II. Peter McKenna, THE FUTURE OF GITMO

Ottawa Citizen, May 15, 2015

Original here: Gitmo

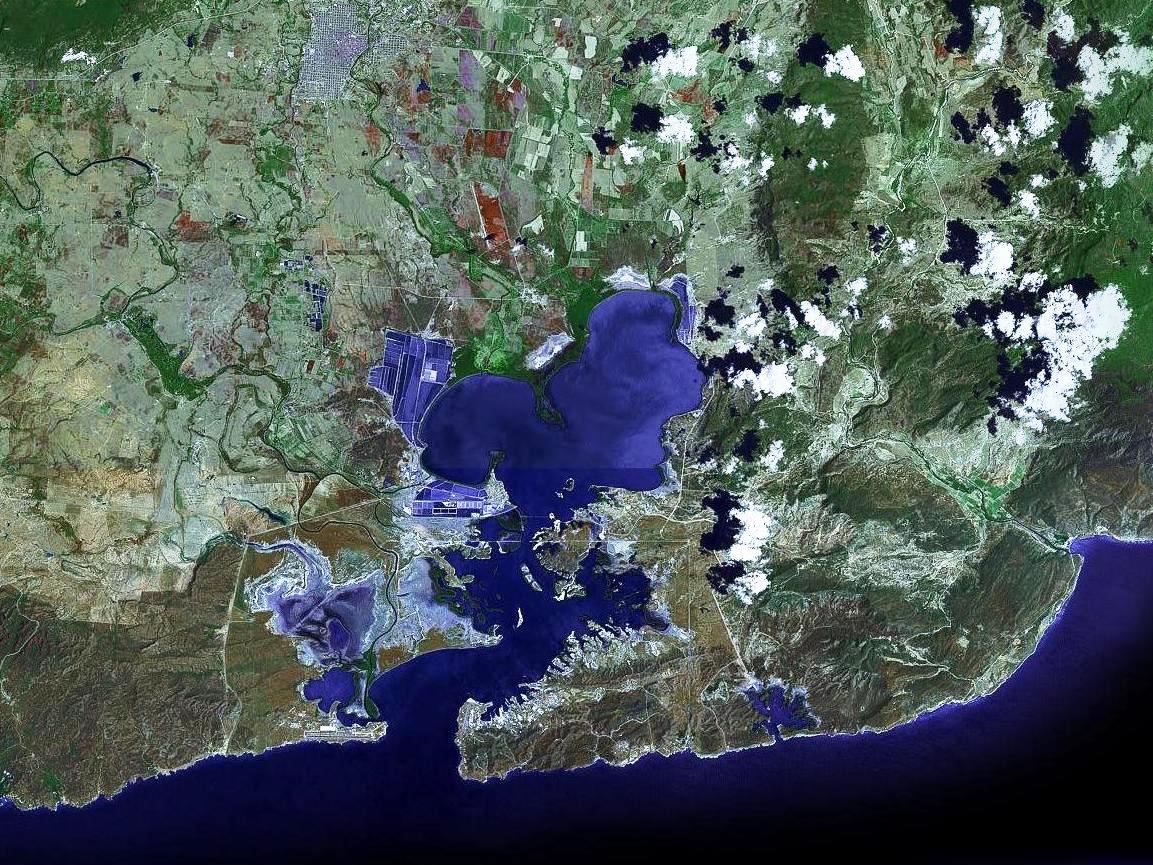

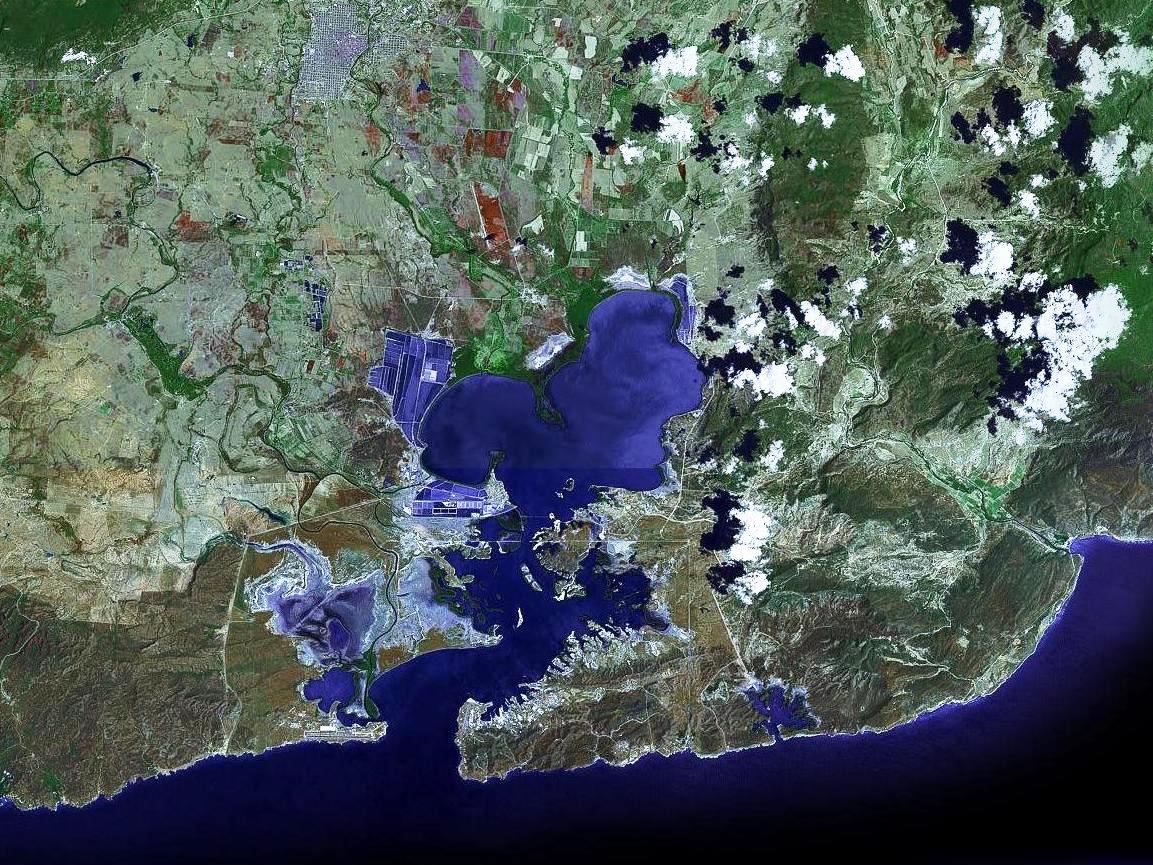

I’ve just returned from a visit to Guantanamo City and its outskirts. It is blistering hot in and around Guantanamo City, which surely doesn’t minimize the harsh prison conditions for the remaining 120 or so detainees at the U.S. naval facility in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. It is not clear what their fate will be if the U.S. base is eventually returned to the Cubans.

I’ve just returned from a visit to Guantanamo City and its outskirts. It is blistering hot in and around Guantanamo City, which surely doesn’t minimize the harsh prison conditions for the remaining 120 or so detainees at the U.S. naval facility in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. It is not clear what their fate will be if the U.S. base is eventually returned to the Cubans.

Taking up 117 square kilometres, which includes over 1,000 buildings and two airfields, it’s hard to miss in south-eastern Cuba. But will it prove to be a major stumbling block in the way of a normalized U.S.-Cuba relationship?

Interestingly, it is a self-contained U.S. military facility (or reservation) — replete with its own grocery store, movie theatre, church and golf course. It even has its own McDonald’s restaurant, the only one on the island.

The initial 1903 Cuban-American Treaty, which laid out the terms of the lease agreement, put the annual rental fee at 2,000 U.S. gold coins. The 1934 Lease Agreement set the current cost at US$4,085 and essentially gave the U.S. government a lease in perpetuity for the territory around Guantanamo Bay (for use as only a naval coaling station).

