Capitol Hill Cubans – Oct 24, 2014 – By Maria C. Werlau in Spain’s ABC

Original article: http://www.capitolhillcubans.com/2014/10/must-read-are-cuba-and-brazil-partners.html

The Brazilian government has committed huge taxpayer funds —in loans, subsidies, and direct humanitarian assistance— to support infrastructure projects, food exports, and other initiatives in or for Cuba. Brazil has also provided decisive international political backing to the Cuban military dictatorship. This support is nowhere more evident than in the Port of Mariel, refurbished to great fanfare with Brazilian public financing of over one billion dollars.

Brazil’s massive lending for Cuba seems reckless from a financial/due diligence perspective, as Cuba does not meet basic standards of creditworthiness. The island is technically insolvent; it has US$75 billion in external debt, a long history of defaults, and a classification from The Economist Intelligence Unit as one of the four riskiest countries on the planet to invest in. Meanwhile, the port project is apparently not viable, as the two main reasons given to justify the gigantic investment are shaky at best. Several ports in the vicinity look better positioned to take advantage of the Panama Canal expansion and the U.S. embargo does not seem anywhere close to ending.

Brazil’s huge government loans and subsidies for Cuba have been granted with unprecedented levels of secrecy and are currently under investigation for allegations of corruption, kickbacks, and favoritism towards the port builder, Odebrecht, which received Brazil´s development bank (BNDES) loans for the port construction and is a large campaign contributor of the ruling Partido dos Trabalhadores (P.T.). Moreover, while Brazil has greatly increased financing for projects of politically-compatible foreign governments such as Cuba’s —growing the deficit to 4% of GDP—, public funding for infrastructure projects within Brazil has been lacking.

Brazil’s huge government loans and subsidies for Cuba have been granted with unprecedented levels of secrecy and are currently under investigation for allegations of corruption, kickbacks, and favoritism towards the port builder, Odebrecht, which received Brazil´s development bank (BNDES) loans for the port construction and is a large campaign contributor of the ruling Partido dos Trabalhadores (P.T.). Moreover, while Brazil has greatly increased financing for projects of politically-compatible foreign governments such as Cuba’s —growing the deficit to 4% of GDP—, public funding for infrastructure projects within Brazil has been lacking.

The manifest commitment to support Cuba at all costs may seem puzzling, but can be explained by the strong political-ideological alliance of P.T. leaders with the Cuban regime in the pursuit of a radical hemispheric agenda (inspired in the Foro de Sao Paulo). The hyped-up business opportunities surrounding the port seek to exert pressure against the U.S. embargo and attract investors.

