El Toque Feb 10, 2021

Complete Listing: from El Toque

Complete listing in PDF format

……..

………………

…………………………..

……………………………………………

…………………………

……………

………

El Toque Feb 10, 2021

Complete Listing: from El Toque

Complete listing in PDF format

SIN UNA REFORMA FINANCIERA QUE SE HAGA ACOMPAÑAR DE UNA REFORMA PRODUCTIVA SERIA, VA A SER DIFÍCIL SALIR DE LA CRISIS POR LA QUE CUBA ATRAVIESA.

Omar Everleny Pérez Villanueva, noviembre 19, 2019

Corrían los primeros años de la década del 90 del siglo pasado y Cuba se adentraba en el llamado Período Especial en Tiempo de Paz. Para resistir y salir de la profunda crisis, las autoridades cubanas, especialmente Fidel Castro, anunciaban que se priorizarían las inversiones en determinados sectores estratégicos, entre ellos el turismo y la biotecnología.

Pero ambos requerían una importante inversión y demorarían en dar ingresos. Había entonces que buscar algún modo de captar divisas de manera más veloz. Y ahí apareció, en 1993, la despenalización de la tenencia de divisas extranjeras y la autorización para que la población adquiriera en tiendas en divisas los productos necesarios que ya estaban en falta en el circuito de ventas en moneda nacional (CUP). Se explicó que había mucha gente con divisas en su poder y que, simplemente, se estaba legalizando lo que ya era una realidad. Pero la motivación de recaudar divisas procedentes de las ayudas familiares tampoco se ocultaba.

Paralelamente, surgieron las Casas de Cambio, conocidas como CADECA, especialmente para que una parte de la población pudiese canjear las divisas que le habían enviado, adquirir CUP y así combatir el mercado negro en divisas. En aquel entonces, para hacer compras en las tiendas de divisas no era necesario canjearlas en CADECA por CUC. En las tiendas minoristas circulaba libremente el dólar, y más tarde hasta el euro en algunos polos turísticos. Durante esa época también se autorizó la posibilidad de abrir cuentas en divisas en bancos cubanos.

Paralelamente, surgieron las Casas de Cambio, conocidas como CADECA, especialmente para que una parte de la población pudiese canjear las divisas que le habían enviado, adquirir CUP y así combatir el mercado negro en divisas. En aquel entonces, para hacer compras en las tiendas de divisas no era necesario canjearlas en CADECA por CUC. En las tiendas minoristas circulaba libremente el dólar, y más tarde hasta el euro en algunos polos turísticos. Durante esa época también se autorizó la posibilidad de abrir cuentas en divisas en bancos cubanos.

En Cuba había un referente de la existencia de tiendas en divisas, en las que solamente podían comprar los visitantes extranjeros: las tiendas en los hoteles conocidas como tiendas Caracol, aunque existían otras como Cubalse. También antes de los años 90 existieron billetes que permitían comprar en esas tiendas. Eran de diferentes colores: los había carmelitas, que recibían los estudiantes extranjeros en Cuba, o rojos para quienes estaban autorizados a estar en el extranjero por misiones o estudiando, entre otros. Se canjeaban en algunos bancos, sobre todo en el Banco Financiero Internacional (BFI): se entregaba la moneda extranjera y a uno le devolvían esos bonos.

Continuar: LAS TIENDAS RECAUDADORAS DE DIVISAS EN CUBA Y SUS ASPIRACIONES

Tuesday, July 31, 2018

Just three months after Miguel Diaz-Canel took over the presidency of Cuba from Raul Castro, his government has unveiled a new Council of Ministers—essentially, Cuba’s Cabinet—along with the draft of a new constitution and sweeping new regulations on the island’s emergent private sector. While the changes announced represent continuity with the basic reform program Raul Castro laid out during his tenure, they are nevertheless significant milestones along the road to a more market-oriented socialist system.

The discussion and approval of the draft constitution was the main event of last week’s National Assembly meeting. The revised charter will now be circulated for public debate, revised, reconsidered by the National Assembly, and then submitted to voters in a referendum early next year. The avowed reason for revamping the constitution is to align it with the economic reforms spelled out in 2011 and 2016 that constitute the blueprint for Cuba’s transition to market socialism. Cuba’s 1976 constitution, adopted at the height of its adherence to a Soviet model of central planning, reflected “historical circumstances, and social and economic conditions, which have changed with the passing of time,” as Raul Castro explained two years ago. …

Continue Reading: Is Cubas Vision of Market Socialism Sustainable_

HAVANA TIMES, Junio 16, 2017 | | | 0 38 0 38

En Cuba alquilar un coche, dormir en un hotel, hacer submarinismo o comprar en una tienda tienen un punto en común: las empresas que dan esos servicios pertenecen al Grupo de Administración Empresarial S.A. (GAESA) dirigido por las Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias, reportó dpa.

