The Castros, Cuba and America; On the road towards capitalism

Change is coming to Cuba at last. The United States could do far more to encourage it.

The Economist has produced one of its excellent surveys, this time focusing on Cuba.

Below are a set of hyperlinks to the various chapters of the Cuba Report. The chapter on the economy is presented following the Table of Contents.

Hyperlinked Table of Contents

Revolution in retreat; Revolution in retreat

Under Raúl Castro, Cuba has begun the journey towards capitalism. But it will take a decade and a big political battle to complete, writes Michael Reid

Inequality; The deal’s off

Inequalities are growing as the paternalistic state is becoming ever less affordable

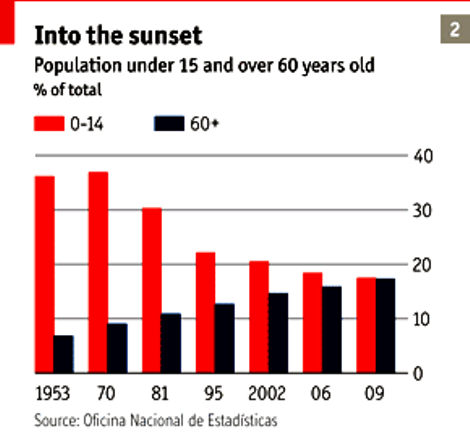

Population; Hasta la vista, baby

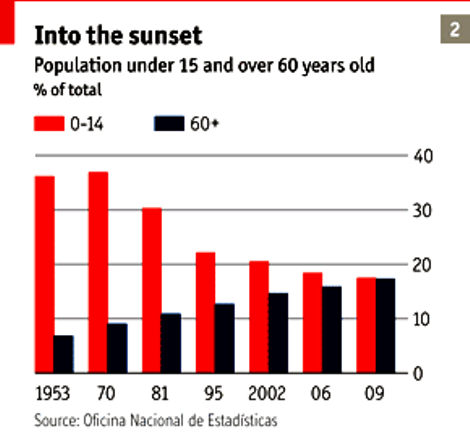

The population is shrinking, ageing—and emigrating

The economy: Edging towards capitalism

Why reforms are slow and difficult

Politics; Grandmother’s footsteps

With no sign of a Cuban spring, change will have to come from within the party

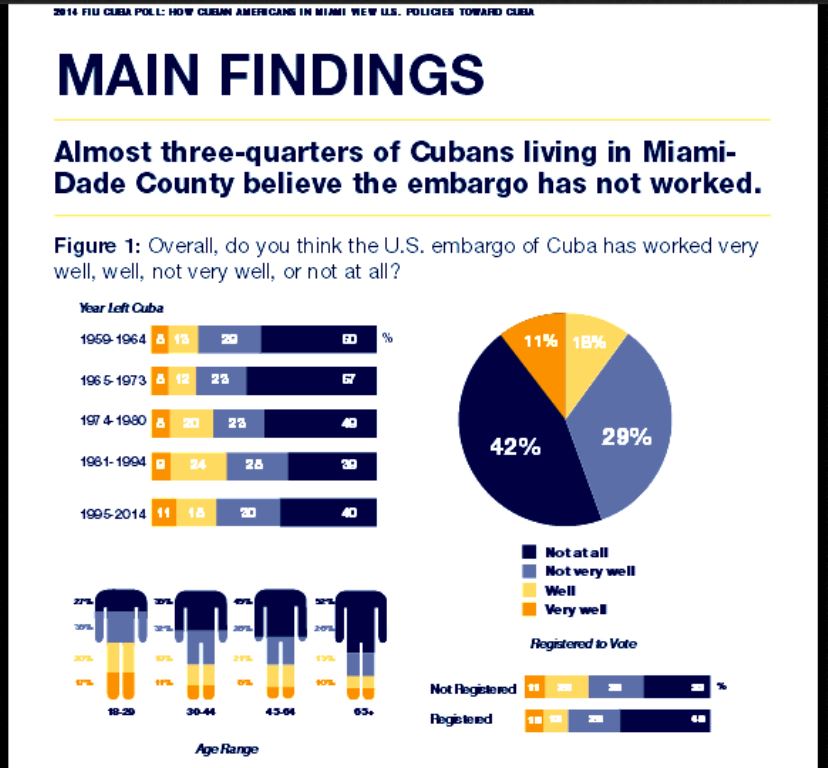

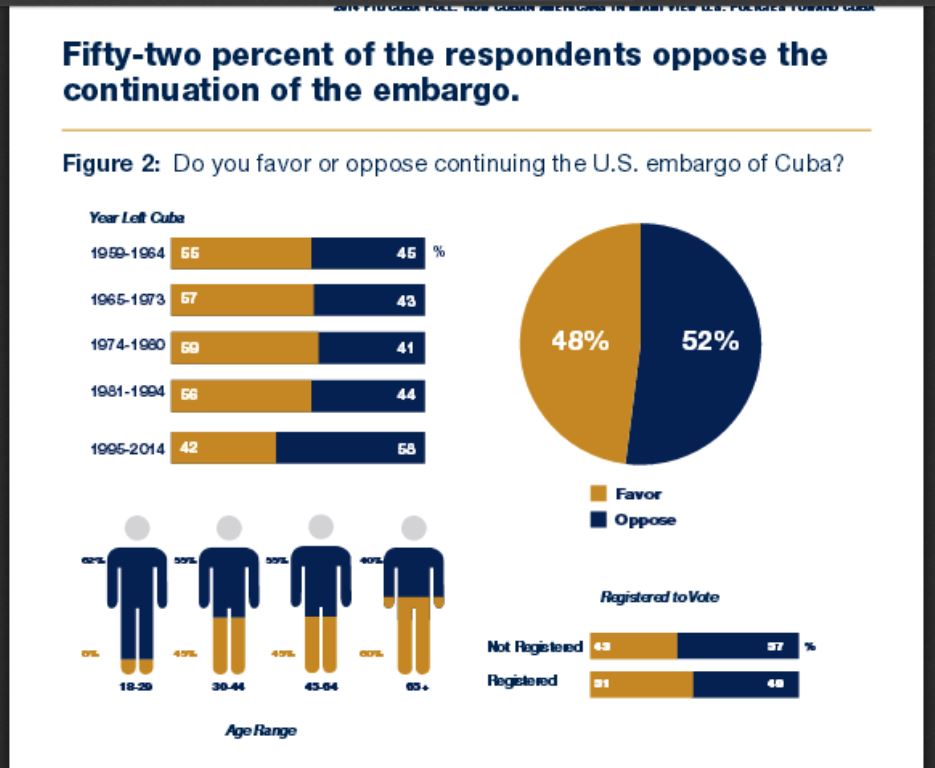

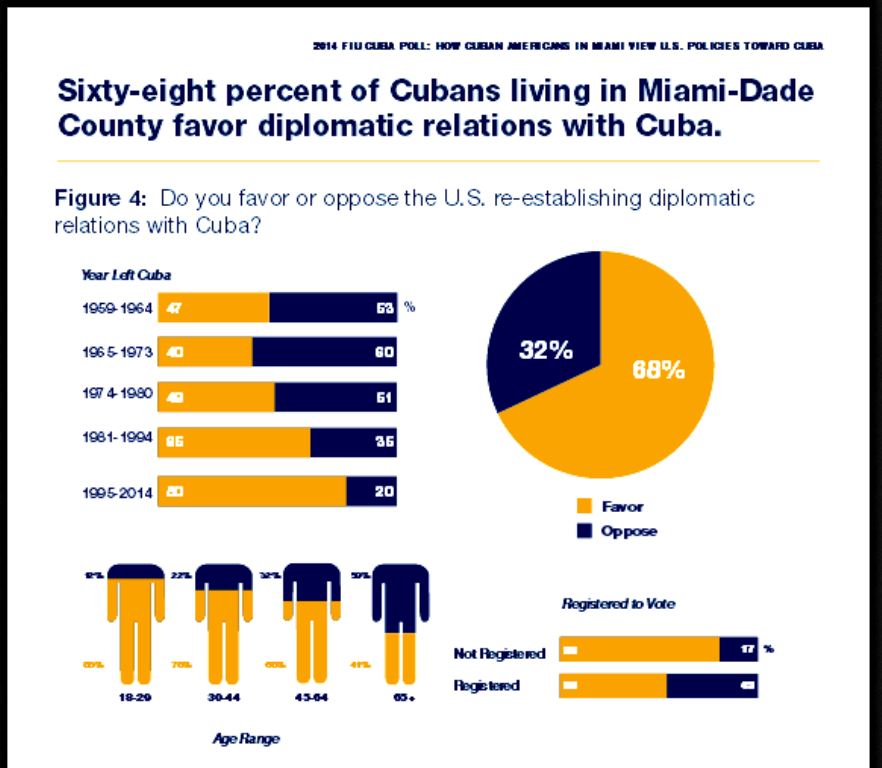

Cuban-Americans; The Miami mirror

Cubans on the other side of the water are slowly changing too

After the Castros; The biological factor

Who and what will follow Raúl?

