Ted Piccione, Brookings Institute, April 16, 2018.

Original Article: About to Get Worse

Ted Piccone Senior Fellow – Foreign Policy, Latin America Initiative, Project on International Order and Strategy

The orchestrated presidential succession underway this week in Cuba, from Raúl Castro to his likely replacement Miguel Díaz-Canel, is prompting a new round of speculation about how the Trump administration should react to the long-awaited departure of the Castro brothers from power. Judging from the heated rhetoric between the U.S. and Cuban delegations at last week’s Summit of the Americas, relations are likely to go from bad to worse.

Shortly before the U.S. presidential election, candidate Donald Trump promised to “cancel” President Obama’s normalization policy. His administration made good on that promise last year with a number of measures rolling back key features of the incipient rapprochement. This included dire travel warnings, a dramatic 60 percent drawdown of U.S. embassy personnel in Havana, and the eviction of 17 staff from Cuba’s embassy in Washington last September in response to unexplained health incidents affecting U.S. diplomats.

These steps loudly signaled the return of Florida’s pro-embargo faction, led by Senator Marco Rubio, at the helm of U.S.-Cuba policy. Now, with the appointment of the more hardline John Bolton and Mike Pompeo to top national security positions, we should expect the White House to double down on its first year’s embrace of punitive regime change.

THE HANDCUFFS OF THE EMBARGO AND DOMESTIC POLITICS

Ever since the nearly six decades of hostilities between Havana and Washington began, the United States has been locked in a narrow band of policy options. Even after the fall of the Soviet Union, the engine driving U.S. strategy remained a deep distrust of Cuba’s closed socialist system, fueled by the hundreds of thousands of nostalgic Cuban exiles concentrated in the swing state of Florida. Domestic politics prevails.

The rationale for tightening or loosening the comprehensive embargo established in the Kennedy administration has shifted, depending on the circumstances. The pivotal moment, however, was Congress’ decision to codify the embargo after the Cuban military shot down a plane piloted by Cuban exiles in 1996. This law—with its unilateral demands for the end of communist rule, the removal of the Castros from power, the establishment of free and fair elections, and full respect for human rights—severely handicapped any attempt by U.S. policymakers to adapt to changing circumstances, let alone construct an alternate route toward reconciliation and change.

