By Justin Rohrlich. from “VICE”, , 23 January 2014

Original essay Here: http://www.vice.com/read/millions-of-cubans-may-lose-their-life-savings-this-year

“F___ing cops in Cuba are always busting everybody’s balls.” A man mutters this to me in perfect English as I walk down the once-elegant Calle 23 in downtown Havana. He is the very last customer waiting in a Kafkaesque line that wraps around the block and doubles back on itself twice. The afternoon is stiflingly hot. Two police officers are hassling a nearby teenager because he took off his T-shirt.

“But that’s why things here are so safe,” the man continues, much louder this time. I’m confused until I realize another cop is standing behind me. He wandered over after spotting a Cuban nacional talking to me—an American gusano. “Very safe, very safe. You know, because the police do such a good job!” The officer gives him a long, hard stare, then wanders away. I take my place at the end of the line next to my new buddy, who says his name is Yaniel.

Along with several hundred other Cubans, Yaniel and I are waiting to get into Coppelia, the iconic ice cream parlor created in 1966 by order of Fidel Castro and named for his then-secretary’s favorite ballet. Located across the street from the Habana Libre hotel, a one-time Hilton from which Fidel directed the revolution for three months in 1959, Coppelia has been called the “ultimate democratic ice cream emporium.” But, as I quickly find out, that isn’t exactly true.

When the Cubans around me spot a foreign tourist standing with them in the endless queue, they’re quick to inform me that the line we’re in is for people using Cuban Pesos—which is to say, most Cubans. As a woman in curlers and a tube top explains, people holding Convertible Pesos, the country’s other currency, aren’t forced to endure such Socialist indignities. Foreigners, like me, carry Convertible Pesos. She then points to a tiny building surrounded by a well-kept patio and leafy trees offering respite from the blistering mid-summer sun. There is no line at this Coppelia stand and, sitting in the shade are several happy, relaxed-looking people, enjoying their ice cream.

This, in a nutshell, is what having two currencies has done to the already dysfunctional Cuban economy for the past 20 years. The good news is that the government is finally attempting to fix it. The bad news is that millions of Cubans could lose their life savings in the process.

Kooks and Coops

Cuba is the only country on earth that prints two currencies. When the Soviet Union fell in the early 90s, Havana’s subsidies from the USSR were cut off. As a result, Cuba suffered a devastating 35 percent drop in its GDP. The situation on the ground was dire. In Con Nuestros Propios Esfuerzos (With Our Own Efforts), a 300-page volume of everyday survival strategies distributed in the early 90s by the publishing arm of the Revolutionary Armed Forces, Cubans were offered helpful instructions for how to make shampoo out of rum and “sausages” made of nylon stockings stuffed with seasoned grapefruit rind.

Desperate for hard currency, Fidel Castro grudgingly legalized use of the US dollar in 1993. People working in the tourism industry were allowed to earn—and keep—tips given to them in foreign currency. In addition, a resolution by the National Bank of Cuba permitted some Cuban citizens to own foreign currency; the list included government officials, artists and athletes paid overseas, airline and fishing vessel crews, and employees of foreign embassies or organizations.

Castro’s ultimate goal was to get greenbacks into the state’s coffers. In order to capture as many of the now-circulating dollars as possible, the Cuban government promptly opened a network of so-called “dollar stores,” which carried otherwise-impossible-to-find goods available only to people who used American dollars to pay for them. The Cuban government would purchase, say, cans of Pringles and bottles of Gatorade from American manufacturers thanks to a humanitarian loophole in the then-30-year-old US trade embargo. Then the government would sell the Pringles and Gatorade to citizens at a 240 percent markup. The state kept the profit.

