Carmelo Mesa-Lago, University of Pittsburgh,

Latin American Research Review, July 2017 https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.2

This essay reviews the following works:

Open for Business: Building the New Cuban Economy. By Richard E. Feinberg. Washington DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2016. Pp. vii + 264. $22.00 cloth. ISBN: 9780815727675.

Miradas a la economía cubana: Análisis del sector no estatal. Edited by Omar Everleny Pérez Villanueva and Ricardo Torres. La Habana: Editorial Caminos, 2015. Pp. 163. $5, paper. ISBN: 9789593031080.

Entrepreneurial Cuba: The Changing Policy Landscape. By Archibald R. M. Ritter and Ted A. Henken. Boulder, CO: First Forum Press, 2015. Pp. xiv + 374. $79.95 cloth. ISBN: 9781626371637.

Retos para la equidad social en el proceso de actualización del modelo económico cubano. Edited by María del Carmen Zavala et al. La Habana: Editorial Ciencias Sociales, 2015. Pp. vi + 362. $20 paper. ISBN: 9789590616105.

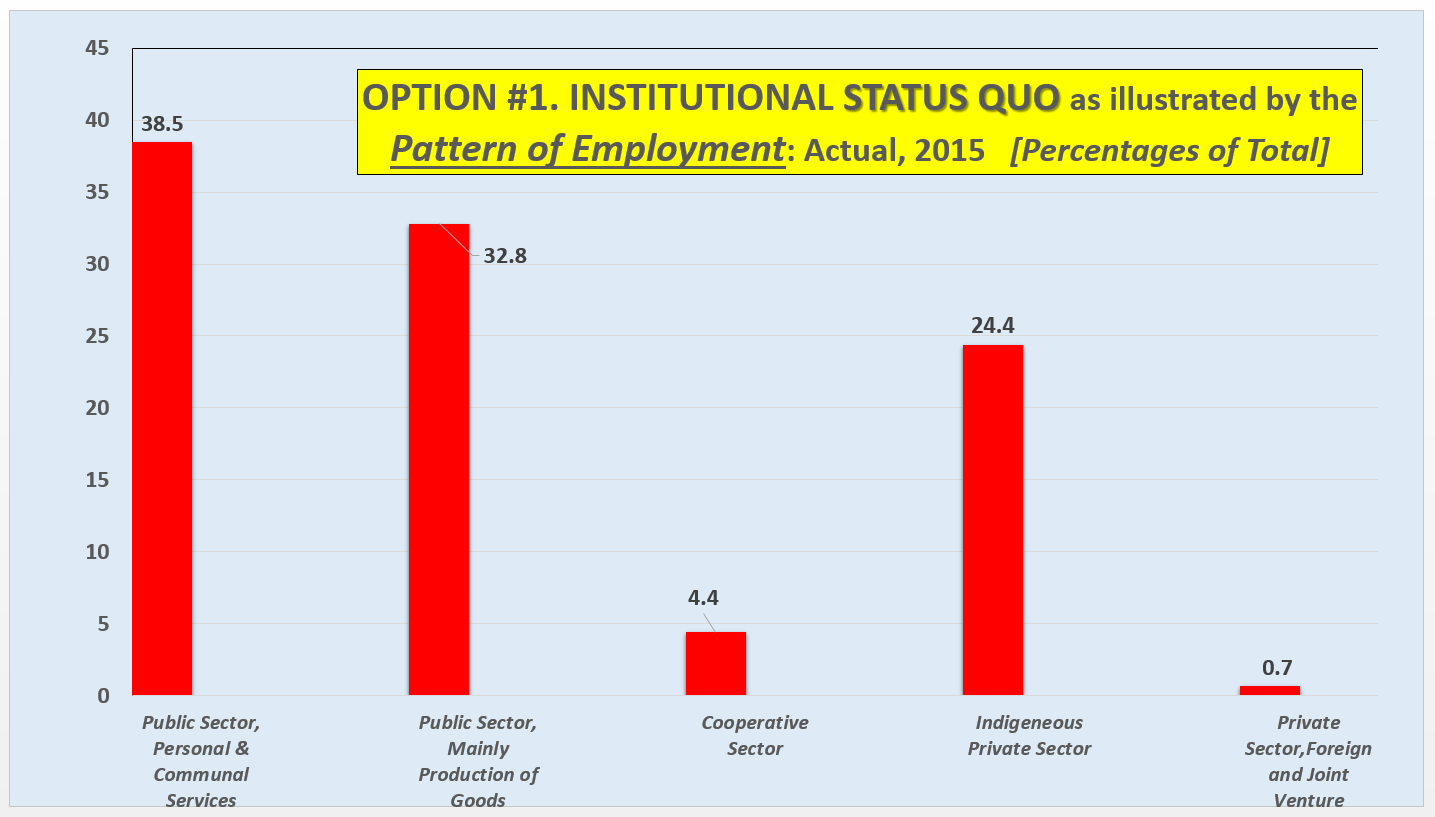

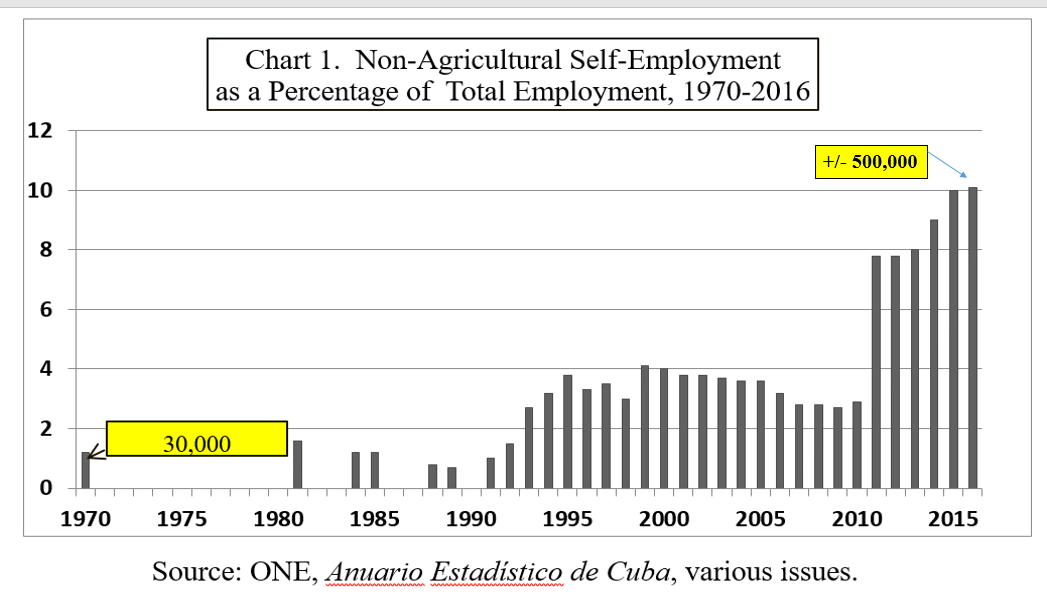

Soon after current president of the State Council Raúl Castro took over power in Cuba from his brother Fidel in 2006, he started structural reforms to cope with the serious socioeconomic problems accumulated in the previous forty-five years. Some authors, including a few in this review, argue that Cuba is in transition to a mixed economy. Despite the importance of these changes, however, the official view is that central planning will predominate over the market, and state property over private property.1 A main reform goal was to fire 1.8 million unneeded workers in the state sector, which demanded an expansion of the “non-state sector” (NSS) to provide jobs to those dismissed. The four books I review are commendable additions to the growing literature on the NSS (inside and outside Cuba), as they fill some of its existing gaps, to be identified below.2 A few authors rely on surveys to gather data, but surveys are not easy to take in Cuba; hence the majority used interviews of different size and representativeness, as well as in-depth conversations.

Within the NSS, the most dynamic four groups are self-employed workers (507,342), usufruct farmers (312,296), and members of new nonagricultural and service co-ops, NASCs (only 7,700 so far). Altogether these make up 17 percent of the labor force, out of a total 29 percent in the entire NSS.3 Except for the most recent NASCs, the other three forms were legalized during the severe crisis of the 1990s but did not take off until much later. Selling and buying of private dwellings, banned in 1960 and reauthorized in 2011, involve at least 200,000 transactions but still only 5 percent of the total housing stock. The books reviewed in this essay mainly concentrate on self-employment and to a much lesser extent on NASCs.

The main gaps treated by the books are the NSS’s history; size and personal profiles; relations with the state; progress achieved and obstacles faced; the role of variables—age, gender (most treated), race, education, and location—on growing inequalities; particular issues such as access to raw materials, capital and credit, competition, and taxes; and NSS perspectives. This review discusses the data, method, and evidence that each researcher uses and the major issues and findings, arguing that the size of the NSS remains questionable.

