Daniele Benzi y Giuseppe Lo Brutto

Daniele Benzi (dbenzi@flacso.edu.ec) Profesor Asociado del Departamento en Estudios Internacionales y Comunicación FLACSO-Ecuador; Giuseppe Lo Brutto (giuseloby@msn.com) Profesor-Investigador del ICSyH, BUAP-México.

En proceso de publicación en Ayala, C., Rivera, J. (2013), De la diversidad a la consonancia: la CSS latinoamericana, AMEXCID/INSTITUTO MORA/BUAP.

El Ensayo completo esta aqui: Benzi_y_Lo_Brutto,Mas_alla_de_la_cooperacion_Sur-Sur

Resumen

Además de constituir el núcleo originario y eje central de la propuesta de integración denominada ALBA-TCP, las relaciones bilaterales entre Cuba y Venezuela destacan en el panorama regional por los estrechos vínculos políticos y económicos establecidos en la última década, que, en la actualidad, se plasman y articulan en un amplio espectro de áreas de cooperación, proyectos conjuntos, inversiones e intercambios comerciales.

Si para algunos autores se trata de un modelo paradigmático y al mismo tiempo novedoso de cooperación Sur-Sur que recupera y se alimenta del legado histórico de solidaridad internacional y entre los pueblos propio de la revolución cubana; otros, en cambio, críticos o escépticos a menudo, prefieren referirse al eje La Habana-Caracas como a un “caso singular” y hasta a una “utopía bilateral” (Romero, C. A. 2010: 127; 2011) inclusive dentro del panorama de las nuevas relaciones y cooperación Sur-Sur.

En el presente artículo, tras caracterizar la posición de ambos países en términos de inserciónregional e internacional, líneas estratégicas en política exterior y áreas de cooperación, los autores abordan el análisis de sus relaciones y vínculos recíprocos, buscando profundizar todos aquellos aspectos útiles para revelar luces y sombras.

Reflexiones finales

Una evaluación de las relaciones entre Cuba y Venezuela resulta una tarea nada sencilla. Al margen de las numerosas informaciones que se desconocen, las cuales indudablemente podrían aclarar distintos aspectos de este peculiar matrimonio en el cuadro de las relaciones internacionales contemporáneas, la valoración final depende en buena medida de la postura política adoptada por el observador. Lo cual implica, además, tener en cuenta factores de orden ideológico, político y de seguridad relativos a ambas naciones y que afectan profundamente sus vínculos, que apenas hemos mencionado a lo largo de este artículo.

Aunque quizás sería oportuno introducir alguna y otra variable de naturaleza política y de clases, en el corto plazo y en términos de coyunturas enfrentadas particularmente críticas, las ventajas en términos globales han sido sustanciales para ambos países. Por ello, desde la perspectiva cubana, Pérez Villanueva (2008: 63) ha afirmado que:

este vínculo abre una serie de potencialidades que podrían aprovecharse para desarrollar programas de reindustrialización, que por un lado complementen y sean funcionales a los sectores más dinámicos de la economía y, por otro, posibiliten la recuperación y el relanzamiento de sectores estratégicos por su impacto en la calidad de vida de la población y sus efectos sobre el sector externo.

Por otro lado, “En cuanto a los servicios médicos que el país exporta, fundamentalmente a Venezuela, su impacto directo en el sector productivo es muy reducido” (Sánchez y Triana, 2008: 82). Sin embargo, agregan los mismos autores:

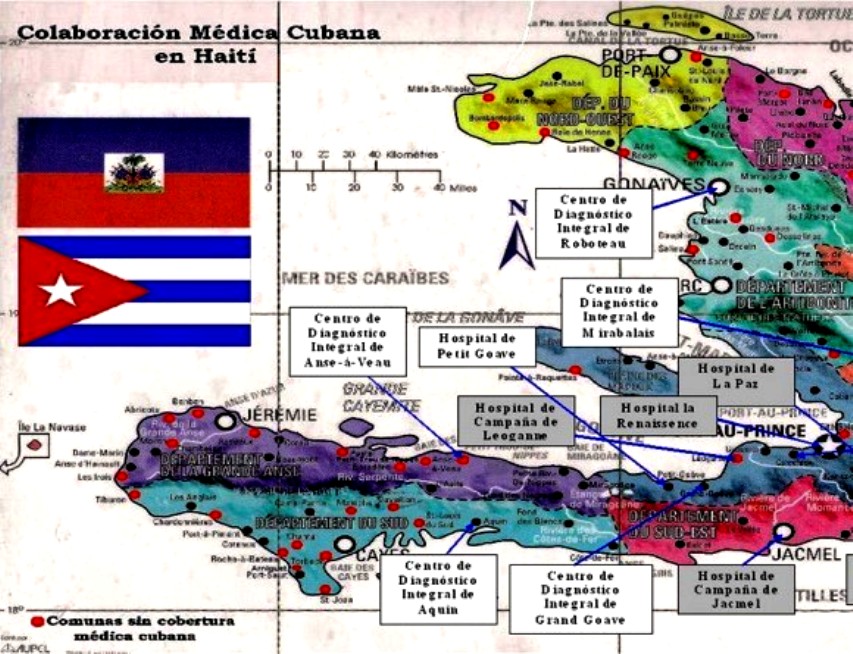

“Otra perspectiva del análisis está en el hecho real de que Cuba ha venido creando una especie de rampa de lanzamiento en torno al sector de la salud. […] Si tenemos en cuenta, junto a los servicios médicos, la exportación de equipos médicos y medicamentos genéricos y biotecnológicos y la inversión en el exterior en el sector biotecnológico junto a negocios de transferencia de tecnología, entonces estamos en presencia de uno de los sectores más dinámicos de la economía nacional, con altas posibilidades de generación de sinergias que potencien su efecto sobre el resto de la economía en un futuro próximo.” (Ibidem: 91)

No obstante, a la vez que algunos cuestionan la supuesta capacidad de los servicios médicos de volverse una efectiva “rampa de lanzamiento”, evaluándolos más bien como una peligrosa “terciarización disfuncional de la estructura económica” (Monreal, 2007, cit. en Mesa-Lago, 2008: 47), la actual dependencia energética y financiera de Venezuela, junto a lo que se percibe como una escasa diversificación de las relaciones económicas y comerciales del país, constituyen de momento el factor crucial de la realidad cubana. Una dependencia que, además, como advierte Mesa-Lago (2011: 5), “creció justo cuando la economía venezolana sufrió el peor desempeño regional”.

Otro punto importante a considerar es el impacto de la exportación de servicios médicos o salida de cooperantes a Venezuela y a otros países en el desempeño del sector nacional de salud. Si por un lado, como aclara Feinsilver (2008: 121), “la diplomacia médica ha proporcionado una válvula de escape para los disgustados profesionales de la salud que, aunque han sacrificado su tiempo, estudiado y trabajado con ahínco, ganan mucho menos que buena parte de los empleados menos calificados de la industria del turismo”; por el otro, el déficit interno es ahora evidente. Mesa-Lago (2011: 17) calcula “que aproximadamente un tercio de los médicos está en el exterior”. Así, sigue el autor, “Uno de los acuerdos [del último Congreso del PCC] estipula garantizar que la graduación de especialistas médicos cubra «las necesidades del país y las que se generen por los compromisos internacionales»” (Ibidem).

Por todo lo anterior, no resulta sorprendente constatar que mientras en Cuba el vínculo con la República Bolivariana es visto por lo general como una oportunidad para la mejora social y el necesario relanzamiento de la economía del país, muchos teman al mismo tiempo el repetirse de la tragedia de un nuevo CAME, tanto más en cuanto particularmente a partir del referéndum de 2007 perdido por el oficialismo en Venezuela y de la crisis económica de 2008, se revelaron cabalmente las fragilidades de un aliado estratégico y vital, como hemos visto, en el sentido literal de la palabra.

Entre 2008 y 2009, en efecto, una serie de eventos fuera del control de los gobiernos cubano y venezolano se ha encargado de evidenciar la inestabilidad y los límites de una alianza cuya principal fortaleza es dada por la afinidad humana e ideológica entre las respectivas cúpulas del poder y, sólo hasta cierto punto, de las elites políticas y algunos segmentos de la sociedad civil y organizaciones populares.

La drástica, aunque temporánea, caída en los precios del petróleo, sumándose en el caso de Cubaal desplome del precio mundial del níquel, de la reducción de los ingresos por turismo, de las remesas y del impacto catastrófico provocado por el paso seguido de tres huracanes, destacaron la impotencia de los subsidios y solidarid bolivariana para mantener a flote una economía estancada, en un cuadro de agotamiento y necesario replanteamiento también de la dinámica política.

Para esta fecha, sin embargo, esas cuestiones ya habían sido asumidas por la dirigencia cubana como un problema, a la hora de darle forma y contenidos al proceso de “actualización” del modelo. En este sentido, el pragmatismo de Raúl Castro y el ajuste intraelite que supuso su definitiva toma del poder, han significado también, en un marco de continuidad por el momento, un cambio cualitativo y de perspectiva en la relación con Venezuela, cuyos contornos apenas empiezan a esclarecerse.

Lo único cierto, por ahora, es que tanto la consolidación de la “utopía bilateral” que tanto preocupa a Carlos A. Romero (2011), como la “ilusión neocastrista”, en palabras de Alain Touraine (2006), de emprender nuevamente un proyecto revolucionario a escala continental a partir del eje La Habana-Caracas, ya no figuran en la agenda de quienes, verosímilmente, llevarán por un tiempo todavía las riendas del proceso de “actualización” del socialismo cubano31 .