GAESA es el mayor holding cubano y suma un conglomerado de más de 50 empresas, todo ello dirigido bajo las leyes del mercado y presidido por el general de brigada Luis Alberto Rodríguez López-Callejas, ex yerno del mandatario Raúl Castro.

La compañía más conocida es la cadena hotelera Gaviota, que tiene más de 29.000 habitaciones en todo el país, muchas de ellas en gestión compartida con compañías extranjeras como Meliá, Iberostar o incluso la estadounidense Starwood, de la cadena Marriott.

La joya de la corona de GAESA es el sector turístico, con una cuota de mercado del 40 por ciento, pero este conglomerado es mucho más amplio de lo que muchos piensan, llegando a casi todos los sectores de la economía, siempre y cuando den beneficios.

Luis Alberto Rodríguez López-Callejas

GAESA es propietaria de una naviera, tiene su propia compañía aérea, empresas de construcción, venta de automóviles, inmobiliarias, bancos o la empresa Almacenes Universales S.A., que controla el tráfico de contenedores en el Puerto del Mariel con su Zona Especial de Desarrollo, la gran apuesta del Gobierno cubano para atraer inversiones extranjeras a la isla gracias a los beneficios fiscales.

En sus inicios, el Ministerio del Interior y el de las Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias tenían sus propias empresas, separadas unas de otras, para autofinanciar sus actividades diarias. Asegurar a cada institución una parte del pastel económico garantizaba una paz entre ellas.

El equilibrio existió hasta 2010, cuando CIMEX, el mayor conglomerado comercial de la isla fundado por el Ministerio del Interior, fue absorbido por los militares, con lo que estos aumentaron sus cadenas de tiendas, pero sobre todo los servicios financieros y la capacidad de importación y exportación.

El imperio GAESA aumentó el año pasado con la adquisición de Habaguanex, la compañía que gestiona las empresas turísticas del casco histórico de La Habana Vieja y hasta entonces en manos del poderoso historiador Eusebio Leal.

La otra absorción fue la del Banco Financiero Internacional (BFI), la principal entidad de su tipo para la gestión de divisas. Ambas adquisiciones hicieron que GAESA continuase copando sectores económicos altamente rentables por su relación con el mercado exterior.

El envío de remesas a Cuba está monopolizado por su Financiera Cimex (Fincimex), que tiene acuerdos con empresas como Western Union.

También Fincimex controla en la isla los procesamientos de las tarjetas internacionales Visa y Mastercard.

Estas alianzas financieras internacionales están ligadas también al sector turístico, porque es vía Fincimex que las empresas que envían remesas pagan en Cuba a los dueños de casas y apartamentos que utilizan los servicios de la compañía estadounidense Airbnb, especializada en alquiler de habitaciones.

Kempinski Hotel, Gaviota’s Newest Five-Star Hotel.

Presented at Florida International University, Cuban Research Institute Conference: “Beyond Perpetual Antagonism: Re-imagining U.S. – Cuba Relations.”

February 24, 2017

BY PAUL HARE

In Cuba Today, August 29, 2016

Original Essay: BAD NEWS FOR NEW IDEAS IN CUBA

Havana historian Eusebio Leal escorts U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry around Old Havana during a tour of the city last year. Ismael Francisco AP

Very few without Castro in their name have survived in the leadership of the Cuban Revolution as long as Eusebio Leal. And he didn’t do it by the conventional means of silence and obedience. He brought loyalty but also ideas to the Castros. Now the military-run business empire has asserted itself in Old Havana as elsewhere and Leal appears to have been outmaneuvered.

Uniquely among Cuban leaders Leal has cared about other things beyond preserving the Castro Revolution. He has been as fascinated by Cuba’s past as its future. He has received numerous overseas cultural awards but his stature in Cuba has been that he thought differently.

In 2002 the British embassy in Havana staged a two-month-long series of events to commemorate 100 years of diplomatic relations between Cuba and the United Kingdom. We were told it was the largest such festival by an overseas country ever held in Cuba. Leal was our indispensable ally for venues, organization, contacts and vision. At times the Revolution’s agenda surfaced and he negotiated hard. But his heart was in the history of both our countries. Leal even created a garden in Old Havana in memory of Princess Diana. And as a historian he loved the story of the British invasion of Havana in 1762.

The military conglomerate GAESA will now assume business control over Leal’s beloved Old Havana project. This has been a labor of love and ingenuity. But it has also depended on his versatile role at the heart of revolutionary politics. He proved a man of taste, of determination but also shone as a contemporary entrepreneur in a Cuba which despises individualism.