In Entrepreneurial Cuba, Archibald Ritter and Ted Henken combine their economic and sociological expertise to produce an encyclopedic, balanced, and laudable volume on the development of the NSS in Cuba. Targeted on self-employment and, to a lesser extent, on NASCs, the book also tackles broader topics like the “underground” economy. It starts with an examination of small enterprises in general, internationally, and its lessons for Cuba. Based on historical and comparative approaches, Ritter and Henken discuss the evolution of self-employment throughout Cuban contemporary history. In the socialist period, they compare Cuban policies with those of the USSR and Eastern Europe; furthermore they contrast Fidel’s hostility to the NSS (except for reluctant support in times of economic crisis) with Raúl’s more pragmatic and positive style, which does not exempt the sector from tight controls, restrictions, and taxes. Largely based on my cycles approach,4 the history of self-employment under socialism is divided in three periods (each one covered in a chapter): 1959–1990, trajectories and strategic shifts; 1990–2006, the “Special Period”; and 2006–2014, Raúl’s reforms.

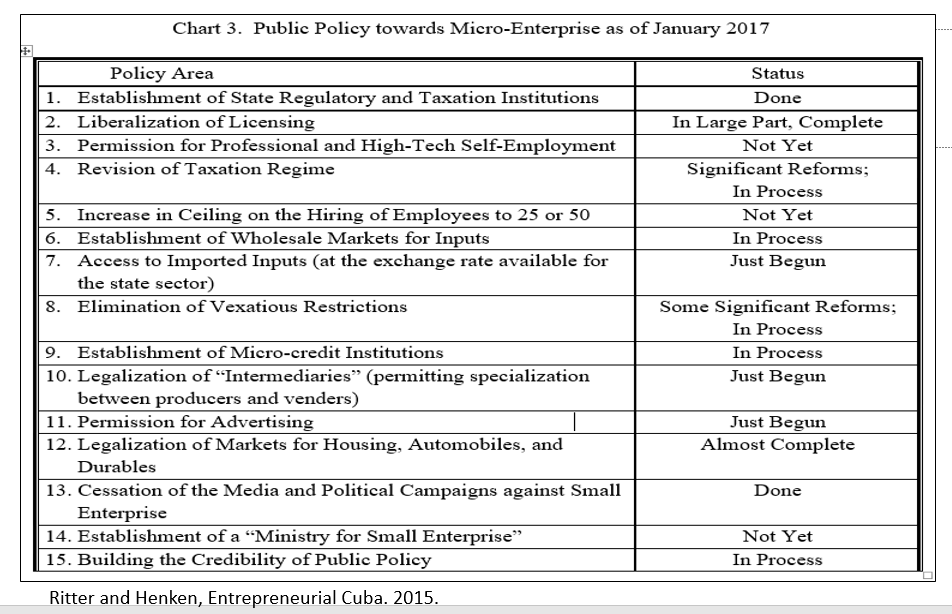

Ritter and Henken conclude that the NSS has grown and achieved substantial progress: for instance, increase in authorized activities and licenses, broadened legal markets, deduction of part of the expenses for tax purposes, micro credits and banking facilities, and rental of state facilities. Conversely they identify limitations, like narrow definition of legal activities, exclusion of most professional and high-tech occupations, multiple taxes and taxation at a high level, lack of wholesale markets, bureaucratic resistance, obstacles to hiring employees, and discrimination in favor of foreign firms. They provide suggestions to overcome these problems. Lack of space impedes a more profound treatment of this book, the most comprehensive and profound on self-employment so far. The structure of the book, combining historical stages and current analysis of self-employment and NASC, however, is somewhat complex and leads to a certain overlapping.

Ritter and Henken rely on three series of interviews conducted in Cuba with sixty self-employed workers in 1999–2001, half of them re-interviewed in follow-up visits in 2002 and 2009 and, finally, some revisited in April 2011 to evaluate the impact of Raúl’s reforms. The authors select the three most dynamic, lucrative, and sizeable private activities: small restaurants (paladares), taxis, and lodging. They asked their informants about three issues: (1) ambitions and expectations for the future (whether they expected to become true small- and medium-sized enterprises—SME—in the long run); (2) survival strategies in negotiating with the state (how they responded to the government regulations, licenses, and taxes); and (3) distinctions between licensed and clandestine self-employed workers.

Accompanying abundant evidence, deep analysis, statistical tables, synoptic charts, figures, and useful appendices (including a list of the 201 authorized activities for the self-employed and a timetable of the evolution of NSS in 1959–2014), the authors intersperse vignettes that allow the reader to better understand the daily life of the self-employed. Occasional jewels in the book brighten our knowledge, such as uncovering in fascinating detail the bureaucratic shutdown of El Cabildo, which was the most prosperous private, medium-sized business in Cuba.