The Economy: Edging towards capitalism

Why reforms are slow and difficult

GISELA NICOLAS AND two of her friends wanted to set up an events-catering company, but that is not one of the 181 activities on the approved list for those who work por cuenta propia (“on their own account”), so in May 2011 they opened a restaurant called La Galeria. With 50 covers, it is a fairly ambitious business by Havana standards. They have rented a large house in Vedado and hired a top chef and 13 other staff who are paid two to three times the average wage, plus tips. The customers are mainly foreign businesspeople and diplomats, Cuban artists and musicians and visiting Cuban-Americans.

“This opportunity means a lot to us,” says Ms Nicolas, who used to work for a Mexican marketing company. “But they haven’t created the conditions for a profitable business.” There are no wholesalers in Cuba, so all supplies come from state-owned supermarkets or from trips abroad. Reservations are taken on Ms Nicolas’s mobile phone. Advertising is banned, though classified ads in the phone book will soon be allowed.

Across Cuba small businesses are proliferating. Most are on a more modest scale than La Galeria. Fernando and Orlandis Suri, who are smallholders at El Cacahual, a hamlet south of Havana, can now legally sell their fat pineapples and papaya from a roadside stall, along with other produce. Orlandis plans to rent space on Havana’s seafront to sell fruit cocktails and juice. In Santa Clara, Mr Pérez’s wife, Yolanda, sells ice-cream from their home. Having paid 200 pesos for a licence and 87 pesos in social-security contributions, she earns enough “to buy salad”. The streets around Havana’s Parque Central heave with vendors hawking snacks and tourist trinkets. Many of them are teachers, accountants and doctors who have left their jobs for a more lucrative, if precarious, life in the private sector.

No reason to work

This cuentapropismo is only the most visible part of Raúl Castro’s reform plan. “The fundamental issue in Cuba is production,” says Omar Everleny, a reformist economist. “Prices are high and wages are low because we don’t produce enough.”