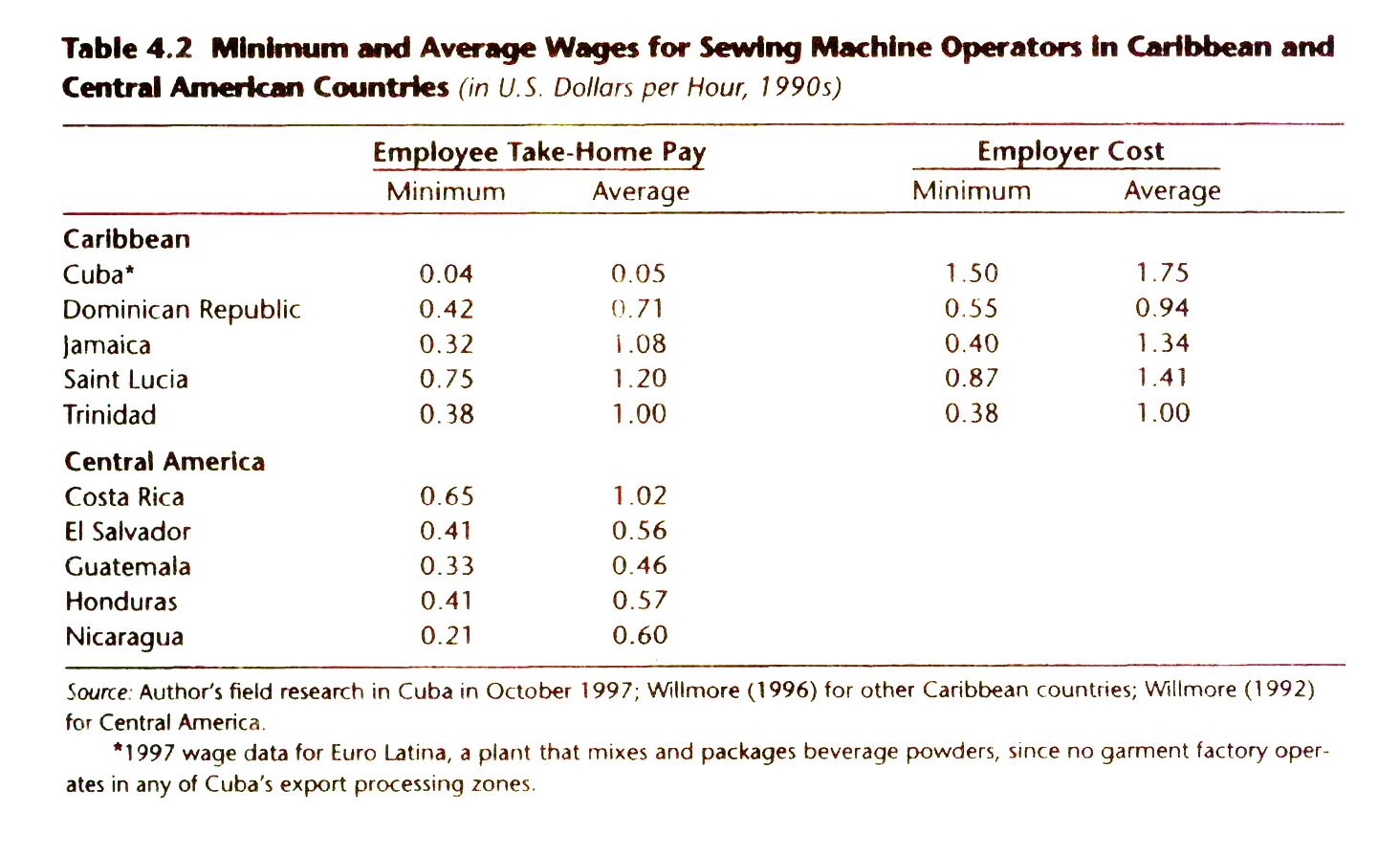

However, the trade embargo made it all but impossible for the Cuban government to do much with their American dollars, especially after the US Federal Reserve fined Swiss bank UBS $100 million for its dealings with the regime. And so, in 2004, Fidel Castro once again outlawed the US dollar and popularized the Convertible Peso, or CUC, which had been in limited use since 1994. CUCs (pronounced “kooks”) are worth one US dollar, and are used primarily in domestic tourism and foreign trade. Cuban Pesos, or CUPs (pronounced “coops”), are worth 1/24th of one CUC—about four US cents—and are what the government uses to pay Cuban salaries. (The government owns just about everything in Cuba, and so nearly every Cuban is a government employee.) Doctors, who are employed by the national health system, earn a little less than 800 CUPs per month. That’s about $30.

Thus, in theory, a cabdriver who gets tipped by foreign tourists in CUCs can earn a cardiologist’s monthly income in a single shift. And since it’s against the law for anyone with a professional degree—doctors, lawyers, accountants, etc—to ply their trade in business for themselves, a domestic brain drain has decimated Cuba’s educated class.