Miradas a la economía cubana, a collection edited by well-known Cuban economists Omar Everleny Pérez Villanueva and Ricardo Torres, includes twelve essays that offer a first-rate sample of scholarship on the NSS at the Center for the Study of the Cuban Economy, the best economic think tank in Cuba. The anthology, an excellent complement to the Ritter and Henken book, includes self-employment and NASCs. In the prologue, Juan Valdés Pérez notes that “the new economic model in Cuba is moving [transita] toward a mixed economy, based on a public sector, a mix-capital sector, and a private sector, mostly SME” (14). Most contributors to the volume propose reasonable policies to help the consolidation and further expansion of the NSS.

In the opening chapter, Torres discusses the role of the private sector in a centrally planned economy such as Cuba, which generates an intrinsic conflict. Despite NSS advances, the government still sees it as a supplement to the state sector and imposes clear limits. Hence the NSS role is and will continue to be very minor, if currents trends hold. An important point, among many discussed by Torres, is that its productivity is low, despite the very highly educated labor force (ranked at the top of Latin America), and shows a declining trend due to the low skills of the activities approved. He ends by suggesting, “In a scenario [Cuba] where public enterprises are predominant and mostly inefficient, wealth is not socialized and man is not liberated from alienation, just the opposite” (25). Torres believes that the solution to all existing problems is neither privatization of all public assets nor to insist on old formulas overcome by time, and urges a serious national social debate on these issues.

Pérez Villanueva analyzes and defines self-employment and SME, tracing their evolution and identifying needs such as autonomy, a wholesale market with competitive prices, facilitation of payments through the national banks, and use of highly skilled personnel; he also notes adverse effects like social inequalities (see Zavala et al., below). At the end of his chapter, he asserts that “the Cuban SME would be more viable than the actualization of our economic model and contribute more positive results, providing that the government understands its role and potential” (35).

Camila Piñeiro provides the most comprehensive and deep analysis of NASCs so far. These cooperatives grew 74 percent, from 198 to 345, in 2013–2014, but their tempo slowed to 6 percent in 2015.5 Based on diagnosis and audits done on sixty NASCs in 2014, Piñeiro identifies their achievements (increase in income and motivation, improvement in the locale and working conditions) and problems (complex and delayed creation, insufficient training, and lack of a wholesale market). The most successful NASCs are those created by the voluntary initiative of a group of persons that share the same goals and values (23 percent of all NASCs), and the least successful are those coming from former state enterprises, without negotiating with their workers so that they accept what is decided from above (77 percent).

Mariuska Sarduy, Saira Pons, and Maday Traba analyze tax evasion and underdeclaration of income among self-employed owners. They report that evasion was 12 percent of total fiscal revenue and 60 percent of registered self-employed contributors in 2013–2014. They carried out 300 interviews with self-employed workers in Havana in 2014 and found that 55 percent omitted income in their declaration for the following reasons: 95 percent due to very high taxes; 77 percent blamed the complex procedure to pay taxes; 80 percent knew that evasion or underdeclaration are toughly penalized crimes, but half believed that they were necessary to survive, and 20 percent thought that it was improbable that fiscal authorities would catch them.

Expanding her substantial work on geographic inequalities, Luisa Íñiguez uses the 2012 population census to explore the distribution of NSS enterprises in Cuban provinces and municipalities and shows their differences and contribution to social inequalities. She develops various maps of the island, displaying the location of total NSS enterprises, as well as key components such as the self-employed, usufruct farmers, and small private farmers. In addition, she calculates percentages of components of the NSS relative to the employed labor force. The NSS developed much further after 2012, but her work remains valuable and sets a solid foundation for future study.

The role of women in microenterprises is examined by Ileana Díaz and Dayma Echevarría, relying on data from the 2012 population census and Ministry of Labor and Social Security in 2013, and a survey of thirty-five self-employed owners in Havana circa 2014 (63 percent women and 37 percent men). Among other gender inequalities, they find that women are more hurt than men by the lack of a state policy to foster microenterprises, and by poor access to credit as well as to legal and accounting advice. Interviewees answered key questions with a fair consensus: 50 percent noted unfair competition from state and mixed enterprises; most preferred to work as self-employed instead of for the state; public or private financing was judged insufficient; elementary-secondary school didn’t help in their activity but university did; and they noted poor access to wholesale markets, telecommunications, and vanguard technology. Virtually all interviewees, but a sizably lower percentage of women than men, said that their success was more than expected. Both genders agreed on the major obstacles: limited demand, excessive state bureaucracy and regulations, too much competition, absence of a wholesale market, and difficulties to get inputs.