It is said in Cuba that the Castro brothers have either sent the lease cheques back to the Americans or left them un-cashed in a desk drawer somewhere. The Castro governments have always maintained that the lease component of the 1934 revised treaty is illegal.

Since the 1959 Cuban Revolution and the coming to power of Fidel Castro, Cuba has seen the U.S. base as “occupied territory” and has consistently demanded its return. To this day, Cuba’s political leadership views Guantanamo as a matter of national sovereignty and as rightful Cuban territory. And just about every Cuban whom I spoke with feels that same ways about the base, its tarnished colonial legacy, and its connection to Cuba’s identity.

Just in case, the Cubans have military bases (at least three) near and around the U.S. naval facility. There are other trenches, prickly cacti, fences and observation/guard posts to repel the Americans — to say nothing of the deadly minefield.

For the U.S. government, the domestic politics of relinquishing control of Guantanamo would suggest an American resistance to even broaching negotiations over its return. It also still has strategic importance in terms of the Caribbean (and China’s growing involvement in the region), value as a naval training facility, and as a means of keeping a watchful eye on Cuba. Notwithstanding a substantial financial operating cost, it will certainly not be easy for the U.S. to walk away from Guantanamo.

That explains why the Barack Obama White House said plainly in early 2015: “The president does believe that the prison at Guantanamo Bay should be closed down. But the naval base is not something that we believe should be closed.”

However, at a regional summit meeting in Costa Rica in late January, Cuban President Raul Castro was adamant about the transfer of Guantanamo back to Cuban hands. He noted that normal bilateral relations “will not be possible while the blockade still exists, while they don’t give back the territory illegally occupied by the Guantanamo naval base.”

Most Cubans know that the issue of Guantanamo is complicated and not likely to be resolved easily. But they are determined to get it back, which might make it a diplomatic deal-breaker.

Both sides may simply continue to agree to disagree about the base. Or, the prison could be closed down and the U.S. military presence further reduced (or wound down entirely over a set period of time). It is also possible that the stalemate over Guantanamo remains frozen in time — at least in the short to medium term — while an improvement in bilateral relations limps along.

One hopes that a normalization of U.S.-Cuban relations doesn’t get torpedoed by an antiquated lease agreement. But if Cuba and the United States are unable to come to a meeting of the minds on Guantanamo (e.g., essentially a complete transfer back to Cuba), it’s hard to see how a full-fledged rapprochement can take place.

Peter McKenna is professor and chair of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island in Charlottetown.

.

.

II. Nick Miroff, WHY THE US BASE AT CUBA’S GUANTANAMO BAY IS PROBABLY DOOMED

The Washington Post, May 18, 2015

Original here: Us Base at Guantanamo Probably Doomed

HAVANA — If the United States and Cuba restore diplomatic ties in the coming weeks, as anticipated, the two countries will still be a long way from anything resembling a “normal” relationship, Cuban President Raul Castro has said repeatedly. His list of grievances is lengthy. But this week Castro said it boils down to two big issues.

The first, of course, is the U.S. trade embargo. The other is the Guantanamo Bay Naval Station, the oldest overseas American Navy base in the world, which the United States has occupied for 116 years.

That one isn’t up for debate, the Obama administration says. But, one can only wonder, for how long?

Scholars and military experts say it’s difficult to see how United States can overhaul its relationship with Havana while hanging on to a big chunk of Cuban territory indefinitely, especially if relations warm significantly in a post-Castro era.

While there are plenty of examples in the world of disputed borders or contested islands, the 45-square-mile American enclave at Guantanamo is something of a global geopolitical anomaly. There is no other place in the world where the U.S. military forcefully occupies foreign land on an open-ended basis, against the wishes of its host nation.

“It’s probably inevitable that we’ll have to give it back to Cuba, but it would take a lot of diplomatic heavy-lifting,” said retired Adm. James Stavridis, a former Supreme Allied Commander of NATO and now dean of the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University.