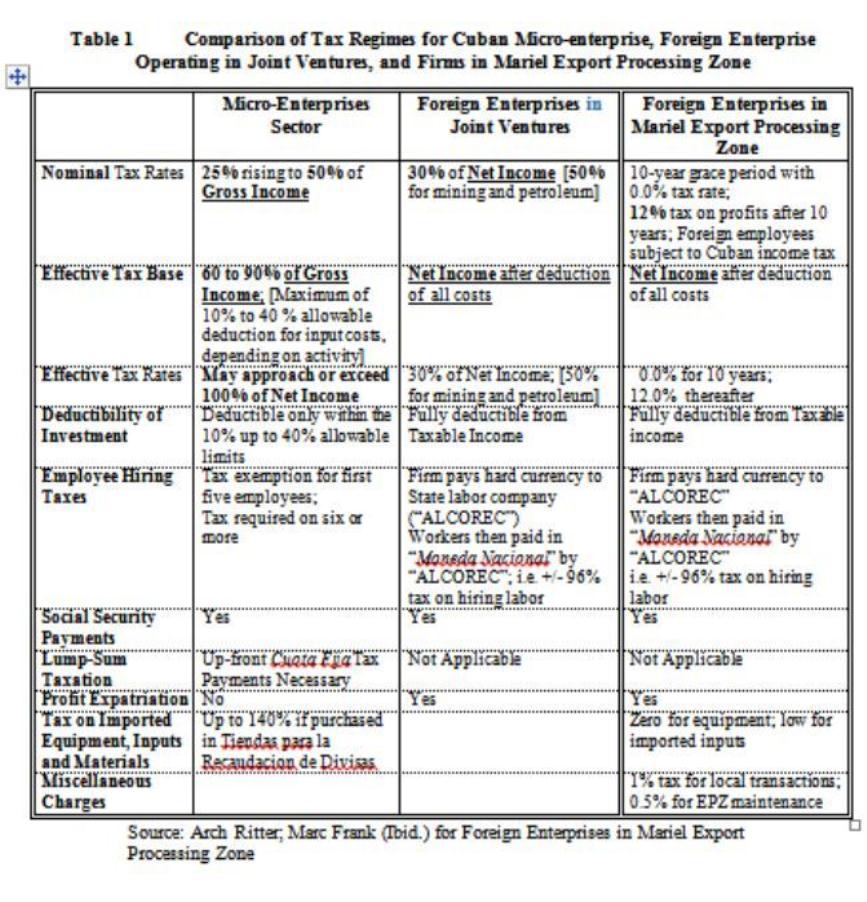

“Basically, the incentive structure that shapes people’s behavior has become completely perverted and dysfunctional,” says economist Arch Ritter, a professor at Ottawa’s Carleton University who has been studying Cuba for almost 50 years.

People with access to CUCs live far more comfortably than those without. Buses that accept CUCs look like the ones you take to pick up your rental car at American airports. Buses that accept CUPs are Soviet-era, exhaust-belching beaters. Essentials like cooking oil and toiletries are easily purchased with CUCs, while CUP earners like Mario, a parking attendant I met one afternoon behind the Habana Libre hotel, ask tourists if they have extras. After I gave Mario a Right Guard Sport Stick and two bars of Irish Spring, he noted that we both have a 36-inch waist. So he asked for my belt.

Cuban President Raúl Castro has quite rightly called the dual currency “one of the major obstacles to the progress of the nation.” However, he has also said, “I was not chosen to be president to restore capitalism to Cuba. I was elected to defend, maintain, and continue to perfect socialism.” So it’s no surprise that the government has announced plans to split the difference and do away with the CUC while retaining its hold on industry and commerce in the country.

How do you eliminate an entire currency? Castro has released few details about how or even when Cuba intends to begin taking CUCs out of circulation. But Ritter explained it this way: “They’ve got to make people want to hold the CUP, through the forces of supply and demand. You increase the CUP’s demand by letting people use it to buy a wider variety of goods. Then, you also limit how many CUPs are available, so its value goes up. Likewise, you reduce demand for the CUC by increasing supply, which would, in time, bring its value lower.”

In Cuba, however, economic decisions aren’t made based on supply and demand, and “the market” as Adam Smith knows it does not exist. Instead, reforms are made with the stroke of a pen, so the government could simply, say, change the exchange rate between the CUC and the CUP from 24-to-1 to 12-to-1. This would instantly halve the life savings of countless Cubans who’ve spent two decades socking away CUCs, to say nothing of the Zimbabwe-like inflation that could strike the economy after such a move.

