Just Published on Espacio Laical, Suplemento Digital No.132 / 16 de Junio 2011

Tomado de la sección Búsqueda (revista 3-2011) Hyperlink here:

The Sixth Congress of the Cuba’s Communist Party will likely be of immense importance for Cuba’s future. The ratification of the revised Lineamientos de la Política Económica y Social del Partido y la Revolución “by the National Assembly means that it is now politically correct to support, advocate and implement an ambitious reform agenda. By implication, it also is politically correct to draw the conclusion that a half century of economic experimentation with the lives of Cuban citizens was for the most part misguided, counterproductive, and unsustainable. Despite attempts to create an impression of historical continuity by referring to the “updating” of the economic model, the old approaches to economic management have been deeply discredited. The shifting climate of opinion regarding how the Cuban economy can best function has been certified as reasonable by the National Assembly. It now appears that a regression to old modes of economic operation is now highly improbable..

The economic future for Cuba clearly lies in a newly-rebalanced albeit vaguely-envisaged mixed market economy that will be the outcome of the various reforms that are slated to be implemented. This is a surprising reversal of fortunes. It also constitutes a vindication of the some of the views of the critics of past economic policies.

The “Lineamientos” represent an attempt by President Raul Castro to forge his own “legacy” and to emerge from the long shadow of his brother, as well as to set the Cuban economy on a new course. The ratification of the reform agenda represents a successful launch of the “legacy” project. President Raul Castro would indeed make a unique and valuable contribution to Cuba and its citizens were he to move Cuba definitively through dialogue and agreement among all Cubans towards a model that guarantees both economic and social rights as well as civil liberties and authentic democracy.

Are moves in these directions likely to happen? Not under current political circumstances. However, there are bottom-up pressures building and some official suggestions that movement towards political liberalization is not impossible. In the meantime, Raul’s de-centralizing, de-bureaucratizing and “market-liberalizing” reforms been launched. This is a good start for the construction of a positive independent “legacy.”

I. Cuba’s Economic Situation

In various speeches since 2006, Raul Castro has indicated that he recognizes the problems that Cuba confronts in terms of the production of agricultural and industrial goods and improvement of Cuba’s infrastructure (despite the ostensibly solid GDP performance from 2005 to 2009 before Cuba was hit by the international recession.) He is well aware of the central causal forces underlying weak Cuba’s economic vulnerabilities and weaknesses such as the unbalanced structure of the economy, the overburden of deadening rules and regulations and a sclerotic bureaucracy and the monetary and exchange rate pathologies and dysfunctional incentive environment that deform the energies and lives of Cuban citizens.

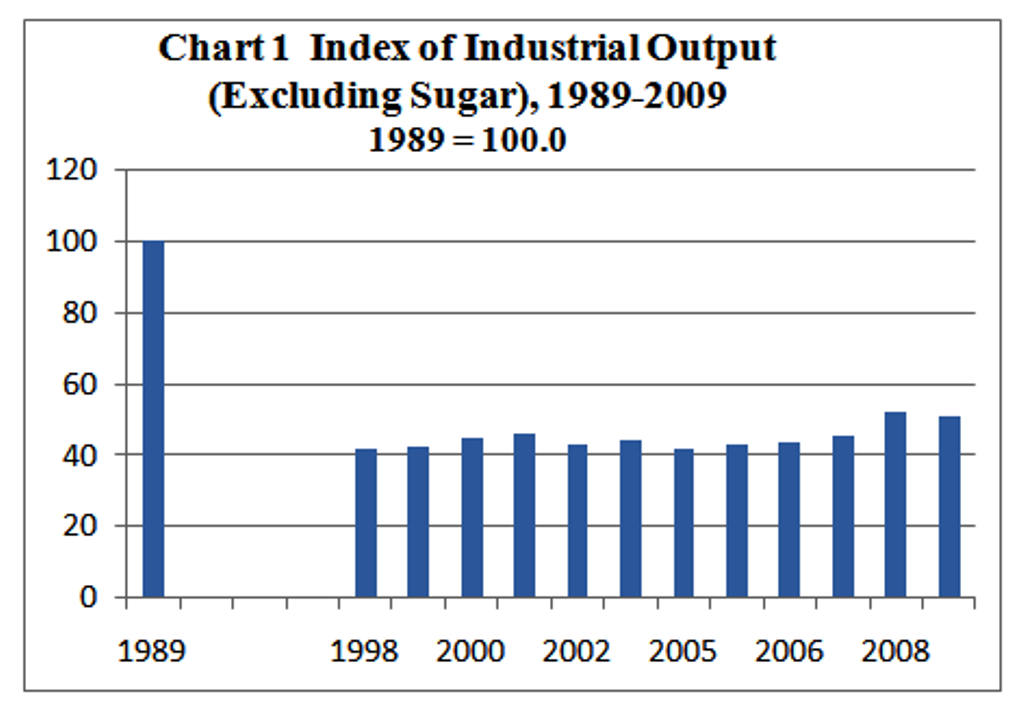

Cuba’s economic plight can be summarized quickly with a couple of illustrations. First, Cuba’s underwent serious de-industrialization after 1989 from which it has not recovered, reaching only about 51% of the 1989 level by 2009 (Chart 1)

Source: ONE AEC, 2004, Table 11.1 and 2IX.1

Source: ONE AEC, 2004, Table 11.1 and 2IX.1

Note: Data for 1990-1997 are not available

There are a variety of reasons for the collapse of the industrial sctor:

(a) The antiquated technological inheritance from the Soviet era as of 1989;

(b) Insufficient maintenance over a number of decades before and after 1989;

(c) The 1989-1993economic melt-down;

(d) Insufficient levels of investment; (The overall level of investment in Cuba in 2008 was 10.5% of GDP compared to 20.6% for all of Latin America according to UN ECLA, 2011, Table A-4.)

(e) The dual monetary and exchange rate system that penalizes potential exporters that would receive one old (Moneda Nacional) peso for each US dollar earned from exports;

(f) Competition in Cuba’s domestic market with China which has had a grossly undervalued exchange rate, coexisting with Cuba’s grossly overvalued exchange rate.

