double-edged sword. Cuba having foreign partners will help them guide the process of incorporating these resources

into its economy over time. Given the time required to monetize the oil,

Cuba should aim for having healthier economic and political institutions

operating before the oil money starts to flow.

8. Cuba’s potential contribution to the regional energy market could be valuable to the U.S.

Professor Soligo cites several benefits to the United States if Cuba is able to

realize the potential of its oil resources in the Gulf of Mexico. In his remarks

at the National Foreign Trade Council, Professor Soligo said, “Whoever

develops these resources it would be good for the United States.”

For example, Professor Soligo observed that Cuba has the potential to

develop an ethanol industry, and the U.S. cannot meet its ethanol targets

without imports. Policy changes would be required to allow Cuba access

to the U.S. market, and would provide substantial environment and energy

policy benefits were they to be made. While Cuba has opposed using corn

for ethanol, it has the resources to produce cellulosic material in its place.

Lisa Margonelli observes, “It is in U.S. interests to create fair price

competition for Cuban oil rather than forcing them into one-buyer fixed

price contracts with China. Securing the flow of more oil into the world

spot market has been one of the few effective American responses to OPEC’s

pricing power since 1979.”

9. U.S. policy should welcome the geo-political changes oil could

usher in.

Cuba is unlikely to disassociate itself from Venezuela or China regardless of

what the U.S. does. Still, Cuba’s post-revolutionary history is defined, in part,

by its dependence on the former Soviet Union and later on Venezuela, and

the development of its offshore resources could give the island’s economy

greater independence than it has enjoyed to date.

If Cuba were no longer dependent on Venezuela, and the U.S. engaged

in cooperative efforts on oil and the environment, we would be establishing

deeper and more positive ties with Cuba’s government and signal to its citizens

that we have a stake in their success.

as c uba p lans t o dr ill, u.s. p olicy p uts our nat ional interest at r isk

10. U.S. policy toward Cuba should no longer be predicated on Cuba failing.

For more than 50 years, U.S. policy toward Cuba has been predicated on

regime change; the Cuban government being overthrown, or being strangled

into submission by U.S. sanctions or the pressure of diplomatic isolation.

It should no longer be acceptable to base U.S. foreign policy on the illusion

that sanctions will cause Cuba’s government to collapse, or even stop

Cuba from developing its oil resources. Nor should the inertia exhibited by

this policy or the political dynamic that sustains it prevent the U.S. from

addressing both the challenges and benefits of Cuba finding meaningful

amounts of oil in the Gulf of Mexico.

The embargo imposes real constraints on the government’s ability to

protect our nation against the potentially grave consequences of an environmental

disaster linked to drilling for oil in the Gulf of Mexico by Cuba

and its foreign partners.

As one expert told us, “Cuba is a country with whom we have virtually

no diplomatic or commercial relations. If a well gets out of control, we have

no genuinely effective recourse if we’re waiting for a transition in Cuba’s

government to occur.”

If Cuba brings commercially viable amounts of oil out of the Gulf, the

embargo becomes even more irrelevant than it is today. How should the U.S.

respond, especially now that drilling in 2011 is a fait accompli and will take

place approximately 50 miles from our shores?

The U.S. should respond by changing the policy, in the ways we describe

here, so the national interest of the United States can be realized and protected.

Posted in Blog

Tagged International Relations, Mineral Sector, Petroleum, US-Cuba Relations

Leave a comment

“The Economist” on Taxes in Cuba: Get used to it

The Castros’ subjects get acquainted with that other sure thing

Sep 17th 2011 | HAVANA | from the print edition

Half your monies are belong to us

Half your monies are belong to usWHEN Raúl Castro, Cuba’s president, announced last year that the government would cut its payroll by up to 20% and promote self-employment, state media hailed the birth of a “tax culture”. As most Cubans had never paid income tax, the Communist newspaper published a guide to the concept. Government economists predicted a 400% increase in tax revenue from individuals.

The experiment has been bumpy. Last October Cuba published a tax code for workers in its 181 newly authorised occupations, ranging from furniture repairer to professional clown. As in the early 1990s, the last time Cuba tried economic liberalisation and taxation, the rates were punitive: 10% on turnover, 25% for social security and up to 50% on income. Such levies discouraged some people from risking self-employment. By May applications for job licences were tailing off.

