Mario A. González-Corzo* Cuba Transition Project, Institute for Cuban and Cuban-American Studies, University of Miami, Issue 239, March 11, 2015

Washington’s “new course on Cuba” presents a new set of challenges, opportunities and new prospects for the Island’s emerging self-employed workers. There are several reasons for this:

1. Despite existing constraints and limitations, policy contradictions, and the predominance of bureaucratic economic coordination mechanisms and centralized planning, the expansion of self-employment is one of the principal elements of Cuba’s efforts to “update” its economic model.

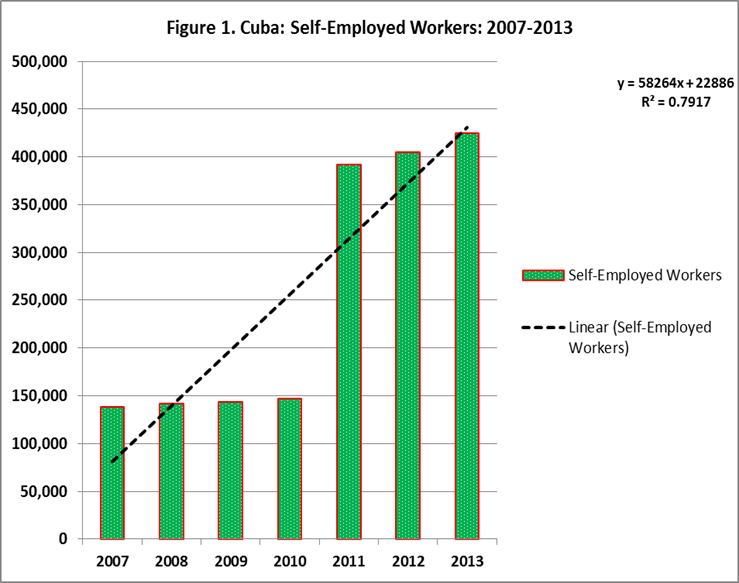

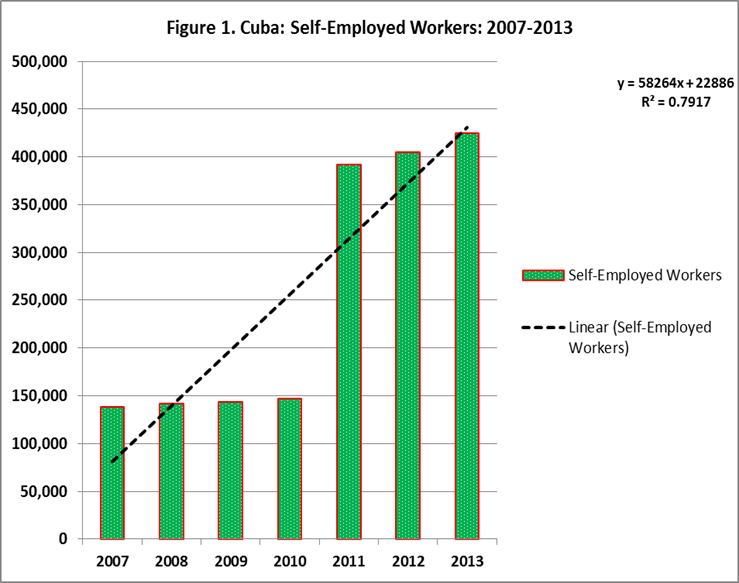

2.The implementation of a series of reform policy changes in Cuba since 2007, and particularly after 2010, have contributed to the rapid expansion of self-employment and its growing share of total employment (Figure 1).

Source: Oficina Nacional de Estadísticas e Información [ONEI], 2014; author’s calculations.

3. Despite facing strict State-imposed controls and limitations, self-employment has contributed to job creation, the provision of goods and services that were insufficiently produced by the State, and increases in the State’s tax revenues; it has also contributed to changes in attitudes, perceptions, and relationships between a growing segment of the Cuban population and the State, leaving a lasting “footprint” on the Cuban economy.

4. Since the limited liberalization of self-employment and the legalization of the U.S. dollar in 1993, self-employed workers have been among the principal recipients of remittances from abroad, particularly from the Cuban community in the United States, directly serving as one of the principal mechanisms to strengthen transnational ties between both countries.

While self-employment expanded significantly (206.6%), and its share of total employment increased notably during the 2007-2013 period, it has grown at a much slower rate, following the initial spurt experienced in 2011. This can be primarily attributed to existing restrictions on the types of self-employment activities that are currently authorized, excessive State regulation and intervention, the inexistence of input markets where self-employed workers and micro-entrepreneurs can obtain essential inputs at competitive prices in Cuban pesos (CUP), onerous taxation, and the remaining ambivalence of the State’s policies and attitudes towards the self-employed.

Cuba’s self-employed workers also have to contend with a dilapidated infrastructure, excessive bureaucratic constraints, insufficient sources of funding (excluding remittances), logistical difficulties do to the existence of primitive (quasi-formal) supply chains, government restrictions regarding the accumulation of capital (or concentration of wealth), and limited property rights. In addition, they lack access to mobile payment platforms, advanced (computerized) accounting and transactions (or sales) recording systems, and modern procurement and purchasing systems.

In terms of market segment concentration, it is worth noting that a notable share of self-employed workers is engaged in tourist-oriented activities such as food services (servicios de gastronomía), lodging or hospitality (alquileres), and transportation. Many of these depend on remittances from abroad as a primary source of working capital, and the majority of their client base consists of tourists and foreign visitors. Primarily catering to a limited (albeit affluent) market segment, rather than to a wider strata of the Cuban population, limits their market share and opportunities for growth and expansion.

Despite facing these challenges and limitations, the number self-employed workers in Cuba continues to expand (albeit at a slower pace in recent years), demonstrating the resilience of the entrepreneurial spirit that has historically characterized a significant portion of the Island’s population.

Given the growing importance of self-employment in the Cuban economy in recent years, the strong transnational linkages between a significant portion of self-employed workers and their friends and relatives in the United States, new U.S. policies towards Cuba are likely to impact this key sector of the Cuban economy in several ways:

- Continued expansion of self-employment activities, including new more value-added categories.

- Improved access to credit and equity capital to finance small-scale private business ventures.

- Opening to foreign investment, including partnerships with Cubans residing abroad.

- Future expansion of firm size, scope, and areas of operations.

- Greater share of total employment and contribution to Gross Domestic Product (GDP), tax payments, and social security system contributions.

- Adoption of modern point of sales (POS) systems, accounting systems, and inventory anagement systems to track sales and report business operations (and thereby improve the State’s ability to collect taxes from microenterprises and self-employed workers).

Despite all the potential (positive) effects of the new US policy approach with regards to self-employment, their real impact “on the front lines” depends on whether or not the Cuban government has the political will to implement deeper reform measures that will reduce the monopoly of the State, while permitting the expansion of the private sector by eliminating the “internal embargo.” On the economic front, this can be accomplished by lifting the internal restrictions, excessive regulations, onerous taxation, and bureaucratic limitations imposed by the State on the self-employed. On the political front, this process would require a radical shift in the State’s perceptions and attitudes towards the self-employed, recognizing Cuba’s emerging entrepreneurial class not only as a source of tax revenue for the State, but as primarily as a an engine of job creation, wealth formation, and the economic growth and development.

_________________________________________________

*Mario A. González-Corzo, Associate Professor, Department of Economics and Business, LEHMAN COLLEGE, City University of New York (CUNY), and is a Research Associate, Institute for Cuban and Cuban-American Studies (ICCAS), University of Miami

Preface

Preface