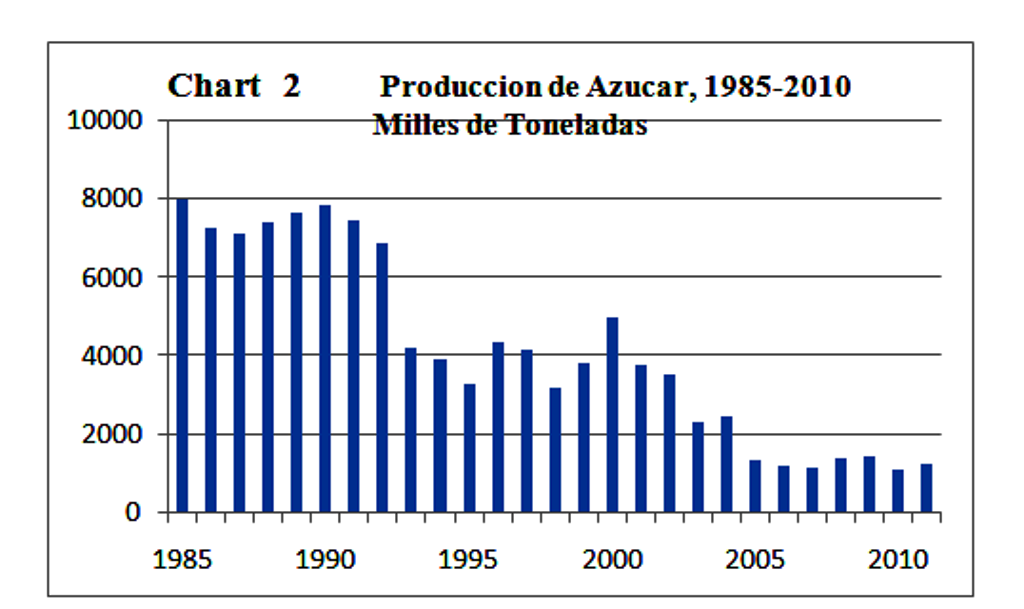

Second, the collapse of the sugar agro-industrial complex is well known and is illustrated in Chart 2. The sugar sector essentially was a “cash cow” milked to death for its foreign exchange earnings, by insufficient maintenance, by insufficient re-investment preventing productivity improvement, and by the exchange rate regime under which it labored.

Source: NU CEPAL, 2000 Cuadro A.86; ONE, 2010 Table 11.4

Source: NU CEPAL, 2000 Cuadro A.86; ONE, 2010 Table 11.4

The consequences of the collapse of the sugar sector include the loss of about US$ 3.5 billion in foreign exchange earnings foregone (generated largely with domestic value added); reductions in co-produced electricity; a large increase in idled farm land; a destruction of the capacity to produce ethanol; damaging regional and local development impacts, and a destruction of much of the “cluster” of input-providing, output-processing and marketing activities related to sugar.

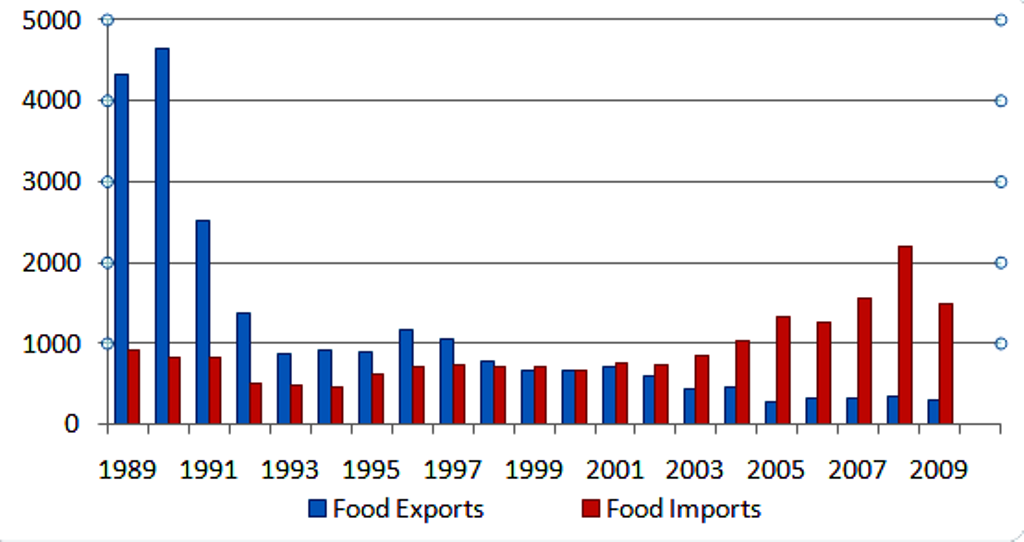

Third, the production of food for domestic consumption has been weak since 1989, despite some successes in urban agriculture. Food imports have increased steadily and in recent years account for an estimated 75 to 80% of domestic food consumption despite large amounts of unused farm land. Meanwhile agricultural exports have languished,

Chart 3 Cuban Exports and Imports of Foodstuffs, 1989-2009

(excluding Tobacco and Alcoholic Beverages) (Millions CUP)

Source: NU CEPAL, 2000 Tables A.36 and A.37, and ONE, AEC, Various Years.

Source: NU CEPAL, 2000 Tables A.36 and A.37, and ONE, AEC, Various Years.

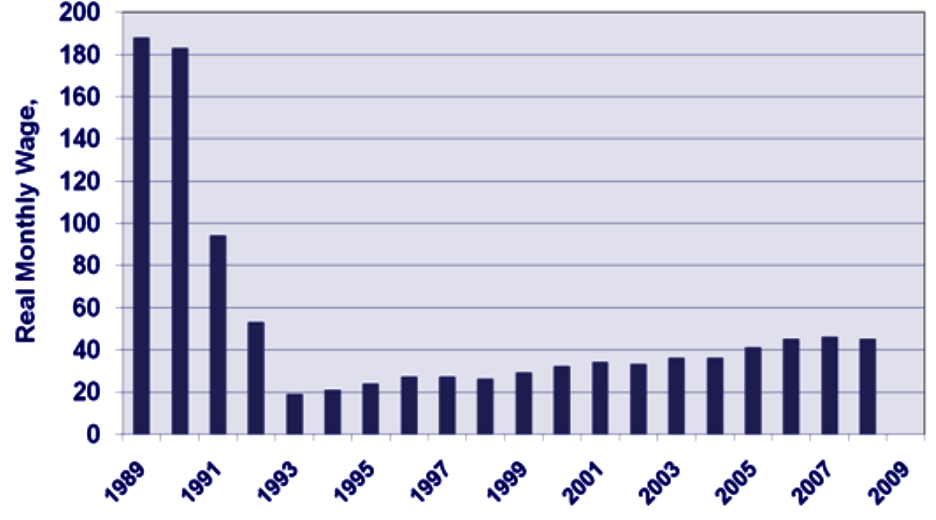

Fourthly, “inflation-adjusted “ or “real” wages in the official economy collapsed and have not recovered significantly according to estimates from the Centro de Estudios sobre la Economia Cubana (Chart 4.) This is indeed a major calamity for the official state economy. But though the official 2008 wage rate remained around 25% of its level of 1989, most people had other sources of income, such as remittances, legal self-employment, home produced goods and services, economic activities in the underground economy, income supplements in joint ventures, goods in kind from the state and widespread pilferage. Those without other sources of income are in poverty.

Chart 4 Cuba: Real Inflation-Adjusted Wages, 1989-2009

(Pesos, Moneda Nacional)

Vidal Alejandro, Pavel, “Politica Monetaria y Doble Moneda”, in Omar Everleny Perez et. al., Miradas a la Economia Cubana, La Habana: Editorial Caminos, 2009

Vidal Alejandro, Pavel, “Politica Monetaria y Doble Moneda”, in Omar Everleny Perez et. al., Miradas a la Economia Cubana, La Habana: Editorial Caminos, 2009

Furthermore, despite the exceedingly low official rates of unemployment – around 1.6 to 1.7%, (far below the “natural rate” of unemployment which represents normal new entrants, job-changers and structural changes in any economy) – underemployment is obviously very high. Presumably the 1.8 million workers considered by the Government to be redundant and subject to probable lay-off and transfer to small enterprise, are “underemployed”, accounting for around 35 per cent of the labor force.