Retos para la equidad social, edited by Maria del Carmen Zavala et al., contains twenty contributions, all but one authored by women, focused on socioeconomic inequality under Raúl’s structural reforms. Three chapters of the book deal with expanding inequalities among the self-employed by age, gender, race, education, and location, and also with their motivation, satisfaction, competition, capital access, obstacles faced, and views of the future.

The best chapter in the collection, by Daybel Pañellas, Jorge Torralbas, and Claudia Caballero, relies on a survey taken between October 2013 and March 2014 among 419 persons self-employed in fifty-seven activities and located in three districts of Old Havana. They find that age, gender, education, and location are important factors in the quality of occupation, access to capital, and earnings of the self-employed. In the sample, 76 percent worked by themselves, without employees; 13 percent were employers and 11 percent employees; 64 percent were men and 36 percent women; 48 percent were white and 52 percent nonwhite; 54 percent were middle-aged adults, 30 percent young people, and 15 percent elderly; 54 percent had precollege or university education, 31 percent had a low level of education, and 15 percent had a technical education (a highly trained labor force and NSS, also noted by Torres). Not only are women underrepresented, but their activities reproduced their roles in domestic life, such as work in cafeterias, food preparation, manicure, makeup, and as seamstresses. While women rented rooms mostly in national pesos (CUP), men rented rooms in the more advantageous convertible pesos (CUC = 24 CUP). Combining education, race, and gender, the best-educated white males had better occupations than the lowest trained nonwhite females (e.g., computer programing vis-à-vis seamstress). The self-employed were mainly attracted by these features of self-employment (not exclusive categories): better income (80 percent), easier labor journey (20 percent), and being their own bosses (15 percent). Their level of satisfaction ranged from so-so (53 percent), to good/very good (38 percent), to bad/very bad (9 percent)—the higher the educational level the more occupational satisfaction.6 Success in competition was attributed to the quality of product or service (56 percent), business location (24 percent), and low prices (14 percent). Access to capital was mostly by employers that receive remittances, are white, and have higher or middle education, ample social networks, and good locations; conversely, investment is minimal among low-educated nonwhites. Obstacles encountered by the self-employed were lack of access to raw materials (49 percent), heavy taxes (44 percent), lack of financing (35 percent), state control and inspections (33 percent), and legal procedures (23 percent). These proportions varied in the three districts and were influenced by gender, race, and type of activity; for example, controls and inspections were mostly mentioned by workers with low education, nonwhites, and women. On their perceptions for the future, 81 percent believed that the self-employed would prosper—especially if the mentality of the state and the self-employed changes— and 10 percent didn’t think so.

Geydis Fundora expands on the growing inequalities enumerated above, based on a study of fifty-two self-employed residents of Havana Province in 2010–2013, reaching similar conclusions. Out of the 201 activities approved, 65 percent have a male profile; paladar owners mostly hire women because of their sex appeal to clients and because the work is similar to that done at home; other activities are in practice barred to the “weak sex.” Men tend to be employers and women employees, thus resulting in lower decision making and income for women. The elderly are disadvantaged because most activities require physical strength; most young people are hired as employees and in less specialized activities. There is no political will to gather statistics on race, but whites predominate over blacks and mulattoes, opposite to what Pañellas, Torralbas, and Caballero found; nonwhites have less access to capital and hence to success and higher earnings. Those that have a high initial capital—coming from savings, remittances, or hidden foreign investment—enjoy an advantage over the rest not only to establish the business but also to buy inputs, pay taxes, and bribe inspectors. Location in more attractive and populous zones are keys to success.

Magela Romero targets self-employed women engaged on infant care, a most-needed occupation to increase female participation in the employed labor force, which was 37 percent of the total in 2015;7 the low proportion is an outcome of resilient traditional gender roles at home and work. Based on eighteen cases in the town of Cojímar (in Havana) in 2013, the study found that all those self-employed in infant care were women, and half of them had previously been informal domestic employees. All said that their main attraction was a higher income, but all also complained of exhausting work and high responsibility with a monthly salary of 200 CUP per infant, with a maximum of five infants, equal to US$40, still three times the mean average salary in the state sector.