Stavridis was head of the U.S. military’s Southern Command between 2006 and 2009, putting him in charge of the Guantanamo base, which he said remains a “strategic, and highly useful” U.S asset. “It’s hard to think of another place with the combination of a deep water port, decent airstrip and a lot of land,” Stavridis said.

The controversial American detention camp for global terrorism suspects is just one of the base’s conveniences. It is a logistical hub for the Navy’s Fourth Fleet, as well as counter-narcotics operations and disaster-relief efforts. It also functions as a detention center for north-bound migrants intercepted at sea. The base’s location on Cuba’s south coast allows the U.S. military to project power across the entire Caribbean basin. And it’s strategically located next to Haiti, a place that often needs U.S. help.

As a military installation, though, Guantanamo — Gitmo is its nickname — is no longer essential in a modern era of aircraft carriers, nuclear submarines and drones, Stavridis said. “You wouldn’t launch a large-scale military operation from there,” he explained, adding that many of the other uses Guantanamo provides could be fulfilled by existing U.S. military facilities in Puerto Rico or south Florida.

“I don’t think it’s irreplaceable,” Stavridis said.

U.S. warships sailed into Guantanamo Bay in 1898, and together with Cuban rebels, defeated the Spanish fleet. The Americans essentially never left, conditioning Cuban independence on constitutional provisions allowing the U.S. Navy to occupy the area “for the time required.” Rent was set at $2,000 a year, paid in gold.

A new lease increased the amount to $4,000 in 1934, according to this history of the base by scholar Paul Kramer. But there was no cut-off date for the Americans to leave.

The U.S. government still dutifully sends rent checks to the Cuban government, but the Castros don’t cash them. They don’t recognize the lease, and — like landlords in a rent-controlled Brooklyn apartment — want their tenants to leave. Fidel Castro is said to keep the checks piled up in his desk drawer, using them as a kind of political prop. It’s hard to imagine a more ready-made symbol of U.S. imperialism than a military base whose history is so wrapped up in late 19th-century attempts at American empire.

After Castro’s revolution, the United States had no intention of letting the base fall under communist control. At times of peak tensions during the Cold War, such as the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, the base’s fences became a front line for the Soviet-American standoff. Volleys of gunfire were occasionally exchanged between U.S. and Cuban troops. One such event was dramatized in the 1992 film “A Few Good Men,” in which an agitated Jack Nicholson memorably told Tom Cruise he wouldn’t be able to handle the pressures of living under constant threat at Guantanamo.

Castro shut off the water and electricity in 1964, and today the base is completely isolated from the rest of Cuba. Visitors say it resembles a small American city, with the island’s only McDonald’s franchise, as well as a Taco Bell, a Subway and other American chains. The divide from the rest of the island is lethally enforced by land mines, concertina wire and thickets of thorny cactus.

In recent years, President Barack Obama’s unsuccessful attempts to close the base’s prison camp have inspired several dream scenarios of a post-military future for the base. One would converted it to a research center and treatment facility for tropical diseases and epidemics. If returned to Cuban control, it could become a second campus of Cuba’s Latin American School of Medicine, where students from around the world get free medical training from the Cuban government.

Stavridis said a proposal along these lines to “internationalize” the base that retains its value as a logistical center for humanitarian relief would probably be an acceptable future within the Pentagon — at least in the long run. Other optimists say the base’s transformation could serve as an exercise in trust-building between Cuba and the United States as hostilities ease.

Such a move wouldn’t be without precedent. The U.S. reluctantly gave up the Panama Canal Zone, a place far more strategic to military operations and U.S. commercial interests than Guantanamo Bay. Panama converted the military installations into a “City of Knowledge,” a cluster of research labs and campus facilities in partnership with several U.S. universities.

Miroff is a Latin America correspondent for The Washington Post, roaming from the U.S.-Mexico borderlands to South America’s southern cone. He has been a staff writer since 2006.