A further dimension of the fragility of Cuba’s economic situation is the dependence on the special relationship with Venezuela that relies upon high oil prices and the presence and munificence of President Chavez.

It is to the credit of President Raul Castro that he has faced these problems directly, diagnosed their sources, and produced the “Lineamientos” to deal with them. The central sources of the difficulties are the general structure of incentives that orients the economic activities of Cuban citizens, this including the dual monetary and exchange rate system, the tight containment of individual economic initiatives, the detailed rules and regulations of the omnipresent bureaucracy. Paradoxically, in attempting to control everything in the past, the government has ended up controlling very little. The effectiveness of stricter state controls actually leads to weaker genuine control due to their promotion of illegalities, corruption and the ubiquitous violation of unrealistic regulations.

II. The Lineamientos

The objective of the “Lineamientos” is “to guarantee the continuity and irreversibility of Socialism” as well as economic development (p.10). This is to be achieved through an “up-dating” of the economic model that should result in utilization of idle lands, reversal of decapitalization of infrastructure and industry, a restructuring of employment, increased labor productivity, increased and diversified exports, decentralized decision-making and elimination of monetary and exchange rate dualism (p. 8.)

But the term “Socialism” remains somewhat ambiguous in the document. Reference is made to “socialist property” and “preserving the conquests of the Revolution.” Especially interesting is the statement that

“…socialism signifies equality of rights and equality of opportunities for all the citizens, not egalitarianism” (p.9)

This assertion could be of game-changing significance, as it articulates a fundamental principle of “Social Democracy” more so that a traditional principle of “Socialism.” This leaves questions unanswered and doors unclosed.

The “Lineamientos” are in effect an ambitions and comprehensive “wish-list” or statement of aspirations. Many of the 313 recommendations are fairly obvious, trite and general statements of reasonable economic management. Some statements have been made repeatedly over a number of decades, including those relating to the expansion and diversification of exports, science and technology policy, the sugar agro-industrial complex, or the development of by-products and derivatives from the sugar industry (an objective at least since 1950.) Restating many of these as guidelines can’t do much harm, but certainly does not guarantee their implementation.

There are also opaque elements among the guidelines and seeming contradictions as some of them stress continuity of state planning and control while others emphasize greater autonomy for enterprises. For example, Guideline 7 emphasizes how “planning” will include non-state forms of enterprise and “new methods…. of state control of the economy” while No. 62 states “The centralized character …of the degree of planning of the prices of products and services, which the state has an interest in regulating will be maintained.” But numerous other guidelines spell out the greater powers that state and non-state enterprises will have over a wide range of their activities including pricing (Guidelines 8 to 22 and 63.)

While there are a few gaps and shortcomings in the “Lineamientos” as well as the references to planning and state control, they include some deep-cutting proposals on various aspects of economic organization and policy that represent the inauguration of a movement towards a “market-friendly” economic policy environment. Among these are:

A central policy thrust is the expansion of the self-employment and cooperative sector in order to absorb ultimately some 1,800.000 state workers considered redundant. The legislation already implemented in October 2010 liberalized policy somewhat so as to encourage the establishment of additional microenterprises – especially by the liberalization of licensing, the establishment of wholesale markets for inputs and the recent relaxation of hiring restrictions. However, the limitations of the policy changes are highlighted by the modest increase in the number of “Paladar” chairs – from 12 to 20.

Unfortunately current restrictions will prevent the expected expansion of the sector. These include the heavy taxation that can exceed 100% of net earnings (after costs are deducted from revenues) for enterprises with high costs of production; the prohibition of the use of intermediaries and advertising, and continued petty restrictions. Perhaps most serious restriction is that all types of enterprises that are not specifically permitted are prohibited including virtually all professional activities. The 176 permitted activities, some defined very narrowly, contrast with the “Yellow Pages” of the telephone directory for Ottawa (half the size of Havana) that includes 883 varieties of activities, with 192 varieties for “Business Services”, 176 for “Home and Garden, 64 for “Automotive” and 29 for “Computer and Internet Services.” Presumably policies towards micro-and small enterprise will be further liberalized in the months ahead if laid-off workers are to be absorbed productively.

One short-coming of the “Lineamientos” is the lack a time dimension and a depiction of how the various changes will be implemented. There are no clear priorities among the innumerable guidelines, no sequences of actions, and no apparent coordination of the guidelines from the standpoint of their implementation. It remains a “check-list” of good intentions, though none-the-less valuable.

The absence of a vision of how change was to occur and the slow pace of the adoption of the reforms so far is also worrisome. However, the Administration of Raul Castro has been deliberative and systematic though also cautious. It is probable that somewhere in the government of Raul Castro there is a continually evolving time-line and master-plan for the implementation of the reform measures.

A careful and well-researched approach to economic reform is obviously desirable. The difficulties encountered in laying off 500,000 state sector workers and re-absorbing them in the small-enterprise sector by March 31, 2011 has probably encouraged an even more cautious “go-slow” approach. Perhaps “slow and steady wins the race!”

A process of economic —but not political— reform seems to have already begun following the Congress. Where it will lead is hard to predict. Presumably Raúl Castro’s regime would like the process to end with the political status quo plus a healthy economy. The latter would require a new balance between public and private sectors, with a controlled movement toward the market mechanism in price determination and the shaping of economic structures, and with the construction of a rational configuration of incentives shaping citizens’ daily economic actions so that their private endeavors become compatible with Cuba’s broader economic well-being.

In such a reform process many things would be changing simultaneously with symbiotic impacts and consequences that will likely be painful and are difficult to foresee. Will President Raul Castro have the courage to take the risks inherent in an ambitious process of economic change? This remains to be seen. But the economic and political consequences of inaction are so bleak and the attractiveness of a positive historical “legacy” are so enticing that President Raul Castro will continue.

The economic reform process has been launched. It is in its early stages. It will likely continue under the leadership of Raul Castro. It will proceed far beyond the “Lineamientos” under new generations of Cuban citizens in economic as well as political spheres.

Bibliography

Naciones Unidas, CEPAL, La Economia Cubana: Reformas estructurales y desempeňo en los noventa, Santiago, Chile, 2000, Second Edition.

