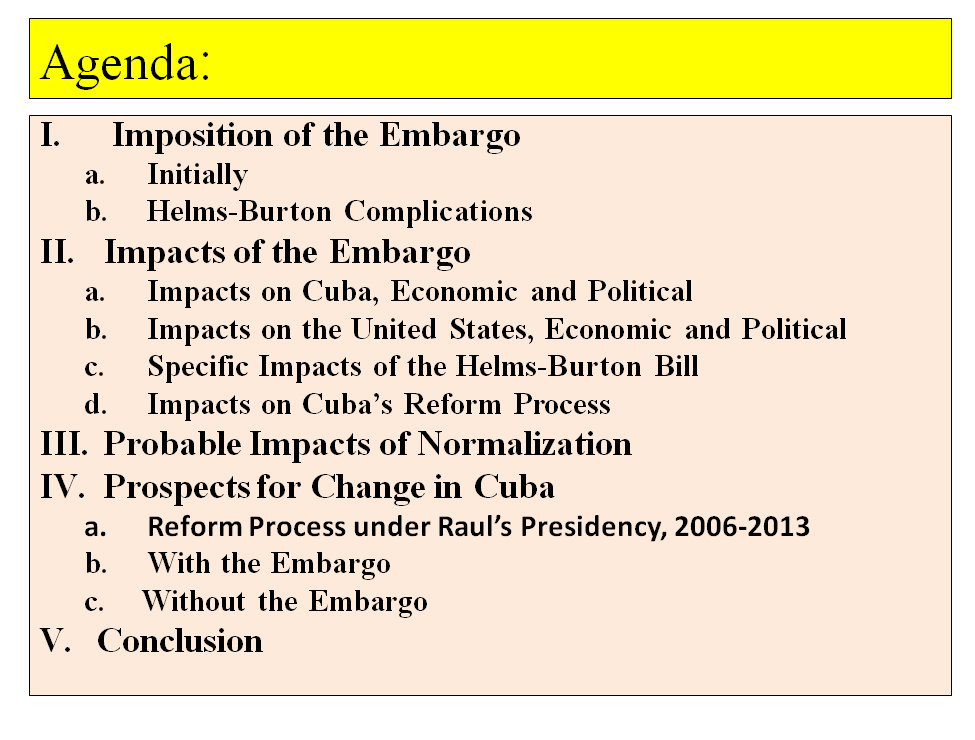

December 17, 2013 | “Down with Capital, Long Live Capital!” Pedro Campos HAVANA TIMES

December 17, 2013 | “Down with Capital, Long Live Capital!” Pedro Campos HAVANA TIMES