Desde la perspectiva venezolana, la evaluación se torna tal vez aun más complicada. Hasta los críticos más enconados y menos reflexivos tienen cierta dificultad a la hora de sustentar con argumentos serios la descalificación total de la cooperación cubana dentro de las Misiones, unque éstas fueran meras políticas de corte asistencial con un perfil netamente partidista y/o políticoideológico.

Briceño (2011: 71), por ejemplo, sostiene que “Es cierto que Venezuela se ha beneficiado de la ayuda cubana en el desarrollo de las Misiones, pero surgen [algunas] cuestiones. La primera es la cuestión del equilibrio en la cooperación, que en el caso concreto del ALBA se plantea en comparar el aporte de la cooperación de Venezuela con Cuba, y la de este país con Venezuela”. El tema de las asimetrías en la cooperación ofrecida y recibida es inocultable y lo sería probablemente aun más en la medida en que fueran oficializadas las cifras estimadas en los párrafos anteriores y, especialmente, las que se refieren al supuesto sobrepago por servicios profesionales médicos.

Nuestro punto, sin embargo, en el marco de estas conclusiones, es otro. El gobierno bolivariano, aunque quizás no parezca evidente, también ha desarrollado cierta dependencia tanto de los servicios médicos cubanos, como en general de la asistencia técnica y política, así como en la orientación ideológica y hasta simbólica procedente de este país.

Si en algunos sectores y programas efectivamente se podría cuestionar un “exceso” de cooperación – en términos de presencias, capacidad operativa, escasa coordinación, oportunidad y/o falta de resultados – la colaboración cubana es por el momento un ingrediente esencial de las políticas desplegadas con las Misiones y de los resultados obtenidos en distintos indicadores.

De instrumento transitorio y excepcional, se ha pasado a su multiplicación y establecimiento semi permanente, pero siempre paralelo a las estructuras preexistentes, manteniendo un carácter híbrido de dispositivo extraordinario en mano del poder ejecutivo, que ha creado “una numerosa y desordenada burocracia paralela al funcionariado ministerial formal existente, para atender el desarrollo de cada actividad propia en estos programas sociales” (Viloria, 2011: 8-9)33 .

En el caso de Barrio Adentro, además, la Misión médica cubana goza de una autonomía cuasi absoluta con respecto a las autoridades venezolanas y al resto del sistema nacional de salud. Si por un lado se podría poner en tela de juicio su capacidad para llevar a cabo un programa tan complejo y prolongado en el tiempo en un país tan polarizado como es actualmente la República Bolivariana, por el otro, a pesar de no ser la única responsable de esta situación, su autonomía y falta de articulación con otras instituciones supone determinados problemas tanto legales como de funcionalidad y efectividad de resultados34. A pesar de la destacada actividad médica cubana a lo largo de los últimos decenios, lo cual ha implicado ciertamente un importante proceso de aprendizaje y reflexión sobre si misma, el hecho de que la colaboración con Venezuela sea de lejos el programa más amplio y complejo jamás emprendido, determina nuevos e insoslayables desafíos que son al mismo tiempo técnicos, éticos y políticos.

Después del giro de 2006-2007, al lado de las Misiones surgidas para experimentar las nuevas políticas e instituciones socialistas, la última generación de estos programas ha abandonado el carácter inicial de complemento a las políticas económicas y de desarrollo, para reproducir, por una parte, políticas meramente compensatorias y focalizadas; y, por la otra, sustituirse a lo que debería ser la acción ordinaria del gobierno y de sus Ministerios.

Lo anterior, evidentemente, está íntimamente atado a la característica estructural de Venezuela en cuanto Estado-nación, esto es, ser un país rentista-petrolero, lo cual produce y reproduce ciertas “creencias en los atajos, las soluciones cortoplacistas, la creencia de un país rico”, con el resultado de que muchas propuestas “en gestión de políticas públicas dirigidas a erradicar a la pobreza, descansen en el asistencialismo y en la transferencia de recursos económicos de forma directa, hacia aquellos sectores poblacionales seleccionados como beneficiarios de los programas sociales” (Viloria, 2011: 8).

Por paradójico que pudiera aparecer, esta condición encuentra un terreno particularmente fértil y potencialmente perverso tanto en el voluntarismo típico de todo proceso revolucionario y muy presente en Cuba a lo largo de su historia, como, por un lado, en una concepción anquilosada del socialismo y del papel del Estado, la cual produce ciertas formas de paternalismo y parasitismo social; y, por el otro, en las urgentes e insoslayables necesidades económicas del régimen cubano y de sus propios cooperantes.

Camilo Cienfuegos Refinery

The Venezuela-Cuba Undersea Cable Arriving in Cuba, 2011