Oficina Nacional de Estadisticas (ONE), Anuario Estadistico de Cuba (AEC), various years. Website: http://www.one.cu/

Partido Comunista de Cuba, Lineamientos de la Política Económica y Social del Partido y la Revolución, Aprobado el 18 de abril de 2011, VI Congreso del PCC

United nations, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, Preliminary Overview of the Economies of Latin America and the Caribbean, 2010, Santiago, Chile January, 2011

Vidal Alejandro, Pavel, “Politica Monetaria y Doble Moneda”, in Omar Everleny Perez et. al., Miradas a la Economia Cubana, La Habana: Editorial Caminos, 2009

By Arch Ritter

On Friday May 27, 2011, Granma, the official Cuban Newspaper announced a number of additional measures that would reduce the restrictions on micro and small enterprise, notably the “paladars” or small restaurants. (Continuar facilitando el trabajo por cuenta propia http://www.granma.cu/espanol/cuba/27mayo-continua.html)

The objective of the policy changes is to facilitate the expansion of employment in the small enterprise, creating new jobs to absorb workers to be declared redundant in the state sector.

The Government seems to now have the “horse before the cart: rather than the “cart befor the horse” in that job creation is being promoted first, with presumably the lay-offs coming afterwards, or perhaps through a normal process of letting those state sector work centers in personal service areas shut down, if they continuously make losses and have to be subsidized by the state.

There are a number of interesting measures:

1. The most conspicuous measure is to permit the paladares or small restaurants to expand their capacity from 20 to 50 chairs – up from 12 before October.

2. Loss-making state enterprises, notably state restaurants, may be offered for rental to self-employed individuals and operated as “cuenta-propistas”

3. The hiring of up to 5 workers has been extended to all self-employment activities.

4. The “minimum employment requirement” whereby for purposes of paying a tax on each employee a minimum number of employees were required, has been dropped.

5. An exemption on paying the tax on each employee has been granted for the rest of 2011.

6. Some additional new activities have been designated for self-employment;

7. The payment of monthly taxes has been waived for taxi and bed and breakfast operators for up to three months while they repair their vehicles or rental facilities.

8. The monthly up-front payment for bed-and breakfast operators has been reduced for the rest of 2011 from 200 to 150 pesos or convertible pesos (depending on whether they rented to Cubans in Moneda Nacional or foreigners in Convertible Pesos.

A Great New Paladar, with a Lucky Location on the Callejon del Chorro, Plaza de la Catedral

These changes are all reasonable. The government states that it is “learning from experience” (“rectificar en el camino”.) Pragmatism seems to be the growing vogue in economic management and that can only be positive.

Anothe Great Paladar, 23 y Calle G (Avenida de los Presidentes)

Anothe Great Paladar, 23 y Calle G (Avenida de los Presidentes)

The Bildner Center at City University of New York Graduate Center organized a conference entitled “Cuba Futures: Past and Present” from March 31 to April 2. The very rich and interdisciplinary program can be found here: Cuba Futures Conference, Program.

I had the honor of making a presentation in the Opening Plenary Panel. The Power Point presentation is available at “Cuba’s Economic Reform Process under President Raul Castro.”

Oscar Chepe’s recent work on Cuba’s economic situation and the reform process has just been published and is available on the web site: Reconciliación Cubana, or here: Oscar Chepe, Cambios Cuba: Pocos, Limitados y Tardíos

Oscar continues to be a courageous and outspoken analyst of Cuba’s economic policies. In this past, this earned for him a period of forced labor in the 1960s and incarceration in March 2003 along with 75 others. Despite this, he continues to express his views openly and honestly. Although his voice is heard easily outside his own country, within Cuba, his views unfortunately are blocked rather effectively by state control of the publications media, the electronic media and by the continuous violation of the right to freedom of assembly.

Below is a Table of Contents followed by an Executive Summary by Rolando Castaneda.

Table of Contents:

Prologo por Carmelo Mesa Lago 1

Resume Ejecutivo por Rolando Castañeda 6

I. Introducción 11

II. Pequeñas y medianas empresas 14

III. Actualización del modelo económico cubano 16

IV. Problemas de orden externo e interno 19

V. La empresa estatal socialista 22

VI. Mercados mayoristas, precios 24

VII. Cooperativas 27

VIII. Política fiscal 29

IX. Políticas macroeconómicas 31

X. Política monetaria 34

XI. Política económica externa 37

XII. Inversión extranjera 40

XIII. Política inversionista 43

XIV. Ciencia, tecnología e innovación 45

XV. Política social 47

XVI. Salud 51

XVII. Deporte 54

XVIII. Cultura 56

XIX. Seguridad social 59

XX. Empleo y salarios 61

XXI. Política agroindustrial 64

XXII. Política industrial y energética 68

XXIII. Política energética 71

XXIV. Turismo 74

XXV. Política de transporte 77

XXVI. Construcciones, las viviendas y los recursos hidráulicos 79

XXVII. Comercio 82

XXVIII. Conclusiones 84

A 20 años de Primer Informe de Desarrollo Humano de ONU 87

Cuba Bordeando el Precipicio 90

La Economía Cubana en 2010 93

Cuba: Un Principio Espeluznante 100

Oscar Chepe and Miriam Leiva, February 2010. Photo by Arch Ritter

Oscar Chepe and Miriam Leiva, February 2010. Photo by Arch Ritter

Planteamiento general

Los instrumentos aprobados por el gobierno para la implementación del trabajo por cuenta propia, el proceso de la reducción de las plantillas infladas, el recorte de los gastos sociales y el Proyecto de Lineamientos de la Política Económica y Social, revelan pocos, parciales e insuficientes cambios, que no solucionarán la crisis socioeconómica existente.

El gobierno sólo actualiza (“le pone parches”) a las fuentes principales de los problemas actuales: el sistema socioeconómico, que no ha funcionado, es irreparable y está mal gestionado, así como el régimen político totalitario carente de libertades civiles fundamentales. Ellos han llevado al desastre, la dependencia externa e impiden la sustentabilidad económica.

La baja eficiencia, la descapitalización de la base productiva y de la infraestructura, el envejecimiento y estancamiento en el crecimiento poblacional, entre otros muchos males, son consecuencias de ese modelo.

El gobierno elude medidas indispensables mientras propone unas pocas medidas insuficientes, llenas de limitaciones y prohibiciones. También reitera sin corregir apropiadamente medidas anteriores que han sido implementadas con muchas limitaciones y sin tener una concepción integral de la economía, tales como: la entrega de tierras en usufructo, el pago por resultado a los trabajadores y los recortes fiscales.

Los Lineamientos definen que primará la planificación y no el mercado, o sea continuará la burocratización de la sociedad, bajo rígidas normas centralizadoras, que imposibilitan la flexibilidad requerida por la actividad económica y la vida en general de la nación. No se reconoce la propiedad privada y se subraya la política de no permitir el crecimiento de la actividad individual.

La seria contradicción de una política con ribetes neoliberales de drásticos recortes, sin que se brinde a los ciudadanos posibilidades reales de ganarse el sustento decentemente, e incluso aportar de forma racional a los gastos del Estado, podría determinar convulsiones sociales, en un ambiente ya permeado por la desilusión y la falta de esperanza.

El despido de trabajadores y el trabajo por cuenta propia

El vital proceso de racionalización laboral, con el despido hasta abril de 2011 de 500.000 trabajadores considerados innecesarios, el 10% de la fuerza de trabajo ocupada, para continuar haciéndolo posteriormente con otros 800.000, que fue postergado por tantos años, ahora se pretende realizar de forma muy rápida. No se ha contado con la preparación apropiada ni la organización para que tenga éxito en un plazo tan breve y se pueda reubicar una cantidad tan grande de despedidos. Ni siquiera se han modificado los artículos de la Constitución Política (i.e. el 21 y el 45) que se contraponen a lo propuesto.