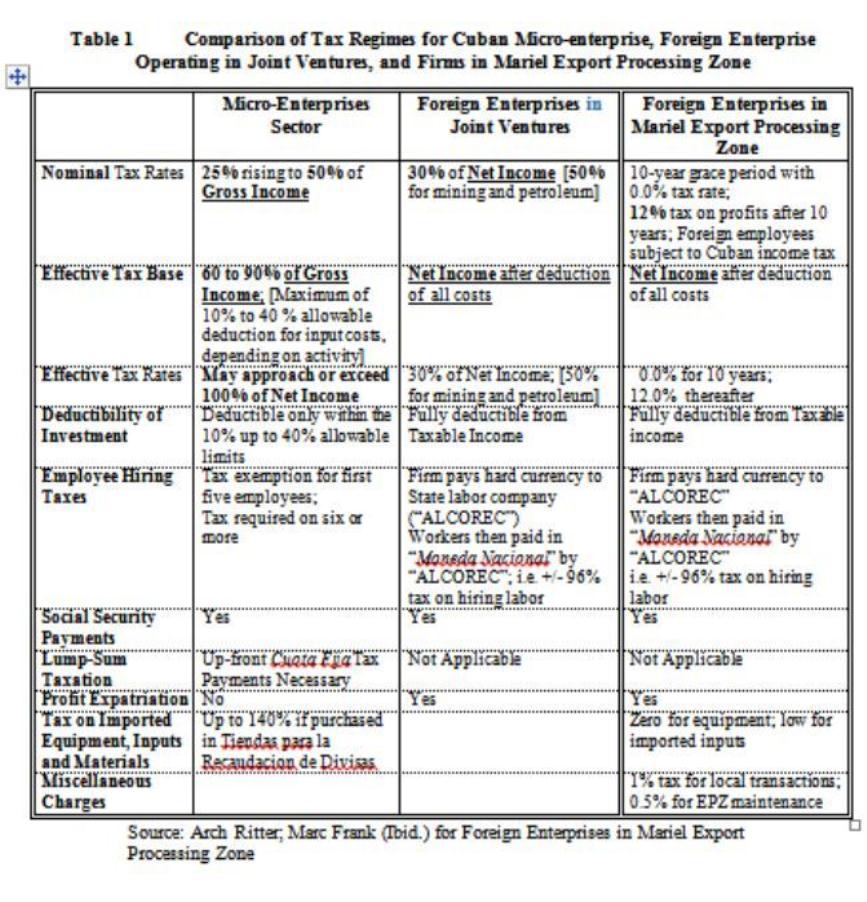

While the Mariel port project does not meet standard repayment conditions, Brazilian officials insist Cuba is meeting its financial commitments, presumably the amortization of its own loans from Odebrecth. In fact, it appears that repayment is coming from exploiting Cuba’s citizens as export raw material for goods and services —purchased mostly by public entities in Brazil— in what arguably constitutes a government-to-government collaboration in human trafficking. Referred to as “health cooperation,” these exports consist of:

- Export services provided by approximately 11,400 Cuban doctors hired out for a Brazilian government program launched in 2013 that generates Cuba estimated annual net revenues of US$404 million.

- Export products reported under standard trade codes for blood — including plasma and medicines and other products derived from blood — and for extracts of glands and organs.

Both have grown exponentially since former Brazilian president Lula da Silva launched the Brazil-Cuba alliance in 2003. Blood imports by Brazil from Cuba were only US$570 thousand in 2002, grew to US$16.9 million in 2011, and totaled US$4.8million in 2013; imports of extracts of glands and organs increased phenomenally from almost nothing in 2003 (US$25,804) to US$88.4 million in 2013.

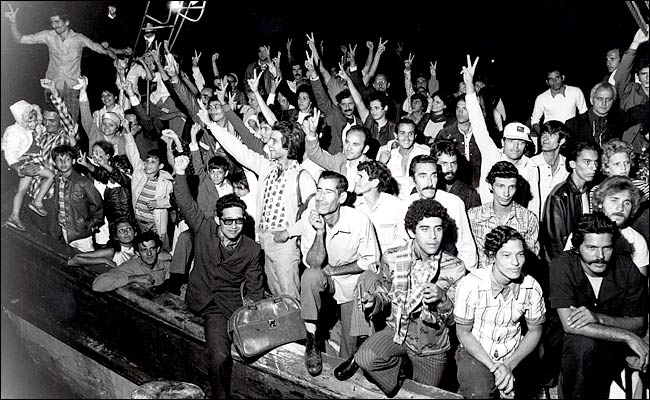

These exports raise serious ethical concerns. The doctors are deployed as “exportable commodities” to remote zones of Brazil in violation of several ILO (International Labor Organization) conventions as well as of international standards and agreements on the prohibition of human trafficking, servitude, and bondage.

Regarding the export products, details are lacking, but if the trade is in products of human origin, as it appears, it would have very troubling implications. In Cuba, blood and organs/tissues/body parts are obtained from voluntary and uncompensated donors unaware of a profit motive by their government and practices involved in their collection —some quite scandalous— are unacceptable by standards of the World Health Organization and other international bodies.

Additional concerns pertain to safety, quality, effectiveness, and the potential political purpose driving the purchases.

While the service of Cuban doctors has raised ample debate and media coverage in Brazil, the import of products purportedly derived from human blood and body parts has, as of yet, remained out of the public sphere.

In addition, while Brazilian authorities move forward with plans to integrate its biopharmaceutical production with Cuba, that this industry is under the absolute control of the secretive Cuban military regime or that it collaborates with rogues states such as Iran and Syria —including with exports of dual-use technology— have yet to raise attention in Brazil. In Cuba, this discussion cannot be had, as all media and mass communications belong to and are run by the state.