Open for Business by Richard E. Feinberg deals mainly with the economic events following the process of normalization between the United States and Cuba that started at the end of 2014, preceded by a summary of the previous state of the Cuban economy and Raúl’s reforms. Feinberg believes that the emerging NSS “offers the best hope for a more dynamic and efficient Cuban economy, especially if it is permitted to partner with foreign investment and with more efficient state-owned enterprises” (132). One chapter on emerging entrepreneurs is based on a monograph he published in 2013, which at that time provided substantial data and analysis on self-employment, preceding the other three books reviewed herein.8 One graph and one table are updated to mid-2015, but most of the text remains unchanged. The author and an assistant had in-depth conversations with twenty-five microentrepreneurs between March 2012 and April 2013, emphasizing financial issues (averages of time open, number of employees, starting capital, and use of domestic and foreign capital). Interesting profiles of self-employed activities are given on paladares, cafeterias and catering, bed and breakfasts, accounting, a shop selling handicrafts to tourists, building construction and house remodeling, electronic repairs, and renting of 1950s cars; from such profiles he extracts useful lessons.9 A stimulating innovation is the selection of twelve young Cuban “millennials” (aged 20–35), one of them the owner of a cafeteria, for appealing interviews based on ten questions.

Feinberg envisages four stages of capital accumulation of microbusinesses: primitive household accumulation, early-mover super-profits, growth and diversification, and strategic alliances with state enterprises and with foreign investors (not yet authorized). Like the other authors whose books I review here, he stresses the progress and achievements of self-employment, perhaps more so than other authors. But he also pinpoints the many constraints the self-employed face: poor banking and meager credit, serious scarcity of inputs of all sorts (as a visible exception he gives the wholesale market “El Trigal,” temporarily closed in May 2016), shortage of commercial rental space, a very challenging business climate, and government restrictions including persecution by government inspectors and heavy fines, as well as constraints on capital accumulation and business growth. He provides his own recommendations to alleviate these problems.

One fundamental question left unanswered is the size of the NSS. Unfortunately, there are no official data on the NSS, complete and disaggregated by components. Neither Ritter and Henken nor most Cuban authors provide such a figure (Torres estimates it as 27 percent of the labor force; p. 21). The only elaborated calculation in the four books is Feinberg’s, who states that “altogether, as many as 2 million enterprising Cubans—40 percent of total employment—and possibly even more can be counted within the private sector” and predicts that “in the next three to five years, total private employment could reach 45 to 50 percent of the active labor force” (Feinberg, 132, 139; emphasis added); this exceeds by 10 percentage points Torres’s middle-term estimate of 35 to 40 percent (24).

Feinberg overestimates the NSS’s size. First, an important semantic and substantive issue is that not all NSS participants are private, only most self-employed workers and their employees as well as small private farmers are. Usufruct farmers, NASCs, and other cooperatives’ members do not own their land or buildings; these belong to the state, which leases them to the workers. Second, several figures in Feinberg’s estimates are either questionable or not supported by specific sources; the main query is what he labels “other private activities (estimated),” such as full-time unregistered self-employment and partial self-employment done by state-sector employees, which add up to between 185,000 and 1,185,000, based on guesstimates (while it is true that some government employees work part-time as self-employed workers, it is impossible to know for how many hours, which makes it difficult to estimate average full days of work). Third is the inclusion of 353,000 members of credit and service cooperatives (CCS), because that number exceeds by 65 percent the total number of all co-op members in 2015, including agricultural production (UBPCs, Basic Units of Agricultural Production, and CPAs, Agricultural Production Co-ops), CCSs (Credit and Services Co-ops) and NASCs.10 Furthermore, many private and usufruct farmers are also members of CCSs, thus they are counted twice. Fourth, the category of “land lease farmers” (172,000) is confusing; on the one hand Feinberg does not specifically include usufruct farmers (312,296), and on the other hand the official data on land leasers (arrendatarios) is only 2,843.11 Fifth, employees of self-employed workers are counted since 2011 in the total number of the self-employed, mixed with owners, and we have shown that there is a double counting in the overall figure. In any case, the official statistics on the total NSS share in the employed labor force expanded from 17 percent in 2008, when Raúl officially became president, to 29 percent in 2015.12 In conclusion, there is no doubt that the NSS is important and growing, but certainly not as much as Feinberg estimates.

In summary, the most studied NSS group is the self-employed; NASCs are briefly discussed by Ritter and Henkel and in Piñeiro’s chapter in Zavala et al. Largely excluded from the discussion are usufruct farmers, and totally omitted is the selling/buying of private homes. The historical approach is followed most intensively by Ritter and Henken, although several Cuban authors provide summaries of the evolution in their respective topics. The preferred methodology is interviews or conversations combined with research. There is a consensus that the NSS (mostly self-employment) has been successful despite considerable obstacles. We lack a reliable estimate of the NSS’s size.