Al desestimulo por los bajos salarios, la carencia de información técnica, el vacío de reconocimiento social y las generalizadas malas condiciones laborables, a las nuevas generaciones de estudiantes se une ahora la incertidumbre de hallar empleo futuro por el despido masivo de trabajadores.

El trabajo por cuenta propia en sólo 178 actividades permitidas que deberá absorber el despedido masivo de trabajadores, enfrenta graves limitaciones, más severas que las existentes para las empresas estatales y las mixtas con capital extranjero. Incluyen los impuestos por seguridad social del 25% que el trabajador por cuenta propia deberá contribuir, así como los trabajadores que se contraten con base en un salario fijado por el gobierno, a un nivel 50% mayor que el salario medio prevaleciente. También están los elevados impuestos sobre los ingresos personales que pueden llegar hasta el 50% cuando excedan de $50,000 anuales, y las restricciones a los gastos de operación que se permiten deducir de los ingresos brutos para fines tributarios, en algunos oficios de sólo hasta el 10% de los ingresos anuales.

A ello hay que añadir algunas prohibiciones arbitrarias, tal como las sobre el número de sillas de los restaurantes (20) y las barberías (3), así como la ausencia de un mercado mayorista de abastecimiento de insumos. Hasta tanto ese mercado no aparezca, continuará desarrollándose la ilegalidad y, sobre todo, el robo de los recursos estatales, estimulado por el extendido descontrol existente y el miserable salario de los trabajadores. ‘

De esta forma el Estado reduce la actividad individual a iniciativas arbolitos bonsái e impide el crecimiento del trabajo por cuenta propia y el surgimiento de pequeñas y medianas empresa. Un mecanismo configurado para mantener el estrecho control del Estado-Partido sobre la sociedad, temeroso de que el fortalecimiento y desarrollo de la actividad privada pueda convertirse posteriormente en un peligro.

Aspectos generales y macroeconómicos

La mayoría de los Lineamientos sobre aspectos generales, macroeconómicos y sectoriales son enunciativos, generalidades que soslayan la grave situación con la continuada acumulación de graves problemas y sin proponer soluciones reales para los mismos. Desafortunadamente, los cambios requeridos no se avizoran. Este conjunto de 28 artículos se refiere a estos temas y por qué considera que su tratamiento es insuficiente para una sociedad estatizada, llena de distorsiones y carente de racionalidad económica

El problema de la descapitalización física es sumamente serio. Desde inicios de los años 1990 se mantienen tasas de formación bruta de capital fijo en relación con el PIB usualmente inferiores al 10%, menores a las tasas de amortización de los medios de producción y la infraestructura, aceleradas por la falta de reposición, actualización tecnológica y mantenimiento adecuado.

Desprovisto el país de la “ayuda” a inicios de 1990, empezó el deterioro paulatino de la salud pública, la educación, la seguridad social, el deporte y la cultura, con una incidencia muy negativa en los salarios, que como indicara el presidente Raúl Castro el 26 de julio de 2007 son insuficientes para vivir. La permanencia de los esquemas sociales con oportunidades de acceso para todos está en peligro debido a la falta de sustentación económica.

Resulta indispensable introducir tasas de cambio reales. Las tasas actuales, recargadas por gravámenes absurdos, que pueden conducir a análisis distorsionados y por consecuencia a decisiones equivocadas. En especial respecto a la política de inversiones, el comercio exterior y otros aspectos vitales para el desarrollo nacional. Una moneda sobredimensionada representa un serio obstáculo para el crecimiento de la llegada de turistas, al reducir arbitrariamente la competitividad del mercado cubano.

Cuba paga intereses bancarios muy altos a los prestamistas extranjeros; sin embargo, a los nacionales se les abonan intereses sumamente bajos, incluso por debajo de las tasas de inflación reales. Es necesario motivar a la población a depositar sus ahorros en los bancos, en especial aquellos en moneda convertible, dándosele las debidas garantías y el pago de intereses estimulantes y acordes con la situación financiera del país.

El gobierno no contempla la participación de la comunidad cubana en el exterior en la reconstrucción nacional. Un sector de nuestro pueblo que, con el otorgamiento de las garantías necesarias, podría ser fuente de importantes recursos financieros, tecnologías avanzadas, conocimiento y experiencia en la gestión de negocios y posibles nuevos mercados. Habría que adoptar una política pragmática e inteligente de acercamiento a nuestros hermanos en el extranjero, muy en especial hacia la comunidad afincada en EEUU, que además podría ser un puente para mejorar las relaciones con ese país, con enormes beneficios para nuestra economía.

Aspectos sectoriales

En los aspectos sectoriales de los Lineamientos se habla mucho acerca de ejecutar proyectos e inversiones, de potenciar capacidades de diseño y proyección, y fortalecer determinadas capacidades, pero no se define como hacerlo ni como financiarlo.

La esencia de los problemas nacionales, pueden hallarse en la destrucción de la agricultura que ha provocado una extraordinaria dependencia de alimentos importados, incluido azúcar, café y otros muchos que antes Cuba exportaba, mientras, los Lineamientos, reconocen que “ …las tierras todavía ociosas,.. constituyen el 50%…”. El sector está afectado por los precios fijados por el Estado unilateralmente por debajo del mercado, con frecuentes largas demoras en los pagos y las tradicionales deficiencias en la gestión de las empresas acopiadoras oficiales. Las tiendas abiertas para la venta de herramientas e insumos tampoco constituyen una solución, los precios son demasiado altos.

Las Cooperativas de Crédito y Servicios (CCS), donde los productores con muchas dificultades mantienen sus tierras individualmente, con sólo el 18% de la superficie agrícola total (cierre de 2007) han generado tradicionalmente más del 60% de la producción agrícola nacional, así como el más bajo por ciento de tierras ociosas, a pesar de la crónica falta de recursos, el permanente hostigamiento, las prohibiciones y la obligatoriedad de entregar las cosechas total o parcialmente al Estado en las condiciones y a los precios arbitrarios fijados por él.

En este escenario si se continúa con la mentalidad de ejercer estrictos controles sobre los posibles cooperativistas y negando la voluntariedad como concepto básico para la formación de las cooperativas, por muchos “buenos deseos” e indefinidos planteamientos que existan, el movimiento cooperativo no avanzará.

En la industria se refleja con mayor fuerza el proceso de descapitalización generalizado desde principios de la década de 1990. Por ello se requiere con urgencia su modernización y reequipamiento para poder detener la tendencia al actual atraso tecnológico, e incluso la paralización del sector. En 2009 se alcanzó una producción correspondiente al 45% de 1989, incluida la industria azucarera. Si se excluyera esta industria, el indicador sería del 51%. La producción nacional de materiales de construcción es muy baja, con un índice de volumen físico, al cierre de 2009, solo del 27% del nivel de 1989.