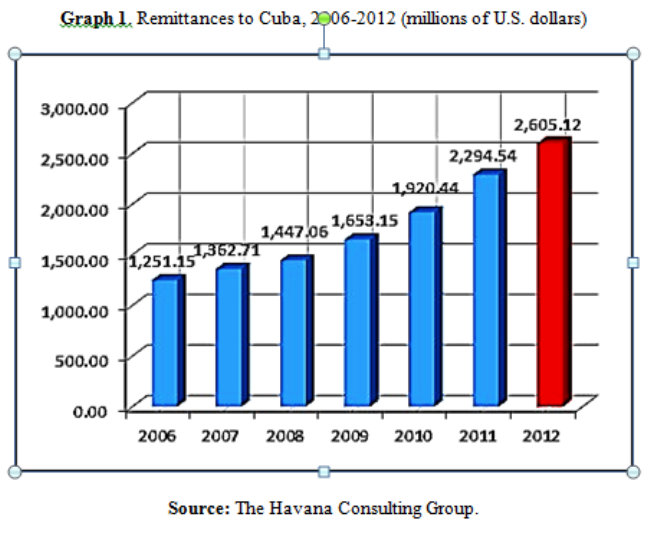

Those in Cuba who once bet on the complete expropriation and nationalization of foreign capital today beseech foreign capital to come in their aid, offering investors every imaginable guarantee. The Cuban State economy is in crisis, but not as a result of the imperialist blockade or the collapse of the Soviet Union, as the defenders of “State socialism” often say. The main reasons for the crisis must be looked for in more than fifty years of nearly-absolute state control, in the extreme centralization of decisions regarding how and how much of the billions of rubles received as subsidies from the former Soviet Union and the billions of Cuban pesos and hard currency produced by the working class were spent over this period of time, in the all-encompassing intervention of the State in the economy through domestic and foreign trade monopolies. It is to be found, also, in the State’s almost complete control over the means of production, in the nationalization of international capital, the capital of Cuba’s high and petite bourgeoisie, of free, individual and family workers – recall the “revolutionary offensive” of 1968 – of cooperatives and worker associations. The low salaries of workers, the maintenance of wage labor for the State, the financial imbalances generated by high spending in gigantic State institutions – such as the Armed Forces, State Security, the Party’s political and grassroots apparatuses, propaganda networks entirely subordinated to the State / Party / government, the country’s unwieldy foreign service – and international campaigns aimed at securing support for the government are some of the other causes behind the crisis. All of this could be summed up as the catastrophic result of that series of aberrant, archaic and dogmatic conceptions that Stalinism developed under the banner of Marxism-Leninism. According to the Stalinist logic, a political and military elite is to determine and regulate a society’s laws, economy, way of life and just about everything else in the name of the communist Party, the revolution, socialism and the working class – so-called “real socialism”, whose only real characteristics have been the absence of democracy and the refusal to socialize political and economic power. I have insisted on this elsewhere: unless the economic, political and social failure of this false socialism is acknowledged, the mistakes made will never truly be rectified. Those who defend this unjust system and now unscrupulously try to “update” it mistakenly identify the Cuban revolution with the Cuban government/State/Party that has made and continues to make every absurd mistake, “validating” the claims of right-wingers worldwide regarding the “unviability of socialism” (perhaps the best help global capitalism could hope for). Today, Cuba’s State economy can no longer rely on massive subsidies from the Soviet Union, Venezuela is experiencing a serious economic crisis and cannot continue to provide the aid Chavez offered the island. Likewise, the governments of powerful allies such as Russia, China and Brazil only offer credits that must be repaid. The bureaucratic apparatus of Cuba’s government/Party/State has refused to consider the truly socialist option: it has refused to share the country’s economic power with the people, with Cubans at home and abroad, with the workers. It has refused to allow workers to participate in the administration, management and revenue-collection of State companies and to grant full freedom to the self-employed and cooperatives, instead subjecting these to regulations, experiments and all manner of toing-and-froing. Naturally, workers identify less and less with a State that only caters to the interests of an elitist, bureaucratic caste which continues to determine the country’s laws, investments, estates and the lives of people. Faced with this complex situation, torn apart by its own contradictions and flip-flopping, the Cuban government/State/Party has now decided to contract legal matrimony with international capital, in order to be able to continue exploiting Cuban workers with its aid. The ironies of history! The “revolutionary leadership”, thirsty for foreign capital, today assures us it will not nationalize foreign investments made at El Mariel, the immense commercial project dependent on the end of the US blockade / embargo. The same government that blamed international capital – and US capital in particular – of all the world’s evils, that once boasted of having nationalized (placed under State control, to be more accurate) all foreign properties, today swears blind that it will respect international capital and begs, beseeches its powerful northern neighbor to lift the restrictions that prevent US millionaires from showering Cuba with dollars. They are not concerned about the risk that big, transnational companies – particularly US companies – will take possession of the resources and wealth of the “Pearl of the Antilles”, the “Key to the Gulf”, the “World’s Cruise Ship”, offering foreign investors the sweat of Cuban laborers on a silver platter, in order to share with them the surplus value they can squeeze out of workers together. This is typical of the annexationist stance that Cuba’s new Right – which has taken power in “socialist” Cuba – cannot conceal. We are dealing with the same people whose slogan once was “down with Capital”, those who today yell: “long live Capital!” The traditional Cuban Right based in the United States does not conceal its intentions of restoring capitalism on the island. The new Right offers us a pig in a poke, painting itself a “socialist” red while acquiescing to Yankee capital, allegedly excluding the old, “imperialist” capitalists (no, the new ones are “anti-imperialists”), so that the nouveaux riches and bureau-bourgeoisie, allied to and financially dependent on international capital, can survive the inevitable collapse. This comes as no surprise. Many of us in Cuba’s democratic and socialist left have been saying for many years that the bureaucratic State has only two options: coming to an agreement with the Cuban workers and people or with foreign capital. The second alternative has been the one chosen in all places where “State socialism” was essayed, where the powerful, authoritarian elite re-converted back to capitalism and became a new type of bourgeoisie. We are not against foreign investment. The question is who these investments benefit and what type of economy they are to serve, whether they are aimed at overcoming the economic and financial problems of the bureau-bourgeoisie and Cuba’s new Right or at developing the mid-sized and small companies and cooperatives of a socialist economy. During a fund-raising campaign in Miami, President Barack Obama assured Cuban dissidents he would not negotiate with the Cuban government in what is left of his term in office, while speaking of the need to change the United States’ long-standing foreign policy towards Cuba. The Democrats are already scrambling to secure votes from the Cuban and Hispanic communities, in view of the fact that there is a good chance the Republicans will put forth a Cuban-born senator as presidential candidate in the coming elections. If that were to happen and the Republicans won… Many concerns, questions and disagreements must exist in the high echelons of Cuba’s leadership. What did the US president mean? If there are to be no negotiations, the blockade will not be lifted and American investments will not come. What will they do with the Mariel project, its three million containers and their debt to Brazil? What steps could be taken to ensure the inflow of US capital, without putting their political power at risk? If this US president doesn’t lift the blockade, is that possibility to be discarded by Cuba’s current leaders? If the Republicans were to win the coming elections and a man of Cuban origin were to take office, what would they do? Now, has anyone in Cuba’s distinguished government of generals asked the Cuban people what they want? With every new development, what becomes clearer and clearer is that Cuba needs to democratize society, allow all Cubans to freely express our thoughts and to peacefully and democratically fight for their realization, allow for freedom of expression and association, the free and democratic election of all public officials and full access to the Internet. This process of democratization would allow all Cubans of good will to take part in the building of a democratic future of peace, justice and harmony, with everyone and for everyone’s benefit, regardless of their political views, religion, skin color or sexual orientation. Let’s hope open debate and the interests of the people prevail over the petty interests of extremists. Socialism in defense of life.