Or, the government may just take everyone’s savings outright. “My guess is that when the government does the reform, it will expropriate some part of the population’s wealth accumulated in CUCs,” says economist Daron Acemoglu, co-author of Why Nations Fail. “This is exactly the sort of expropriation that Argentina did.”

In the years following the collapse of Argentina’s economy in 2001, the government nationalized private pension funds, swiping roughly $24 billion of the citizenry’s money. Argentinians’ dollar-denominated bank accounts were frozen, and withdrawals were severely limited before everyone was forced to convert their savings into comparatively worthless pesos. The result were protests, a flood of court cases, violent riots, a worsening economic crisis, and a two-week period in which Argentina had five different presidents.

Raúl Castro has declared that the transition will not hurt holders of either CUCs or CUPs. But the concept of protecting individual wealth has no place in Cuba—a fact specifically stated in the Cuban Communist Party’s Lineamientos (Guidelines). And as Mauricio Claver-Carone, executive director of the right-leaning Cuba Democracy Advocates points out, the Cuban government could really use the money.

“The Castro regime seems to undertake these currency operations when it’s suffering from a hard-currency crisis,” he explains. “The anticipated currency swap is simply another episode in a long series of asset confiscations by the Castro regime.”

Expropriations and nationalizations of private property have occurred repeatedly since the beginning of the Castro era. People leaving the island in the early days of post-Revolutionary Cuba were forced to give up their property and assets in addition to their rights as citizens. Those who stayed were soon relieved of 42 percent of their wealth in a top-down currency revaluation. In recent years, the CUC has been devalued in pursuit of stabilizing government debt, and hard currency accounts have been periodically frozen and restricted when it has suited the regime.

The economy of Cuba’s main benefactor, Venezuela, is thought by many economists to be in the midst of collapse. Just as the Soviet Union’s was 20 years ago.

Mucho Resolver

Carlos, like 4.6 million of the 5 million people in Cuba’s labor force, works for the state. A lighting and set designer who lives in the “upscale” Vedado section of Havana, the 74-year-old has accompanied traveling Cuban theater and dance productions all over Latin America and Eastern Europe. The government pays Carlos relatively well for his work; he earns roughly what a doctor earns. Yet even though he is relatively privileged by comparison, Carlos’s monthly salary covers perhaps half a month’s worth of expenses. And so, displaying the optimistic, opportunistic trait known in Cuba as resolver, Carlos makes up for the shortfall by earning CUCs on the side.

Carlos runs a small bed-and-breakfast—known in Cuba as a casa particular—out of his art-deco townhouse. He rents out two rooms—he could rent more, but the government imposes limits on how many rooms can be occupied at once—and charges 30 CUCs a night per room (the authorities also set maximum room rates). On paper, this means Carlos can multiply his monthly salary several times with just a handful of bookings. The reality, however, is another story.

Over the course of the three nights I stay with him, Carlos explains how it works. He pays about 300 CUCs a month to the government for the right to run his casa, whether or not he rents a single room. In other words, Carlos needs to fill one bed for 10 nights a month just to break even with the government, to say nothing of his own expenses. Still, the fact that he’s even still in business means Carlos is ahead of the game. One woman I met selling salsa CDs along Calle 12 in Vedado told me she’d set up her home as a casa particular, but was forced to shut down after just two months because she’d gone broke paying the government fees.

Attracting guests presents a whole other set of challenges. Advertising in Cuba is against the law, and few people are permitted Internet access in their homes, making it all but impossible to attract tourists looking for accommodations. Carlos is among the lucky Cubans who has internet access in the form of an old HP laptop and creaky dial-up connection, allowing him to maintain a web page to market himself to tourists.

First legalized in 1997, casas particulares generate intense competition among Cubans eager for precious CUCs. Mercedes, a rheumatologist who rents me a room in her perfectly preserved colonial mansion in the touristy hamlet of Trinidad, has to contend with dozens of other nearby casas. But in addition to going head to head with each other, small-business owners like Mercedes and Carlos must also compete against Gaviota S.A., a government-run tourism operation overseen by members of Raúl Castro’s inner circle.