His versatility served him well. A teenager at the time of the Revolution, he chose to prove that innovation and a love of past cultures and elegance could coexist with the new era. He admired Fidel, a fellow intellectual, and — not accidentally — he was chosen by the official Cuban media to eulogize his old friend again on his 90th birthday. Typically, the Revolution was extracting a declaration of loyalty from a man who was feeling pretty disgruntled.

Times are changing in Cuba and the undermining of Leal’s control has wider implications.

Times are changing in Cuba and the undermining of Leal’s control has wider implications. He may not be a household name outside Cuba and he may be in failing health. But his project showed he knew the Castros would never allow private sector growth to restore the largest area of Spanish colonial architecture in the Western Hemisphere.

His only chance was to harness funds from tourist visitors and foreign investors. There is still much to do but the current rush of tourists to Cuba owes much to achievement.

Leal’s fate is nothing new. Set in the 57-year context of the Cuban Revolution, many able and loyal leaders have been discarded. Felipe Pérez Roque, Carlos Lage and Roberto Robaina are recent examples. But Leal had survived and appeared to be growing in stature with Raúl. His walking tour of Old Havana with Obama received worldwide publicity.

Leal’s bonding with the U.S. president may have irked the Castros. The disintegration of Venezuela and loss of subsidies under Nicolás Maduro gave the military companies the opening they needed to swoop for Old Havana. Now, effectively Raúl Castro’s son-in-law will rule the roost and U.S.-operated cruise ships will soon be occupying many berths in the Old Havana harbor.

But perhaps the saddest lesson from Leal’s marginalization is the signal it sends to Cuban innovators and foreign investors. The restoration of the Revolution is still more important than the architectural jewels of past eras. Almost at the same time as Leal’s demise, a far less visionary but unquestioning loyalist, Ricardo Cabrisas, was promoted. These are indeed depressing times for Cubans hoping for some new ideas and less of the same.

Dr. Eusebio Leal Spengler, Historiador de La Habana

Dr. Eusebio Leal Spengler, Historiador de La Habana

Paul W. Hare is a former British ambassador to Cuba and currently senior lecturer at the Frederick S. Pardee School of Global Studies at Boston University

Archibald Ritter

February 1, 2016

Since 2010, Cuba has been implementing a redesigned institutional structure of its economy. At this time it is unclear what Cuba’s future mixed economy will look like. However, we can be sure that it will continue to evolve in the near, medium and longer term. A variety of institutional structures are possible in the future and there are a number of types of private sector that Cuba could adopt. Indeed it seems as though Cuba were moving towards a number of possibilities simultaneously.

The objective of this note is to examine a number of key institutional alternatives and weigh the relative advantages and disadvantages for each arrangement. All alternatives include some mixture of domestic or indigenous private enterprises, cooperative and “not-for-profit” activities. foreign enterprise on a joint venture or stand-alone basis, some state enterprises (in natural monopolies for example) and a public sector. However, the emphasis on each of these components will vary depending on the policy choices of future Cuban governments.

The possible institutional structures to be examined here include:

1. Institutional status-quo as of 2016;

2. A mixed economy with intensified “cooperativization”;

3. A mixed economy, with private foreign and domestic oligopolies replacing the state oligopolies;

4. A mixed economy with an emphasis on indigenous small and medium enterprise.

Option 1. Institutional Status-Quo as of 2016

The institutional “status quo” is defined by the volumes of employment in the registered and unregistered segments of the small enterprise sector, the small farmer sector, the cooperative areas, the public sector, and the joint venture sector, plus independent arts and crafts and religious personnel. The employment numbers are mainly from the Anuario Estadístico de Cuba together with a number of guesstimates, some inspired by Richard Feinberg (2013). The guesstimate for unregistered employment in the small enterprise sector may seem exaggerated. However, a large proportion of the “cuentapropistas” utilize unregistered workers and a proportion of the underground economy does not seem to have surfaced into formally registered activities. These employment estimates by institutional area are presented in Table 1 and illustrated in Chart 1, which also serve as a “base case” for sketching the other institutional alternatives.

The current institutional status quo has a number of advantages but also some disadvantages. On the plus side, adhering to the status quo would avoid all the uncertainties and risks of a transition. It would maintain the possibility of “macro-flexibility,” that is the ability for the central government to reallocate resources by command in a rapid and large scale fashion. However, in view of the numerous “macro errors” made possible by a centralized command economy (the 10 million ton sugar harvest of 1970, the “New Man” endeavor, shutting down half the sugar mills), “macro-flexibility” may be a disadvantage. There are major advantages for the Communist Party in maintaining the institutional status quo in the economy, namely enabling political control of the citizenry (a disadvantage from other perspectives) and continuing state control over most of the distribution of income (also a disadvantage from other perspectives). The approach also helps foster good relations with North Korea (I am running out of advantages).