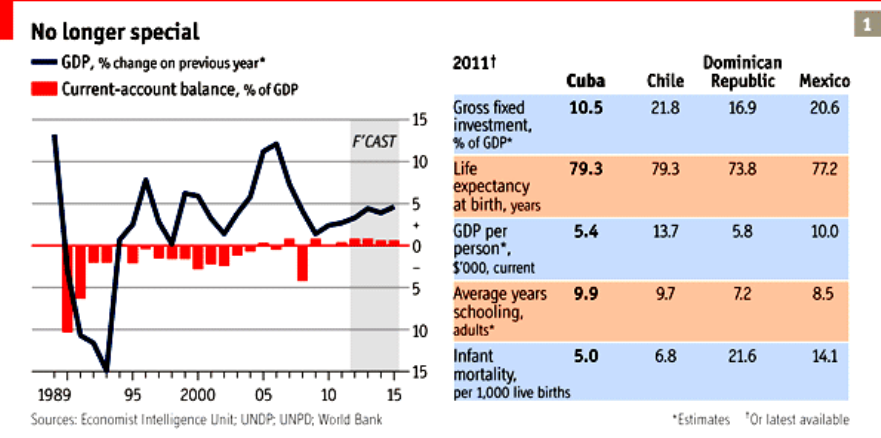

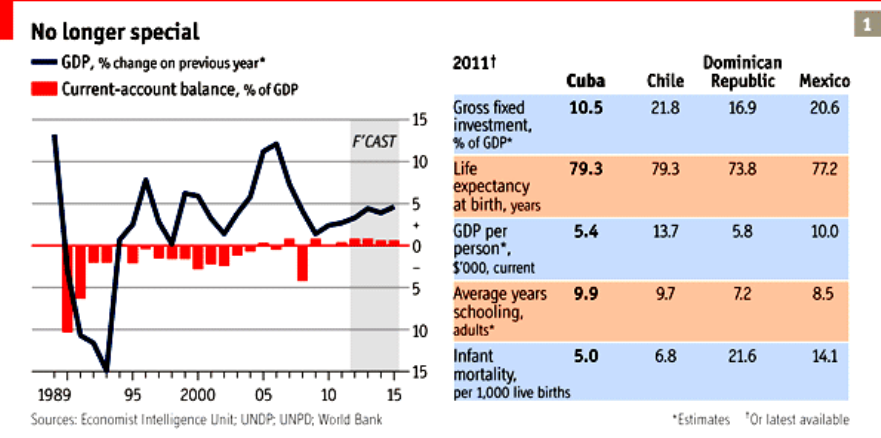

Cuban statistics are incomplete, inconsistent and often questionable. But in a lifetime’s detective work, Carmelo Mesa Lago at the University of Pittsburgh has calculated that output per head of 15 out of 22 main agricultural and industrial products was dramatically lower in 2007 than it had been in 1958. The biggest growth has come in oil and gas and in nickel mining, largely thanks to investment since the 1990s by Sherritt, a Canadian firm. But output per head of sugar, an iconic Cuban product, has dropped to an eighth of its level in 1958 and 1989. Capital investment has collapsed. Raúl Castro has repeatedly lamented that Cuba imported around 80% of the food it consumed between 2007 and 2009, at a cost of over $1.7 billion a year.

The American embargo is an irritant, but the economy’s central failing is that Fidel’s paternalist state did away with any incentive to work, or any sanction for not doing so. So most Cubans do not work very hard at their official jobs. People stand around chatting or conduct long telephone conversations with their mothers. They also routinely pilfer supplies from their workplace: that is what keeps the informal economy going.

The global financial crisis in 2007-08 also took its toll. Tourists stayed away, the oil price plunged, and with it Venezuelan aid. Hurricane damage meant more food imports, just when world food prices were rising and those of nickel, now Cuba’s main export, were plunging. All this coincided with the political infighting in which Mr Lage was ousted, during which “all financial and budgetary discipline was blown away”, according to a foreign businessman. Having repeatedly defaulted on its foreign debt, Cuba has little access to credit. Instead of devaluing the CUC, which would have pushed up inflation, in January 2009 the government seized about $1 billion in hard-currency balances held by state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and foreign joint ventures. It did not finish paying them back until December 2011.

The guidelines approved by the party congress contain measures to raise production and exports, cut import demand and make the state financially sustainable. This involves, first, turning over idle state land to private farmers; second, making the state more productive by transferring surplus workers to the private sector or to co-ops; and third, lifting some of the many prohibitions that restrict Cuban lives, and granting much more autonomy to the 3,700 SOEs.

The grip of the state on Cuban farming has been disastrous. State farms of various kinds hold 75% of Cuba’s 6.7m hectares of agricultural land. In 2007 some 45% of this was lying idle, much of it overrun by marabú, a tenacious weed. Cuba is the only country in Latin America where killing a cow is a crime (and eating beef a rare luxury). That has not stopped the cattle herd declining from 7m in 1967 to 4m in 2011.

In 2008 Raúl allowed private farmers and co-ops to lease idle state land for ten years. By December last year 1.4m hectares had been handed out. The government has now agreed to extend the lease-period to up to 25 years, allow farm buildings to be put up and pay for any improvements if the leases are not renewed.

Credit and technical assistance also remain scarce, says Armando Nova of CEEC. Farmers suffer in the grip of Acopio, the state marketing organisation. It is the monopoly supplier of inputs such as seeds, fertiliser and equipment and was the sole purchaser of the farms’ output, but its monopoly is being dented. Farmers can now sell surplus production of all but 17 basic crops themselves. Under a pilot programme in Artemisa and Mayabeque provinces, near Havana, new co-ops will take over many of Acopio’s functions.

The reformers want to see Acopio go. More surprisingly, so does Joaquín Infante Ugarte at the National Association of Economists and Accountants (ANEC): “It’s always been a disaster. We should put a bomb under it.” But in around 100 of Cuba’s 168 municipalities the economy is based on farming, so Acopio is a big source of power and perks for party hacks, and its future is the subject of an intense political battle. That makes farmers nervous. A year ago the 30 or so farmers in the Antonio Maceo co-op in Mayabeque leased extra land, got a loan and planted bananas, citrus and beans. The administrator says output is up, but “it will take time to see a real difference.” And with that he clammed up.