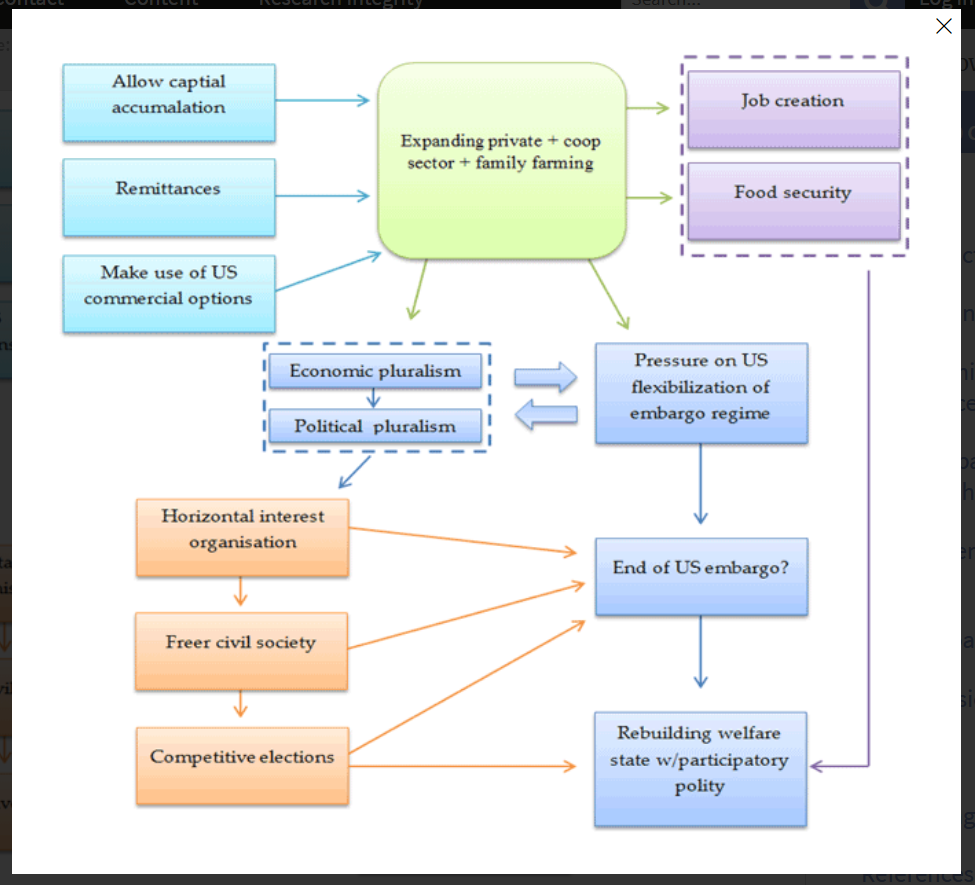

Until the Obama administration. For a short period of two years, it forged a narrow path between a rock and a hard place, encompassing diplomatic recognition, bilateral cooperation in areas of mutual interest, continued U.S. support for the Cuban people’s claim for more political and economic freedom, and a call for Congress to lift the embargo. Obama took these steps after the Raúl Castro government adopted concrete actions toward reform such as reducing the size of the bloated public sector, opening new avenues for private sector entrepreneurs, and expanding personal liberties for Cubans to buy and sell property, access the internet, and travel on and off the island more freely. These mutually reinforcing dynamics contributed to a flourishing of Cuba’s non-state sector, which grew from a registered 150,000 self-employed workers in 2008 to 580,000 in 2017. Record numbers of Americans began seeing for themselves the realities of Cuban socialism, including thousands of Cuban Americans each year.

Until the Obama administration. For a short period of two years, it forged a narrow path between a rock and a hard place, encompassing diplomatic recognition, bilateral cooperation in areas of mutual interest, continued U.S. support for the Cuban people’s claim for more political and economic freedom, and a call for Congress to lift the embargo. Obama took these steps after the Raúl Castro government adopted concrete actions toward reform such as reducing the size of the bloated public sector, opening new avenues for private sector entrepreneurs, and expanding personal liberties for Cubans to buy and sell property, access the internet, and travel on and off the island more freely. These mutually reinforcing dynamics contributed to a flourishing of Cuba’s non-state sector, which grew from a registered 150,000 self-employed workers in 2008 to 580,000 in 2017. Record numbers of Americans began seeing for themselves the realities of Cuban socialism, including thousands of Cuban Americans each year.

Whether or not one agrees with the Obama approach of constructive engagement, it took critics only a few months to declare it a bust for failing to force Cuba to adopt fundamental human rights and market economic reforms. This was, and remains, patently unrealistic. Some progress was made quickly: release of political prisoners; expanded cooperation on matters such as maritime security, drug trafficking, and counterterrorism; new commercial opportunities for American farmers and travel businesses; a significant drop in illegal immigration; and direct support to the Cuban private sector and religious communities.

Beyond these short-term gains, Obama’s strategic gambit was about laying the groundwork for long-term change, especially as a new generation of post-Castro leadership takes the helm this month. It was aimed at removing the Cuban government’s ability to paint the United States as its mortal enemy, a narrative it has used effectively for decades to consolidate its standing at home and around the world. It was also designed to build bridges for dialogue and reconciliation among Cubans on and off the island, which is at the heart of the problem, and triggered a flood of new exchanges and record levels of remittances to struggling Cuban families. Not surprisingly, large majorities in both countries applauded this new approach.