There are also major disadvantages. The centralized planned economy and public enterprise system generates continuing bureaucratization of production; continuing politicization of state-sector economic management and functioning; continuing lack of an effective price mechanism in the state sector and continuing perversity and dysfunctional of the incentive structure. The result of this is damage to efficiency, productivity and innovation.

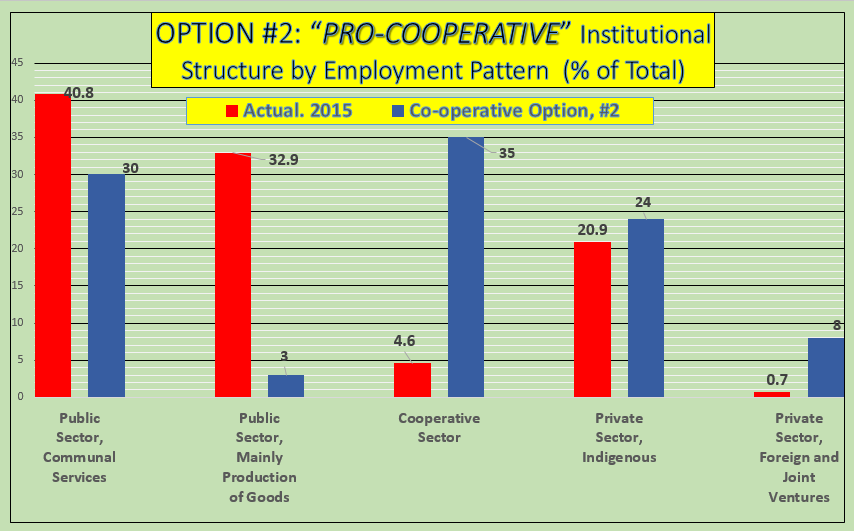

OPTION 2. Mixed Economy with Intensified “Cooperativization”

A second alternative might be to promote the authentic “cooperativization” of the economy in a major way. This would involve permitting cooperatives in all areas, including professional activities; opening up the current approval processes; encouraging grass-roots bottom-up ventures; providing import & export rights; and improving credit and wholesaling systems for coops.

A second alternative might be to promote the authentic “cooperativization” of the economy in a major way. This would involve permitting cooperatives in all areas, including professional activities; opening up the current approval processes; encouraging grass-roots bottom-up ventures; providing import & export rights; and improving credit and wholesaling systems for coops.

This approach has a number of advantages. First, it would strengthen the incentive structure and elicit serious work effort and creativity on the part of those in the coops. This is because worker ownership and management provides powerful motivation to work hard and profit-sharing ensures an alignment of worker and owner interests. This approach would generate a more egalitarian distribution of income than privately-owned enterprises. Cooperatives may possess a greater degree of flexibility than state and even private firms because their income and profits payments to members can reflect market conditions. Perhaps most important, democracy in the work-place through effective and genuine coops is valuable in itself and constitutes an advantage over both state- and privately-owned enterprise. [Workers’ ownership and control proposed in Cuba’s cooperative legislation is ironic and perhaps impossible since Cuba’s political system is characterized by a one-party monopoly. On the other hand it may help propel political democratization.]

The “second degree cooperatives” or “cooperative coalition of cooperatives” called for in the cooperative legislation is particularly interesting as it may permit reaping organizational economies of scale (a la Starbucks, McDonalds, etc. ) for small Cuban coops in these areas.

An emphasis on cooperatives would help to maintain ownership and diffused control and profit-sharing among local citizens, thereby promoting greater equity in income distribution.

But cooperatives also face difficulties and disadvantages. First, are they really more efficient than state and private enterprises? Generally speaking, cooperatives have passed the “survival test” but have not made huge inroads against private enterprise in other countries over the years. Perhaps this is because the “transactions costs” of participatory management may be significant. Personal animosities, ideological or political differences, participatory failures and/or managerial mistakes may occur. And for larger coops, complex governance structures may impair flexibility.

Second, Cuba’s actual complex co-op approval process is problematic and creates the possibility of political controls and biases. Certification of professional cooperatives is unclear. Also, the hiring of contractual workers is problematic

Finally, what will be the role of the Communist Party in the cooperatives? Will it keep out of cooperative management? Will Party control subvert workers’ democracy and deform incentives structures?