Missing in the four volumes is an evaluation of the NSS’s macroeconomic effects.13 Ritter and Henken refer to some results of self-employment, such as job creation, noting the nonfulfillment of the official target of dismissing more than one million unneeded state employees. None of the books discuss the impact of usufruct farming on agricultural output, where NASC members are still minute and their impact is even more difficult to assess. It is true that the scarcity of available data hinder the task, but still some estimation could have been done on the NSS’s effect on produce sales, fiscal revenue, and GDP.14

Feinberg and Ritter and Henken are the only authors who explore the future of the NSS. Feinberg provides three broad overall scenarios, which are thought-provoking but touch little on the NSS: (1) “inertia” with little change, without citing potential precedents and projecting self-employment to 750,000, 48 percent higher than the March 2016 official figure of 507,342; (2) “botched transition and decay,” the most pessimistic, similar to former states of the USSR, but with self-employment expanding to 1 million, twice its 2016 size, as some restraints are removed; and (3) “soft landing” in 2030, the most optimistic, under market socialism as in Vietnam, where self-employment really takes off and reaches 2 million employees and 40 percent of the labor force—this is somewhat confusing because he refers to the private sector and had previously predicted, for the entire NSS, 45 to 50 percent in 2019–2021 (203–222).

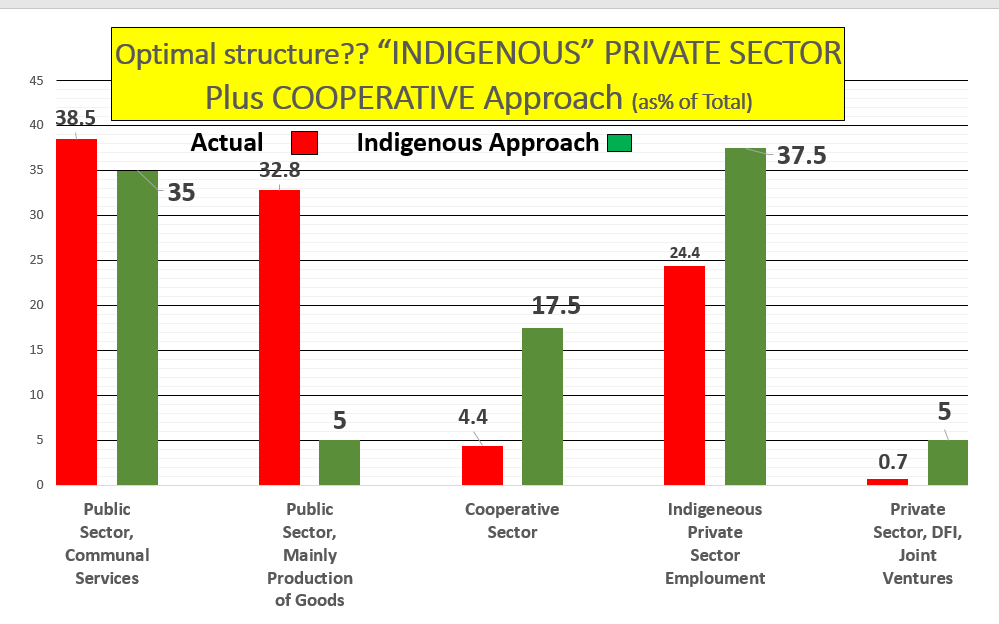

Ritter and Henken offer three possible alternative routes for the NSS, without predicting its size: (1) reversal to Fidel’s hostile approach, which they judge very improbable because it is totally unfeasible and discredited (“unlikely to be reversed” for Feinberg, 131); (2) stabilization of Raúl’s current (2014) and cautious reform package to self-employment and NASCs, which would remain in place for the rest of his presidency, but with a significant expansion of both and the potential of creating a “mixed cooperative market economy”; and (3) acceleration of the reform and rebalancing among public, private, and cooperative sectors, with medium and large private enterprises advancing at the expense of co-ops and smaller private enterprises; the viability of this scenario, they say, could be helped by a “serious relaxation of US policy toward Cuba” that could “encourage the Cuban government pro-market openings” (311).