El gobierno cubano no publica los ingresos netos por concepto de turismo, por lo cual es difícil evaluar con precisión sus beneficios. Debido al pobre desarrollo de la economía cubana, se importa muchos productos consumidos por los visitantes. Esta actividad podría ser una de las locomotoras que impulse las demás ramas de la economía, pero para ello habría que realizar reformas estructurales, que reduzcan radicalmente la dependencia del exterior.

Conclusión

El aniquilamiento de los sueños de un futuro más justo y próspero para Cuba, podría detenerse si se propiciara un proceso de reconstrucción radical, con el abandono de los dogmas que tanto daño han hecho. Cuba posee significativas reservas productivas inexplotadas y un pueblo que debidamente estimulado, con libertad para crear, podría sacar a la nación de la crisis. Para ello resulta indispensable un nuevo modelo económico, político y social en el cual participarían en paridad de derechos y deberes las iniciativas públicas y privadas, estableciéndose un círculo virtuoso propiciador de desarrollo, que en la medida en que progresen ambas iniciativas se beneficie el país con mayores niveles de eficiencia, así como más y mejores productos, y el incremento del pago de impuestos que haga sostenible la financiación de la educación, salud pública, seguridad y asistencia social, y otros.

By Arch Ritter

The essay attached and summarized briefly here was presented at a conference at CIAPA, in San Jose, Costa Rica, February 3 and 4, 2009 organized by Paolo Spadonu of Tulane University.

The full essay is entitled An Overview Evaluation of Economic Policy in Cuba, circa 2010, June 30, 2010 and can be seen “HERE”. The Introduction and Conclusion are presented below.

Hopefully, this evaluation will change considerably for the better after the Sixth Congress of the Communist party of Cuba in April.

I. Introduction

The economic development of Cuba has been characterized by high levels of investment in people with successful results, but with weak performance in terms of the production of goods and services generally. Cuba’s achievements regarding human development are well known and are epitomized by the United Nations Development Program’s “Human Development Index” (HDI). On the one hand, this index ranks Cuba at #1 in the world for the Education component (somewhat surprisingly) and #31for the Life Expectancy component. On the other hand, Cuba’s world ranking is for GDP per capita in purchasing power parity terms is #94 with an overall world HDI ranking of #51(UNDP, HDR, 2009, 271.) These rankings underline the inconsistency between the Cuba’s high level of human development on the one hand and its economic underperformance on the other. The strong economic performance of the 2004 to 2008 period appeared to constitute a rapid recovery in terms of Cuban GDP statistics. However, this recovery, while perhaps not illusory, was fragile and unsustainable, based on factors such as support from Venezuela and high nickel export prices, and indeed it has been reversed in 2009-2010.

Given the quality of Cuba’s human resources, the economic performance for the last 15 years should have been excellent. The central argument of this essay is that Cuba’s weak economic performance has been the result of counter-productive public policy. The objective of this essay is to analyze and evaluate a number of central policy areas that shape Cuba’s economic performance, including monetary and exchange rate policy, policy towards micro-enterprise; agricultural policy, labor policy, foreign investment policy, policies towards infrastructure renewal, and the policy approach to self-correction and self-renewal.

In order to present a brief overview of the evaluations, an academic style of grading is employed, with an “A+” being excellent through to an “F” representing “failure”.

This evaluation schema is of course subjective, impressionistic and suggestive rather than rigorous. It is based on brief analyses of the various policy areas. However, the schema is similar to the scoring systems widely used in academia, and is used here with no more apology than is normally the case in the academic world.

Before proceeding with the policy analysis and evaluation, a brief overview of economic performance in the decade of the 2000s is presented to provide the context for the examinations of economic policy.

II. General Economic Performance

III. Evaluation of Some Central Policy Areas

IV. Summary and Conclusion:

A summary of the evaluations of the various assessment areas yields an overall evaluation of “D +”. This is not a strong assessment of Cuban economic policies.

The result of such weak policies in these areas is weak economic performance. Badly conceived economic policies nullify the potential efforts of the Cuban citizenry. The major investments in human capital, while fine in their own right, are not yielding strong economic performance. Indeed, misguided policies are undermining, sabotaging and wasting the economic energies and initiatives of Cuba’s citizens.

Major policy reforms amounting to a strategic reorientation of Cuban economic management are likely necessary to achieve a sustained economic recovery and future economic trajectory. So far, writing in June 2010, the Government of Raul Castro has made some modest moves, principally in agriculture, as mentioned earlier. Other policy areas such as those relating to micro-enterprise are reported to be under discussion at high levels in the government. On the other hand, the replacement of the reputed pragmatists Carlos Lage, (Secretary of the Council of Ministers) and Jose Luis Rodriguez, (Vice President of the Council of Ministers and Minister of Economy and Planning) and the replacement of Lage by Major General José Amado Ricardo Guerra of the Armed Forces seems to suggest that the Raul Castro Government may be moving towards a less reformist approach to economic management ( Granma International, 2009.)

The types of policy reforms that would be necessary to strengthen the policy areas discussed above would include the following:

In sum, effective economic management requires new ideas, transparency and criticism, and, indeed, a major policy reform process in order to reverse the current wastage of human energies, talents and resources. Policy reorientations in the directions noted above are unlikely to be forthcoming from the Government of Raul Castro, which appears to be deeply conservative as well as “gerontocratic”. Cuba will likely have to wait for a “New Team” or more likely a “generational change” in its overall economic management before such major reforms can be implemented.

By Arch Ritter

The Economist noted recently that the number of US tourists to Cuba in 2010 reached about 400,000 (January 20, 2011). Surprisingly, the Cuban Oficina Nacional de Estadisticas did not include the United States in its tourism statistics for 2010. (See Oficina Nacional de Estadisticas, Llegada de visitantes internacionales, Diciembre 2010). If the Economist’s number is correct, it represents a huge increase over the 2009 figure of 52,455 tourist arrivals from the United States. The US already appears to be the second source of tourists to Cuba, well ahead of every other country except Canada for 2010.

With the latest easing of travel restrictions for US citizens, one might expect a further large increase in US tourism to Cuba. In 2010, the increase in tourism was likely mainly of a family-reunification character. But in 2011, curiosity tourism will increase dramatically under the new travel rules. Much of this tourism will be in the cities and in Havana in particular – and not in the isolated beach areas where Canadians tend to go. One indeed can expect a surge in tourist services and activities in both the public sector and the reviving private sector. The Paladares. Casas Particulares and other activities should be in expansion mode and should contribute – along with remittances – to a reconstruction boom in Cuba.

By Arch Ritter

As part of the policy reforms designed to absorb almost 1.2 million redundant state sector workers into the private sector, the Government of Cuba has modified the micro-enterprise tax regimen. Some of the modifications were positive in the sense that they will reduce the heavy tax burden on self-employment. However, the changes are modest, and the tax system will continue to limit job-creation and the expansion of micro-enterprise.