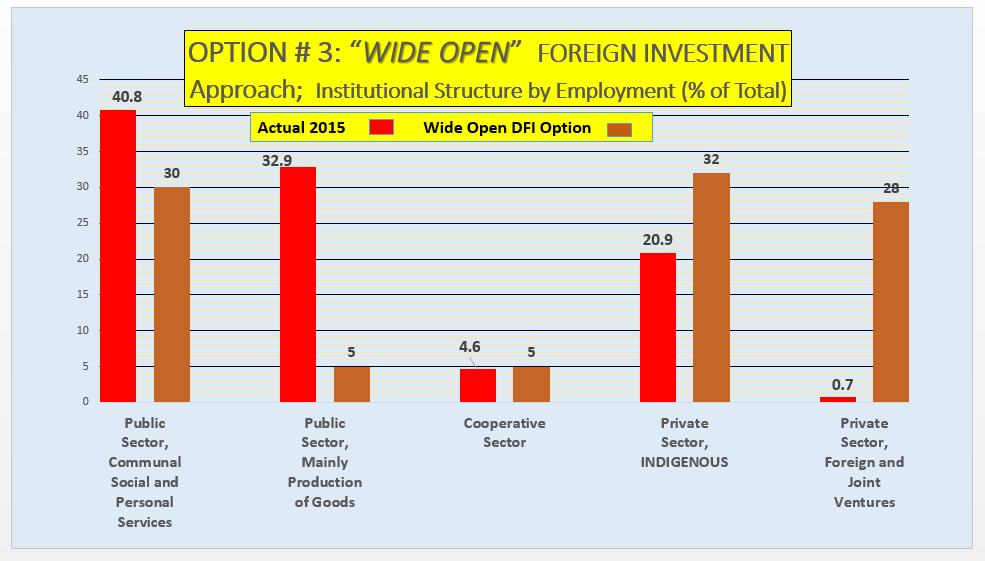

OPTION 3. Wide Open Foreign Investment Approach  A third possibility would be to open up completely to foreign investment. This would involve a rapid sell-off of state oligopolistic enterprises to deep-pocket foreign buyers such as China, the United States (in due course), Europe, Brazil, or elsewhere. The buyers might be the Walmart’s, Lowes, Subways, or Starbucks of this world, wanting to acquire major access to the Cuban market. This is a strong possibility if existing state oligopolies (e.g., CIMEX and Gaviota) were to be privatized in big chunks. The policy requirements for this approach to occur would be rapid privatization plus indiscriminate direct foreign investment and takeovers by large foreign firms.

A third possibility would be to open up completely to foreign investment. This would involve a rapid sell-off of state oligopolistic enterprises to deep-pocket foreign buyers such as China, the United States (in due course), Europe, Brazil, or elsewhere. The buyers might be the Walmart’s, Lowes, Subways, or Starbucks of this world, wanting to acquire major access to the Cuban market. This is a strong possibility if existing state oligopolies (e.g., CIMEX and Gaviota) were to be privatized in big chunks. The policy requirements for this approach to occur would be rapid privatization plus indiscriminate direct foreign investment and takeovers by large foreign firms.

This approach does have some advantages.

However, there would also be disadvantages such as:

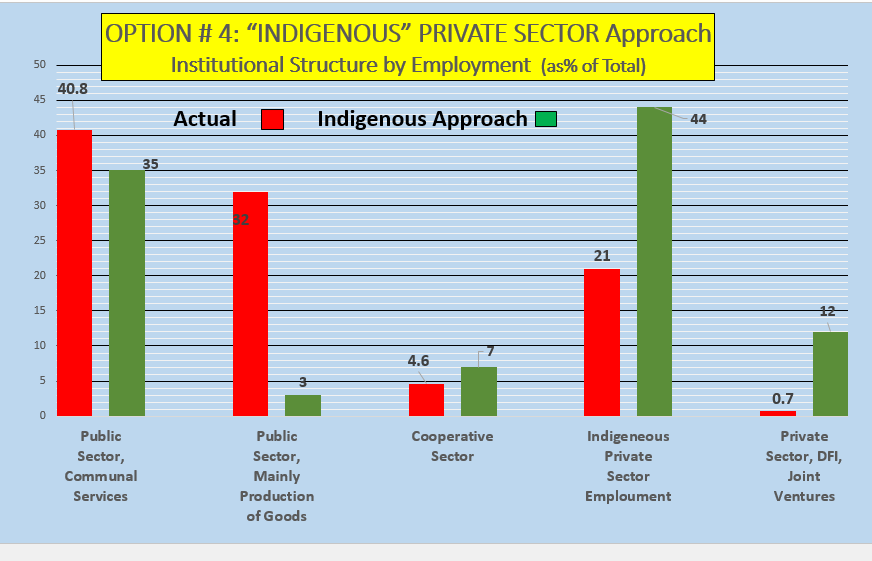

OPTION 4: Pro-Indigenous Private Sector in a Mixed Economy

A fourth possibility would be for Cuba to promote its own small-, medium- and larger enterprises in an open mixed economy. This would require

A fourth possibility would be for Cuba to promote its own small-, medium- and larger enterprises in an open mixed economy. This would require

A liberalization of micro-, small and medium enterprise would also be necessary to release the creativity, energy and intelligence of Cuban citizens. This would involve open and automatic licensing for professional enterprises; an opening up for all areas for enterprise – not only the “201”; permission for firms to expand to 50 + employees in all areas; creation of wholesale markets for inputs; open access to foreign exchange and imported inputs; full legalization of “intermediaries” ; and permission for advertising.

