By Ramphis Castro, Founder, Mindchem

By Ramphis Castro, Founder, Mindchem

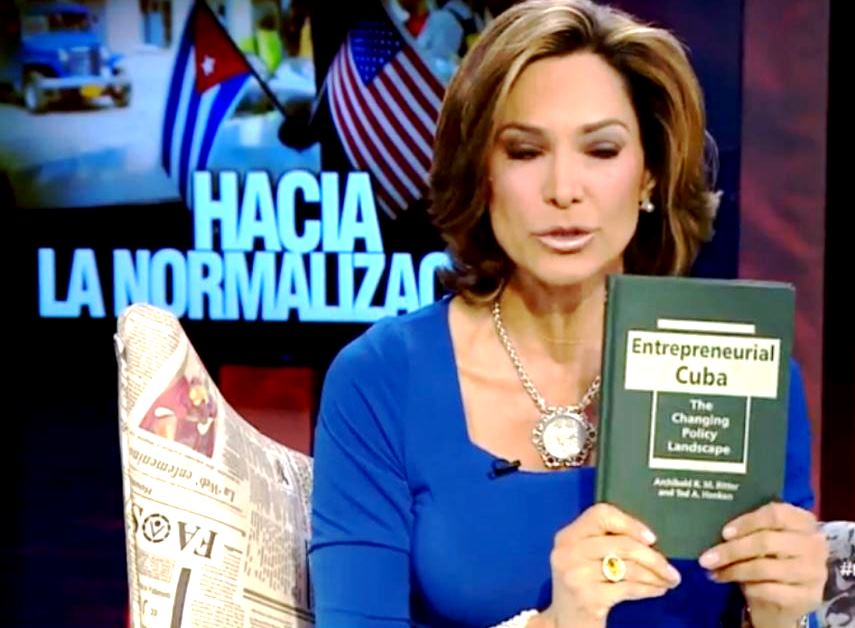

Original Here: Silicon Cuba?

When venture capitalists talk about Cuba as the next Promised Land, they note foremost the very real political hurdles that remain, both on the island and in the United States. The biggest obstacle, however, may be smartphones — the dearth of them.

Even as Cuba is a bright spot in the developing world for its top-notch health care and education systems, it remains in a technological dark age. Its communication systems, in particular, are almost as ancient as the Packards and Hudsons that putter around Havana. Mobile phone penetration (about one in 10 Cubans have one) is the lowest in Latin America, the country’s Internet is slow and government-censored, and owning a computer was illegal until eight years ago.

All of which makes it especially exciting to be a venture capitalist pondering the possibilities for funding companies in Cuba today and tomorrow. If VCs, particularly angel investors, can become involved soon, they will be getting in not at the proverbial ground floor but while the blueprints are being drafted.

Cuba, to be sure, has much to gain from the opening of its economy. For instance, it is one of the few places in the world where organic or non-GMO products, beloved by Americans, exclusively are grown. An export opportunity likely lies there. And then, of course, there is the Cuban cigar.

And certainly, the challenges for the first wave of early-stage VCs who hit the ground in Cuba are myriad. But we have made inroads before into early-stage economies: Iran, Yemen and Myanmar, to name a few.

Our fundamental role as VCs will be to support the creation of a new Cuban economy — one wanted by Cubans, not necessarily one desired by the U.S. or the outside world. Then we will back the local entrepreneurs who will build it.

A probable priority for Cuba: Telecom. Much of the island’s telephone connection with the rest of the world moves through an old undersea coaxial cable system. Banking networks and other infrastructure needed for e-commerce are just as antiquated.

The easing of sanctions announced by President Obama in recent months should make it more practicable for U.S. companies to export technology and consulting services to Cuba. There is the potential for leapfrog telecom networks, skipping over the wired and maybe even cellular network stages, going right to satellite technology.

The timing is excellent for VCs seeking partnerships in Cuba, as a new investment law, introduced in Cuba in March 2014, opens opportunities in agriculture, infrastructure, sugar, nickel mining, building renovation and real estate development.

Rodrigo Malmierca, minister for foreign trade and investment, believes Cuba needs to attract $2 billion to $2.5 billion in foreign direct investment per year to reach its economic growth target of 7 percent. To that end, in November 2014, the Cuban government appealed to international companies to invest more than $8 billion in 246 specified development projects. The 168-page Portfolio of Opportunities for Foreign Investment is available online and in English. “We have to provide incentives,” Malmierca said.