The new taxation system, presented in the Gaceta Oficial, número 11, and Gaceta Oficial, número 12 on October 1 and 8, 2010, has five components:

1. Sales Tax on Goods

2. Tax on Hiring of Workers

3. Income Tax

4. Surtax on Services

5. Social Security or Social insurance Payments

Taxes generally will now be payable in Moneda Nacional or “old” pesos. For purposes of tax payment, taxes owing in convertible pesos (CUCs) are to be exchanged into Moneda Nacional at the going quasi-official rate (around 22 to 26 “old” pesos per convertible peso, over the 2001-2010 period). There is a special regimen for bed-and-breakfast operations that is not considered here.

1. Sales Tax

This is a 10% tax levied on the value of sales of goods and payable by all micro-enterprises that do not qualify for the Simplified Tax Regime (See 3. below.) While this tax in principle is reasonable and is used in most countries, the administrative cost of monitoring the value of sales and collecting the tax for the many of the smaller self-employed activities will be high.

2. Tax on the “Utilization of Labor”

This tax on the hiring of employees is set at “25% of 150%” (that is, 37.5%) of the average national wage which was 429 pesos per month in 2009 (ONE, AEC Table 7.4). The tax would thus be about 161pesos per month per employee or 1,932 pesos per year.

A “Minimum” requirement for the hiring of employees for tax determination purposes is set at two employees for paladares and one for other food vendors and a few other activities. There appears to be no exception or adjustment of the tax for part-time employees.

(Note that some 74 self-employment activities are prohibited from hiring employees and another 7 can hire one employee only.)

3. The Income Tax

There are two tax income regimes, a simplified regime for lesser self-employment activities and a more complex regime for larger activities.

The Simplified Tax Regime applies to some 91 activities. In place of the income tax, sales tax, tax on public services, they instead pay a consolidated tax, constituted by the monthly licensing fee which ranges from 40 to 150 pesos per month, payable in the first ten days of each month. (It is unclear whether overpayments would be refunded – they were not under the previous system.)

Other enterprises fall under the general tax regime, and pay all of the individual taxes discussed here. These activities pay the up-front monthly tax/license ranging from 40 to 700 pesos per month.

For the determination of the tax payment, the “tax base” is defined as total revenue less a fixed amount for deductible expenses. The maximum amounts allowed for deductible expenses range from 10% for 10 activities, 20% for room rental operations, 25% for 40 activities, 30% for 10 activities and 40% for 6 food and transport activities. (Bed and breakfast operations have their own specific regimen.)

The income tax rates rise progressively from 0% for the first 5,000 pesos, through 25% for additional income between 5,000 and 10,000, 30% for income increments from 10,000 to 20,000, 30% for 20,000 to 30,000, 40% for 30,000 to 50,000 and 50% for additional income exceeding 50,000.00 pesos. This rate is high but not unreasonable in international comparison.

4. Sales Tax on Services

A 10% additional sales tax is levied on services provided by micro-enterprise. Those enterprises qualifying for the Simplified Tax Regime are exempt from this tax.

5. Social Security Payments

These payments are destined ultimately for old age support, maternity leave, disability and death in the family. They are determined according to a scale that the self-employed worker selects, and may range from 25% of 350 to 2000 pesos per month depending on the choice of the self-employed person. This is a social insurance scheme though the payments are similar to taxes.

This new tax regime represents a minor improvement over the previous regime. The main improvement is that it permits the deduction as costs of production of more than a maximum of 10% of total revenues as was the case previously. This is a reasonable adjustment to the tax base as most of the self-employed activities generate costs that are higher than the maximum allowable 10% of total revenues. This is especially beneficial for activities such as gastronomic, transport and handy-craft or artisan activities for which input costs are far beyond 10% of total revenues.

The progressive structuring of the income tax regime is reasonable though stiff.

However there are a number of flaws in the taxation regimen which will continue to stunt the development of small enterprise and will prevent the absorption of the redundant workers being displaced from the public sector.

1. The Blocking of Job-Creation

First, the tax on employment is problematic as it adds to the employer’s cost of hiring a worker. The obvious impact of this tax will be to limit hiring and job creation. Or employment will be “under the table”, unrecorded, and out of sight of officialdom.

2. Onerous Overall Tax Levels

The overall tax level is punitive. The sum of the income tax, employee hiring tax, and public service surtax is high- and as noted below can help create effective tax rates exceeding 100%, as is explained on Section III. This will continue to promote non-compliance. It will discourage underground enterprises from becoming legal. The establishment of new enterprises will be discouraged.

3. Erroneous and Unrealistic Base for the Income Tax

The most serious shortcoming of the income tax regime involves the tax base which is not “net revenues” after the deduction of input costs, but an arbitrary proportion of total revenues.

The tax regime limits the maximum for input costs deductible from total revenues to 10 to 40% depending on the type of enterprise involved. When the actual micro-enterprise input costs exceed the maximum allowable, the tax rate on true net income can become very high. In the example below, the effective tax rate (defined as the taxes payable as a percentage of true net income) can exceed 100%. Obviously this would kill the enterprise and promote cheating and non-compliance. It will discourage underground economic activities from becoming legal and block the establishment of new enterprises.

4. Continued Discrimination versus Cuban Enterprise in Favor of Foreign Enterprise

The minor reforms of the micro-enterprise tax regime do relatively little to reduce the fiscal discrimination favoring foreign enterprise. (See Table 1.) The main difference is the determination of the effective tax base which is total revenues minus costs of production for foreign firms but for micro-enterprise is gross revenue minus an arbitrary and limited allowable level of input costs. The result of this is that the effective tax rates for foreign enterprises are reasonable but can be unreasonable for Cuban microenterprises. For Cuban micro-enterprises, the effective tax rate could reach and exceed 100%.

Moreover, investment costs are deductible from future income streams for foreign firms this being the normal international convention. But on the other hand, for Cuban micro-enterprise, investment costs are deductible only within the 10 to 40% allowable cost deduction levels.

To illustrate the character of the tax regime, a case of a “Paladar” is examined below. It is assumed that the total revenues or gross earnings of the Paladar are 100,000 pesos per year (Row 1) or a modest 280 CUP or about $US 10.50 per day.

It is imagined then that there are three costs of production cases: Case A, B and C where costs of production are 40%, 60 and 80% of total revenues respectively. A situation where input costs for a Paladar are 80% of total revenues is reasonable, given the required purchases of food, labor, capital expenses, rent, public utilities etc. On the other hand, the 40% maximum is unreasonably low.

The differing true input cost situations (Rows 2 and 3) generate different true net income (Row 6). The tax base however is determined by the legal maximum allowable of 40,000 (Row 4 and 5) and is 60,000 pesos in all three cases (Row 7). The income tax payable is determined by the progressively cascading scale noted above and is 19,750 in all three cases (Row 8, based on calculations not shown here). The tax on hiring the legal minimum two employees is 25% of 150% (that is, 37.5%) of the average national wage which was 429 pesos per month or 161 pesos for 12 months for two employees = 3,864 pesos per year (Row 9). A guess for the surtax on use of public services is 1,200 pesos per year (Row 10). The total taxes then are the sum of Rows 8 t0 10 and are 26,614 per year (Row 11).