A division of the Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces, Gaviota’s tens of thousands of hotel rooms across the island generate the equivalent of almost a billion dollars a year. The money goes directly to the government.

But the big hotels that divert business away from people like Carlos and Mercedes also give other people—housekeepers, bellhops, bartenders—the chance to obtain CUCs for themselves. And state-run entities (particularly ones with bars, restaurants, and plenty of cash on hand) offer opportunities for all manner of graft, theft, and other types of financial chicanery that make up a robust underground economy in Cuba. It’s impossible to put a dollar value on the amount of money that’s stolen or hidden from the state, but economist Arch Ritter estimates that at least 95 percent of Cubans do it.

Isoyen worked at a Soviet-built, Gaviota-run beach hotel on Cuba’s Caribbean coast until he was furloughed earlier this year. When I met him, he told me it wasn’t the loss of his CUP salary that he missed—it was the CUC tips he received from tourists. A college graduate, Isoyen can only use his accounting degree to work for “the people,” making self-employment in his chosen field an impossibility. Living with his parents makes running a casa impossible, so he plans to use his resolver—and the CUCs he socked away—to open an ice cream stand.

For the elderly docents working at Havana’s Museum of the Revolution, resolver means engaging in a bit of basic arbitrage. After showing me Che Guevara’s gun in a glass display case, one of them tries to sell me a three CUP note bearing Che’s likeness as a souvenir. She asks one CUC for the bill. That’s a tidy 88 percent profit.

The Long Con

Resolver can mean a lot of things.

“My friend! My friend!” someone calls out as I walk down Calle E my first morning in Havana. “Where you from, my friend?”

His name is Rafael, and he says he’s a medical student, though he seemingly fails to understand my English only when I ask about the specifics of his education. He’s bald and wiry, and he has a homemade 13 tattoo on the webbing between his right thumb and forefinger. I like him immediately.

Rafael claims to be a licensed tour guide. He even has an official-looking ID card pinned to his shirt. He charges me 20 CUCs—the equivalent of a month’s salary at a typical government job—for a two-hour walking tour in which he listlessly points out a few local sites like the Plaza de la Revolucion and the clinic where soccer legend Diego Maradona supposedly kicked his cocaine addiction in the early 2000s.

We then go to lunch (I pay for it) at a local cafe where Rafael manages to triple his tour fee. For starters, he collects a commission from the restaurant manager for bringing in foreigners with CUCs—and, as I find out later, Rafael’s clients are charged five CUCs for a mojito instead of the usual 24 CUPs, a 500 percent markup. Rafael also sells me a bundle of cigars that he describes as “special, only for Cubans,” for 35 CUC. He’s telling the truth—they aren’t for export. However, I also come to learn they sell to locals for 25 CUP per bundle. (That’s about 1/35th of what I paid.) For his final trick, Rafael gently talks me out of the Everlast speed bag and hand wraps I brought to donate to a local boxing gym, explaining that he would walk them over for me, as the place is “very hard to find.”

As we part ways, Rafael turns to me with an earnest look on his face. “My friend, please don’t tell anybody else this is your first day in Cuba,” he says. “They will take advantage of you.”

Trusting Raul

Cuban citizens hope that Raúl Castro will tackle financial reform as artfully as Cuban citizens tackle financial survival. But the historically awful performance of the Cuban economy under the tutelage of the Castros doesn’t inspire much confidence. Nonetheless, Ernesto Hernández-Catá, former Deputy Director of the International Monetary Fund, has hope.

“This is part of a reform movement orchestrated by a few brave people in the Cuban government,” Hernández-Catá tells me. “It has been accepted by Raúl, who is not a saint, to be sure. But whereas Fidel was a crazy ideologue, Raúl wants to leave behind an image of a guy who is sober, is reasonably intelligent, and wants to improve the lives of his countrymen.”

Whether it turns out to be a failure or a success, the general consensus in the West remains that, while monetary reform is a positive development, Cuba needs to overhaul its entire financial system from top to bottom before real change can take place. While Secretary of State John Kerry called Cuba’s latest slate of reforms a good start—on top of the economic liberalizations, Cubans can now travel outside the country without an exit visa—he said Havana must do more.

And, not surprisingly, Mauricio Claver-Carone of Cuba Democracy Advocates doesn’t see life improving much for Cubans. “The Castro regime will always end up capturing income made in Cuba, one way or another,” he says. “That’s the nature of totalitarianism.”