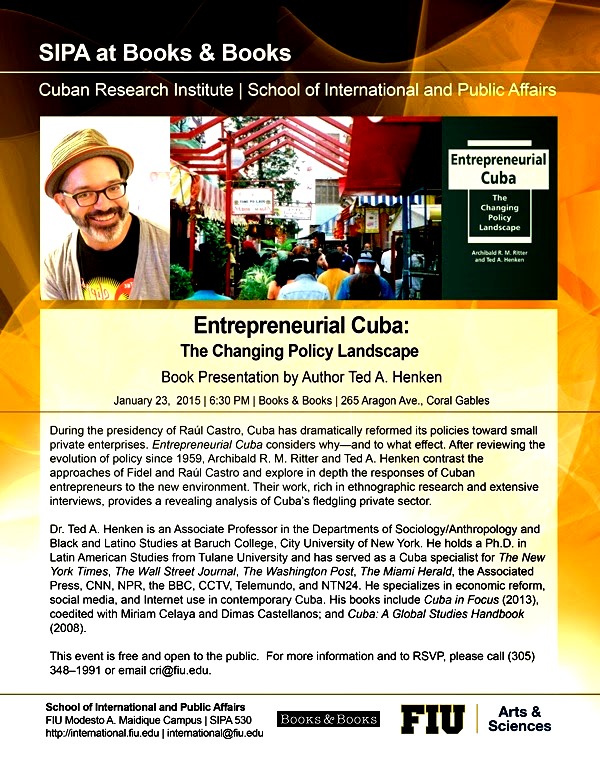

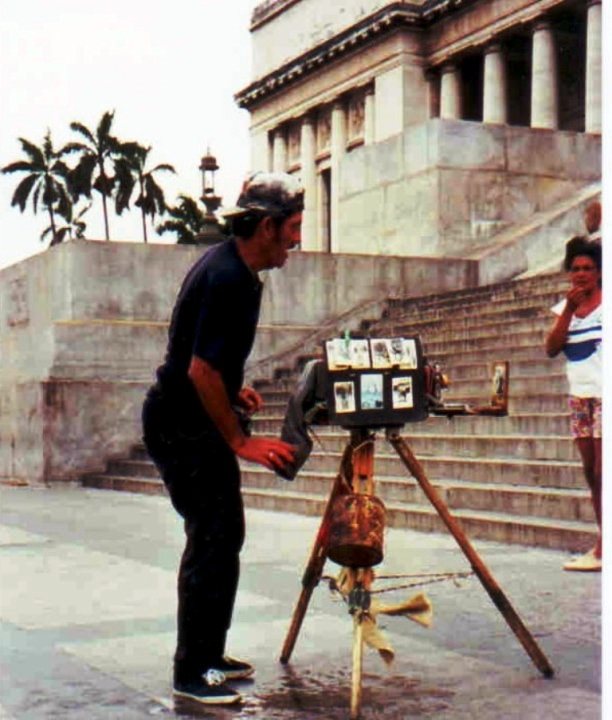

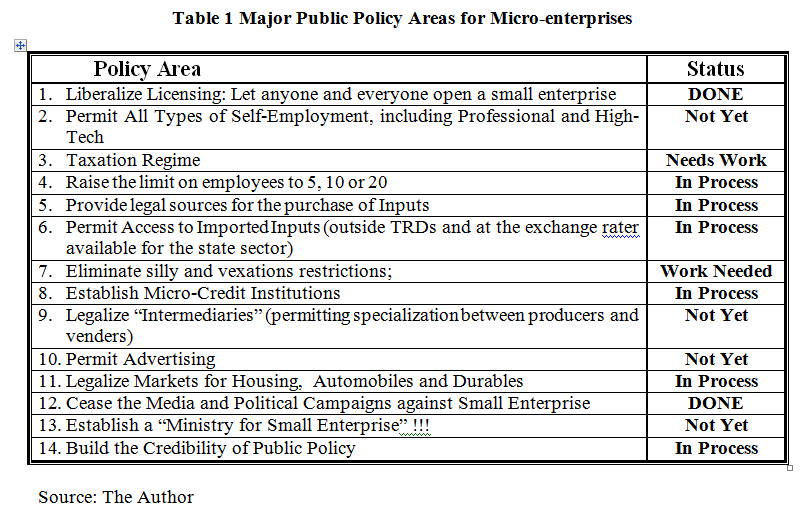

All this follows an initial effort four years ago by Cuba to make it easier, somewhat, to start a company, an initiative that hundreds of thousands of budding businessmen seized upon, taking their first steps into state-sanctioned capitalism.

Still, much more needs to be done — and faster — by both Cuba and the U.S. Congress for VC roots to take hold soon.

A recent Heritage Foundation report ranked only North Korea lower in labor freedom, respect for the rule of law and lack of corruption. Moreover, Cuba has repudiated or delayed debt payments to other nations and corporations; it also wants the U.S. to leave the Guantanamo Naval Base, which has proven to be problematic.

Meanwhile, in the U.S., resistance to normalization — although it’s lessening — remains problematic, as many Republicans, and especially Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida, the son of Cuban exiles, are unalterably opposed. Many Cuban exiles want reparations or the return of seized property and businesses, an unlikely scenario.

But the energetic, animated, conversations of the older generation Cuban exiles, often over a colada in Versailles or La Carreta restaurant in Miami, contrast with those of a new generation of Cuban Americans who want a different way forward and to play an active role in the rebuilding of their parents’ home country. At the same time, American nationals continue to become more curious about Cuba, its people, its music and business opportunities.

The rest of the world also has much to gain from Cuba’s expertise in medical-related fields; the country’s infant mortality rate is one of the lowest in the Western Hemisphere, and there’s a high-functioning universal health-care system.

Startups can catch fire in Cuba. And why shouldn’t they? Necessity is the mother of invention, and Cubans certainly have had a tough time in recent decades. The literacy rate, however, is high — higher than in the U.S. Cuba also has a strong culture of collaboration and support, two of the basic tools entrepreneurs use to meet challenges large and small.

Starting a business is human nature, too. The desire to prosper from trade has existed since antiquity. Holding back this instinct forever is impossible — it’s like stopping rain; eventually, it falls and things begin to grow. Such will be the case in Cuba.

Ramphis Castro — no relation to the Cuban leaders — lives in Puerto Rico. He is a Kauffman Fellow and founder of Mindchemy, a startup specializing in bringing technology entrepreneurship into the developing world. Reach him @jramphis.

The Past

The Future ! ?