This approach has some major advantages:

Oligopoly power would be more curtailed compared to Option 3;

There would be some disadvantages with this approach.

Conclusion

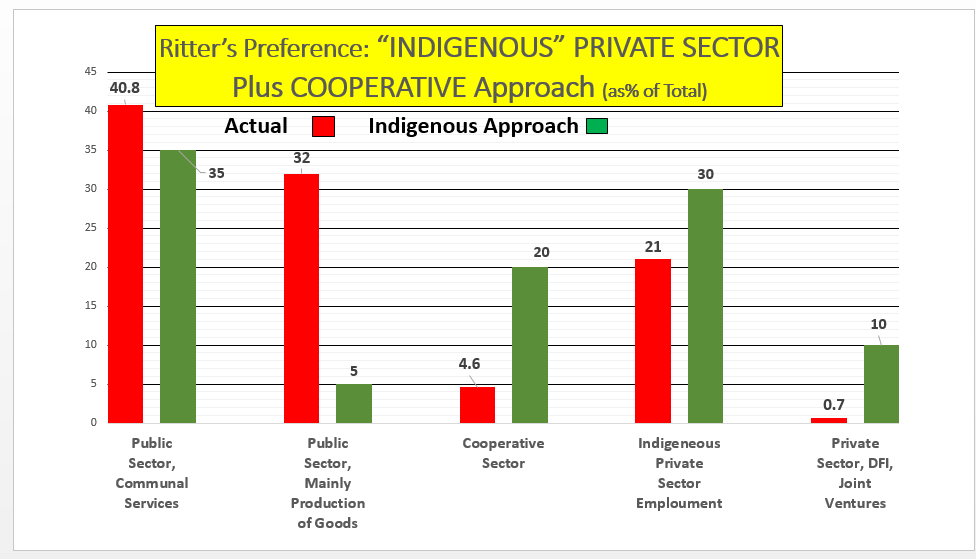

Most likely, Cuban policy-makers in the government of Raúl Castro, the government of his immediate successor, and future governments of a politically pluralistic character will design policies that ultimately will lead to some hybrid mixture of the above four possibilities. I of course will have little or no say in the process. However, my personal preference would be for an economy resembling the structure in the accompanying chart, with a large “indigenous” private sector, a significant cooperative sector, of course a large public sector for the provision of public goods, a small sector of government-owned enterprises, and a significant private foreign and joint venture sector.  So my bottom-line recommendations for current and future governments of Cuba would be:

So my bottom-line recommendations for current and future governments of Cuba would be:

Bibliography

Feinberg, Richard E., Cuba’s Economic Change in Comparative Perspective, Brookings Institution, 2013

Oficina Nacional de Estadísticas, Anuario Estadístico de Cuba, 2014

Ritter, Archibald and Ted Henken, Entrepreneurial Cuba, The Changing Policy landscape, Boulder Colorado: Lynn Rienner, 2015

By Emilio Morales and translated by Joseph L. Scarpaci, Miami (The Havana Consulting Group).

Original Article here: The Havana Consulting Group, Joint Ventures

There is a longing in Cuba for the ‘old days’ of the 1990s when there was a successful boom in creating joint-venture companies on the island. Such nostalgia stems from the economic and political crisis in Venezuela, which has lessened the flow of capital from Big-Brother Venezuela.

Joint-venture companies played a key role in helping the Cuban economy recovery in the 1990s when Soviet aid dried up and the so-called Special Period began.

Many of these companies supported the expanding tourist sector and the decriminalization of the U.S. dollar, which became a staple in a dollarized retail market.

This spate of joint ventures sought to develop tourism infrastructure, assist in import substitution, and revive the national economy.

Joint venture companies concentrated mainly in the industrial sector, tourism, food processing, and real estate. Assuming there was a prior agreement with the Cuban counterpart, decisions were usually made by the foreign partner because they had put up the capital and the know-how.

In this stage of the island’s history with joint ventures, foreign companies played a key role training personnel about modern marketing research methods. This was a time when the economic teams of the armed forces launched the so-called ‘business improvement’ (perfeccionamiento empresarial in Spanish) programs.