Official data suggest that output of many crops fell last year; the price of food rose by 20%. That may be partly because farmers are bypassing the official channels. Granma, the official—and only—daily newspaper, reported in January that a spontaneous, self-organised and regulated wholesale market in farm products has sprung up in Havana. That looks like the future.

Letting go is hard to do

Reducing the state’s share of the economy has been even more contested. Raúl originally said the government would lay off 500,000 workers by March 2011 and a total of 1.1m by 2014. That timetable has slipped by several years because the government has been reluctant to allow sufficiently attractive alternatives for workers to give up the security (and the pilfering opportunities) of a state job. But including voluntary lay-offs and plans to turn many state service jobs into co-ops (as has already happened with small barber’s shops, beauty parlours and a few taxi drivers), some 35-40% of the workforce of 4.1m should end up in the private sector by 2015, reckons Mr Everleny.

Raúl sees corruption as politically incendiary at a time of rising inequality

By October 2011, he says, some 338,000 people had requested a business licence, 60% of whom were not leaving state jobs, suggesting that they were simply legalising a previous informal activity. As happens to small businesses the world over, many fail in the first year. Few of the cuentapropistas have Ms Nicolas’s business experience. Many clearly find it hard to distinguish revenue from profit. ANEC is organising training courses. But the government has stalled an attempt by the Catholic church to set up an embryonic business school.

If cuentapropismo is not to be a recipe for poverty, the government will have to ease the rules. Mr Everleny wants to see private professional-service firms being established: architects, engineers, even doctors. Already the taxes levied on the new businesses have been cut, but they are still designed to produce “bonsai companies”, in the words of Oscar Espinosa Chepe, a dissident economist.

Lack of credit is another obstacle. Start-up capital for new businesses comes mainly from remittances. In a pilot scheme the government approved $3.6m in credits in January, nearly all for house improvements. As for deregulation, Raúl has taken some simple and popular steps, lifting bans on Cubans using tourist hotels and owning mobile phones and computers, and last year allowing them to buy and sell houses and cars.

But reforming SOEs is far more complicated. They have been told to introduce performance-related pay. The boldest step was last year’s abolition of the sugar ministry. In principle, SOEs that lose money will be merged or turned over to their workers as co-ops. But a planned bankruptcy law is still pending. So is the elimination of subsidies and the introduction of market pricing. Mr Ugarte of ANEC thinks much of this will happen this year, along with a new law to introduce corporate income tax.

The pace of change has picked up since the party congress set up a commission with 90 staff under Marino Murillo, a Politburo member and former economy minister, to push through the reforms, says Jorge Mario Sánchez at CEEC. “By 2015 there won’t be the socialist economy of the 1990s, nor the same society.” But there are several gaps.

For one, the government seems undecided what to do about foreign investment, a key element in the rapid growth in Vietnam and China. It has cancelled some of the joint ventures it had signed (often in haste) during the Special Period, and such new agreements as it is entering are almost exclusively with companies from Venezuela, China and Brazil. Odebrecht, a Brazilian conglomerate, has reached an agreement under which it will run a large sugar mill in Cienfuegos for ten years. Many foreign companies are keen to invest in Cuba but are put off by the government’s insistence on keeping a majority stake and its history of arbitrary policy change.

Officials worry that foreign investment brings corruption. Raúl has launched an anti-corruption drive with the creation of a powerful new auditor-general’s office. Several hundred Cuban officials, some very senior, have been jailed, as have three foreigners. Raúl rightly sees corruption as politically incendiary at a time of rising inequality. But he is tackling the symptoms rather than the cause. “People who were making $20 a month were negotiating contracts worth $10m,” says a foreign diplomat.

The guidelines involve only microeconomic reforms. Raúl’s macroeconomic recipe has so far been limited to austerity: he has managed to trim the fiscal and current-account deficits. The trickiest reform of all will be unifying the two currencies, by devaluing the CUC and revaluing the peso. It would help if Cuba were a member of the IMF and the World Bank and had access to international credit, but so far the government has shown no interest in joining. Mr Vidal of CEEC points out that for devaluation to provide a stimulus, rather than just generating inflation, the economy would have to be far more flexible. That will require a political battle.

THAW IN US RELATIONS RAISES EXPECTATIONS; Tentative signs of openness heighten hopes, but is the island ready to do business?

THAW IN US RELATIONS RAISES EXPECTATIONS; Tentative signs of openness heighten hopes, but is the island ready to do business?