The effective tax rate is then calculated as Tax Payment as a percentage of Actual Net Income (Row 11 divided by Row 6). For the third case where true costs of production are 80% of total revenues, the effective tax rate turns out to be well over 100% (124.1%). This is due to fixing the maximum allowable for costs in determining taxable income at an unrealistic 40% while the true costs of production were 80% of total revenues.

The chief result of this example is that effective tax rates can be much higher than the nominal tax rates for all the activities where true input costs exceed the defined maximum. In some cases, taxes owed could easily exceed authentic net income – assuming full tax compliance. This situation likely occurs for all activities not covered by the simplified tax regime.

Such high effective rates of taxation of course could destroy the relevant microenterprise, and block the emergence of new enterprises. While under the previous policy environment for microenterprise, this was perhaps the objective of policy. However, the objective of the new policy environment is to foster and enable micro-enterprise and to create jobs.

Can the Micro-enterprise sector generate about 500,000 new jobs by April 2011 and 1.2 million in the next year? On the positive side, there have been some measures of a non-tax nature (e.g. the stigmatization has been relaxed, licensing has been liberalized; there has been a minor increase in legal activities; prohibitions and regulations have been eased somewhat; and improved access to inputs will likely be possible.) But on the negative side, a narrow definition of legal activities will limit enterprise and job creation; the prohibition of professional activities remains; restrictions and prohibitions on hiring workers remain; and restrictions and prohibitions remain.

The timid revisions of the tax regimen will not facilitate job creation in the microenterprise sector.

In order for the micro-enterprise sector is to expand so as to absorb the 1.2 million redundant public sector workers in the process of being fired, further reform of the tax system is necessary.

The quasi-private restaurants in the Barrio Chino have enjoyed a cultural exemption from the controls placed on normal “paladars” or restaurants. They have faced no 12 chair size limitation. They emerged some time ago as dynamic, large, diverse and efficient restaurants – indeed, the best in Havana. They are a living example of what many sectors of the Cuban economy could become if the tight restrictions and toxic tax levels were all made more reasonable. This is not yet happening. (Photo by Arch Ritter 2008)

.

The quasi-private restaurants in the Barrio Chino have enjoyed a cultural exemption from the controls placed on normal “paladars” or restaurants. They have faced no 12 chair size limitation. They emerged some time ago as dynamic, large, diverse and efficient restaurants – indeed, the best in Havana. They are a living example of what many sectors of the Cuban economy could become if the tight restrictions and toxic tax levels were all made more reasonable. This is not yet happening. (Photo by Arch Ritter 2008)

.

By Arch Ritter

In October 2010, Raul Castro’s Government increased the size limitation on private restaurants from 12 to 20 chairs. This was part of a broader reform package designed to shrink the state sector ultimately by about 1 million workers or 20% of the labour force and to re-absorb them into an expanding small enterprise sector. The 20 chair rule however is symbolic of the positive but timid character of the reforms undertaken so far.

This is an amazing and ironic reversal of fortune for Cuba’s private sector. Small enterprises were almost eliminated in the 1960s, were liberalized from 1993 to 1995 and then were stigmatized and contained by onerous regulations and taxation. Now they are supposed to save the economy, generating jobs, higher productivity and higher living standards than was possible under the old system. 9Raul apparently has even more faith in the small enterprise sector than I do!)

Fidel Castro’s 50-year attempt to construct his own variety of “socialism” is being repudiated and abandoned by his own brother and by the Cuban Government. This is an obvious humiliation for Fidel, even though the genuflections in the media and official documents – including even the “Linamientos” – continue.

Firing one million state sector workers looks risky and brutal. Hoping that they will somehow be absorbed in the small enterprise sector looks like wishful thinking. In other contexts this approach would be labeled “neo-liberal”! Will the laid-off workers have the abilities and aptitudes necessary to start their own businesses?

But the biggest question is whether the small enterprise sector can create 500,000 jobs by March 30 and ultimately one million new jobs. As of November 28, half way through period when the lay-offs are to occur, only 45,000 new self-employment licenses had been issued, with 43% going to retirees rather than those in the labor force. This process is off to a slow start but perhaps it will accelerate.

The regulatory and tax regimes under which small enterprise operated from 1995 to 2010 were designed to contain its growth, to keep enterprises tiny, and to limit the incomes of the self-employed. Now the tax and regulatory framework has been liberalized somewhat:

But tight limits on self-employment remain.

The tax regime has been slightly relaxed but is still problematic. Small enterprises face five taxes: a sales tax (10%), a tax on hiring employees, social security taxes, a public services usage tax, and an income tax (that rises to 50% of income above 50,000 “old” pesos or about $2,000.00 per year.) For the calculation of the income tax, deductible costs of production from total revenues are limited to 10% for simpler enterprises up to 40% for larger enterprises. This means that for a restaurant with actual costs of production of 80% of total income, the tax on actual net revenue exceeds 100%. The tax on hiring an employee is 37.5% of the average monthly wage for Cuba.

For very small-scale activities, an up-front monthly licensing fee that constitutes a simplified tax payment is required.

This revised regime is an improvement over the previous system. It may induce some enterprises to come up from underground and may promote the establishment of some new enterprises. But, on the other hand:

It is therefore unlikely that small enterprise will expand enough to absorb one million redundant workers. By stunting the small enterprises, the possibilities of raising productivity, real incomes and ultimately living standards will also be limited

What happens then? Perhaps the “Fidelistas” could proclaim victory and halt or reverse the reform process. This is unlikely because the old “Fidel” model is discredited by events and by Raul himself. Moreover, Raul’s appointees now dominate the Council of Ministers. His military colleagues hold many key posts in the economy.

More likely, Raul’s Government will conclude that job creation should precede the lay-offs, not vice versa and that their expectations regarding job creation in the small-enterprise sector were overly optimistic. They might then slow down the lay-offs and in time liberalize the tax and regulatory framework.

Raul Castro is finally emerging from 60 years in his elder brother’s shadow. Perhaps he is thinking of his own historical legacy. “History” will never “absolve” Fidel, but it might absolve Raul if he sets Cuba on a course towards a workable economic system – not to mention human rights and meaningful pluralistic democracy.

Since its liberalization in 1993, the production of arts and crafts, largely for the tourist market, has expanded immensely and the quality and diversity of the products has improved greatly. It is now a major source of foreign exchange for Cuba, though statistics on this do not seem to exist. This sector provides another living example of the improvements that could be made in the small enterprise sector generally if it was liberalized appropriately. Above, a photo of the crafts market near the Cathedral on Avenida del Puerto, by Arch Ritter, 2008.

Since its liberalization in 1993, the production of arts and crafts, largely for the tourist market, has expanded immensely and the quality and diversity of the products has improved greatly. It is now a major source of foreign exchange for Cuba, though statistics on this do not seem to exist. This sector provides another living example of the improvements that could be made in the small enterprise sector generally if it was liberalized appropriately. Above, a photo of the crafts market near the Cathedral on Avenida del Puerto, by Arch Ritter, 2008.