Moreover, Mr Castro failed to beef up the National Tax Administration Office (ONAT), which was soon overwhelmed by filings. That has delayed revenue collection, and allowed both intentional and inadvertent tax cheats to go unpunished. “They seem even more confused about this than we are,” says Ernesto, an engineer who obtained a licence to set up a plumbing business in March. He admits that he simply guesses how much he has earned each month and declares a tenth as much.

But Mr Castro seems more flexible than his brother and predecessor Fidel, who blamed the self-employed for sowing inequality and happily taxed private firms out of existence. Eager to find jobs for up to 1m public workers he plans to fire, he has carved out exemptions from the social-security tax and twice increased the scope for deductions. He has also ordered ONAT to retrain its staff and hire new inspectors. “There certainly is an element of making up the rules as they go along,” says one European diplomat based in Havana. “But Raúl seems totally determined to make this work.”

Further reforms are on the way. By the end of 2011, Cubans will be allowed to buy and sell homes and cars. It remains to be seen how long they will accept taxation without representation. “They happily take our taxes,” says Michel, a barber who recently founded a business. “But they still keep their secrets.”

Posted in Blog

Tagged Economic Reforms, Fiscal Policy, Self-Employment, Small Enterprise, Taxation

Leave a comment

G. B. Hagelberg, Analyst and Friend of Cuba. His Last Work: ¨Cuban Agriculture: Limping Reforms, Lame Results”

By Arch Ritter

Cubans and friends of Cuba will lament the recent death of G.B. Hagelberg, a long time and highly respected analyst of Cuban agriculture, most notably the sugar sector. Hagelberg had a deep and long term knowledge of the sugar agro-industrial complex in the Caribbean generally including Cuba, having served as the resident sugar adviser of the government of Barbados from 1960 to 1968 and from 1980 to 1986. He was the author of numerous publications, including a book-length study entitled The Caribbean Sugar Industries: Constraints and Opportunities (1974). More recently his work focused more on Cuban agriculture and he authored a variety of works in this area. His last analysis. referred to here, was originally entitled “Cuban Agriculture: Limping Reforms, Lame Results”. but was re-labelled “Agriculture: Policy and Performance”. It was presented at the Association for the Study of the Cuban Economy (ASCE) Conference in August 2011.

Some central conclusions of this last work are presented below and the complete essay can be found here, courtesy of ASCE and especially Joaquin Pujol. It will be generally available on ASCE’s Website for the 2011 Conference soon.

The complete text can be found at this hyper-link:

Hagelberg ASCE 2011, AGRICULTURAL POLICY AND PERFORMANCE

Hagelberg’s Concluding Comments:

Analysts can thank Raúl Castro for a semblance of glasnost. Ironically, it reveals the limits of his perestroika. That enterprise is running the danger of unraveling under the weight of its internal contradictions. If this is not to happen, the realization has to gain ground that “concentration of ownership” (Article 3) is as undesirable in the public as in the private sector of the economy and that competition is the mother of efficiency. Non-functional state monopolies and monopsonies have to be dismantled. Also to be unpicked is the conflation of centralization and planning, a fantasy nowhere more counterproductive than in agriculture. To succeed, farm and agroindustrial policies must be informed by a thorough understanding of the conditions that make these sectors different from other economic activities. Regulation is obviously necessary in such areas as environmental protection, food safety and the prevention of market abuse. But to thrive, Cuba’s agriculture and agroindustry require the government to shift decisively from a controlling to an enabling mode, attending to rural infrastructure investment, research and extension, the reduction of risk from natural causes, financing, and the provision of timely and reliable information.

*********************

In a speech to the National Assembly in July 2008, Raúl Castro returned to his oft-quoted 1994 statement that “beans are more important than cannons.” Over 2007-10, the four calendar years in which he has led the government, bean production averaged 96,400 metric tons annually, against an average of 109,175 tons in the previous four years (ONE, 2011a, Table 1.6). Men who have spent a lifetime running the armed forces may believe that making farm policy is not rocket science. It is surely at least that. After all, a centrally managed economy was first to send a man into space; across the world, the track record of centrally managed economies in agriculture has been less glorious. The measures introduced to boost the home-grown food supply and reduce the need for imports have still to pass the beans test, and Cuba’s agricultural malaise rumbles on.