Upper management teams of these companies learned modern marketing research techniques. Training this echelon of Cuban businessmen and women was a way to ensure loyalty, avoid corruption, and safeguard information.

Some $3 billion drove this surge of joint-venture operations and parallel activities in duty-free zones.

Uncertainty lowers the expectations of reforms.

Around 2002, the number of joint ventures and amount of investment capital began declining. Two years later, the government did an about-face and began centralizing the economy once again which, in turn, caused investment to dry up and erode the economic reforms launched in the 1990s.

As a result, some 200 joint-venture operations folded and investment plummeted. The Cuban government took to prioritizing investments with such friendly nations as Venezuela, China and Brazil to fill this investment void, offering private investors slim pickings.

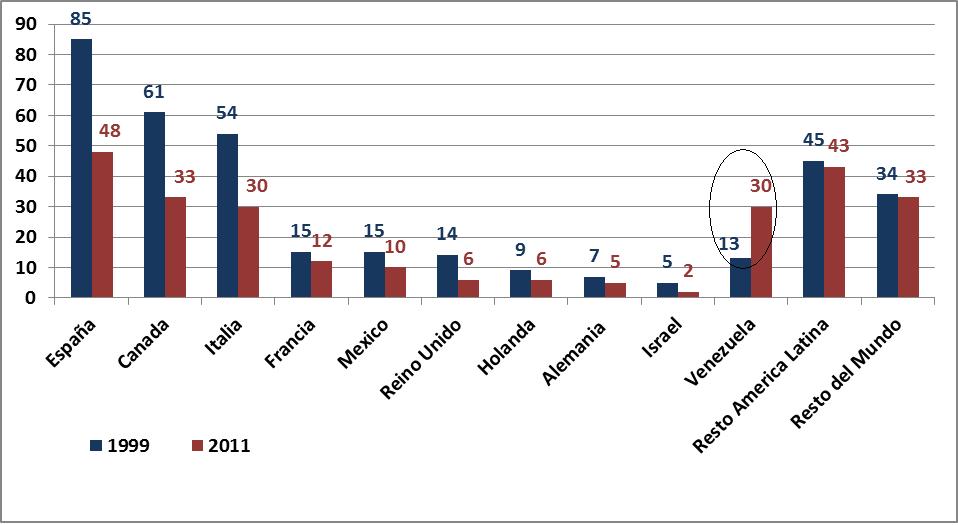

Investment and joint-venture operations dropped off quickly between 1999 and 2011, except in Venezuela, where they shot up from 13 to 30.

Figure 1. Number of Businesses Operating in Foreign Direct Investment, 1999-2001.

Data source: Ministry of Foreign Investment and Collaboration (1999) and the Ministry of Foreign Trade and Foreign Investment (2001, calculated by The Havana Consulting Group.

Those foreign companies that remained in Cuba during this period had to endure, from 2008 to 2010, diminished or no payments that were owed to them by the island’s government (called the corralito, or little corral). Considerable tension resulted, particularly between the Spanish diplomatic corps that pleaded for payment to some 300 Spanish firms who had operations there.

This acute two-year financial crisis stemmed from the island’s lack of liquidity that not only affected the supply of raw materials in the sectors where these foreign firms operated, but decreased inventory in hard-currency retail chains and in tourism. The Cuban government’s failure to make payments led to a further decline in foreign investment as investors got jittery.

Raúl Castro introduced a series of economic reforms called “updating the Cuban economic model” when he came to power. This entailed trying to insert market mechanisms at all levels of the economy with the socialist planning system. Joint ventures were at the center of these measures so that the economy could receive foreign investment. In all instances, the Cuban government maintains at least 51% control of these companies.

From the start of these reforms until October 2013, the bulk of them have tried to expand the private sector and agriculture. However, the pace of foreign investment has not gone as expected because of corruption charges made against some foreign investors residing on the island, and Cuban business representatives of joint-venture firms.

Cuban authorities have detained or jailed several foreign businessmen and high-ranking Cuban officials (including one minister and several vice ministers and Cuban CEOs. They are charged with corruption, bribery, and related crimes. Some have been sentenced up to 10 years while others were acquitted after having spent more than a year in jail while awaiting trial.

Undoubtedly, this anticorruption has proven unattractive to foreign investors because of the uncertainty and insecurity the matter has created.

Searching for investors.

Despite all this, the Cuban government has created a special zone adjacent to the Mariel port, just west of Havana. The Brazilian government has invested $900 million, which the Cuban government hopes will attract foreign investment and give the economy a second chance.

By the looks of things, the Cuban government is moving forward with plans to attract investment. It is noteworthy that Venezuela, its principle political ally and one of two pillars of the Cuban economy, is coping with a deep crisis back home. Still, these strategic actions aim to exceed the results obtained in the 1990s.