Cuba is always unpredictable, and none of the three scenarios by the above authors completely fit the situation in August 31, 2016, when this review essay was finished. Ritter and Henken’s book was concluded in October 2014, thus this reviewer has the unfair advantage of almost two years that have brought significant changes, such as the evolution of US-Cuba rapprochement in 2014–2016 and the Seventh Congress of the Communist Party held in April 2016.15 In light of those events, their first and third alternatives are implausible, at least in the medium and long run; the second might be conceivable if the emphasis is placed on “stability” instead of significant expansion. By August 2016, however, rapprochement, rather than helping the reforms, appeared to have the opposite effect due to dread in the leadership caused by Obama’s visit and it effects, reflected in the results of the Seventh Party Congress. The number of self-employed workers peaked at 504,613 in May 2015, declined to 496,400 in December, and climbed again to 507,342 in March 2016, an increase of 0.7 percent in ten months, substantially lower that the expansion rate in 2014 and 2015 (14 and 3 percent, respectively). Furthermore, at the Congress, Raúl warned that although NSS forms are not antisocialist, “powerful external forces” try to “empower” them as agents of change, and could risk further “concentration of wealth and property” (the latter was not among the agreements of the Sixth Congress in 2011), making it necessary to impose “well-defined limits” on them.16 The Seventh Congress also recommended to halt the creation of new NASCs because of their deficiencies, and to concentrate on the existing ones instead.17 Finally, the only existing wholesale market was temporarily closed in May 2016. Feinberg’s book ended in early 2016, much later than Ritter and Henken’s, but his scenarios and predictions don’t correlate well with the facts explained above: “inertia” looks optimistic and even more so “decay”—both appear to be short- or middle-term effects—whereas the 2030 “soft landing” would require the drastic changes detailed by him, which are difficult to visualize now.

1 These basic principles of the reforms were set in the Sixth Communist Party Congress of 2011 and ratified in the Seventh Congress of 2016.

2 The pioneer book in the field is Jorge F. Pérez-López, Cuba’s Second Economy: From Behind the Scenes to Center Stage (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 1995).

3 Oficina Nacional de Estadística e Información (ONEI), Anuario Estadístico de Cuba 2015 (La Habana, 2016).

4 Carmelo Mesa-Lago, Market, Socialist, and Mixed Economies: Comparative Policy and Performance; Chile, Cuba, and Costa Rica (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2000).

5 ONEI, Anuario Estadístico de Cuba 2015.

6 A series of interviews conducted by five authors in 2014–2015, in a much wider part of Havana City, agreed with the predominance of men over women, the highest participation of middle-aged adults, and the important role of education, but found a prevalence of whites and a higher level of satisfaction. Carmelo Mesa-Lago et al., Voces de cambio en el sector no estatal cubano: Cuentapropistas, usufructuarios, socios de cooperativas y compraventa de viviendas (Madrid: Editorial Iberoamericana Vervuert, 2016).

7 ONEI, Anuario Estadístico de Cuba 2015.

8 Richard E. Feinberg, Soft Landing in Cuba? Emerging Entrepreneurs and Middle Classes (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 2013).

9 These cases are more varied than those discussed by Ritter and Henken, but the latter provided the most comprehensive and profound analysis of paladares.

10 ONEI, Anuario Estadístico de Cuba 2015.

11 ONEI, Anuario Estadístico de Cuba 2014 (La Habana, 2015).

12 Mesa-Lago et al., Voces de cambio en el sector no estatal cubano; ONEI, Anuario Estadístico de Cuba 2015.

13 Valdés notes in the prologue to Pérez Villanueva and Torres’s book the absence of a macroeconomic essay to place all NSS forms in the proper context.

14 The percentage of GDP generated only by self-employment has been estimated as 5 percent by Saira Pons, Tax Law Dilemmas for Self-Employed Workers (La Habana, CEEE), but by 12 percent by Torres (in Pérez Villanueva and Torres, p. 24), a significant gap. For an assessment of some NSS effects see Mesa-Lago et al., Voces de cambio en el sector no estatal cubano.

15 After this essay was finished, the guidelines (lineamientos) for 2016–2021 were published; a rapid browse indicates no significant changes from the guidelines of 2011.

16 Raúl Castro Ruz, “Informe central al Séptimo Congreso del Partido Comunista de Cuba,” Granma, April 17, 2016 (emphasis added), 1–3. Mauricio Murillo mentioned, as examples of the limits to be imposed, the establishment of limits on the number of hectares that somebody may have (“Intervención en el VII Período Ordinario de la Asamblea Nacional,” Granma, July 9, 2016).

17 Carmelo Mesa-Lago, “El lento avance de la reforma en Cuba,” Política Exterior 30, no. 171 (2016): 94–104.155

Preface

Preface