BOLTON, POMPEO, AND RUBIO

For the vocal constituency of Cuban exiles and their families, who bear bitter feelings toward the Castro regime, Obama’s March 2016 handshake with Raúl was sacrilege. They found, among the many Republicans who support their cause, a late convert in Donald Trump who, in the final stretch of his presidential campaign, hardened his position on Cuba, promising a crowd in Miami that he would reverse Obama’s executive orders “unless the Castro regime meets our demands.” The following June, surrounded by veterans of the failed Bay of Pigs operation in the heart of Miami’s Little Havana, President Trump delivered a theatrical rebuke of Obama’s opening toward Cuba and set in motion new rules to restrict individual travel and prohibit any dealings with Cuba’s leadership or military, police, and security officials and their business entities.

For Senator Rubio, the architect of Trump’s hardline approach toward Cuba, this tightening of the screws was not enough. The new rules, for example, allowed any previously negotiated business deals to remain intact, permitted air and cruise ship travel to continue, and kept Cuba off the state sponsors of terrorism list. (Obama’s authorization of unlimited travel and remittances for Cuban Americans, popular in Miami, notably went untouched.) When mysterious ailments affecting over 20 U.S. personnel were reported in the late summer of 2017, Rubio and his allies jumped on the opportunity to demand additional steps to punish the Cuban government for failing to prevent or explain the source of the incidents. Trump ordered diplomats in both countries to go home and issued severe travel warnings. The result: a dramatic reduction in the number of Americans visiting the island, and vice versa. This directly undermines the administration’s purported goal of supporting Cuba’s burgeoning private sector, which U.S. visitors help sustain.

Now, enter John Bolton and Mike Pompeo, stage right. Both have strongly criticized the Castro government and vociferously opposed Obama’s overtures to Havana. Bolton, who was roundly criticized in the 2000s for his unfounded allegation that Cuba was developing biological weapons, wroteas recently as January that “Russian meddling in Latin America could inspire Trump to reassert the Monroe Doctrine (another casualty of the Obama years) and stand up for Cuba’s beleaguered people (as he is now for Iran’s).” Given Russia’s expanding security and economic relationship with Havana, and the general hardening of U.S. policy toward Moscow, this is no longer an abstract notion. Bolton also doubted whether the Cuban regime can survive much longer, a perennial claim used to justify more punitive sanctions, despite Cuba’s ability to withstand five decades of the U.S. embargo, threats, attacks, and assassination attempts.

Pompeo, who initially endorsed Marco Rubio for president, was highly critical of Obama’s visit to the island in 2016 and defended retaining the U.S. detention facility at Guantanamo Bay. Although his Senate confirmation testimony on April 12 promised to improve relations with Cuba and rebuild diplomatic staff, Pompeo made no specific commitments on how or when this would occur.

We should expect a continued mind meld among these three key actors in the U.S.-Cuban drama. Senator Rubio, with colleagues from the Florida delegation, has already called on the White House to “denounce Castro’s successor as illegitimate in the absence of free, fair, and multiparty elections, and call upon the international community to support the right of the Cuban people to decide their future.” Rubio then traveled to the Summit of the Americas in Lima with Vice President Pence, who declared Cuba “a despotic regime” and blamed it for exporting its “failed ideology” to Venezuela and beyond. In response, Cuban Foreign Minister Bruno Rodríguez harshly attacked both Pence and Rubio for decades of “U.S. imperialism,” denounced U.S. political corruption, and blamed the Miami “mafia” for hiding terrorists. Not surprisingly, the region remains divided on how to respond.

From a national security perspective, it is hard to understand why Cuba occupies so much high-level attention, given the much more serious security challenges Washington faces. Cuba can barely keep its armed forces trained and equipped, and is falling short on many economic and social fronts as well, prompting thousands of Cubans to vote with their feet every year and risk the perilous journey to the United States or elsewhere. The deterioration in relations also adds pressure on Cuba to turn to Moscow and Beijing for more help, a prospect that directly runs counter to U.S. interests.

In the end, what matters most to this administration is the power many of those same Cubans wield by supporting politicians who want the total collapse of the Cuban regime. The Bolton-Pompeo-Rubio triangle, hand in hand with Trump and Pence, will gladly meet their needs, and then some.

@marcorubio

@marcorubio