Potential gains in joint ventures will likely concentrate in the tourism, agriculture and real-estate sectors.

However, it is unclear whether the traditional business partners already located on the island will play a prominent role. The lack of transparency about the jailing of foreign businessmen and the closing of joint ventures is unattractive to international investors.

If we consider the recent announcement about shifting to a single currency, it is obvious that foreign companies with investments in Cuba take a beating. Government efforts to attract a new wave of investors to the new Mariel port facilities could be impacted adversely because of these proposed monetary changes.

Another weakness is the lack of flexible and attractive foreign investment laws.

This is why the government urgently seeks a new wave of foreign investors. To do that, it has announced that it is reworking its investment laws so that they appeal to the international community. Moreover, for the first time in half a century, these new laws may consider allowing Cubans who reside off the island to invest.

Until now, however, these new laws have not appeared. Until they do, uncertainty grows, the crisis deepens, and the country is losing the glamour and allure it needs to attract new investment.

Hotel Melia Cohiba, Spanish-Cuban Joint Venture

Hotel Melia Cohiba, Spanish-Cuban Joint Venture

Sherritt International Nickel Refinery, Fort Saskatchewan Alberta: Cuban-Canadian Joint Venture in Canada!

Sherritt International Nickel Refinery, Fort Saskatchewan Alberta: Cuban-Canadian Joint Venture in Canada!

The complete document is available here: Omar Everleny Pérez Villanueva, The Current Deregulation of Cuban Enterprises. Oct. 3 2013

Introduction

We cannot examine the last 50 years of Cuban economic activity without casting a critical eye. Even if we are clear about future goals, which are certainly full of challenges, an awareness of the pitfalls, errors, mistakes and misunderstandings from the past period may help to correct the future perspective.

Cuba is undergoing changes directed at achieving efficiency and increasing the productivity of the state-run enterprises (the plan), where efficiency depends, among other factors, on productivity. Productivity can be increased from different sources, but the important factor is that although a company may be proactive in the search for solutions, it is not possible to be proactive while being heavily regulated.

Various academic analyses show a decrease in the majority of state-owned economic sectors in the last 20 years, between the early 90’s and 2010, as well as in virtually all sectors, with the exception of a few, such as telecommunications, mining and construction, sectors that have received a strong injection of foreign capital since the early 90’s. Another study on skilled labor force shows low motivation, due to unsatisfactory wages, few moral and material incentives, organizational problems, over-qualification and, of course, technical materials problems.1

……….

Concluding Comment

On January 29, 2012, at the closing of the First National Conference of the Communist Party, Raul Castro stated that:

“The only thing that can lead to the defeat of the revolution and socialism in Cuba would be our inability to eradicate the mistakes made in the 50 years since January 1, 1959 and those that we incur in the future.”

Following this thinking, it is clear that the challenges posed by the transformation at a relatively short term of the existing structural distortions in the Cuban economy. If we want Cuba to become a land of opportunities and to achieve a sustained increase in the standard of living for all Cubans, then the time to make such decisions is not very far away, and the measures to take must be more pragmatic than those taken under the current government. At the same time we cannot forget to take into consideration the harassment that Cuba is subject to in its external transactions by the U.S. government.

DR. OMAR EVERLENY PEREZ VILLANUEVA

Professor at the University of Havana. Former director of the Centro de Estudios de la Economia Cubana at the University of Havana. Doctorate in Economic Sciences of the University of Havana in 1998. Masters in Economic and International Relations from CIDE, AC Mexico City, Mexico in 1990. Bachelors in Economics from the University of Havana in 1984.

Dr. Perez Villanueva has presented at conferences in various Cuban institutes as well as internationally, including in the United States, Japan, France, Canada, Spain, Brazil, Puerto Rico, Mexico, Dominican Republic, Venezuela, China, Malaysia, Argentina, Peru, Jamaica, Barbados, Trinidad and Tobago and Norway. He has served as a visiting professor at Universities in the United States, Japan and France and has published over 70 research papers in a variety of areas of the Cuban and global economy.

Dr. Perez Villanueva has also published over 75 articles in publications and has co-authored several books in Cuba and abroad, including “Cuban Economy at the Start of the Twenty-First Century,” with Jorge Dominguez and Lorena Barberia (Harvard University. ISBN 0-674-01798-6, 2004), the second edition of “Reflections on the Cuban Economy” (Editorial Ciencias, Havana. ISBN 959-06-0839-6, 2006) and “Outlook fo the Cuban Economy I and II” (ISBN 978-959-303-004-5). His last book is “Fifty Years of the Cuban Economy” (Editorial Ciencias Sociales. Havana. ISBN 978-959-06-1239-8).